Authors: Grace Muzny, Mark Algee-Hewitt, Dan Jurafsky

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: computational linguistics, gender performativity, history of the novel, dialogue extraction, quote attribution

The Dialogic Turn and the Performance of Gender: the English Canon 1782-2011

Understanding how the spoken language is represented in novels over time, and how this relates to gender and other characteristics of the represented speaker and the author is a key question in the Digital Humanities. Previous work has explored such questions lexically, focusing for example on differences in word choice between male and female authors. Yet while such lexical stylistic approaches have been computationally sound (Argamon 2003, Olsen 2005, Yu 2014, Rybicki 2015), a purely lexical approach is known to have serious methodological dangers. Individual lexical items are highly conflated with topic, genre, author idiosyncrasies, and era, making it difficult to draw general conclusions, particularly over long time periods. An even greater problem is that this approach essentializes gender a priori (Bing & Bergvall 1996), neglecting how the complex interplay between an author and the characters they portray creates the performance of linguistically gendered writing.

We propose to draw from methods in social psychology (Newman 2008), network analysis (Schwartz 2013), and corpus linguistics (Biber 1991) to offer two innovations in the analysis of novels. The first is a new metric for characterizing dialogue, called dialogism, that references Bakhtin’s theories of novels and dialogue (1935). This measurement uses abstract grammatical features in the text to characterize the extent to which it is dialogic. By using categories like parts of speech, our method avoids the genre-specific and era-specific problems of individual words. Our second innovation is a computational analysis of the performance of gender within dialogue. We explore the relationship between the gender of the characters portrayed in novels and their language, which illuminates the performative aspects of gender.

Although we do not entirely escape the entrapments of gender as a defining authorship trait in our analysis, we do use it to develop deeper understanding of dialogue as a whole rather than simply a tool of reifying stereotypes. From our innovations, we propose to answer three important questions: 1) what is the composition of the dialogic landscape in fiction? 2) what characterizes dialogue linguistically? and 3) how is author gender and the gender performed by characters reflected in the language of dialogue?

1. Data and Dialogue Extraction

Using three corpora of novels from the beginning of the romantic period to the present day, we construct a corpus that contains 1,106 novels from 1782 until 2011. This corpus is largely composed of the standard English canon, with the pre-1900 portion drawn from Chadwyck-Healey, and therefore exhibits the bias present in canonical authorship, containing 851 male-authored novels and 255 female-authored novels.

We introduce and use a new dialogue extraction system to locate quoted text based on a series of rules and regular expressions.Then, using a number of high-precision patterns such as <QUOTE>-<PRONOUN>-<VERB>, we assign speaker gender to quotes associated with gender-disambiguating pronouns ( he, she, etc.) or proper names that can be reliably distinguished from gendered namelists. We evaluate our system on texts hand-labeled for quotes and speaker identity (Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (He 2013), Cooper’s The Spy, and Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby), resulting in average quote extraction of 94.5% of quotes at 95.4% precision and gender attribution of an average of 44.4% of the extracted quotes at 93.1% precision.

2. The Dialogic Landscape

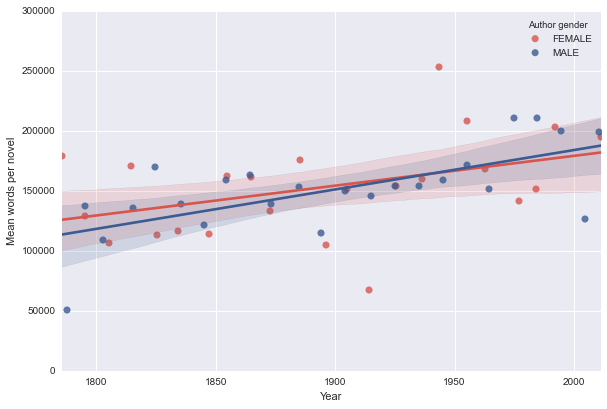

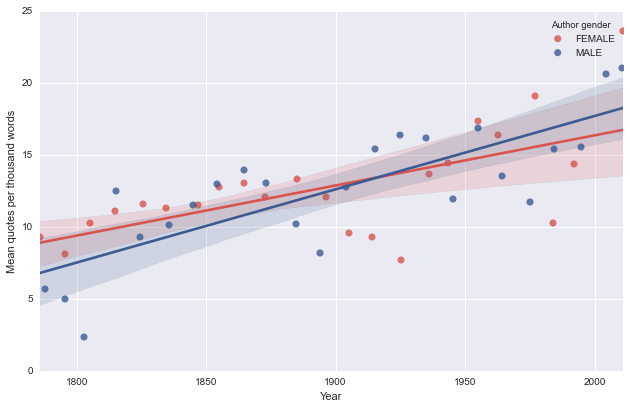

We first statistically evaluate the distributions of extracted dialogue to see whether novels have become more dialogue driven over time. Controlling for novel length (Figure 1), we measure mean quotes per thousand words per decade, finding a steady increase over time regardless of author gender (Figure 2). Overall, male authors add roughly 1 quote per 20 years (r2 =.80); female authors 1 quote every 30 years (r2 = .64).

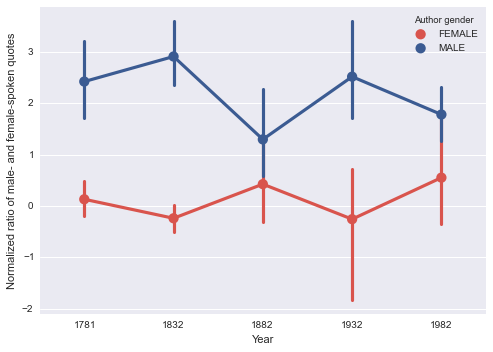

Next, we examine the relative attention that authors pay to characters and gender, using dialogue as our lens. From the extracted speaker-assigned quotes we calculate the proportion of male- to female-spoken dialogue per novel. This allows us to understand the gender of the characters portrayed in our texts and how this composition has changed over time.

We compute the mean of a normalized ratio of words spoken by male versus female characters per novel, bucketed by 50 year intervals (Figure 3). This ratio is normalized such that it forms a continuous spectrum centered at 0, with +1 signifying that male characters spoke twice as often; -1 that female characters did.

Here, we see that male authors tend to write male-spoken dialogue and female authors female-spoken dialogue, but that overall, female-authored dialogue tends to be close to balanced (mean = -.04) while male-authored dialogue is far from it (mean = 2.5). An interesting leap towards balanced portrayal happens among male authors at the beginning of the 20th century, influenced largely by authors such as Henry James, E.M. Forster, and Booth Tarkington.

3. Linguistic Characterization of Dialogue

To discover the underlying linguistic differences between narration and dialogue, we perform Multi-Dimensional Analysis (MDA) on the dialogue in our corpus, using a slightly modified set of Penn Treebank part-of-speech tags as distinguishing features. While it is not a classification algorithm, MDA isolates factors such that data with similar features are grouped together. These factors contain features that are positively or negatively correlated with one another. Effectively, even though no class labels are used, these factors reveal strong feature relationships for dialogic text.

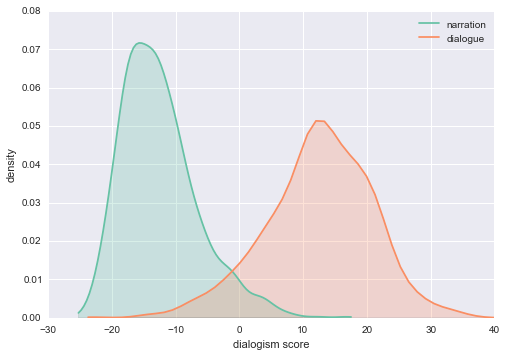

Based on this analysis we propose a new dialogue metric, dialogism, that is robust to lexical choice and transportable across corpora. The new metric is constructed from the ten factors (out of 16) with r2 > 0.5 when used to separate narration from dialogue and considers both positive indicators and negative indicators of dialogue, shown in Table 1. Figure 4 shows the high overall separation between narration and dialogue that our metric achieves (Kolmogorov-Smirnov value = 0.89).

| + | - |

| Present tense verbs, bare verbs, modals, 1st/2nd/”it” pronouns, Wh-pronouns, interjections, existential there, adverbs | past tense verbs, 3rd person pronouns, gerunds, particles, nominalizations, determiners, Wh-determiners, prepositions and subordinating conjunctions, adjectives |

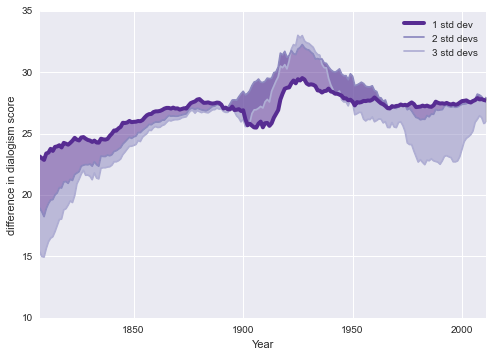

Examing dialogism over time, we find that the distance between narration and dialogue has increased since the 18th century, and that, as a whole, novels are becoming more dialogic. At the same time, visualizing the outlying data quantifies the effects that shifts in literary style, for instance, modernism in the early 20th century, had in terms of dialogism.

4. Gender in Dialogue: Performance and Authorship

We finally turn to the performative aspects of gender: how do authors perform gender through the speech of their gendered characters? Which authors most significantly differentiate their male and female characters through dialogue?

Using the same corpus, but subsampling to balance for speaker gender, we isolate author gender effects and use these results combined with the original data to isolate speaker gender effects. This analysis reveals that the differences between male- and female-authored dialogue cannot be accounted for solely based on either author gender or on the genders of the speakers they portray. Author gender accounts for 64% of the variation between male- and female-authored dialogue while other speaker gender effects account for 36%. However, because the standard deviation of this ratio is so high (23%), this is an indication that some authors are more heavily influenced by their own genders and some more by the characters they portray.

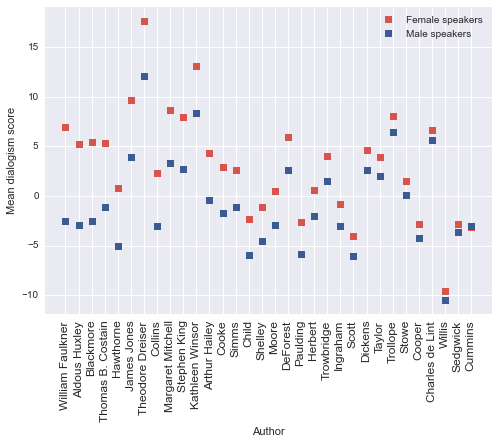

Digging deeper into the question of which authors are better than others at differentiating male and female characters through dialogue, we perform t-tests on the male- versus female-spoken quotes for each author. Shown in Figure 6 are the authors who differentiate their male and female characters through dialogue at p < .0005. Notably, while most authors portray female characters as more dialogic in speech, a small minority do the opposite (above, Maria Cummins), a trend that also holds at higher p thresholds.

5. Conclusion

The development of the novel is marked by an increased use of dialogue over time. This suggests that the deepening of characters was accompanied by, or may be an effect of, a shift of attention towards performative modes of characterization. Moreover, this transformation to a more dialoguedriven structure bears a gendered dimension, suggesting that the depiction of sociality by female novelists favored a more realistic gender balance than the predominately male social models favored in maleauthored texts. Our work suggests that the presence of any gendered language in the text may be contingent upon the mode of performance adopted by the author, regardless of gender, an observation supported by the variation in both dialogue cast composition and dialogism at the beginning of the 20th century, when a shift in literary style occurred. Further, the strict delineation of midnineteenth century sociality into the gendered public and private spheres, as represented by the novel, is itself a deeply gendered understanding of sociocultural codes more true of maleauthored texts than femaleauthored ones. The substantial effects that speaker gender has on dialogue indicates that perhaps not only are novels intrinsically dialogic, but that dialogue itself is intrinsically performative. Thus, the performative nature of a novel is itself deepened by the degree to which its’ author differentiates the characters through a gendered performance of dialogue.

6. Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-114747. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The authors thank their anonymous reviewers, the Stanford LitLab, and the Stanford NLP group for their helpful feedback.

- Argamon, S., et al. (2003). Gender, genre, and writing style in formal written texts. TEXT-THE HAGUE THEN AMSTERDAM THEN BERLIN, 23(3): 321-46.

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1935). Discourse in the novel. The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism And Theory 1900–2000, pp. 481-510.

- Biber, D. (1991). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge University Press.

- Bing, J. M. and Bergvall, V. L. (1996). The question of questions: Beyond binary thinking. Rethinking language and gender research: Theory and practice, 1: 30.

- He, H., Barbosa, D. and Kondrak, G.. (2013). Identification of Speakers in Novels. ACL, (1).

- Newman, M. L. et al. (2008). Gender differences in language use: An analysis of 14,000 text samples. Discourse Processes, 45(3): 211-36.

- Olsen, M. (2005). Écriture féminine: searching for an Indefinable practice?. Literary and linguistic computing.

- Rybicki, J. (2015). Vive la différence: Tracing the (Authorial) Gender Signal by Multivariate Analysis of Word Frequencies. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. fqv023.

- Schwartz, H. A., et al. (2013). "Personality, gender, and age in the language of social media: The open-vocabulary approach." PloS One 8(9): e73791.

- Yu, B. (2014). Language and gender in Congressional speech. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 29(1): 118-32.