Authors: Shih-Pei Chen, Zoe Hong, Dagmar Schäfer, Martina Siebert, Jorge Urzúa

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: tagging, visualization, geospatial analysis, data collection

Compiling a Database on Historical China from Local Records: The Local Gazetteers Project at MPIWG

This paper introduces a digital humanities project at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, MPIWG) that aims to unlock the treasure chest of local knowledge written in the genre of Chinese local gazetteers for computer assisted analyses.

In the past two decades, a great amount of historical documents have been digitized and put on the Web to enable easy access for scholars around the globe. In parallel, the amount of searchable full-text versions of historical texts has increased, which opens the possibility of text mining the contents for large scaled analyses. Many works in this direction have been proposed and got recognition, while they are also criticized for drawing conclusions from seemingly imprecise results due to the restriction that their algorithms have no knowledge about the meanings of the different pieces in a text (Jockers, 2013; Google Ngram Viewer; Chen et al., 2007).

An alternative approach is thus to first “teach” computers what each pieces of a text means before asking computers to run automatic analyses. Such “teaching” is done by tagging, or called markup. Many digital humanities projects have been using TEI, a standard for text encoding based on XML, to tag their research materials (TEI; Flanders).

In the Local Gazetteers Project, since the genre organizes knowledge in a very structural way, we are also using tagging to teach computers the meanings of texts in order to turn them into data tables to enable computer assisted analyses including GIS mapping. However, since the amount of texts is huge, we also propose a research data repository for scholars to collaborate in this project and to aggregate their results.

1. What are the Chinese Local Gazetteers?

The Chinese local gazetteers is a genre of texts that has been produced in China consistently from the 10 th century on to even today. Most of them are compiled by local officials as a major means to collect and aggregate historical, social, and geographical knowledge of an administrative region for governing purposes. There are at least 8,000 titles of pre-1949 local gazetteers still extant today. They cover almost every well-populated region in historical China.

Despite being compiled by different officials for different regions, the local gazetteers have developed a pretty consistent structure of “describing” local knowledge. Most gazetteers contain the following chapters: history, geography, local government, infrastructure (buildings, schools, temples, bridges), local products (grains, plants, animals, drugs, commodities), people (local officials and celebrities), and literature. The vast number, the longue durée, the width in geographical coverage, together with the extensive and consistent selection of topics have made the local gazetteers major sources for knowledge about regions for scholars from later periods. To date, several digitization projects on the local gazetteers have been conducted by either commercial vendors or public institutions, and thousands of titles have been made available in searchable full texts for scholarly access. 1

2. The Project’s Goal

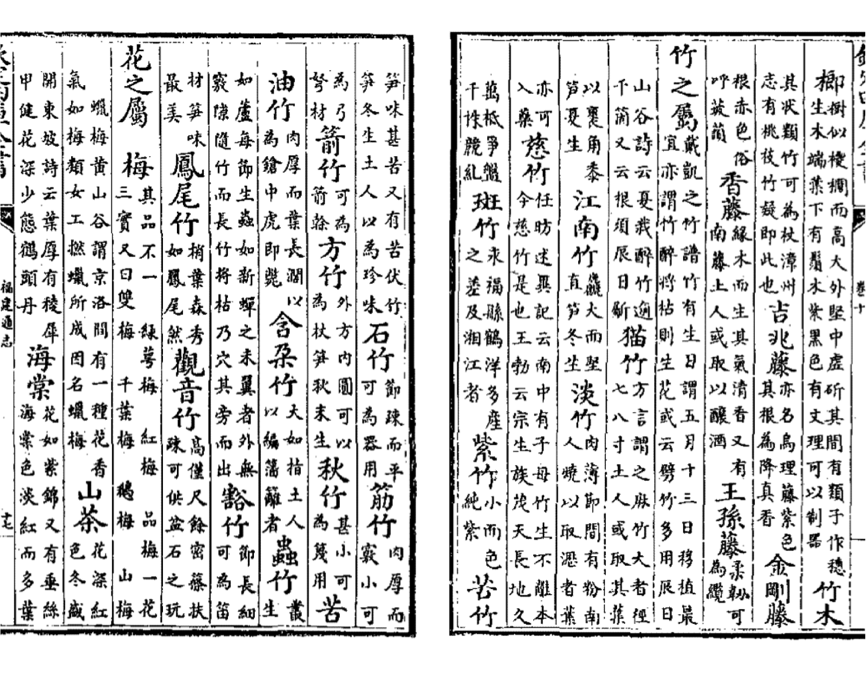

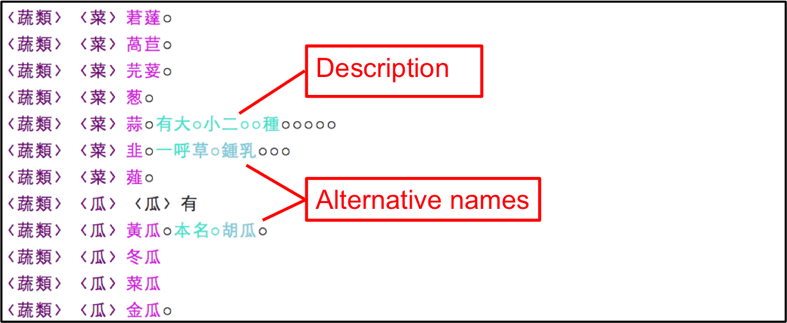

Local gazetteers are well studied, but the vast amount of information contained within also makes scholars struggled to study them analytically. We noticed that the local gazetteers often organize knowledge by listing the items: list of temples, lists of flora and fauna, lists of local officials, etc. (See Figure 1 for an example.) This characteristic makes the local gazetteers a database by nature.

The goal of this project is to transform this genre into a scholarly enhanced database in order to enable new forms of digital historical analyses. By turning texts (of lists of things) into data (tables), it will be much easier to aggregate the rich knowledge written in all the extant local gazetteers to compile a database for historical China on local knowledge across geographical regions and time periods. Research-oriented queries, visualization of query results, and further large scaled analyses will then be more easily realized with such a database.

3. Our approach

We have identified and developed a set of digital tools to help this process. They are: (1) an extraction interface that helps historians to tag and to transform digital texts and their built-in structures into data tables; (2) a research data repository where historians can share and publish their data collected via the extraction interface; (3) a set of digital analytical, visualization, and analysis tools that can be applied on the collected data for posing research questions.

3.1. I. An extraction interface for transforming digital texts into data

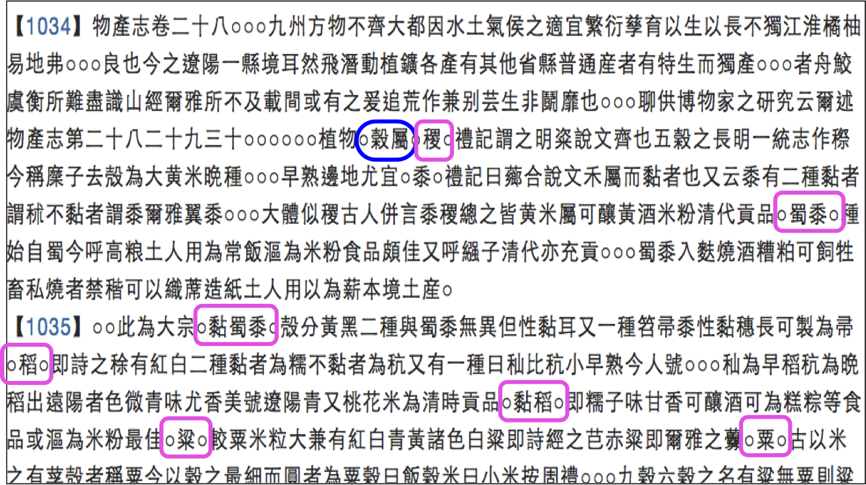

Due to the well-formatted organization of the local gazetteers, some scholars have tried to write computer programs to parse the digital texts in order to collect data for their own research (Mitchell, 2015; Chang, 2015). However, due to the fact that each of the local gazetteers has slightly different formats, it is difficult to write generic computer programs that can work on all the gazetteers. The China Biographical Database project (CBDB) tackled this problem by building an interactive user interface that allows scholars to describe observable writing patterns of the text in regular expressions (Wikipedia, 2015) – The Smart Regex Tool. The compiled regular expressions can be saved, run against other texts, and modified to fit slightly different writing patterns. CBDB used this interface and efficiently collected 250,000 records on local officials from 290 local gazetteers using only 420 man-hours (Pang et al., 2014).

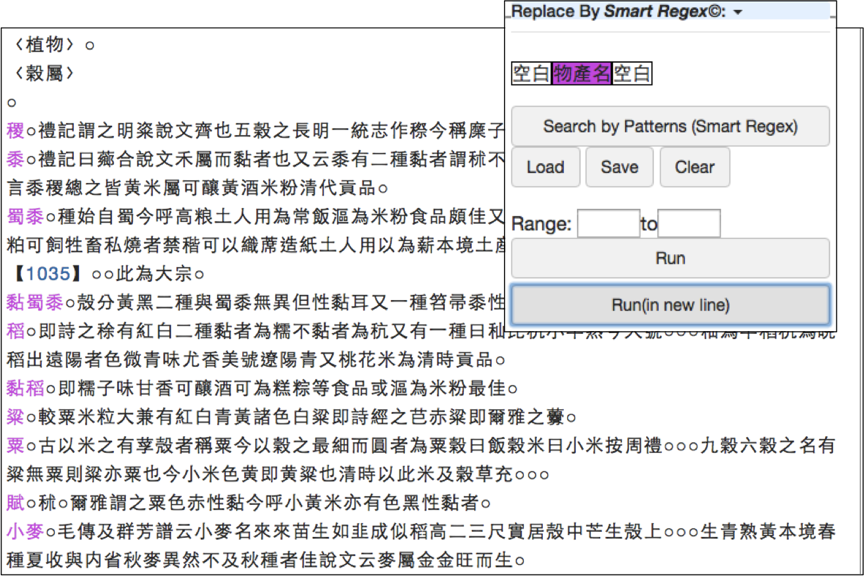

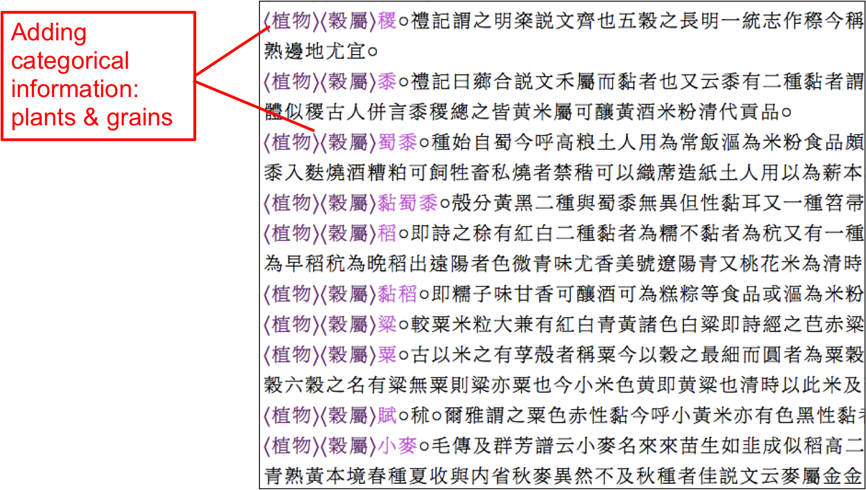

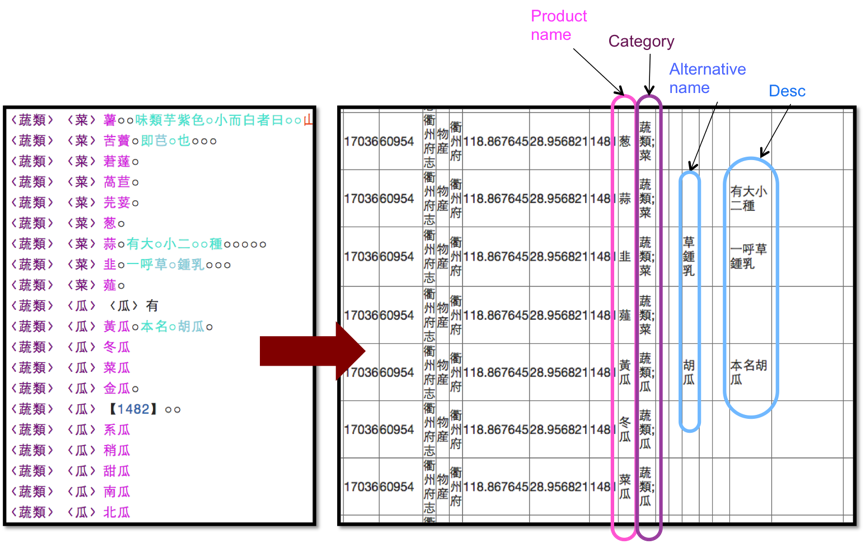

We inherited this interface from CBDB and further improved it so that scholars can define different tag sets and regular expressions to capture information relevant to topics they are interested in. Figure 2 to Figure 6 are the step-by-step screenshots of how we use this interface to tag a text on local product and to export the result into a table. The resulting table contains not only the names, categories, descriptions, alternative names, and usages of the products, but also the source gazetteer, the chapter name, and page number as well as geographical coordinates for mapping purpose.

3.2. II. Compiling a global database from local records: A research data repository

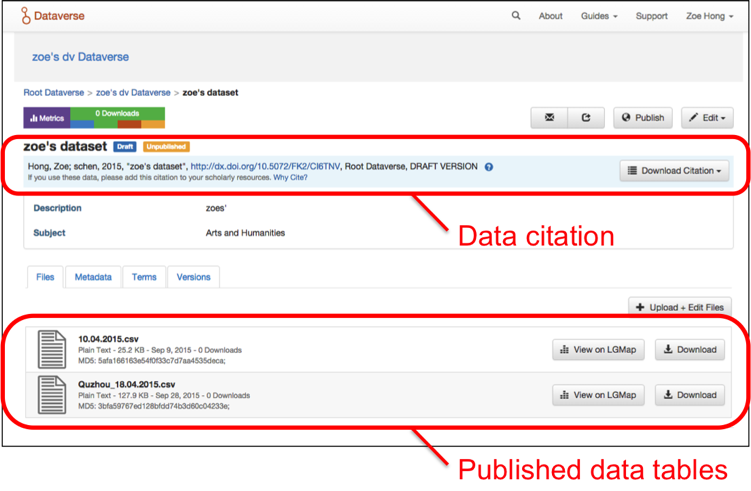

Our extraction interface provides a semi-automatic way of transforming texts into data tables. Nevertheless, compiling a global database through this interface will still take a lot of time. We envision it to be a collaborative work among scholars with different research interests and specialties, and we eagerly need to be a way to give credits to scholars who contribute the data in the academic world. We found that the philosophy behind the open source software Dataverse, developed by Institute for Quantitative Social Sciences at Harvard University with the philosophy of “dedicated to sharing, archiving, and citing research data” (IQSS, 2015), matches our needs and will allow our project to meet the open access policy of the Max Planck Society and the “Berlin declaration”. 2

After a text is tagged in our extraction interface, a user can publish the data to LGDataverse, a Dataverse instance we set up for this project. A citation link to the data along with the contributors will be shown on the LGDataverse page, urging any scholar who wishes to use the data to cite it in their publications (Figure 7).

We are still working on a way to aggregate the produced tables into one database in order to enable joint queries on records drawn from different gazetteers.

3.3. III. Computer assisted analyses on large scales

By transforming texts into data tables with predefined shared schema, it enables computers to easily process and analyze the data on large scales with better accuracy. We envision there can be multiple tools connected to our data, and scholars can choose which tools to use based on their research needs.

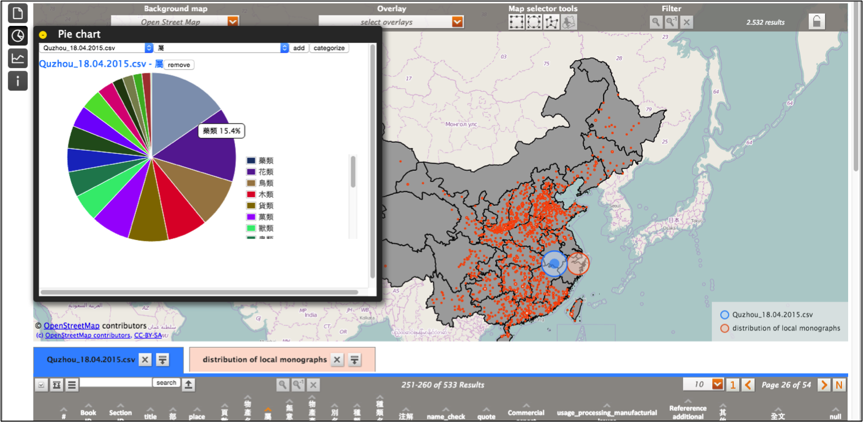

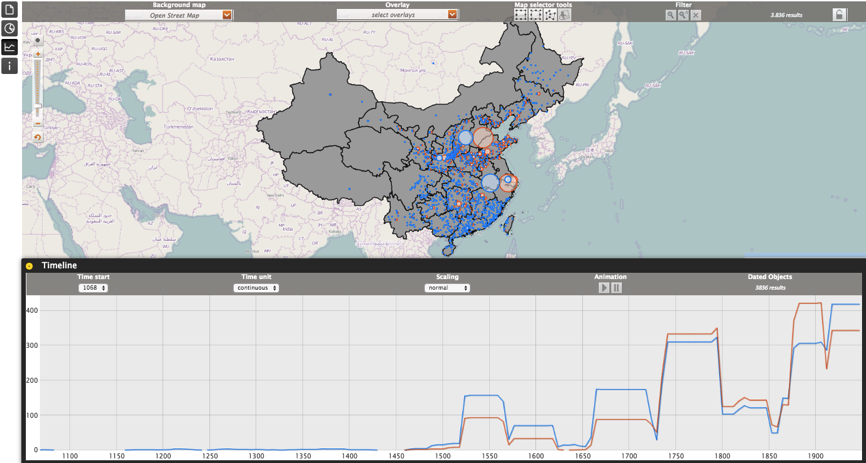

At the moment we are using the open source software PLATIN GeoBrowser (http://platin.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/) to create geospatial visualization for our data with one click away. PLATIN doesn’t just display the geospatial distribution of the data on a map but also provides an animated timeline and user-defined pie charts, which we found very helpful for historians for preliminary analysis (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

4. Concluding Remarks

This is an ongoing project. As a history of science study, we are collecting data from the chapter of local products in order to understand how local identities were constructed through the compilation of local products. In 2016, MPIWG will invite visiting scholars to use our digital tools to collect and analyze data of other topics from local gazetteers. This will also be a chance to further examine the model we proposed: from data collection from digital texts, aggregation of data in a research data repository, to digital tools for analysis and visualization.

- Chang, S. (2015). Data Extraction and Analysis: The Taxonomy of Fauna and Flora of Taiwan Local Gazetteers in the Qing Dynasty. Unpublished paper presentation at: Chinese Local Gazetteers workshop: Historical Methods and Computerized Data Collection and Analysis, Berlin, Germany.

- Chen, S.-P., Hsiang, J., Tu, H.-C. and Wu, M.-C. (2007). On Building a Full-Text Digital Library of Historical Documents. In Goh, D., Cao, T., Sølvberg, I. and Rasmussen, E. (eds.) Asian Digital Libraries. Looking Back 10 Years and Forging New Frontiers. Berlin: Springer, pp. 49-60.

- Flanders, J. (n.d.). Women Writers Project. Retrieved November 1, 2015, from http://www.wwp.northeastern.edu/

- Google Ngram Viewer. (n.d.). Retrieved November 1, 2015, from https://books.google.com/ngrams/

- Institute for Quantitative Social Science (IQSS), Harvard University. Dataverse Project [Online]. Available at: http://dataverse.org/ (Accessed: November 1, 2015).

- Jockers, M. L. (2013). Macroanalysis: Digital methods and literary history. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Mitchell, A. (2015). Encoding China’s Past: Computational Methods of Historical Analysis. In Unpublished paper presentation Chinese Local Gazetteers workshop: Historical Methods and Computerized Data Collection and Analysis, Berlin, Germany.

- Pang, W.H., Cheng, H. and Chen, S.-P. (2014). From Text to Data: Extracting Posting Data from Chinese Local Gazetteers. In the 5th International Conference of Digital Archives and Digital Humanities: Crossover and Transformation, Taipei: National Taiwan University, pp. 93-116.

- TEI: Text Encoding Initiative [Online]. Available at: http://www.tei-c.org/index.xml (accessed: November 1, 2015).

- Wikipedia. Regular expression [Online]. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regular_expression (accessed: November 1, 2015).

To name just a few of such digital local gazetteers project, there is first the Chinese Local Gazetteers Database (Zhongguo Fangzhii Ku) by a commercial vendor Erudition, second open access projects such as CTEXT.org with OCR-ed full texts of the gazetteers, and third national projects in China such as the Electronic Local Gazetteers by the Beijing National Library.

Please see the declaration at http://openaccess.mpg.de/Berliner-Erklaerung.