Authors: Adrian S. Wisnicki, Ashanka Kumari

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: manuscripts, spectral imaging, Victorian, empire, Africa

The Manuscripts of David Livingstone and New Frontiers for Spectral Imaging

1. Introduction

This presentation will focus on the results of the newest phase of the NEH-funded Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project (2010-present). This project seeks to apply spectral imaging and processing techniques to the study of some of the most damaged manuscripts produced by David Livingstone (1813-73), the famous Victorian traveler, abolitionist, geographer, and missionary. Our project asks whether spectral imaging can indeed restore erased or otherwise invisible portions of Livingstone’s writing. More recently, we also explore whether the technology can illuminate the specific circumstances of the production and preservation of Livingstone’s manuscripts, thereby better revealing the links between these manuscripts and the unique historical events that shaped the material dimensions of these manuscripts.

2. Methodology

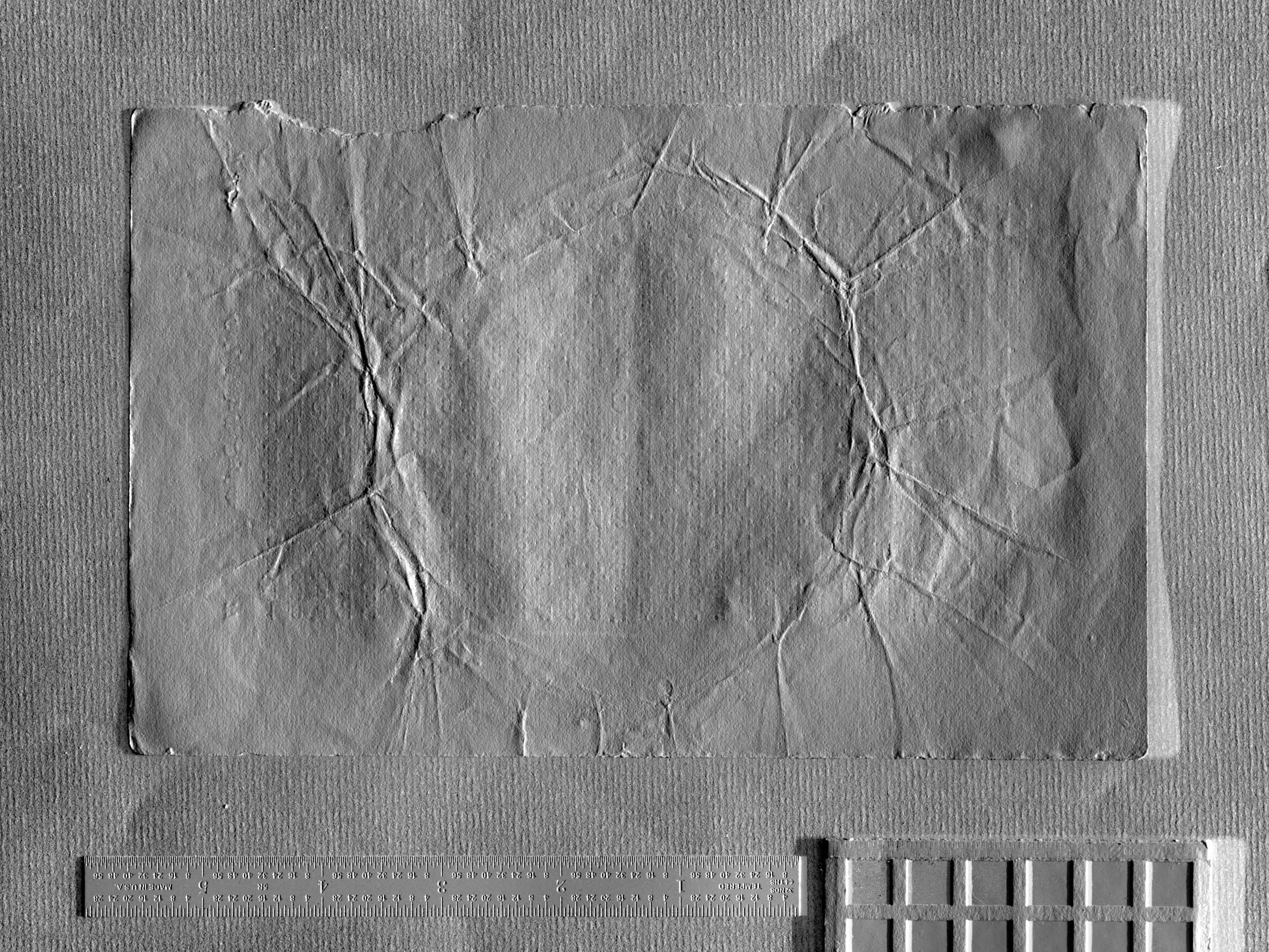

Spectral imaging, a technology beginning to make a significant impact in humanities research (see bibliography), relies on imaging an object, such as a manuscript, under multiple wavelengths of light, ranging from ultraviolet (UV) through the visible color spectrum to the near-infrared. A high-resolution monochromatic digital camera automatically photographs each illumination. Imaging scientists then manipulate this raw image data with computers by applying various processing algorithms with the goal of enhancing features of interest. Often these features are made more visible by creating pseudocolor (false-color) representations of the object that foreground or suppress other object elements.

Our previous research (Wisnicki 2011) applied spectral imaging to recover the text of a diary that Livingstone had written over newspaper pages and that had become illegible because, first, the considerable fading of Livingstone’s ink (which he had concocted out of a local African clothing dye) and, second, the continuing prominence of the black newsprint over which Livingstone wrote his text. Using a combination of new and established spectral image processing techniques, our team successfully suppressed the newsprint so that it no longer interfered with Livingstone’s text. By enhancing his writing so that it could be read easily, we were able to recover some 99% of Livingstone’s words (up from about 40% before) and, in turn, use this technique to reveal important new information about Livingstone’s strategies for representing his experiences in interacting with local populations in Central Africa.

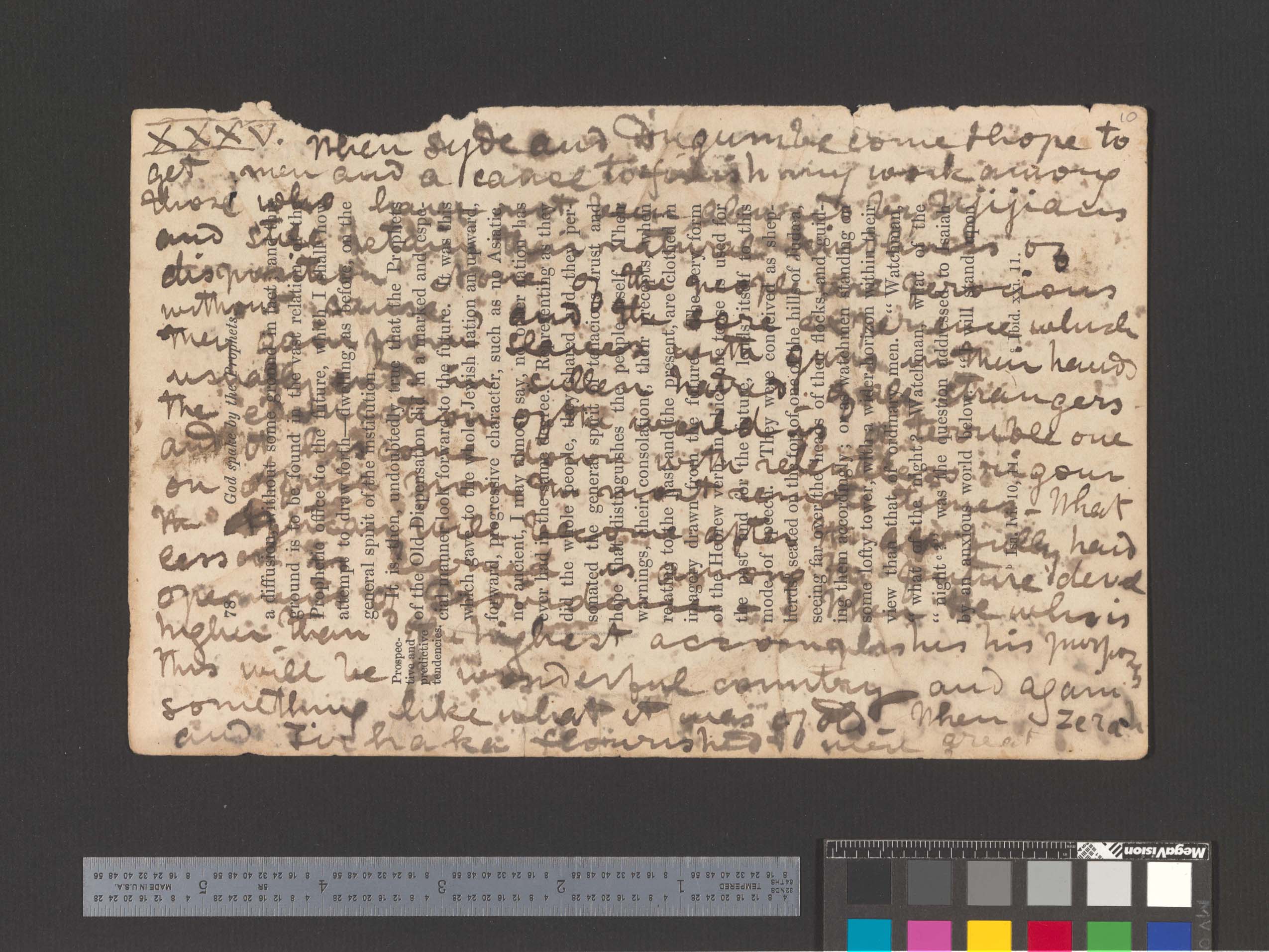

Our current project takes our previous research in a new direction to suggest that spectral imaging can illuminate the production and preservation history of Livingstone’s fragmentary 1870 Field Diary. With spectral imaging, we have enhanced or revealed material features of this diary, such as overwriting, staining, and page topography, that are often not visible or difficult to discern with the naked eye. Our results represent an important advance in the study of manuscripts with spectral imaging, particularly because previous related research has generally focused on using of spectral imaging for the recovery of faded texts or illegible palimpsests such as the Dead Sea Scrolls (Shor 2012) and the Archimedes Palimpsest (Netz and Noel 2007).

3. Historical and Scholarly Implications

Livingstone wrote the 1870 Field Diary in central Africa and carried it with him to his death in 1873 in what is now Zambia. Livingstone’s supporters then transported his manuscript (and his corpse) from the interior to the coast of Africa and back to Britain, where different repositories have since preserved the manuscript. The pages of the diary, therefore, bear the remnants of this complex history, from the changes and deletions that Livingstone made over time, to the marks left on the manuscript pages by the diverse local African environments through which the diary traveled, to the traces of modern curatorial methods used to preserve the diary’s pages.

Our efforts to study the material history of Livingstone’s diary with spectral imaging represent an important intervention in the field. Our work demonstrates new methods and frontiers for the use of spectral imaging in the humanities because it underscores that spectral imaging can do more than recover faded or invisible text. Spectral Imaging can provide crucial insights into the passage of a manuscript through time and into the relationship between a manuscript and the specific historical circumstances from which it emerged. By applying this technology to the 1870 Field Diary, we have gained key insights into the strategies by which Livingstone shaped his experiences and identity for public consumption and the impact of specific moments of handling in determining material features of the manuscript. These insights promise to enhance our understanding of Livingstone’s biography and the history of the many African cultures in which he worked.

Moreover, the spectral image processing techniques we have developed for the 1870 Field Diary can now be applied to study other manuscripts with notable textual and material features or, indeed, other cultural objects such as paintings and sculptures whose surfaces retain their material history and bear the marks of the many people and events that have come to shape the objects we encounter today. Our project is helping us distinguish such marks, but, in our case, the project also sets the stage for future research in which we might use the spectral signatures of specific marks as a portal to defining tangible aspects of nineteenth-century African environments from which Livingstone’s manuscripts emerged and through which these manuscript circulated.

- Chabries D. M., Booras S. W. and Bearman G. H. (2003). Imaging the past: recent applications of multispectral imaging technology to deciphering manuscripts, Antiquity,77(296): 359–72.

- Easton R. L. Jr., Knox K. T., Christens-Barry W. A., Boydston K., Toth M. B., Emery D. and Noel W. (2010). Standardized system for multispectral imaging of palimpsests, Proceedings of SPIE 7531, Computer Vision and Image Analysis of Art. 75310D.111, San Jose, California.

- Goltz D. M., Cloutis E, Norman L. and Attas M. (2007). Enhancement of faint text using visible (420-720 nm) multispectral imaging, Restaurator, pp. 11–28.

- Joo Kim S., Deng F. and Brown M. S. (2011). Visual enhancement of old documents with hyperspectral imaging, Pattern Recognition, 44(7): 1461–69.

- MacDonald L. W., Giacometti A., Campagnolo A., Robson S., Weyrich T., Terras M. and Gibson A. (2013). Multispectral imaging of degraded parchment, Proceedings of Computational Color Imaging, 4th International Workshop, CCIW 2013, Chiba, Japan, 3-5 March 2013.

- Marengo E., Manfredi M., Zerbinati O., Robotti E., Mazzucco E., Gosetti F., Bearman G., France F. and Shor P. (2011). Development of a technique based on multi-spectral imaging for monitoring the conservation of cultural heritage objects, Analytica Chimica Acta, 706(2): 229–37.

- Netz R. and Noel W. (2007). The Archimedes Codex: How A Medieval Prayer Book Is Revealing The True Genius of Antiquity’s Greatest Scientist. London: Da Capo Press.

- Shor, P. (2012). The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library. Israel Antiquities Authority. Retrieved from http://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/home.

- Walters Art Museum. (2008). The Archimedes Palimpsest data set. Baltimore: Walters Art Museum. Retrieved from http://www.archimedespalimpsest.org/.

- Wisnicki, A. S. (2011). Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary: a multispectral critical edition. Beta edition; first edition; corrections. Los Angeles: UCLA Digital Library. Retrieved from http://livingstone.library.ucla.edu/1871diary/index.htm.