Authors: Yu Fujimoto, Yasuhiko Horiuchi

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: Work-Oriented Approach, Information Standard, Digital Archive, ISO 191XX series

Standardized Digital workflow for Archiving Local Knowledge

1. Preface

The declining birth rate and resulting increase in the proportion of the elderly are serious issues for contemporary Japan. The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research reported that the 2010 Japanese population of about 128,057,000 is expected to decline to about 86,737,000 in 2060 with depopulation accelerating most acutely in local regions (The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2014). Currently, in 7,878 villages in Japan, over half of the population is over the age of 65. From this figure, it is predicted that 2,500 villages will vanish in the next 10 to 30 years (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 2014; Masuda, 2014). Given this situation, the preservation of local knowledge is essential and standardized digital archiving methods are required.

In contrast to national treasures, digital archiving for local cultural properties is limited in various respects. Digitizing devices should be versatile because the kind of materials buried is unknown at the onset of the survey. Budgets are therefore limited because most people in possession of such items do not have sufficient financial background. Therefore, the methods for archiving local items and knowledge should be as low-cost as possible. In addition to these problems, a standardized digital archiving workflow and information management rules are required to perform distributed autonomous digital archiving activities. Formulating digital archiving rules that are both open and standardized is also essential in terms of the Long Term Preservation issue (Lorie, R.A., 2001).

Responding to these issues, this paper will propose a low-cost digitizing workflow using an Mirror-less Interchangeable Lens Camera (MILC) and the information standard for local memories and knowledge with the concept of a Work-Oriented Approach (WOA) (Fujimoto 2011). The proposed methods have already been used in two different types of experimental projects and the results will also be summarized in this paper.

2. The digital archiving workflow

The digital camera is excellent in terms of saving space, versatility, speed of digitizing and later correction, and is therefore the ideal device for basic digital archiving. In particular, the Mirror-less Interchangeable Lens Camera (MILC) has a rich choice of lenses, and is lighter and therefore preferable to than the general Digital Single Lens Reflex camera (DSLR).

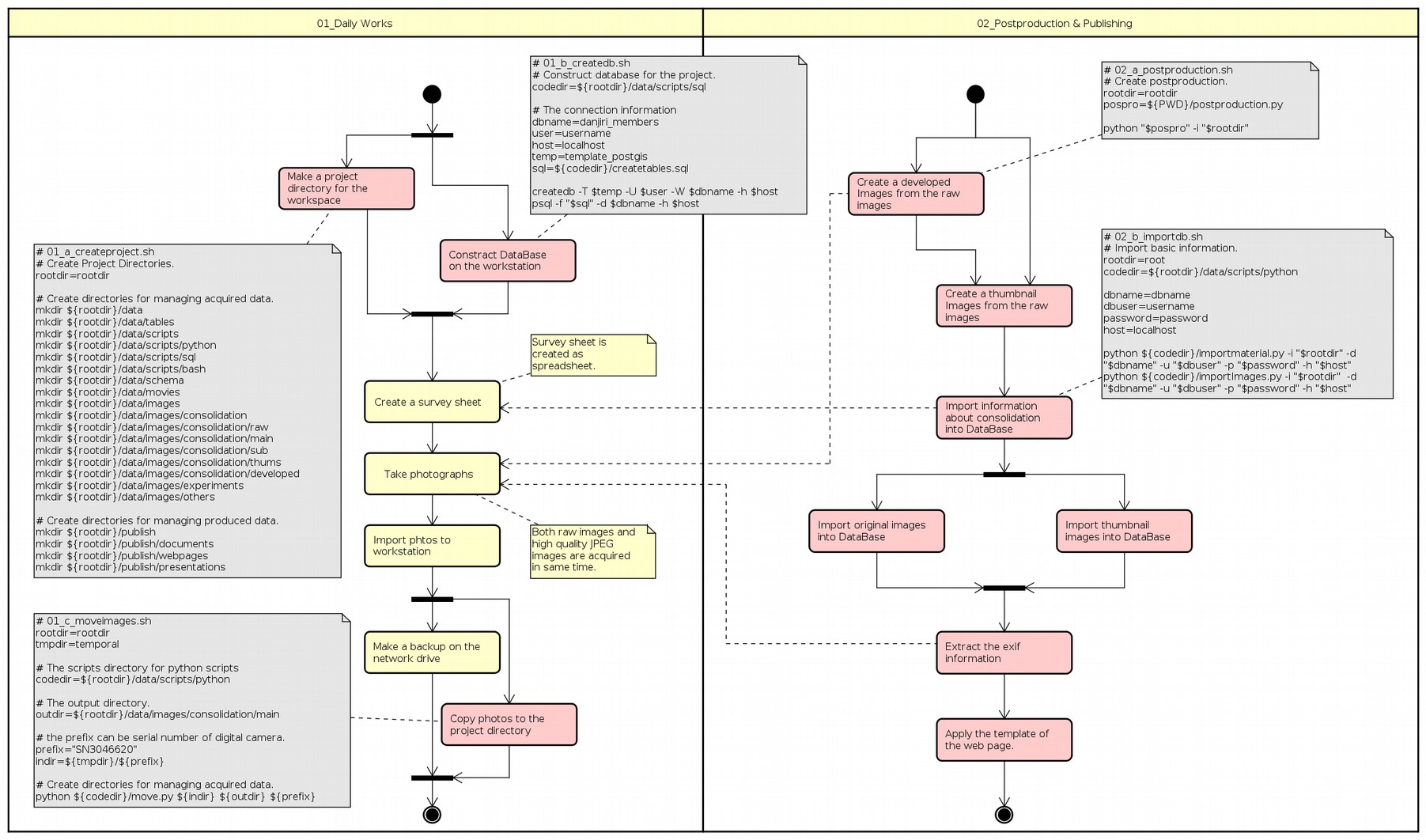

Figure 1 shows the workflow of constructing a digital archive using the MILC. In this figure, the workflows are denoted with UML activity diagrams, with automated activities in red, and yellow designating those activities conducted manually. Each automated activity is described by BASH scripts to ensure the clarity of specific procedures, and some call python scripts utilizing open source libraries. In practice, Graphical User Interfaces (GUI) should be provided for ordinal users.

This activity diagram is separated into two lanes, with the left lane showing the digital archiving workflow and the right lane representing the post-production and publishing workflow. In the digital archiving workflow, taking photographs, writing investigative reports, and transferring acquired images to the work station are manually conducted, whereas other activities are done automatically.

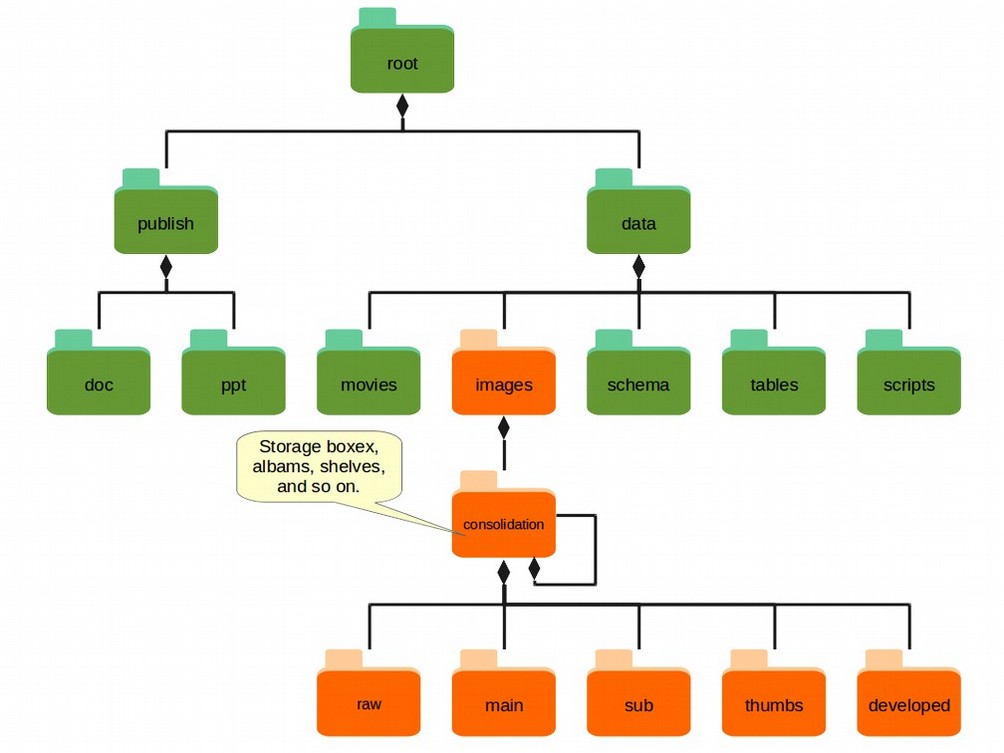

To perform these automatic activities, a working directory should be defined as shown in Figure 2. The raw images acquired are automatically copied to the “raw” directory and JPEG format images are initially copied to “main”, and then the raw images are developed and saved in the “developed” directory. Thumbnails are saved in “thumbs”. Finally, unused images are moved to “sub” directories. By defining the directory structure, all projects are generalized, and creating an automatic workflow becomes much easier.

3. The application schema

Promoting such shared and mutual use is essential and will help preserve local memories and knowledge for future generations. To do so, it is important to conform to conventional international standards (Fujimoto, 2009). The ISO 191XX series is a versatile information standard for database construction. This international standard is based on the idea of object-oriented GIS, and it defines a meta-model of geographic features and spatio-time objects. The ISO 191XX series is generally adopted for public geographic information suchas census or infrastructure data. However, it has many other possible applications. Additionally, this standard provides encoding rules by XML, and metadata, geometric information, raster format datasets and tabular form attributes can be denoted as XML elements. Therefore, this standard is also effective in terms of Long Term Preservation issues.

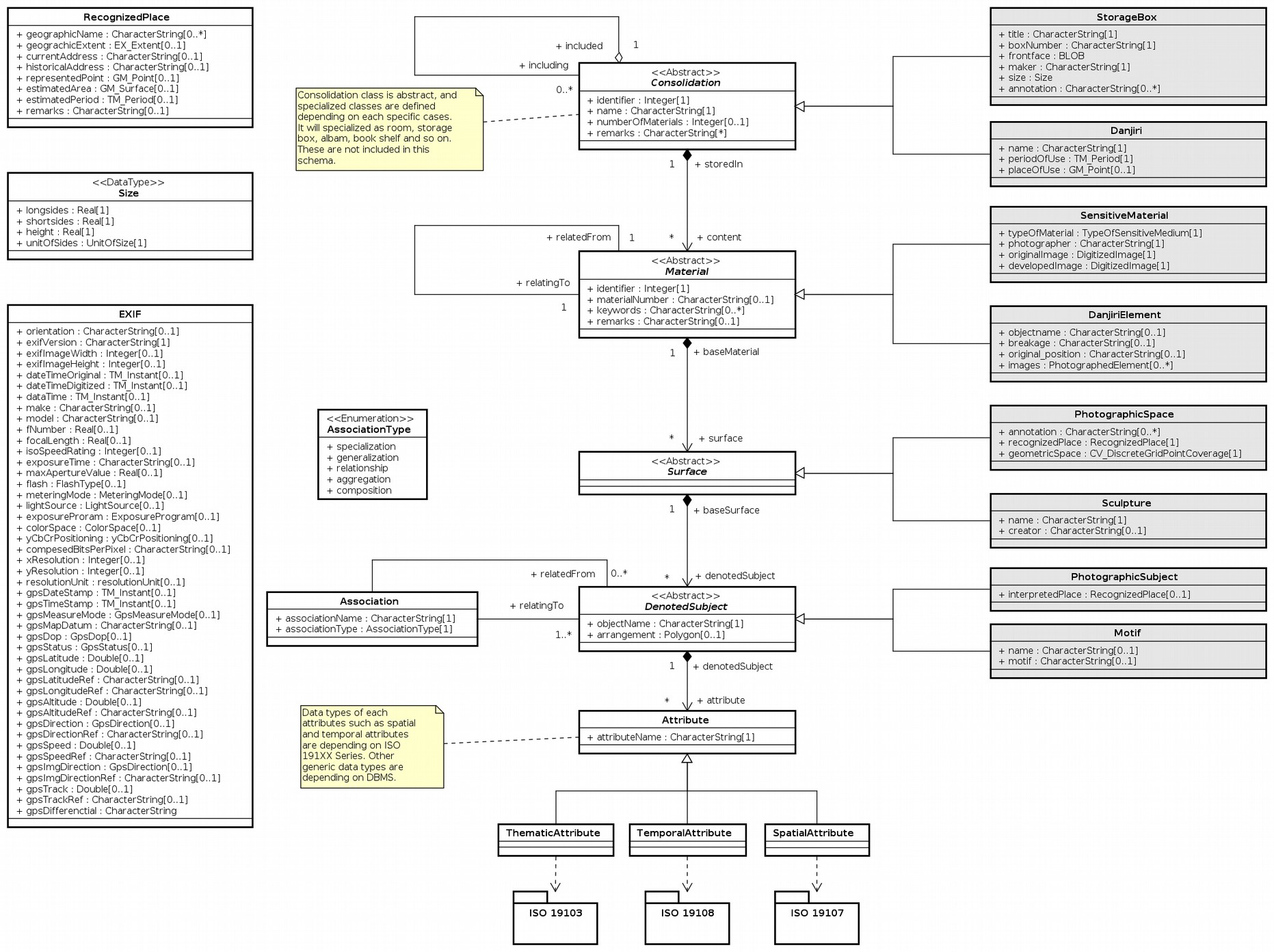

The Figure 3 is the application schema proposed in this paper, which enables the storage of unknown tangible as well as intangible cultural properties in compliance with the standard. This application schema is based on the proposed working flow, and weighs heavily in extendibility. The fundamental classes including the Consolidation class, Material class, Surface class and DenotedSubject class are Abstract classes, which are actually implemented in specific ways. The grey-colored classes are examples applicable to photographic dry plates and “ Danjiri” elements. The attributes for these classes are minimum essential attributes, and attributes relevant to each specific item can be defined using the Attribute class. This class specializes three classes: ThematicAttribute, SpatialAttribute and TemporalAttribute classes. Any kind of attribute can be defined using this classification.

4. Case studies

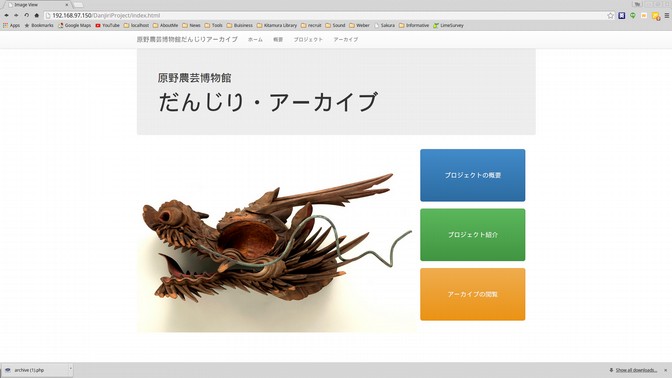

The proposed standardized workflow and the database schema have been used in two case studies. One is the digital archiving project of dry photographic plates taken between the Meiji period and mid-Showa period, while the other is a “Danjiri”, a traditional large wooden cart used for traditional Japanese festivals, which was completely destroyed by a flood.

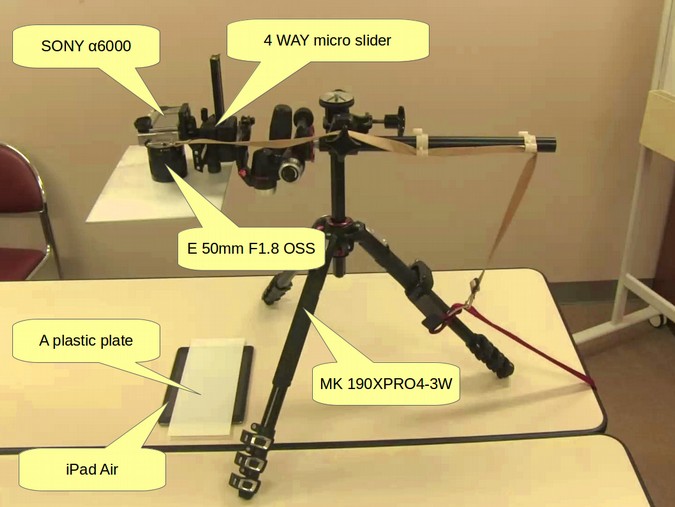

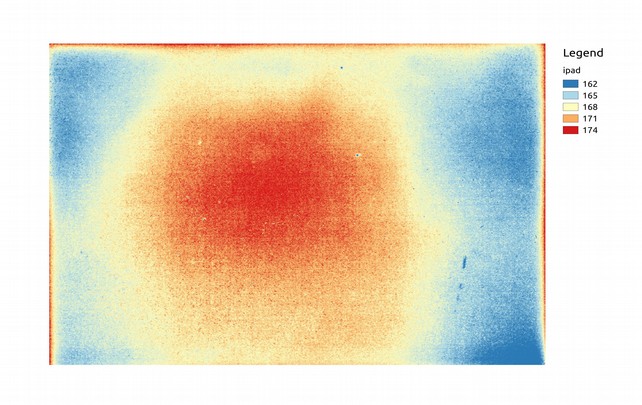

In the first case a tablet device, iPad Air, was used as a substitution for a light box, and SONY A6000 was used as a digitizing device (Figure 4 and Figure 5) (Fujimoto, 2015). By using a set of these ordinary devices with three workers, more than three hundred old dry plates were duplicated in about 13 hours in total. In this project, all of the operations were composed almost entirely of open-source software, and performed in batches. Although this project was successfully completed, some improvements were later found for making linkages between the acquired images and investigative reports and application schema.

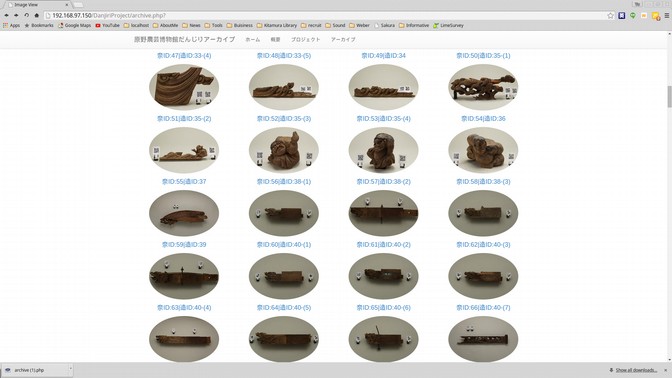

In the latter study, the digital archiving workflow and the application schema, originally designed for photographic dry plates, were modified for versatility, to make them applicable to the Danjiri elements. In this project, more than three hundred fragments of Danjiri elements were archived in one week by four workers with one day required for setting up the photographic studio, four days for taking photos, and two days for developing the digital archive system (Figure 6). In contrast to the former project, the digital archiving subjects were three-dimensional and lighting instruments were required. To achieve better results within a limited budget, a lighting studio was built using wooden blocks and domestic fluorescent lamps, which were procured on the site (Figure 7).

5. Conclusions

In digital archiving projects focusing on important cultural properties, intended objects are well known and professional and/or specialized equipment are used to achieve with the best possible results. However, to construct digital archives of locally-kept cultural properties, versatile and inexpensive methods are required. Additionally, a standardized workflow and database schema covering various kinds of materials should be considered.

In this paper, using the concept of WOA, a reasonable MILC is used as a digitizing device, and a standardized workflow enabling automation and database schema compliant with ISO 191XX are proposed. Because the proposed workflow, information schema and libraries utilize the existing international standard and open-source technologies, outcomes including metadata and source codes can be opened. This method is therefore effective in terms of the Long Term Preservation issues. These standardized methods have been tried in two different types of experimental case studies. Although both projects were successfully completed, some continual refinement is necessary to perform a fully automated workflow, especially post-production.

Finally, the methods proposed in this paper can be also applicable in disaster restoration. It is important to preserve memorial items of ordinary people such as family photo albums in order to incite the energy vital for the restoration process. Unfortunately, in fact, after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, a large number of mementoes and keepsakes of the local people were discarded. In such cases low-cost, swift and standardized digital archiving methods are essential.

- Fujimoto, Y. (2009). Information Standards for Cultural Heritage with The ISO 191XX Series, Proceedings of the 22nd CIPA Symposium, Kyoto, Japan.

- Fujimoto, Y. and Horiuchi, Y. (2011). Using Standards as a Bridge Between Traditional Research and Technologies in Protecting Cultural Assets, Proceedings of the 23rd CIPA Symposium, Prague, Czech Republic.

- Fujimoto, Y. (2015). Digitizing Dry Plates of the Kitamura Collection in Nara University Library, Memoirs of Nara University, No. 43, pp. 91-102. (Japanese)

- Lorie, R., A. (2001). Long Term Preservation of Digital Information. Proceedings of the first AM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, Roanoke, Virginia, New York: ACM-Press, pp. 346-52.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. (2006). Assessment of Situation with Settlements to Institute National Spatial Planning. (Japanese)

- Masuda, H. (2014). The Death of Regional Cities: A horrendous simulation Regional Cities Will Disappear by 2040 A polarized Society will Emerge, Discuss Japan – Japan Foreign Policy Forum, 18.

- The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2014). Estimation of the Japanese Future Population (Japanese).