Authors: Rombert Stapel

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: labour history, coin finds, historical gis, middle ages, northwest europe

Reconstruction of Labour Relations in the North Sea Region in the Late Middle Ages: Spatio-Temporal Analysis Using Historical GIS, Taxation Sources, and Coin Finds

1. Introduction

In this paper a range of maps, documents, data and archaeological finds are brought together in a historical GIS (Geographical Information System) to reconstruct different forms of labour and especially labour relations in existence in late medieval Northwest Europe. Starting from the Late Middle Ages, England and the Low Countries laid the groundwork for becoming two of the dominant powers in Europe and the world. The question is how this process of growth began. Often it has been coined with the rise of capitalism and the rise of wage labour as the predominant form of labour (e.g. van Bavel, 2007). The issue also touches on the Great Divergence debate. This debate centres around why and at what point in time Europe became the dominant continent in the world, surpassing the power and wealth of China, India, Japan and the Ottoman Empire (Pomeranz, 2000). England and the Low Countries play an important role in this debate and quite often the level of (real) wages is used as a determinant to study the emerging differences between Europe and other parts of the world (Allen, 2001). This opens up the question, however, how many people in a certain time and place actually worked for wages: an issue which questions the validity of real wages as (the only) measured variable (Lucassen, 2016).

2. Labour relations

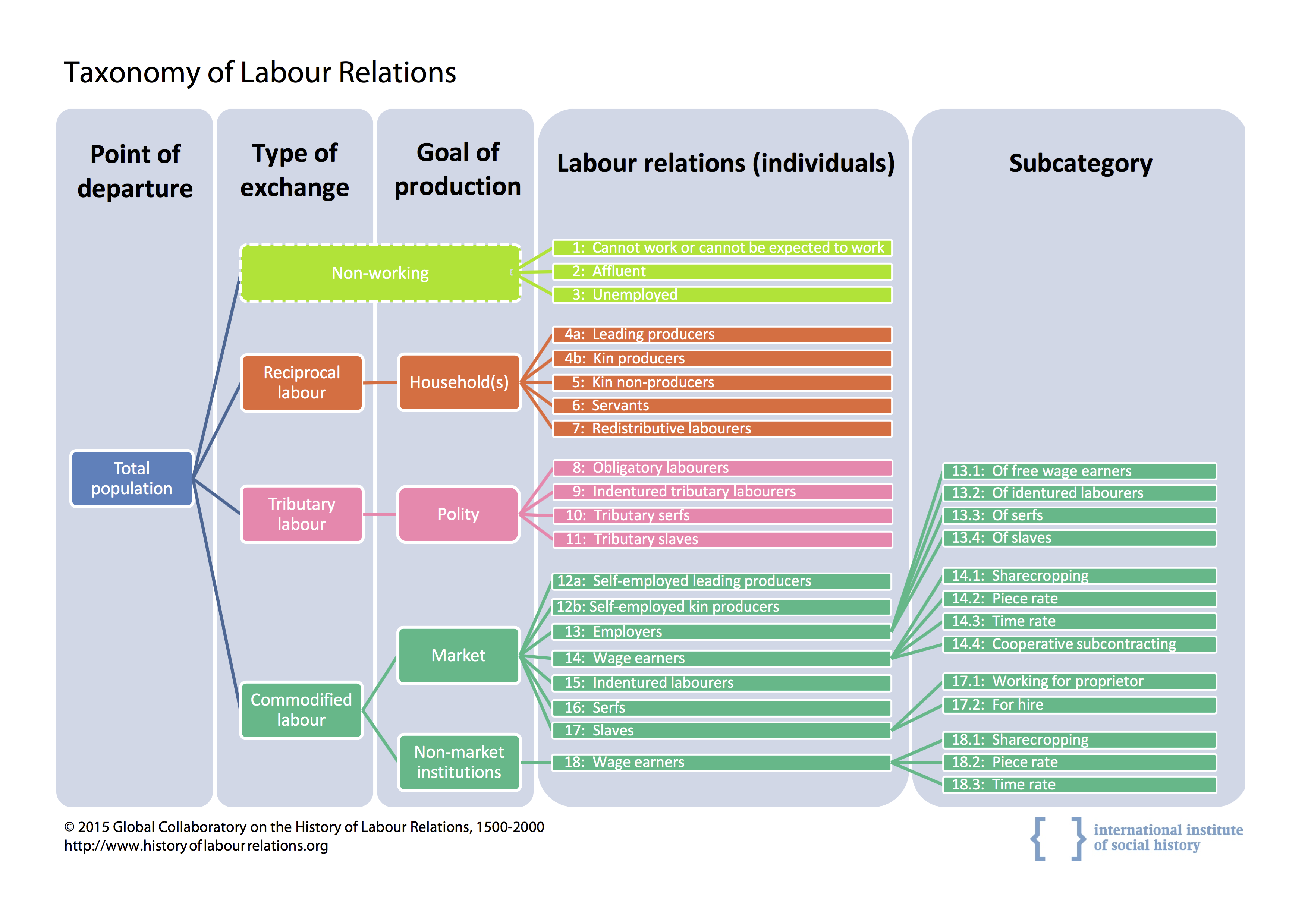

Labour relations can be defined as “for or with whom one works and under what rules” (Hofmeester et al., 2015). In the “Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500-2000”, a collaboration of researchers from all over the world, study these labour relations and especially shifts between them. To effectively compare different parts of the world across time, a uniform way of entering and presenting data as well as a taxonomy has been created (Figure 1). One of the advantages of this taxonomy is that it encompasses the entire population of an area, working and non-working, forces researchers to think about female labour participation (even if it is omitted in their sources), and includes various forms of labour, from reciprocal labour to wage labour, self-employment or slavery.

Studying societies other than modern ones can be especially difficult however. Lacking anything like modern census data, one has to be more creative to study different forms of labour across time and space and bring together a wide range of data and information. One may think about information on land use, vicinity of roads, waterways or coastlines, all proving modes of transportation, the vicinity of towns and monasteries, demographic density, documents related to taxation and many other. GIS is best equipped to present such combinations of different data, and is therefore at the core of the following two areas for which the labour relations are reconstructed.

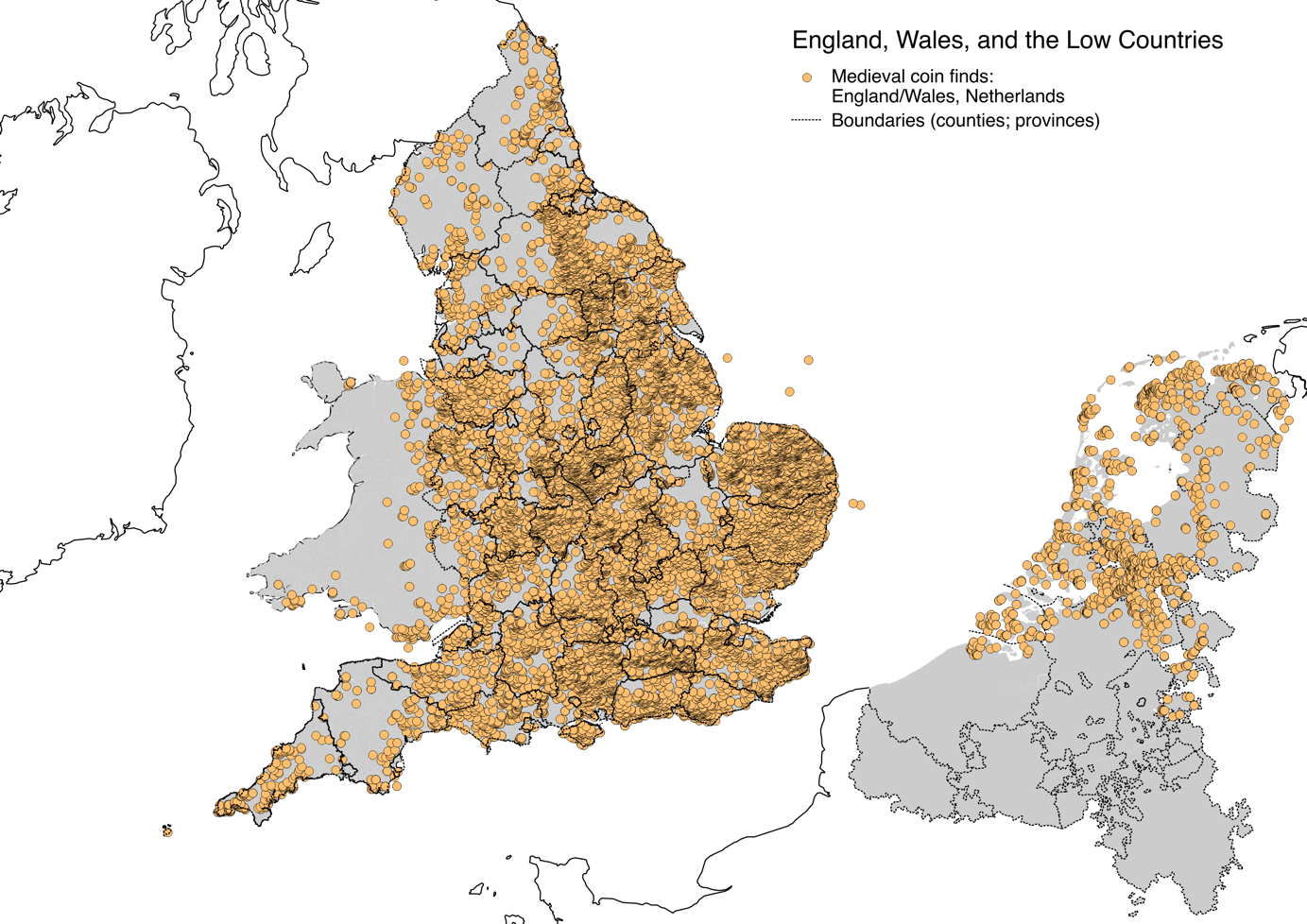

3. Reconstruction England/Wales

To come to a reconstruction of the labour relations in England and Wales a range of sources are combined, including the 1378-1381 Poll Tax records (Fenwick, 1998), the muster rolls of 1522, information on medieval markets (Keene et al., 2002; Keene and Letters, 2004), and GIS shapefiles of historical parish boundaries (Southall and Burton, 2004). From these sources regional variation in demography, market presence, and occupational structure can be extracted – albeit with many caveats. One of the main sources used for the reconstruction, however, are the tens of thousands of archaeological coin finds, by both amateurs and professionals. These are made available through the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) website (The British Museum, 2013-2015) (Figure 2).

The principal assumption behind using the coin finds is that the presence of small denominations, valued at a day’s wage or less, can function as a determinant of wage labour (Lucassen, 2014). Used in combination with figures on mint output, the coin finds can therefore be used to study the relative presence of wage labour; as well as regional differences and developments over time.

As the PAS database was formed by different people over a long period of time, various issues caused by inconsistent or erroneous data entry had to be solved. Much effort has gone into cleaning (especially place names) in the Portable Antiquities Scheme database and supplementing the numerous missing geographical coordinates. The following step is linking the coin finds to the data mentioned earlier, a complicated process that has started but for which much still has to be done in the coming months. In the end, the combination of available data provides us with an extensive toolbox to reconstruct the labour relations in late medieval England and Wales and to study the mechanisms that influence these labour relations, causing regional and temporal variation.

4. Reconstruction Low Countries

For the reconstruction of the labour relations on the other side of the North Sea, in the Low Countries a different approach has been chosen, although here too coin finds may be used in the end (De Nederlandsche Bank, 1997-2015). Starting point is the County of Holland. In 1494 and 1514 two sets of questionnaires were produced by the Burgundian/Habsburg rulers, intended to allocate a new round of taxes. The questionnaires had to be answered by representatives of all towns and heerlijkheden (a feudal administrative-judicial unit, precursor of modern municipalities) in Holland. They asked for information about the number of dwellings and parishioners; economic activities; how these economic activities developed in the past couple of years; land ownership; and tax-related issues. The questionnaires have been used to assess the state of the economy in Holland and study per capita growth (van Zanden, 2002).

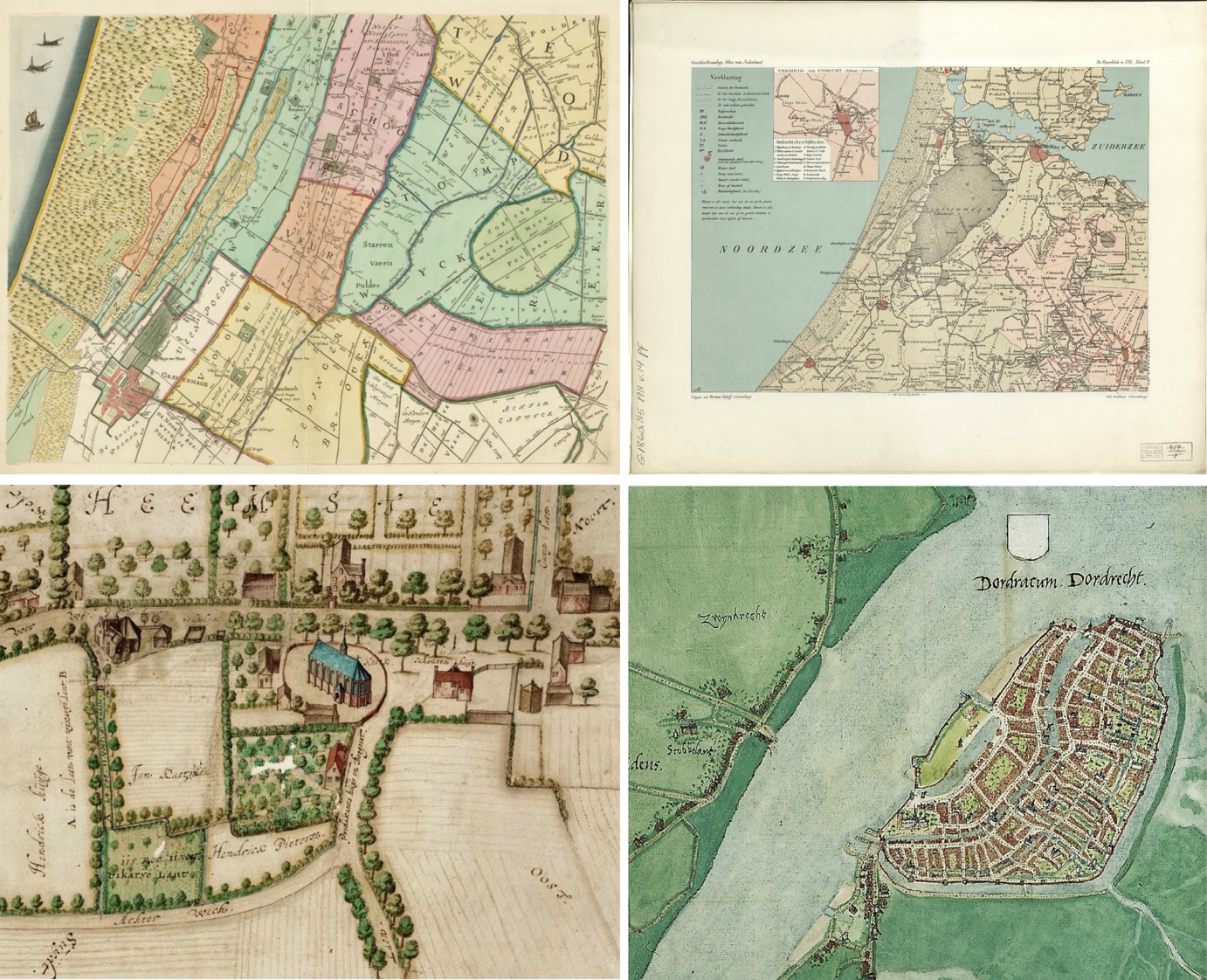

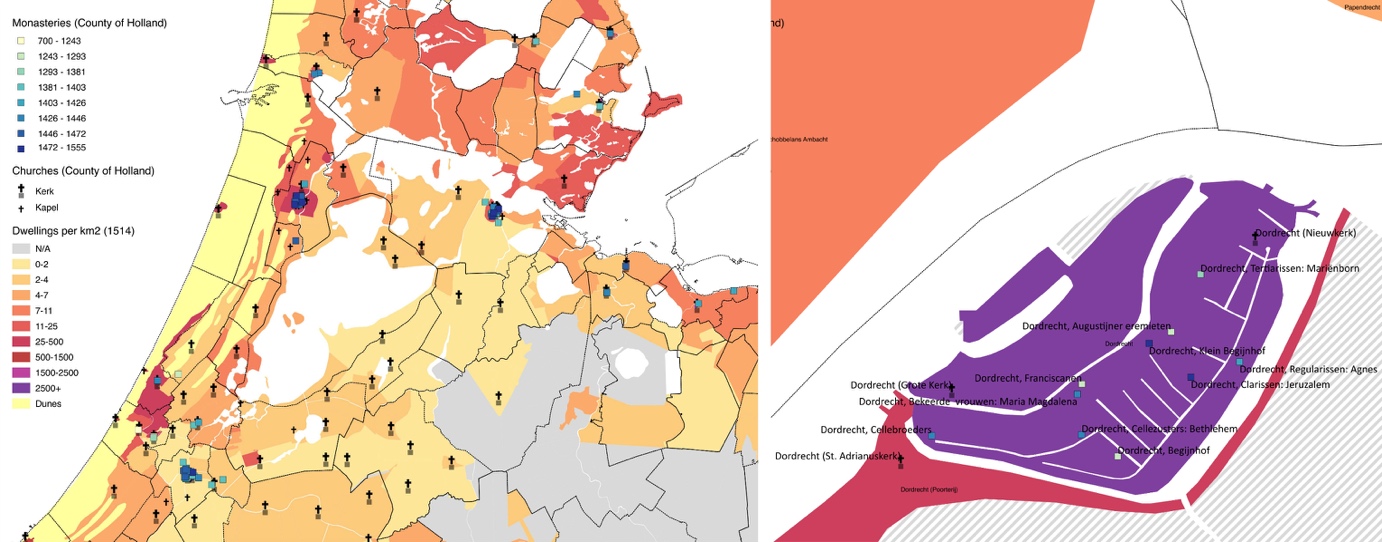

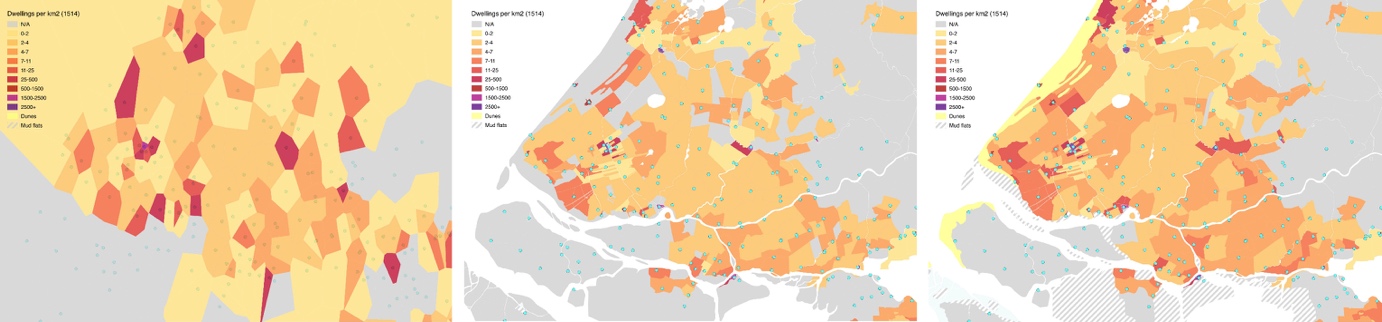

Never before have these questionnaires been mapped, which, for instance, would allow to combine the information with land use, the vicinity of monasteries and modes of transportation, and study in more detail regional variance in the county and – because of the nature of the questionnaires – changes over time between 1477 and 1514. For this purpose, a historical GIS of the administrative-judicial boundaries in this and some neighbouring counties was created from scratch. A wide range of digitised historical maps from the sixteenth to eighteenth century were used, in combination to the historical atlas of the Netherlands drawn by Anton Beekman at the beginning of the twentieth century (Figure 3; results in Figure 4). The maps were georeferenced and combined with information on natural and/or current (sometimes unchanged) municipality borders to reconstruct the location of the historical boundaries.

One of the immediate advantages was that using this GIS map, silent omissions in the questionnaires became visible (e.g. certain heerlijkheden that were not mentioned explicitly in the sources). Moreover, the advantage of using the historical boundaries, instead of just looking at the location of the villages and creating Voronoi diagrams for instance also becomes clear, as the maps provide much more detail and display patterns more clearly: see Figure 5.

By combining the questionnaires and the newly created geographical information with assumptions on household size, child and female labour participation, information on religious houses (using Goudriaan and Stuyvenberg, 2008), and other information a tentative reconstruction is made on the full range of labour relations present in the County of Holland in the Late Middle Ages.

5. Conclusion

In the end, the goal is to create a map that shows the presence and absence of various forms of labour and labour relations in the North Sea region. This allows us to study this part of the world, just before two new world powers emerged from here, and the role labour plays in this development. By using GIS (instead of displaying the information in tables for instance), the full potential offered by geographical information systems is made available: e.g. easily combining different forms of information, pinpointing developments to a certain point in time and space. Large-scale regional variation can therefore become a point of study, instead of hindering or difficult to grasp principle.

- Allen, R. C. (2001). The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War. Explorations in Economic History, 38: 411–447.

- De Nederlandsche Bank (1997-2015). NUMIS Muntvondsten Database. URL http://www.dnb.nl/over-dnb/nationale-numismatische-collectie/numis/index.jsp (accessed 10.31.15).

- Fenwick, C.C. (Ed.) (1998). The poll taxes of 1377, 1379, and 1381, Records of social and economic history. Published for the Bristish Academy by Oxford University Press, Oxford; New York.

- Goudriaan, K., Stuyvenberg, B. (2008). Kloosterlijst: beknopt overzicht van de Nederlandse kloosters in de Middeleeuwen.

- Hofmeester, K., Lucassen, J.M.W.G., Lucassen, L.A.C.J., Stapel, R.J., Zijdeman, R. (2015). The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500-2000: Background, Set-Up, Taxonomy, and Applications. URL http://www.historyoflabourrelations.org/ (accessed 10.31.15)

- Keene, D., Galloway, J., Murphy, M., Myhill, O. (2002). Metropolitan Market Networks, c. 1300-1600; London, its Region and the Economy of England.

- Keene, D., Letters, S. (2004). Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516.

- Lucassen, J.M.W.G. (2014). Deep Monetisation: The Case of the Netherlands 1200-1940. TSEG, 11: 73–122.

- Lucassen, L.A.C.J. (2016, forthcoming). Working Together. New Directions in Global Labour History. Journal of Global History, 11(1).

- Pomeranz, K. (2000). The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

- Southall, H.R., Burton, N. (2004). GIS of the Ancient Parishes of England and Wales, 1500-1850.

- The British Museum (2013-2015). Portable Antiquities Scheme. URL http://finds.org.uk/ (accessed 10.31.15).

- Van Bavel, B. (2007). The Transition in the Low Countries: Wage Labour as an Indicator of the Rise of Capitalism in the Countryside, 1300-1700. Past & Present, 195: 286–303.

- Van Zanden, J.L. (2002). Taking the measure of the early modern economy: Historical national accounts for Holland in 1510/14. European Review of Economic History, 6: 131–163.