Authors: Michał Choiński, Jan Rybicki

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: stylometry, American colonial literature, authorial attribution, editorial attribution, religious writing

Jonathan Edwards and Thomas Foxcroft: In Pursuit of Stylometric Traces of the Editor

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) is generally considered the most eminent and versatile thinker in early American history. His impact on the shaping of the theological thought and the preaching tradition of the colonial period was profound and long-lasting. Today he remains one of the best studied figures of the American past and different elements of his impressive output are continually reprinted by both academic and commercial publishing houses. Over his life Edwards authored more than a thousand sermons, hundreds of letters and a number of theological treatises. The Jonathan Edwards Research Center at Yale University edited and published most of these texts in their complete form as The Works of Jonathan Edwards, led by Harry Stout as general editor and Kenneth Minkema as executive editor. The series of almost thirty volumes is described by Phillip Gura, a former editor of Early American Literature, as the “most important editorial project in American cultural history in the past 50 years” (2004, 149). Edwards’ life is so well documented that there are hardly any stones unturned in the life of the Northampton divine. Especially, his relevance for the events of the Great Awakening, a powerful social-religious movement of colonial America, underwent close scrutiny and the most notorious sermon of America, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” which he authored, has been the studied linguistically, rhetorically and stylistically.

Like most people of his age, Edwards was a diligent diary-keeper and an avid letter-writer. His private texts offer a comprehensive insight into his daily struggles and ambitions – in consequence, the very writing and publishing process of his texts is relatively well documented. Yet, surprisingly – in spite of such extensive research conducted upon Edwards – the relationship between him and Thomas Foxcroft (1697-1769), his editor and literary agent has not been extensively studied.

Foxcroft was a minister at First Church in Boston, Massachusetts and Jonathan Edwards's ally in the pro-revival debate. Their collaboration began most probably in 1849; Edwards had great trust in his erudition and skill to carry out the authorial intent expressed point-by-point in his commentaries to the suggestions of corrections. Foxcroft sometimes included Edwards's correction verbatim, exactly as indicated by the author, at other times, he paraphrased them, while preserving the author's thought. Edwards entrusted Foxcroft with the editing, the correction and the publication process – as he writes in a letter sent from Stockbridge – a small mission he was sent to after the dismissal from his own parish of Northampton: “I should be glad that you would endeavor that this book may be printed in a pretty good paper and character, and may be printed correctly, and that particular care may be taken that the printer don't skip over a whole line as they sometimes do. And if the bookseller can be agreed with to let me have a number for the copy, it would be pleasing”. (30 June, 1752). Edwards also consulted Foxcroft about the correctness of his interpretation of other authors: "(…) it is very difficult, and almost impossible, for another to enter into all the views of a writer, or to know everything he has in view in all that he says; and therefore a little variation of sentiment, may much thwart and disappoint his design, insensibly to another. But this I should take as a very friendly part and much desire, that if you observe, that in any instances I have mistaken Mr. Williams' meaning, and misrepresented him, or in any respect injured him (…)" (30 June, 1752). The extent to which the style of the editor (whose idiosyncratic style can be described on the basis of numerous publications he himself authored) permeated the author's writings in this case has not been determined. The influence of Foxcroft's thought and style in Edwards's writings seems to be potentially very strong and demands close investigation and the stylometric approach seems a most fitting tool to be employed for such a study.

The analysis was performed with two quantitative methods: frequencies of most frequent words were compared between the texts using the Delta procedure (Burrows 2002); then, an analogous procedure (this time using Support Vector Machines) was used to look for traces of the editor’s signal in consecutive segments of several treatises by Edwards (“rolling.classify,” Eder 2015a). The analyses were performed with stylo (Eder et al. 2013), a package for R, the statistical programming environment (R Core Team 2014), postprocessed with Gephi network analysis software (Bastian et al. 2009).

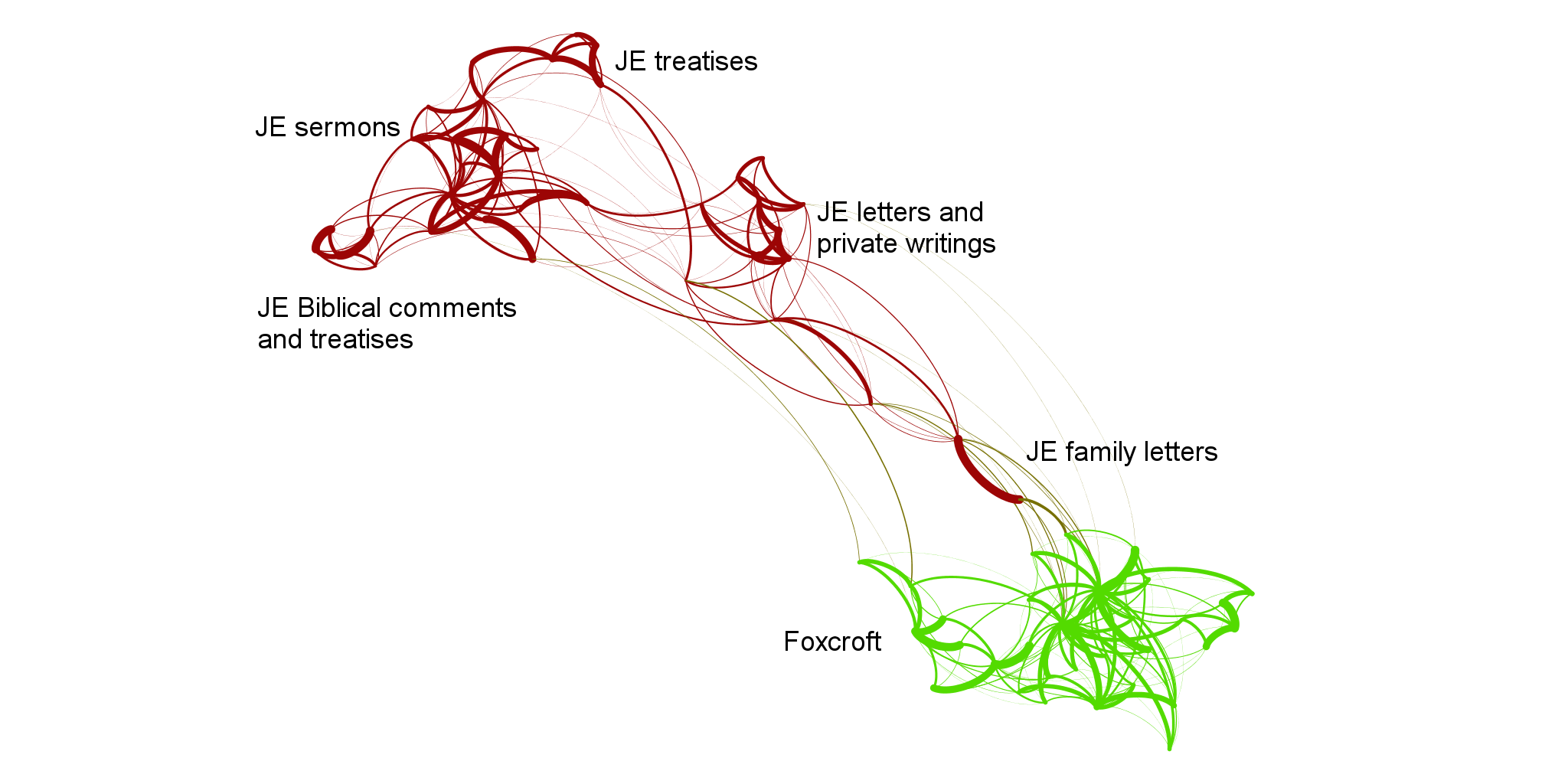

A general view of stylometric similarities and differences between the writings of Edwards and Foxcroft is presented in the network diagram in Fig. 1. It shows, above all, a good separation of the signal of the two preachers, especially when Edwards’s spiritual texts; sermons, treatises and Biblical comments are concerned, these, in turn, exhibit a degree of separation by subgenre – as opposed to Foxcroft’s generally more uniform stylometry.

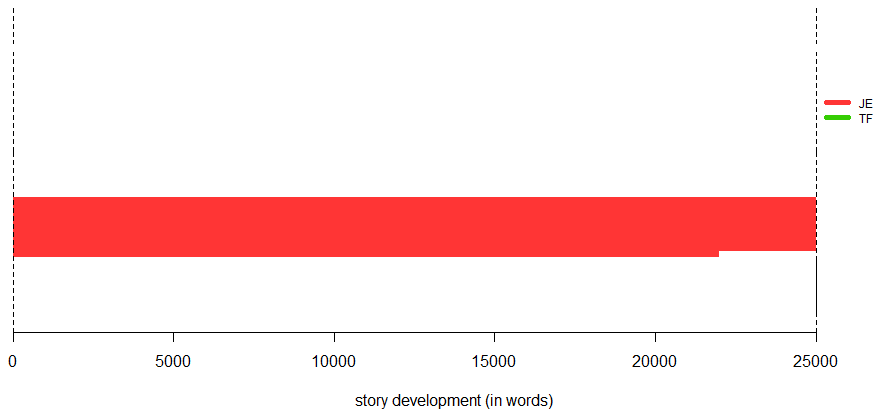

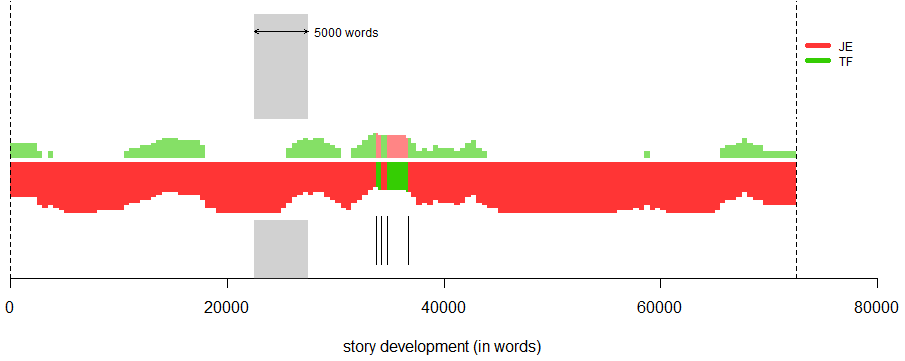

In the more detailed search for the editor’s signal with the “rolling.classify” method, longer texts by Edwards, i.e. his treatises, were compared against his own signal averaged over the rest of his oeuvre and against that of Foxcroft, bearing in mind the suggested caesura of 1749. Sure enough, consecutive segments of Edwards’s works written before that date exhibited no traces of the editor (as exemplified by Fig. 2), and then surfaced in a series of works (as visible in Fig. 3). Interestingly, the editor’s signal disappears again in 1758, the year of Edwards’s (not Foxcroft’s) death.

These results have two significant consequences. The first is that we have now produced a quantitative confirmation of the extent of collaboration between two major colonial authors. But the fact that the quantitative agrees so well with the qualitative (or historical) evidence also shows that editorial traces can indeed be found with stylometry, perhaps to a greater degree than we might have anticipated.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of project K/PBO/000331, supported by Poland’s National Science Center.

- Bastian M., Heymann S. and Jacomy M. (2009). Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

- Burrows, J. (2002). Delta: A measure of stylistic difference and a guide to likely authorship. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 17: 267-87.

- Eder, M., (2015a). Rolling stylometry. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30, first published online 7 April 2015, doi: 10.1093/llc/gqv010.

- Eder, M. (2015b). Visualization in stylometry: cluster analysis using networks. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30, first published online 3 December 2015, doi: 10.1093/llc/fqv061.

- Eder, M., Kestemont, M. and Rybicki, J. (2013). Stylometry with R: a suite of tools. Digital Humanities 2013: Conference abstracts, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, pp. 487-89.

- Gura, Philip F. (2004). Jonathan Edwards in American Literature, Early American Literature 39(1): 147-166.

- Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S. and Bastian, M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software. PLoS ONE, 9(6): e98679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098679.

- R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Wien, http://www.R-project.org/.