Authors: Maayan Zhitomirsky-Geffet, GIla Prebor, AmichaI Feigenboim

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: Social network, Jewish sages, Prosopography, Digital humanities

Towards a Cross-generation Social Network for Jewish Sages

1. Introduction

Construction and analysis of social networks for historical figures has lately become a popular approach in History and Prosopography (Keats-Rohan, 2007), Sociology (Wetherell, 1998; Roldán Vera and Schupp, 2006) and digital humanities (Rochat, 2015; Yamada, 2015). This approach is especially beneficial for providing a global view and automatic mathematical and statistical analysis for large historical corpora (Rossi et al., 2013), for which researchers are unable to gain much knowledge by even an exhaustive manual exploration.

Jewish Biblical and Rabbinic literature is a great source of ancient wisdom and cultural heritage. It includes a large amount of people such as prophets, political and religious leaders, sages and other historical figures. Amazingly, although these people were spread over the world and through different time periods, they were united and connected by the same text - the Bible. Therefore, the aim of this research is to propose and implement a methodology for construction of a cross-generation social network for Jewish sages to explore their inter-relationships on a large scale, using modern computerized tools for text analysis and graph mining (Rossi et al., 2013; Yamada, 2015).

2. The proposed methodology

At the first stage we define the corpus of the study and a reliable digital resource for this corpus. We work with the text of Mishna (2 nd century CE) and Talmud (4 th-5 th century CE). Next, the following information is retrieved from existing traditional research sources, such as encyclopedia of Jewish sages (as most of these sources have not been digitized, the person-related data is extracted manually and stored in the digital form):

- A list of sages for the selected corpora. One of the biggest challenges with sages’ names is their ambiguity and a large number of namesakes (Rochat, 2015; Keats-Rohan, 2007). To tackle this problem we add identifying discriminative features to each name (e.g. father’s name or place of birth).

- A list of basic relationships between sages, e.g. family relationships, teacher-student, time period, place, possessing a similar political/social/professional role, studying in the same institution, participation in the same event.

Finally, the above basic relationship list can be further extended with text-based relationships, such as sages who cite each other, disagree, or comment on the same section of the biblical text. This is achieved by automatically learning lexical patterns in which pairs of sages co-occur in texts and using them to extract the corresponding relations.

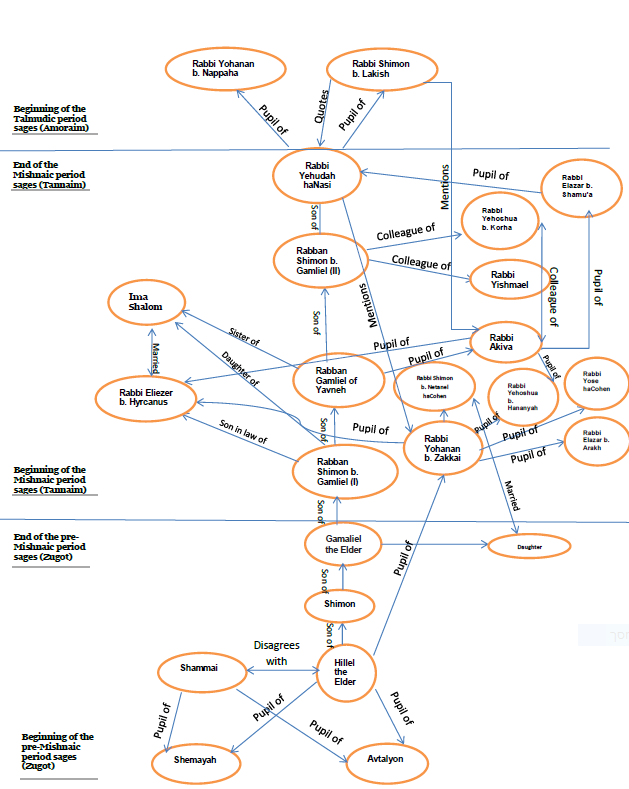

All the extracted data from multiple independent resources are digitized and integrated in the single database and can be queried and visualized by the common tools (e.g. Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009)). Figure 1 illustrates a fragment of the proposed type of the cross-generation social network for Jewish sages. Complex queries can be further answered by mining the network, e.g. whether a given pair of sages are related and how? What are all the various direct and indirect relationships of a given sage? Whether the same text segment cites sages from different time periods (meaning that it has been edited at a later period)? At the global level the social network helps identify the central figures/communities of the sages in different places, times, schools, dynasties, philosophical approaches, text segments, and citations according to the number of network relationships and their density, centrality and coreness (Rochat, 2015; Keats-Rohan, 2007). The historical data in the built network becomes accessible to researchers from the humanities and will take their research capabilities to the next level.

- Rochat. Y. (2015). Character network analysis of Émile Zola’s Les Rougon-Macquart. In Proceedings of DH 2015, Sydney.

- Roldán Vera, E. and T. Schupp. (2006). Network analysis in comparative social sciences. Comparative Education 42(3).

- Rossi, F., Villa-Vialaneix, N. and Hautefeuille, F. (2013). Exploration of a Large Database of French Notarial Acts with Social Network Methods. Digital Medievalist, 9.

- Wetherell, C. (1998). Historical Social Network Analysis. International Review of Social History, 43: 125-44.

- Yamada, T. (2015). Detection of People Relationship Using Topic Model from Diaries in Medieval Period of Japan. In Proceedings of DH 2015, Sydney.