Authors: Christopher W. Forstall, Lavinia Galli Milic, Nelis Damien

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: classification, text analysis, machine learning, Latin, epic

Approaches to Thematic Classification for Latin Epic

1. Background and Motivation

It has long been understood that Greek and Roman epic poems partake of a shared repertory of stock themes and typical scenes: the catalogue of heroes, the warrior arming for battle, the tempest, etc. These themes originally evolved under circumstances peculiar to oral-formulaic composition in archaic Greece, where they served the exigencies of real-time composition in performance by organizing poetic material into mnemonic chunks, each with a predictable internal structure (Rubin, 1995; Minchin, 2001). For later, literate Greeks, and still later for the Romans, who continued to develop the epic tradition, the use of these themes was no longer an aide to memory, but a complex intertextual gesture that formed one of the defining features of the genre (De Jong, 2014; Nünlist, 2009).

The study of elemental, thematic building-blocks in epic and related genres has a long history, through the twentieth century and even earlier, including work by Claude Levi-Strauss, Milman Parry, and Vladimir Propp. While catalogues and typologies of epic themes exist ( e.g., Edwards, 1992), at the same time significant disagreement remains over their definition and delineation. Here we take first steps towards automated detection of theme in epic, defining features that target scene-sized samples of text under in bag-of-words model, and applying both unsupervised and supervised classification methods.

Our research is on intertextuality in Latin epics of the Flavian period, and in particular the ways in which an intertextual relationship at the thematic level can support or undermine specific verbal allusions at the sentence or phrase level. The ability to automatically detect text reuse in Latin epic at the scale of individual verse lines is provided by tools such as Tesserae ( http://tesserae.caset.buffalo.edu), Musisque Deoque’s co-occurrence search ( http://www.mqdq.it/mqdq/cooccorrenze.jsp), and eTRAP’s forthcoming TRACER framework ( http://etrap.gcdh.de), so that it is now conceivable to generate an exhaustive list of all such correspondences between any two texts. Yet the same efforts have shown that simple text-reuse search alone cannot capture all of the allusions noted by professional commentaries, and that sensitivity to scene-level thematic parallelism would improve both recall and precision over a model based on single verse lines or sentences (Coffee et al., 2012).

Tesserae has in fact produced a prototype thematic search using topic modelling to create scene-level features (Scheirer et al., forthcoming). At the same time, work by the Memorata Poetis project affiliated with Musisque Deoque is carrying out systematic manual tagging of themes in Latin vernacular poetry (Ciotti et al., 2015). Both approaches—the supervised and the unsupervised identification of themes—show promise, although neither has been fully integrated into its respective parent project’s verse-level, text-reuse search tool. In the ongoing work presented here, we attempt to combine elements of each approach, comparing unsupervised, bag-of-words classifiers at the scene-level with manual tagging for specific, selected themes. Our ultimate goal is to combine similarity scores for thematic parallelism with existing phrase-level search tools’ scores for text reuse in order to improve their accuracy.

2. Method

We consider a corpus including the three more or less complete epics of the Flavian period—Valerius Flaccus’ Argonautica, Statius’ Thebaid, and Silius Italicus’ Punica—as well as three earlier poems to which our works of interest respond—Lucan’s Civil War, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Vergil’s Aeneid. These works are initially subdivided into samples of 50 consecutive verse lines. After lemmatization, tf-idf weighted feature vectors are calculated for each sample, dropping terms common to 50% or more of the samples, and the resulting feature set is reduced using principal components analysis to the most significant 500 components.

The samples still show a strong tendency to cluster by author despite the removal of very frequent words. Since our goal is to examine parallel variation across authors, we attempt to remove a characteristic ‘authorship signal’ from each author’s œuvre before classification. A mean vector representing the author is thus subtracted from every one of his samples.

In the unsupervised approach, we then perform k-means clustering on the corpus as a whole. Because we do not have any a priori set of themes to look for, we test multiple values of k in an attempt to identify the most stable number of clusters. For each possible value of k, we perform multiple repetitions and compare pairwise agreement among the resulting classifications using the adjusted Rand index. We also attempt to identify the most stable passages through comparison of error across repeated classifications using different offsets for our 50-line sampling window. For those passages most consistently classified across repetitions, we return to the text to investigate, through close reading, whether the passages indeed demonstrate meaningful similarity.

In the supervised approach, on the other hand, we begin by identifying scenes of interest using a set of a priori thematic categories—for example, battle scenes and storms at sea. We then attempt to train a classifier that can distinguish these types. Earlier work on this project has shown that certain thematic contexts can be separated at a coarse scale (e.g, love versus war, generally) using principal components analysis alone; however here we will attempt to achieve finer precision using support vector machines, a popular approach in stylometric tasks and one that has previously been applied to intertextuality in Latin in particular (Forstall et al., 2011).

3. Results

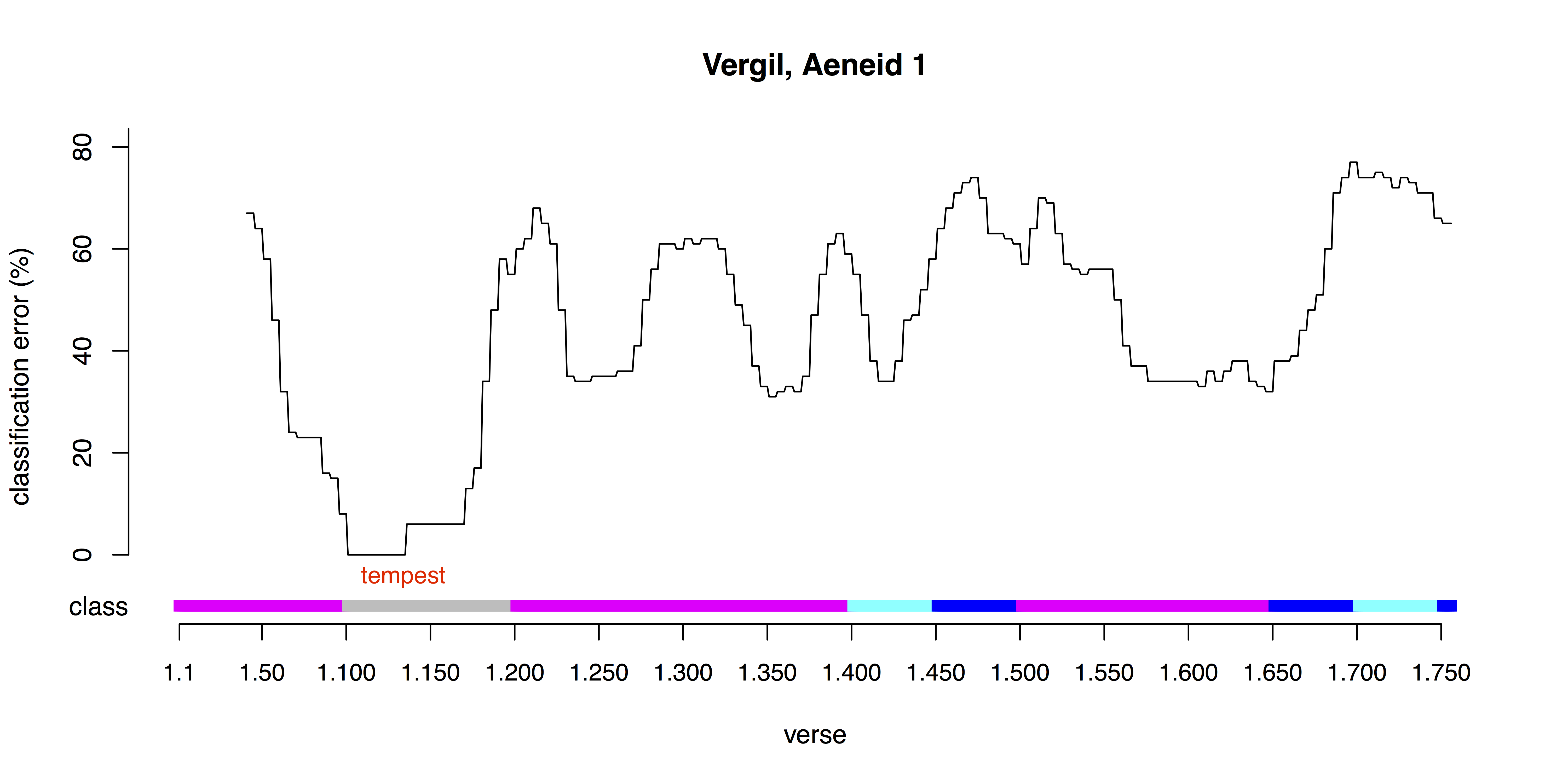

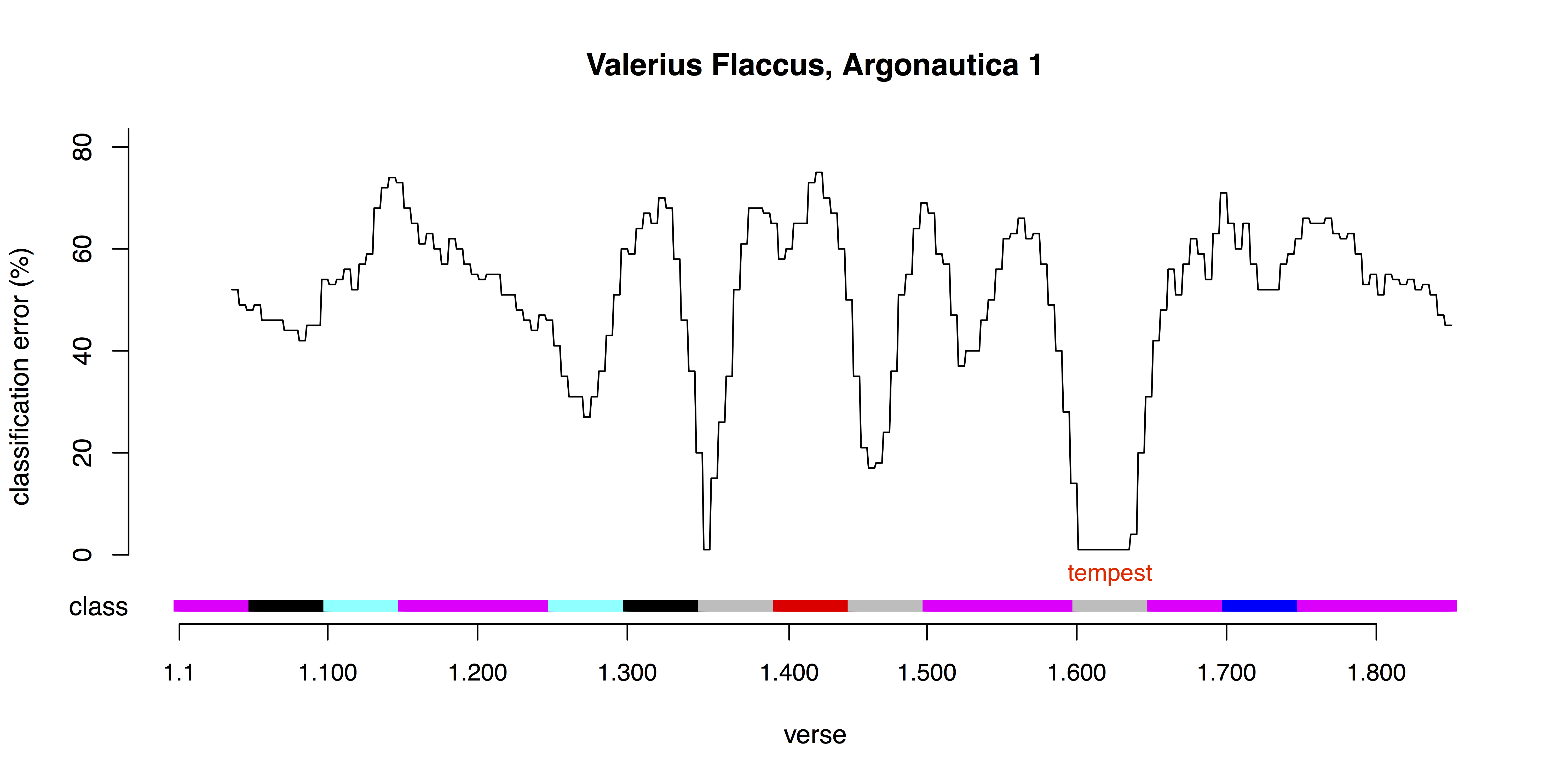

This work is ongoing, and one of our goals in presenting at DH 2016 is to elicit feedback that will help to shape the design of future experiments. At the same time, early results suggest that the supervised and unsupervised approaches may indeed meet in the middle. For example, many of the most stable passages in the unsupervised classification belong to a ‘nautical’ theme which includes as a subset the storm theme identified by human tagging. Across 100 different classifications of the six epics, using differently-offset sampling windows, the passages with the lowest rate of disagreement included characteristic descriptions of tempests in Aeneid 1 and Argonautica 1 (Figs. 1–2). The same class, and a high degree of stability, also marked nautical chase sequences in Aeneid 5 and Argonautica 8 as well as the recounting of the Argonauts’ story in Thebaid 5.

4. Implications

The concrete goal of this project is to provide a thematic feature set for automated intertext-detection, compatible with the phrase-based results of existing tools, so that, for example, otherwise slight verbal correspondences can be promoted where they occur within thematically parallel passages and thus are likely more interesting to readers. More generally, we would like to understand how stock themes function in epic intertextuality, and whether they can indeed be sufficiently modeled using a bag-of-words approach. To the degree that they can, we can say that thematic features are in fact made of words and exist on a continuum with the word-level bigrams matched by Tesserae, for example, instead of representing ‘deeper’, semiotic structures distinct from the word forms that appear on the ‘surface’ of the text (as in, e.g., Levi-Strauss, 1955)

- Ciotti, F., Mordenti, R., and Silvi, D. (2015). Thematic Annotation of Literary Text: The Case for Ontology. Paper presented at Humanités Numeriques et Antiquité, Grenoble, France.

- Coffee, N., et al. (2012). Intertextuality in the Digital Age. Transactions of the American Philological Association, 142(2): 383–422.

- De Jong, I. J. F. (2014). Narratology and Classics: A Practical Guide. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Edwards, M. W. (1992). Homer and Oral Tradition: The Type-Scene. Oral Tradition, 7 (2): 284–330.

- Forstall, C. W., Jacobson, S. L., and Scheirer, W. J. (2011). Evidence of intertextuality: investigating Paul the Deacon’s Angustae Vitae. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 26 (3): 285–96.

- Levi-Strauss, C. (1955). The Structural Study of Myth. The Journal of American Folklore, 68 (270): 428–44.

- Minchin, E. (2001). Homer and the Resources of Memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nünlist, R. (2009). The Ancient Critic at Work: Terms and Concepts of Literary Criticism in Greek Scholia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rubin, D. C. (1995). Memory in Oral Traditions: The Cognitive Psychology of Epic, Ballads, and Counting-out Rhymes. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Scheirer, W. J., Forstall, C. W., and Coffee, N. (forthcoming). The Sense of a Connection: Automatic Tracing of Intertextuality by Meaning. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. First published online October 20, 2014: 10.1093/llc/fqu058.