Authors: Bögel Thomas, Evelyn Gius, Janina Jacke, Jannik Strötgen

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: interdisciplinary collaboration, automated annotation, literary and linguistic concept modeling

From Order to Order Switch. Mediating between Complexity and Reproducibility in the Context of Automated Literary Annotation

1. Introduction

In the context of literary studies, which are mainly concerned with the hermeneutic interpretation of literary texts, narratological annotation can be helpful in at least two ways. First, the identification of narrative structures can point to peculiarities of the individual texts that are in need of interpretation, thereby advancing the generation of interpretation hypotheses. Second, since narrative structures can often be detected on the surface level of texts and described intersubjectively, narratological analyses may provide a robust and concrete backing for more comprehensive and complex interpretations.

Against this backdrop, the project heureCLÉA aims at developing a “digital heuristic”: a functionality that automatically annotates specific narrative features in literary texts. To achieve this, a corpus of short stories is manually and collaboratively annotated based on a narratological tagset (cf. Gius, 2015; Gius/Jacke, 2015a). The automation is subsequently achieved in a combined approach of rule-based NLP methods and machine learning techniques (cf. Bögel et al., 2015a). However, the automation process is complicated by a specific interdisciplinary conflict: the textual phenomena literary scholars are interested in are often very complex and closely interconnected, which seems to significantly hinder the automation process.

In this paper, we present our way of addressing this problem by way of example: we introduce the basic narratological concept of temporal order and its theoretical prerequisites/application conditions; we show how the concept’s complexity causes technical issues in the context of automation and how converting order to the stripped-down concept of order switch significantly enhances the automation results; finally, we explain in which way the new concept is still suited for literary analysis.

2. Collaborative manual annotation of temporal order

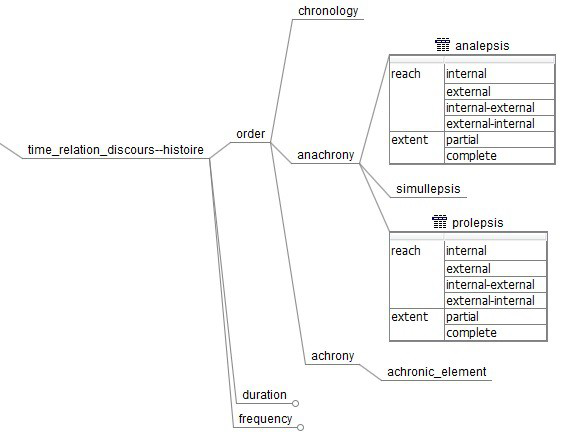

The discipline of narratology mainly deals with analyzing the (textual) features typical for narrative representation (cf. Meister, 2014). Narratological text analysis is based on often widely accepted narratological concepts or categories. The project heureCLÉA focuses on the operationalization of a subset of these categories: categories that describe temporal relations between a story and its representation. These categories are: order (when does an event happen? – when is it told?), frequency (how often does it happen? – how often is it told?), and duration (how long does it take to happen? – how long does it take to tell about it?) (cf. Genette, 1980). While these categories are reckoned comparably simple and straightforward in narratology, collaborative manual annotation revealed that they are not. We would like to illustrate this using the example of order (cf. fig. 1).

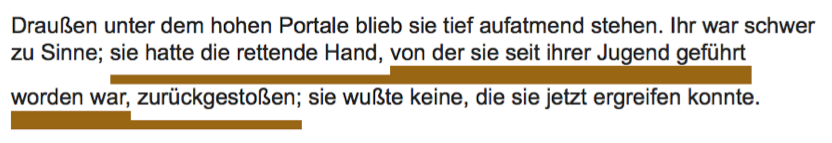

Basically, the events of a story can either be presented in chronological order or the chronology can be interrupted by “flashbacks” ( analepses in narratological terms) or “flashforwards” ( prolepses). Each analepsis and prolepsis can further be qualified according to their reach and extent. Whenever anachronies occur, the whole text passage constituting the anachrony is annotated as either analepsis or prolepsis. Furthermore, anachronies may be nested: they can contain further anachronies (cf. fig. 2).

The complexity of order annotation is significantly increased by the fact that the analysis of order showed to be dependent on a different narrative phenomenon: that of narrative levels. Narrative texts can contain embedded narrations, i.e., narrations within narrations. This occurs whenever a character in the story starts telling a story of their own (“new speaker”) or when counterfactual passages occur in a narration (“new world”) (cf. Ryan, 1991). As should be immediately plausible (at least for ontologically distinct narrative levels), it does not make sense to try and analyze the temporal relation between different narrative levels, i.e., between “actual” and counterfactual events in a story. It thus became necessary to establish an additional round of annotation preceding the annotation of order: we first had to identify the embedded narrations in a story, so that temporal order could subsequently be analysed for each narrative level separately.

3. Automation: from order to order switch

From a computational linguistic perspective, modeling order phenomena imposes interesting challenges that can be grouped into two types: aspects inherent to the phenomenon and data-specific issues.

3.1. Phenomenon-inherent aspects

Regarding characteristics of order phenomena, the aforementioned aspects of nestedness of order poses interesting challenges. As order phenomena are inherently nested, they yield a tree structure of annotations with multiple parent-child relationships. While there are models to formalize and predict tree structures (e.g., in the area of grammars), the prediction is orders of magnitude more complex than the prediction of linear or independent annotations, where complexity in this sense means the amount of training data required to sufficiently model the problem.

In addition, the span of order annotations is highly heterogeneous comprising few tokens as well as multiple paragraphs. Finally, while a sequence classification approach would be suitable to annotate a sequence of tokens representing a specific order, additional aspects of the data at hand impede sequence classification. There is thus no clear annotation target that should be classified by a classifier.

3.2. Investigating the data

To assess the annotation quality and thus feasibility of automation, we investigated the primary annotations of order phenomena. Investigating the number of different annotations for the entire training set (21 documents, see below) where two annotators agree with each other – which was the case for 90% of all annotations – revealed that there is an imbalance of annotations with seven times as many analepses (696) than prolepses (98).

This imbalance poses three major problems for statistical modeling and machine learning: sparsity, noise and class- imbalance. Sparsity occurs for annotations that are not well reflected in the data set, such that a classifier cannot find enough evidence to integrate the annotations into its model. This issue is reinforced by noise, meaning inconsistencies in the annotations. One sequence of tokens could either represent a certain order phenomenon or just reflect a change of narrative levels, making it hard for the classifier to learn anything meaningful. Finally, class-imbalance imposes a bias on the classifier, resulting in the phenomenon that the minority class is rarely predicted or even not considered at all.

3.3. From order to order switches

Investigating the annotations revealed that sub-sentences serve as boundaries for order switches. Thus, to solve the issues mentioned above, we do not attempt to classify order phenomena directly but instead predict for each sub-sentence whether it introduces a switch of the order in the previous (sub-)sentence. While this is, of course, a simplification of the task, it allows us to model the task as a binary classification problem with a clear annotation target and alleviates the issue of sparsity because we do not distinguish between different types of order annotations. To generate training and test data from the original manual annotations of order, we determine all sub-sentences where the order annotation changes, and tag them as order switches.

The resulting annotation statistics are shown in table 1 and indicate that switching from order to order switch increases the number of positive instances in the training set to 1802, meaning that 1802 out of all sub-sentences introduce order changes. Note, however, that the issue of imbalanced data still exists.

| annotation | count | percentage |

| order-switch | 1802 | 12.3% |

| no switch | 12871 | 87.7% |

tab. 1: New training set based on order switches

3.4. Evaluation and experiments

Our training set consists of 21 documents from various authors of the 20th century, comprising about 80,000 tokens in total (cf. Bögel et al., 2014). For evaluation, four additional documents were annotated.

Overall, we use 21 features (presented in the appendix) to model order changes. We investigate different aspects of tense (e.g., whether a sub-sentence and the previous (sub-)sentence use the same tense), direct speech, temporal signals (cf. Bögel et al., 2015b), as well as structural features, e.g., paragraph boundaries. Finally, we add features to capture whether the sub-sentence represents a change of narrative levels rather than order.

As mentioned above, the class-imbalance between positive and negative instances remains problematic. To reflect this during the evaluation, we perform randomized re-sampling (cf. Japkowicz/Shaju, 2002) with replacement on the training data which allows us to artificially adjust the spread between two classes. Table 2 contains the evaluation results for different spreads using Random Forests (Breiman, 2001) for classification. The more uniform the distribution of both classes and thus the lower the spread, the better the results. With the best setting (spread = 1:2), we are able to achieve a balanced result with a high F 1-score of 81.4%.

| setting | precision | recall | F 1 |

| spread=1:6 | 20.4 | 14.7 | 17.1 |

| spread=1:3 | 74.9 | 77.5 | 76.1 |

| spread=1:2 | 79.1 | 83.9 | 81.4 |

| spread=1:1 | 76.2 | 79.5 | 77.8 |

tab. 2: Evaluation results for different spreads

Overall, the high performance confirms our hypothesis that breaking the complex task of predicting order phenomena into more manageable sub-steps yields promising results.

Nevertheless, we expect that even more complex narrative phenomena can be automatically annotated in the future. As simple narrative concepts have now been tackled successfully, their annotations could be exploited as features to predict more complex phenomena.

4. Conclusions

Our aim to automate the annotation not only of basic and rather straightforward linguistically encoded temporal aspects like tense and temporal signals (cf. Bögel et al., 2014; Bögel et al., 2015b), but also of more complex phenomena like order in heureCLÉA was a long shot. However, by cautiously reducing the concept’s complexity in active dialogue between computer scientists and literary scholars, we were not only able to yield good annotation results, but also to end up with a concept that is still of value for literary scholars: while deviations from the chronological presentation of a story cannot be automatically predicted in as much detail as in manual annotation, the automated functionality still serves as a robust heuristic pointing to temporally interesting passages upon which literary scholars can base their in-depth analyses and interpretations. By finding a way to include consideration of narrative levels in the automation, the original order concept was not compromised with regards to its conceptual key features. The transformation from order to order switch is therefore yet another example of successful collaboration between literary scholars and computer scientists in heureCLÉA (cf. Gius/Jacke, 2015b): only a frequent exchange between the involved parties can yield results satisfactory to both sides. We are optimistic that this kind of collaboration has the potential to achieve a functional automated annotation of even more complex narrative phenomena – provided that the phenomena in question are of the kind that their analysis allows for a certain degree of inter-annotator agreement. 2

[Page]

5. Appendix: feature set for order switch prediction

| tense | tense of target tense of target -1 same tense for target&target -1? target contains imperative? target -1 contains imperative |

| direct speech | target starts direct speech? target -1 starts direct speech? target within direct speech? target -1 within direct speech? |

| structural | target occurs after paragraph boundary? target is at beginning/end of sentence? length of target relative to entire sentence |

| temporal signals | target contains temporal signal? target starts with temporal signal? string of temporal signal first token of temporal signal preposition of temporal signal last token of temporal signal |

| narrative levels | target in conjunctive mood? target -1 contains utterance verb? |

- Bögel, Th., Strötgen, J. and Gertz, M. (2014). Computational Narratology: Extracting Tense Clusters from Narrative Texts. Proceedings of the 9th Edition of the Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC’14), pp. 950-955, Reykjavik, Iceland. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2014/pdf/849_Paper.pdf (accessed 02.03.2016).

- Bögel, Th. et al. (2015a). Collaborative Text Annotation Meets Machine Learning. heureCLÉA, a Digital Heuristic of Narrative. DHCommons 1. http://dhcommons.org/journal/issue-1/collaborative-text-annotation-meets-machine-learning-heurecl%C3%A9-digital-heuristic (accessed 02.03.2016).

- Bögel, Th., Strötgen, J. and Gertz, M. (2015b). A Hybrid Approach to Extract Temporal Signals from Narratives. Proceedings of the International Conference of the German Society for Computational Linguistics and Language Technology (GSCL’15), pp. 106-107, September 20-October 2, Duisburg-Essen, Germany. http://gscl2015.inf.uni-due.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/gscl2015-proceedings.pdf (accessed 02.03.2016)

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine learning, 45 (1): 5-32.

- Brunner, A. (2013). Automatic recognition of speech, thought, and writing representation in German narrative texts. Literary and Linguistic Computing 28(4): 563-75.

- Genette, G. (1980). Narrative Discourse. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Gius, E. (2015). Erzählen über Konflikte: Ein Beitrag zur digitalen Narratologie. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Gius, E. and Jacke, J. (2015a). Zur Annotation narratologischer Kategorien der Zeit. Guidelines zur Nutzung des CATMA-Tagsets. http://www.heureclea.de/guidelines (02.03.2016).

- Gius, E. and Jacke, J. (2015b). Informatik und Hermeneutik. Zum Mehrwert interdisziplinärer Textanalyse. Zeitschrift für digitale Geisteswissenschaften 1. http://www.zfdg.de/informatik-und-hermeneutik-zum-mehrwert-interdisziplin%C3%A4rer-textanalyse (accessed 02.03.2016).

- Japkowicz, N. and Shaju, S. (2002). The class imbalance problem: A systematic study. Intelligent data analysis 6(5): 429-49.

- Meister, J. C. (2014). Narratology. the living handbook of narratology. http://www.lhn.uni-hamburg.de/article/narratology (accessed 02.03.2016).

- Ryan, M.-L. (1991). Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Storm, T. (1861). Veronika. https://textgridrep.de/browse.html?id=textgrid:vtkx.0 (accessed 02.03.2016).

This precondition may be the critical factor in some automation attempts, e.g., the automated annotation of free indirect discourse that lacks a sufficient amount of reliable indicators (cf. Brunner, 2013). Its determination is rather interpretation-dependent and thus the phenomenon is barely qualified for high inter-annotator agreement.