Authors: Elizaveta Kuzmenko, Boris Orekhov

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: named entities recognition, toponyms, Russian poetry, distant reading

Geography Of Russian Poetry: Countries And Cities Inside The Poetic World

Our paper is dedicated to two major problems: the first problem is the digital one and the second problem is connected to the humanities. The first problem involves automatic extraction of named entities, and the second problem is connected to the usage of toponyms in poetic texts. Correspondingly, our research comprises two parts: automatic processing of a huge amount of texts from the corpus of Russian poetry and revealing major trends in the functioning of toponyms during the history of the Russian poetry from 18 to 20 centuries.

Our research is based on the data from the poetic corpus which is a part of the Russian National Corpus 1. This corpus includes the main texts belonging to the Russian poetry from all the periods of its history, up to the 20th century. The principles of text selection in the poetic corpus are described by its creators (Grishina et al., 2009). The size of the corpus is approximately 11 million word tokens.

Up to the present moment, research papers considering toponyms in the Russian poetry described a concrete toponym from the perspective of an isolated text or a particular author (see, for example, Mednis, 1999). Our approach is quite different: we describe tthe geography of Russian poetry as a whole, consistently to the framework of distant reading (Moretti, 2005; Moretti, 2013). Thus, the result demonstrates global trends in the usage of toponyms in Russian poetry as a system.

We used two different technologies to extract geographic entities from poetic texts, and the comparison of these two approaches is one of the results of our research. The first technology is a proprietary commercial software Textocat 2, which is based on machine learning with the use of nonfictional texts as a training sample. The creators of this software claim that the F1-measure for the retrieval of named entities is 0.75. However, it is expected that the performance would be much lower in the case of poetic texts, because the language of poetry differs radically from the language of prose.

The second approach we use is a self-made tool for the extraction of toponyms based on the dictionary of geographical names. We are forced to create such a tool because there is no open-source software for the extraction of toponyms for Russian. As a basis for our dictionary of geographical names, we use the list of toponyms from the Wikipedia.We compared the figures retrieved with our approach to the ones resulting from Textocat. We used for evaluation a sample of toponyms consisting of countries and cities. The comparison showed that Textocat retrieves only 25.7% of country names and 19.3% of city names that are found with our tool. In addition, Textocat makes a lot of mistakes; for example, locative pronouns там 'there' and где 'where' are retrieved among geographical entities. The words страна 'country' and город 'city' are also included by Textocat in the list of found toponyms.

As we can see, the dictionary-based approach proves to be more efficient, and in further results we consider only the data extracted with this method.

First, we will look in detail on the names of countries extracted from poetic texts. The distribution of mentioning countries is presented in Table 1 (six most popular countries are taken):

Table 1. The most frequently mentioned countries.

| Country | Number of times it is mentioned |

|---|---|

| Russia | 2744 |

| France | 283 |

| Italy | 241 |

| Poland | 201 |

| Lithuania | 160 |

| Greece | 159 |

| Egypt | 151 |

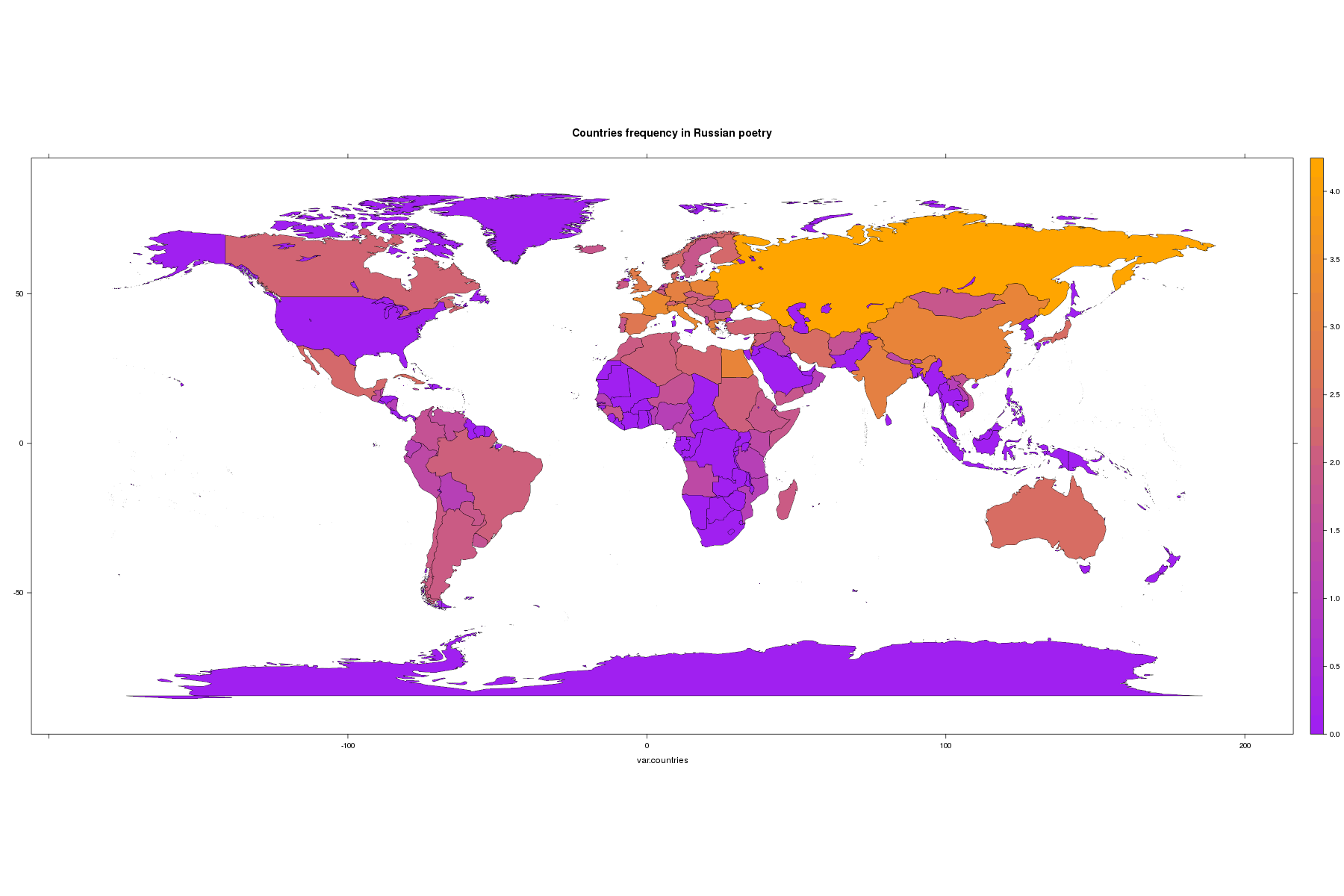

The distribution of names for all the world countries is presented on Figure 1. Before building this map, the frequencies of countries' names were normalized, so we counted the number of poetic pieces in which the name was met, not the occurrences.

It is not surprising that Russia takes the first place on this list. The top of the list is occupied mainly by the European countries. The second place goes to France, because its influence on Russian culture was immense: in the 19th century French was even the main language of communication for Russian aristoсracy. Italy can be found on the third place, despite the fact that it is very important for the poetic mythology in the 19th century, and it was the main geographical location for the poetry of the eminent Russian poets Batyushkov and Baratynsky.

It should also be mentioned that the Russian poetry does not favor exotic countries and it is primarily occupied with the European neighbors of Russia (Poland, Lithuania, Greece). The only African country in the top of «poetic» countries is Egypt, which is renowned for its ancient mythology and pyramids with considerable poetic potential.

The second exotic country in our list is India, and it is followed by countries of the specific «Russian East», which includes Georgia and Iran. The most popular country from the Middle East is Lebanon. If we take a look at the contexts in which Lebanon is used, we see that this country is mostly mentioned due to the cedars of Lebanon. It is unexpected that Lebanon appeared to be more frequently mentioned than the Northern European countries (Finland, Norway, Denmark).

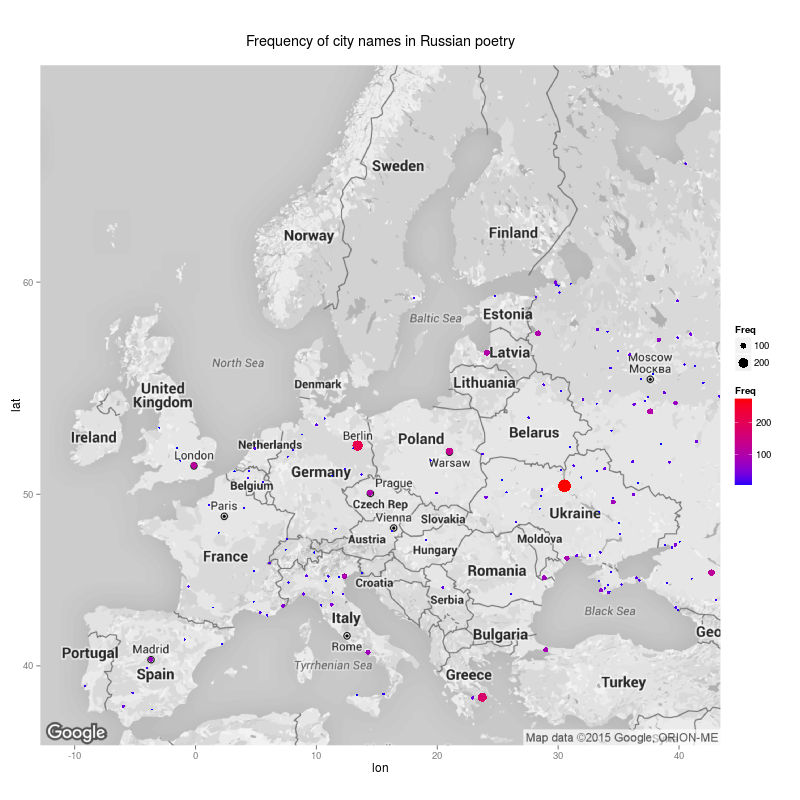

Now we will consider mentionings of city names in Russian poetry. The frequency of names for European cities can be seen on Figure 1. This map reflects mentioning of cities with frequency lower than 690. Thus, we drop such cities as Moscow (with frequency of 2470), Rome (with frequency of 1135), Paris (771), and Saint Petersburg (695). Let us note that Rome is more frequent in Russian poetry than Paris, although France dominates Italy in the list of countries' mentionings. Also, we do not mark on the map those cities whose frequncy is lower than 4.

As we can see from the visualization, the most «poetic» cities from the point of view of Russian poets are concentrated near Moscow and Saint Petersburg, and also in Ukraine and Northern Italy. Ukraine was a part of Russia during the history of Russian poetry, but the specifically Russian territory demonstrates uneven distribution of mentionings, whereas Ukraine is densely populated with poetic cities. The Crimea draws attention as the most «charged» with poetic cities, though it is not a big territory itself. Sea coasts of Southern Europe generally provide us with cities popular among Russian poets.

Continental Europe is not frequently mentioned in the poetry, with an exception of the capital cities of Prague and Warsaw. The blank spaces can be found throughout the territories of France and Germany. Scandinavian cities also don't have considerable amount of mentionings within the history of Russian poetry.

Another interesting opposition lies in the distribution of mentionings for Romanic and Germanic cities. As we can see, Russian poets prefer the cities of Italy, France, Spain and Belgium, whereas cities of Britain, Germany and Netherlands appear to be less poetic. Probably, the reason underlying this distribution is not the language, but the confession. Apparently, Russian poets prefer catholic countries to the protestant ones, and Vatican itself can be found on the 17th place judging by the frequency of mentioning countries in the Russian poetry.

To sum up, mentioning of toponyms presents interesting data which can be used to reveal trends in the poetry, and those trends help to describe Russian poetry as a system. It is impossible to notice such patterns with manual or visual analysis of poetic texts, but it can be achieved through digitalization of poetry and computational analysis of the texts.

In future we plan to extend our research towards extraction and interpretation of other types of geographic entities: water bodies, geographical places, regions, streets, eminent buildings and locations. This would require dealing with the change of names throughout the time periods. We also plan to investigate the usage of geography in the particular poets' works.

- Grishina, E., Korchagin, K., Plungian, V. and Sitchinava, D. (2009).Poeticheskij korpus v ramkah NKRYa: obschaja struktura i perspektivy ispol'zovanija. 'Natsional'nyj korpus russkogo jazyka: 2006-2008. Novye rezul'taty I perspektivy'. Saint Petersburg, pp. 71-113. [Poetic Corpus in RNC: general structure and using perspectives]

- Mednis, N. (1999).Venecija v russkoj literature. Novosibirsk. [Venice in the Russian Literature].

- Moretti, F. (2005).Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract models for a literary history. Verso.

- Moretti, F. (2013).Distant Reading. Verso.