Authors: Richard Zijdeman, Rombert Stapel

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: labour history, allocation algorithm, inequality, global history, microlevel data

Work In A Globalised World. Allocation Algorithm To Add Labour Relations To Digitised Census Data

Contemporary studies on social inequality often focus on income or status attainment, but neglect the fundamental underlying relationship between employer and employee, referred to as a 'labour relation'. This negligence of labour relations (for and with whom one works) was for a long time of no concern, as the employer-employee relationship was predominant in the period after World War II. However, the current fierce debate on the desirability of precarious work among the rising number of freelancers and independent contractors around the world, as well as the increased media attention and consumer awareness of 'forced labour', shows that employer-employee relationship is not a universal constant, but the result of a much broader historical context. Moreover the interest in the historical context of social inequality is now bigger than ever, judging by both the academic and media impact of recent publications (e.g. Clark, 2014; Piketty and Goldhammer, 2014; van Zanden et al., 2014).

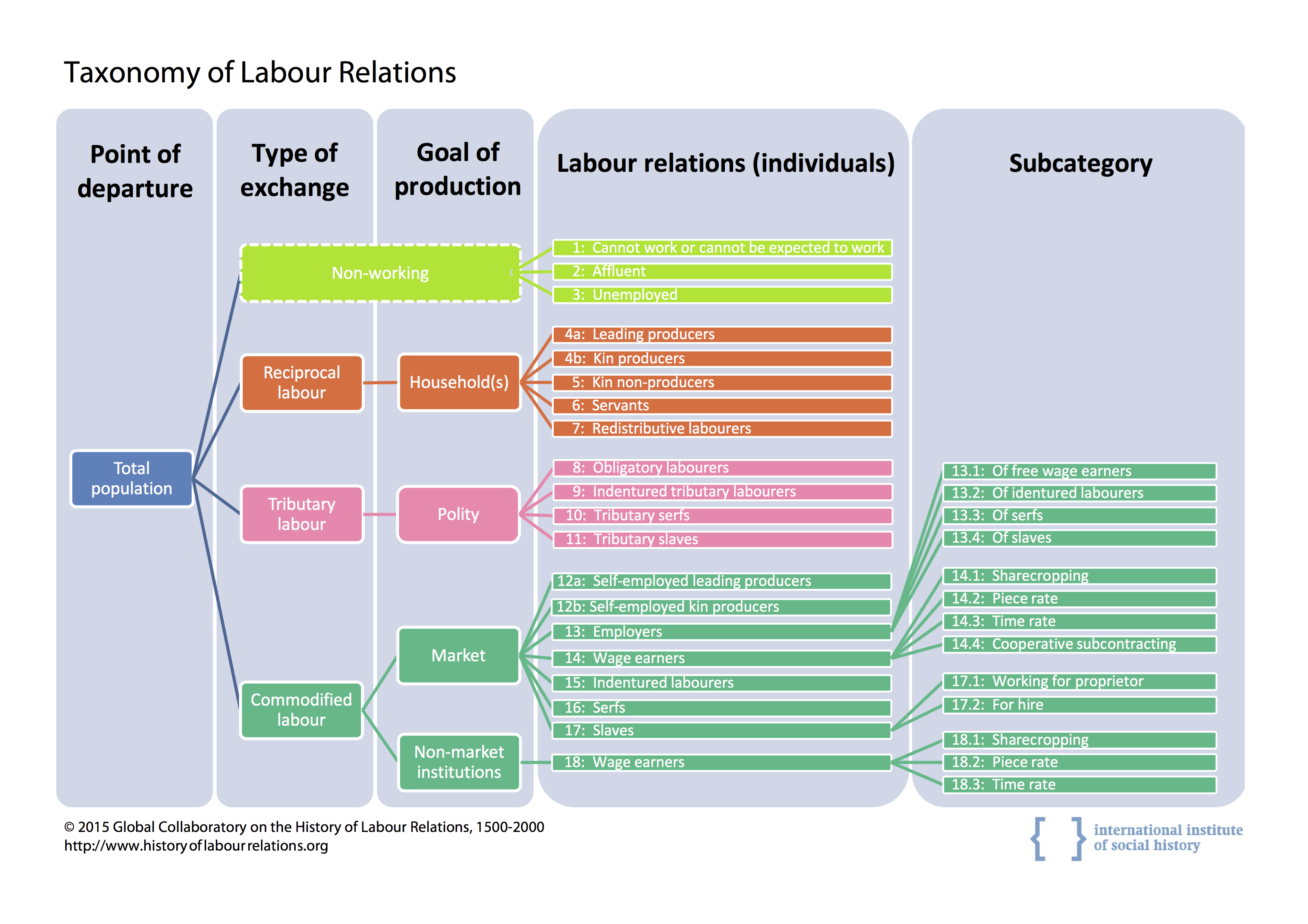

In order to describe and explain the historical context of shifts in labour relations and to recognize global connections between these shifts, a taxonomy of labour relations covering the past five centuries was devised by the participants of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations (https://collab.iisg.nl/web/LabourRelations/; Figure 1). This collaboratory – hosted by the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam (http://www.socialhistory.org) – has grown in the past decade to an online scholarly community of dozens of regional experts across the world and from various scholarly disciplines, such as social and economic historians, archaeologists and sociologists.

Using the taxonomy (Lucassen, 2013) (Figure 1), accompanying codebook and guidelines for data entry, the global collaboratory has gathered data on labour relations for more than twenty countries, using five temporal cross-sections (1500, 1650, 1800, 1900, [Africa: 1950], 2000) (Brown and van der Linden, 2010; Hofmeester and Moll-Murata, 2011; van der Linden, 2008; Lucassen, 2008). Databases of many more countries and regions are currently being prepared. For each country and cross-section a set of scholarly products are created that consists of a predesigned database with 1) population and demographic data and 2) details of the labour relations. A methodological paper explaining the choices made in the data collection for each country and time period accompanies the database. Both the database and methodological paper are verified before they are provided online as open access publication.

Until now, most of the data gathered are manually derived from aggregated sources, similar to contemporary occupational censuses, mainly for the period before 1800. The main aim of this paper is to present an alghorithm that was developed to automatically derive labour relations from digitized census materials. We therewith improve on the traditional way of working in the following ways. First, our alghorithm specifically applies to the biggest two projects that digitize census materials in the world NAPP and IPUMS, therewith providing a major contribution to the collection of labour relations for the post 1800 period and for the entire world.

A second advantage of the algorithm is that it provides the first alternative derivation of labour relations and thus can be used to test the reliability of the traditional derivation of labour relations. For many of the digitized censuses both original aggregated tables as well as the individual level data have been preserved, thus allowing for a reliability test of both methods.

The third advantage our algorithm provides is that is able to derive labour relations from individual level census data, thus allowing for more rigorous tests of hypotheses on labour relations. For until now, labour relations have just been gathered from aggregated census tables, only allowing for national comparisons and hypothesis testing. Also labour relations for the past two centuries have only been gathered for three cross-sectional years, while census data is available by decade from ca. 1850 onwards. By being able to attach labour relations to individuals, for the first time descriptive results on heterogeneity of labour relations within countries as well as over time will become available. Moreover, researchers will be much more able to zoom in on the characteristics related to changes in labour relations, such as individual characteristics (e.g. age, gender, education), household composition (e.g. extended family, sibling composition), and historical context of the municipality, region or state (e.g. level of development, political orientation) and therefore be able to provide more rigorous tests of hypotheses on changes in labour relations.

For this purpose, an algorithm is created to allocate labour relations to each of the millions of individual records that are part of the IPUMS databases. This algorithm was first tested on the censuses of the United States between 1850 and 2010. While an earlier version was written in R, the current algorithm was written in SPSS syntax, a fourth generation programming language, as SPSS proved to be better equipped for our purpose and to handle the large file sizes (4-10 GB). In the end, the algorithm will be available to all users of the IPUMS databases.

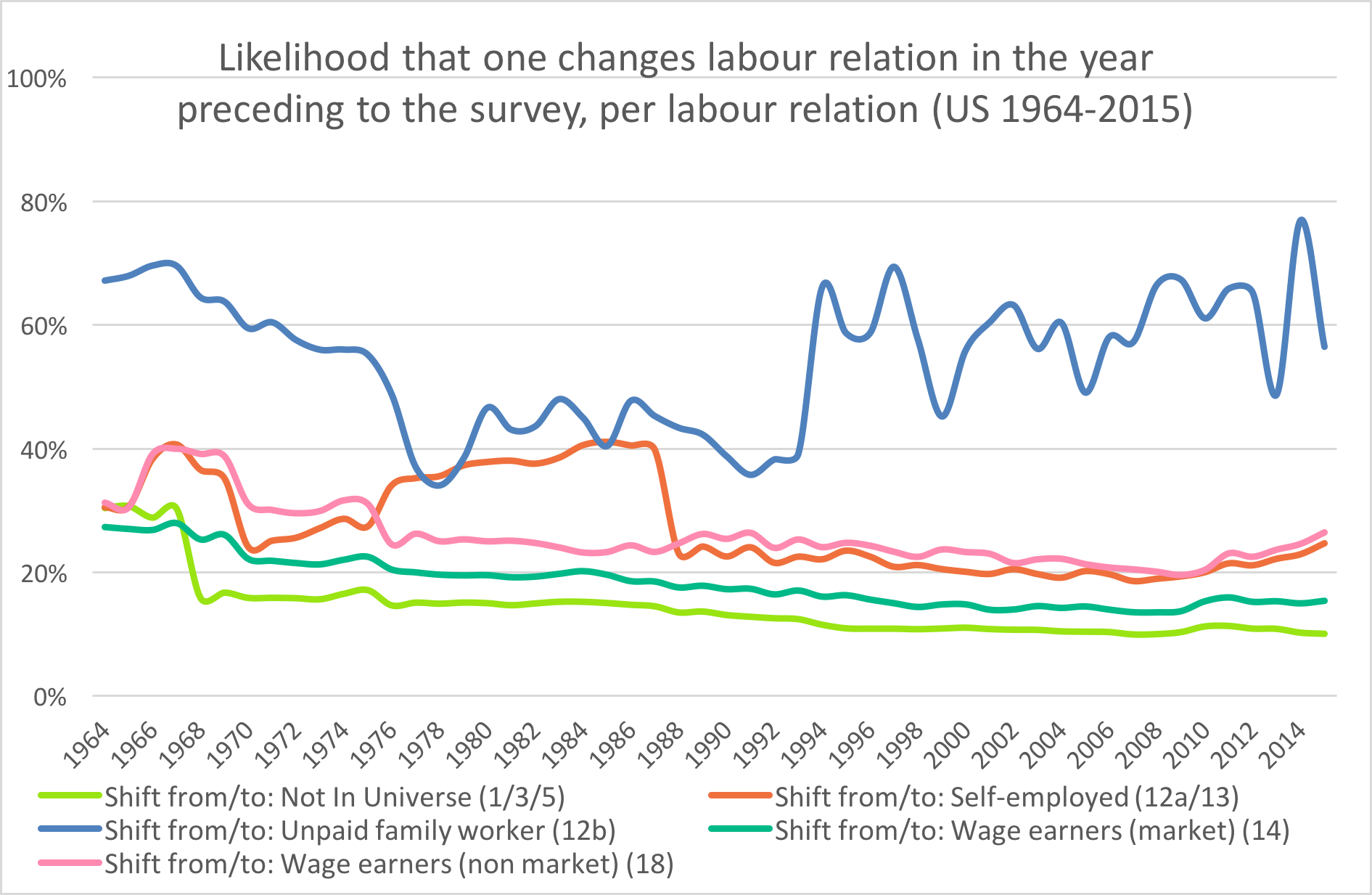

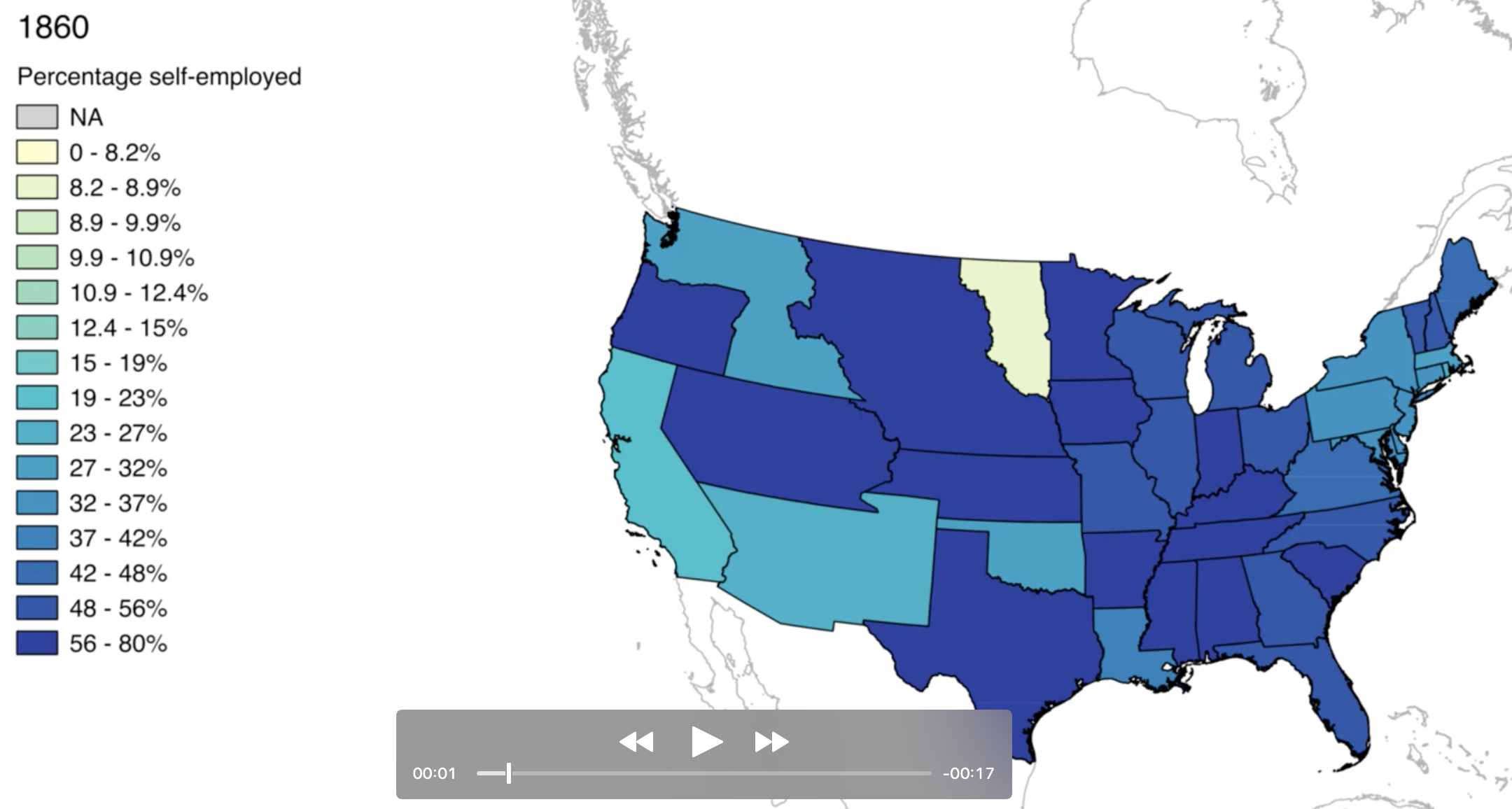

Starting from the total population, in each iterance a proportion of the records was allocated to a certain labour relation until all records were assigned. Different variables were used or combined, including age, class of worker, employment status, whether someone was considered in the labour force, their occupation, whether they lived on a farm. Here, the order of the different allocations is very important. Broadly speaking, the algorithm moves from the general to the detail. The end result is an enormous database of labour relations, both in the United States and the wider world. This allows us to study shifts in labour relations in much more detail than before (for example: Figure 2). As the census also includes numerous other information, including for instance place of residence, it is also possible to study in great detail geographical factors (Figure 3, or the role of education, gender, age, ethnicity, household composition, migrant status, wealth, and many other things.

Although the IPUMS project has done much effort already to harmonise the different census data, and although historical census takers were also much aware of the need to create uniform censuses both national and trans-national, the algorithm can easily be adapted to the specifics of each of the sources used by the Collaboratory. This means that changes in categories in the census, but also changes in the meaning of census category labels can be adapted to. A future goal is to create an updated version of the algorithm, that allows not only an allocation of a labour relation, but also provides a certainty value. This update is expected in the coming months. Also, in our paper, in addition to presenting the algorithm itself, we will provide a complete research cycle for the US census data from 1850-2013. We start by deriving the labour relations for each of the census years and show our census-specific adaptations of the algorithm to account for historic changes in census taking, such as changes in instructions or the meaning of census category labels. Next, we will describes shifts in labour relations in the US for the period under study using amongst others animations as depicted in Figure 3. Finally, we will derive and test hypotheses on acts that affect self-employment in the US, such as the Midwives Act, that forced women out of self-employment.

- Brown, C. and Linden, M. van der. (2010). Shifting Boundaries between Free and Unfree Labor: Introduction. International Labor and Working-Class History, (78), pp.4–11.

- Clark, G. (2014). The Son Also Rises. [online] Princeton University Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhrkm.

- Hofmeester, K. and Moll-Murata, C. (Eds.). (2011). The joy and pain of work: global attitudes and valuations, 1500-1650. International review of social history. Cambridge: [Published for the Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis] Cambridge University Press.

- Linden, M. van der. (2008). Workers of the world: essays toward a global labor history. Studies in global social history. Leiden ; Boston: Brill.

- Lucassen, J. (Ed.). (2008). Global labour history. International and comparative social history. Bern ; New York: Peter Lang.

- Lucassen, J. (2013). Outlines of a history of labour. (51), pp.5–46.

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. [online] Harvard University Press. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wpqbc>.

- Van Zanden, J.L., Baten, J., Mira d’Ercole, M., Rijpma, A. and Timmer, M. (Eds.). (2014). How was life? Global Well-being since 1820. OECD Publishing.