Authors: Jyi-Shane Liu, Ching-Ying Lee, Ke-Chih Ning

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: Linguistic modality, corpus evaluation, rhetorical context, historical event

Evaluating Modal Use in News Corpus for Constructing Rhetorical Context of Historical Event

1. 1. Introduction

Language use performs as a screen or filter to reality, reflecting speakers’ perception and organization of the world around them (Wardhaugh, 2002). In language, modality deploys various kinds of meaning filter (types of modal expression) which variously color and modify our conceptualizations of the world and enable us to represent it with such purposeful diversity (Hoye, 2005). Modality acts as stance-taking or attitudinal qualifications, e.g. necessity (must, should) and possibility (can, may), expressing the speaker’s opinion of a proposition or a predicate and its subject. Simon-Vandenbergen (1997) shows that modal certainty is an important feature of the discourse of political speakers and give a functional explanation of modal selections in political interviews. Garzone (2013) conducts a corpus-based study to show the decline in the use of “shall” in U.K. legislative texts and the use of other modal/non-modal substitutes for the somewhat offensive “shall.” In this paper, we examine modality use in a corpus of historical news to observe the rhetorical stance of government propaganda at a time of governance crisis. The results indicate that a strong sense of moral persuasion and demand was manifested by significant modal use for social responsibility.

2. 2. Theoretical framework and methodology

Theoretical studies to modality include generative, cognitive-pragmatic, and typological approaches (Hoye, 2005). The central notions to linguistic modality in typological sense are possibility and necessity (Lyons, 1995). We adopt Li’s (2004) Chinese modal system which was derived from an English modality framework (van der Auwera and Plungian, 1998).

The semantic categories of the modal types and the primary Chinese modal verbs are listed below. Chinese modal verbs are poly-functional, each may indicate more than one modal senses.

- Epistemic uncertainty: estimates whether something will become a fact or not and suggests objective possibility, which corresponds to epistemic possibility. The modal verbs in Mandarin Chinese that express epistemic possibility are 能 neng2 (can), 能夠 neng2 gou4 (can), 會 hui4 (may), 可 ke3 (may), 可以 ke3 yi3 (may), 得 de2 (can).

- Epistemic probability: predicts the necessity about a finite event or state or concludes about the necessity of a current event. The modal verbs that are used to express a note of conjecture include 該 gai1 (should), 應該 ying1 gai1 (should), 要 yao4 (will), 得 dei3 (must).

- Ability: expresses subjective possibility of participant related ability, function, property, or quality. Chinese modal verbs indicating participant-internal possibility include能 neng2 (can), 能夠 neng2 gou4 (can), 會 hui4 (can), 可 ke3 (can), 可以 ke3 yi3 (can), 得 de2 (can).

- Need: concerns with subjective necessity that corresponds to need internal to the participant involved in the state of affairs. It relates to hope, intention, and interest which come to cause the ultimate action or event. The Chinese modal verbs identified for expressing need are 要 yao4 (need), 需要 xu1 yao4 (need), 須 xu1 (need), 必須 bi4 xu1 (must), and 得 dei3 (must).

- Permission and circumstantial possibility: deals with possibility out of deontic sources like rules, regulations, authority, or non-deontic objective circumstances. Chinese modal verbs that express the notional categories of permission and circumstantial possibility are: 能 neng2 (can), 能夠 neng2 gou4 (can), 可 ke3 (may), 可以 ke3 yi3 (may), 得 de2 (can).

- Obligation and circumstantial necessity: involves deontic necessity out of morality or social conventions, and non-deontic necessity out of objective situations and reasons. Modal verbs that express obligation and circumstantial necessity include 要 yao4 (must), 該 gai1 (should), 應該 ying1 gai1 (should), 應 ying1 (should), 當 dang1 (should), 應當 ying1 dang1 (should), 須 xu1 (must), 必須 bi4 xu1 (must), 得 dei3 (must).

The corpus for our investigative purpose is the 228 event Taiwanese news archive, published by the 228 Event Memorial Foundation to compile local news articles during a short period, dated from 2/28/1947 to 5/15/1947, of widespread riot after Chinese takeover of Taiwan at the end of World War Two. The current study focuses on news articles from Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News (TSSDN), controlled by the government at that time, while all private news publishers were shut down one week after the incident erupted. As a baseline benchmark, we use the Academia Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese (Sinica Corpus), designed to be a balanced collection from different areas of genre, style, mode, topic, and source (Huang and Chen, 1992). The two corpora are both Mandarin (modern Chinese) without notable language variants and are considered as comparable.

For both TSSDN and Sinica corpora, we use CKIP segmentation and part-of-speech (POS) tagging for first-line processing (Chang & Chen, 1995). The size of the TSSDN corpus is a total of 0.237 million word tokens. The Sinica Corpus (version 3.1), dated approximately from 1981 to 1997, contains a total of 5.738 million word tokens, which is about 24 times the size of the TSSDN corpus. For the purpose of comparing modal use in the TSSDN corpus and the Sinica corpus, the following procedure was used to extract and observe respective modal use distribution.

Step 1. For each word token in the list of common modal verbs, extract sentences that contain the specified word token with the POS tag of auxiliary verb.

Step 2. Rank the modal verbs by its occurrence frequency, i.e., the number of the extracted sentences for each modal verb.

Step 3. Exclude the bottom half of the list of modal verbs that show insignificant use and compare the use of significant modal verbs with both absolute frequency and normalized frequency (per million word tokens).

Step 4. For the TSSDN corpus, assess each sentence in use of a modal verb and determine its actual modal type.

Step 5. Compile the actual use frequency of the modal types in the TSSDN corpus.

Step 6. Compile the top five verb semantics following the use of each modal verb for observing the association of modal sense and semantic notion.

3. 3. Results and discussion

An initial frequency observation on the list of common modal verbs in the TSSDN corpus is shown in Table 1. This led us to focus on the top half of the modal verbs that are clearly of more significant use in the investigated corpus.

Table 1. Rank list of common modal verbs by frequency in TSSDN corpus

| Rank 1 ~ 4 | Rank 5 ~ 8 | Rank 9 ~ 12 | Rank 13 ~ 16 |

| 應 ying1 (should) 535 | 可以 ke2 yi3 (can, may) 206 | 會 hui4 (may, can) 77 | 應當 ying1 dang1 (should) 21 |

| 要 yao4 (will, must) 476 | 須 xu1 (must) 170 | 得 de2, dei3 (can, must) 69 | 能夠 neng2 gou4 (can) 13 |

| 可 ke3 (can, may) 416 | 應該 ying1 gai1 (should) 138 | 需要 xu1 yao4 (need) 68 | 該 gai1 (should) 11 |

| 能 neng2 (can) 403 | 必須 bi4 xu1 (must) 123 | 當 dang1 (should) 66 | 需 xu1 (need) 6 |

Table 2 compares the use of major modal verbs in TSSDN corpus, Sinica corpus, and the newspaper subset of Sinica corpus (29.4% of the whole corpus). It is observed that TSSDN corpus shows a considerable frequency variation of modal verb use when compared with Sinica corpus and its newspaper subset. Among the eight modal verbs, three pairs of modal verbs are actually variants of each other and may be aggregated to better represent the semantic notions of the modal verbs.

Table 2. Benchmark comparison of modal verbs use

| Modal Verbs | TSSDN corpus | Sinica corpus | Increase Ratio | Sinica corpus Newspaper subset | Increase Ratio | |||

| Absolute Frequency | Normalized Frequency | Absolute Frequency | Normalized Frequency | Absolute Frequency | Normalized Frequency | |||

| 應 ying1 (should) | 535 | 2257.4 | 3250 | 566.4 | 398.5% | 1228 | 728.6 | 309.8% |

| 要 yao4 (will, must) | 476 | 2008.4 | 15783 | 2750.7 | 73.0% | 3135 | 1860.2 | 108.0% |

| 可 ke3 (can, may) | 416 | 1755.3 | 8318 | 1449.7 | 121.1% | 2439 | 1447.2 | 121.3% |

| 能 neng2 (can) | 403 | 1700.4 | 10867 | 1893.9 | 89.8% | 3038 | 1802.6 | 94.3% |

| 可以 ke2 yi3 (can, may) | 206 | 869.2 | 9546 | 1663.7 | 52.2% | 1981 | 1175.4 | 73.9% |

| 須 xu1 (must) | 170 | 717.3 | 786 | 137.0 | 523.6% | 237 | 140.6 | 510.1% |

| 應該 ying1 gai1 (should) | 138 | 582.3 | 2787 | 485.7 | 119.9% | 522 | 309.7 | 188.0% |

| 必須 bi4 xu1 (must) | 123 | 519.0 | 3181 | 554.4 | 93.6% | 788 | 467.6 | 111.0% |

In Table 3, we aggregate three pairs of modal verb variants of the same semantic notion and re-calibrate the relative amount of modal use in the two corpora and one sub-corpus. The comparison shows that the use of應 ying1, 應該 ying1 gai1 (should) and須 xu1, 必須 bi4 xu1 (must) in TSSDN corpus are significantly frequent than in Sinica corpus and its newspaper sub-corpus, while the use of the other modal verbs are somewhat comparable. This indicates that TSSDN corpus contains a strong attitude and stance through the unusual emphasis of should and must.

Table 3. Benchmark comparison of modal verbs use in semantic notions

| Modal Verbs | TSSDN corpus | Sinica corpus | Increase Ratio | Sinica corpus Newspaper subset | Increase Ratio | |||

| Absolute Frequency | Normalized Frequency | Absolute Frequency | Normalized Frequency | Absolute Frequency | Normalized Frequency | |||

| 應 ying1, 應該 ying1 gai1 (should) | 673 | 2839.7 | 6037 | 1052.1 | 269.9% | 1750 | 1038.4 | 273.5% |

| 可 ke3, 可以 ke2 yi3 (can, may) | 622 | 2624.5 | 17864 | 3113.3 | 84.3% | 4420 | 2622.6 | 100.1% |

要 yao4 (will, must) | 476 | 2008.4 | 15783 | 2750.7 | 73.0% | 3135 | 1860.2 | 108.0% |

| 能 neng2 (can) | 403 | 1700.4 | 10867 | 1893.9 | 89.8% | 3038 | 1802.6 | 94.3% |

| 須 xu1, 必須 bi4 xu1 (must) | 293 | 1236.3 | 3967 | 691.4 | 178.8% | 1025 | 608.2 | 203.3% |

Next, we observe how the use of modal verbs is distributed in the modal system to depict various aspects of attitude and stance. Each occurrence of a modal verb in a sentence is categorized in modal type by independent coders. Disputed codes are discussed to reach consensus decision. Table 4 breaks down the occurrence of modal type expression by the poly-functional modal verbs. The results reveal an extremely high concentration on the modality type of obligation, signaling a heavy dose of demand and persuasion of social responsibility from government propaganda.

Table 4. Frequency distribution of modal type expression by modal verbs

| Modal Type by Modal Verb | Epistemic uncertainty | Epistemic probability | Ability | Need | Circumstantial possibility | Circumstantial need | Permission | Obligation |

| 應 ying1, 應該 ying1 gai1 (should) | 11 | 15 | 647 | |||||

| 可 ke3, 可以 ke2 yi3 (can, may) | 112 | 97 | 248 | 165 | ||||

| 要 yao4 (will, must) | 27 | 74 | 33 | 342 | ||||

| 能 neng2 (can) | 8 | 168 | 138 | 89 | ||||

| 須 xu1, 必須 bi4 xu1 (must) | 3 | 77 | 213 | |||||

| Absolute Frequency | 120 | 38 | 265 | 77 | 386 | 125 | 254 | 1202 |

| Normalized Frequency | 506.3 | 160.3 | 1118.1 | 324.9 | 1628.7 | 527.4 | 1071.7 | 5071.7 |

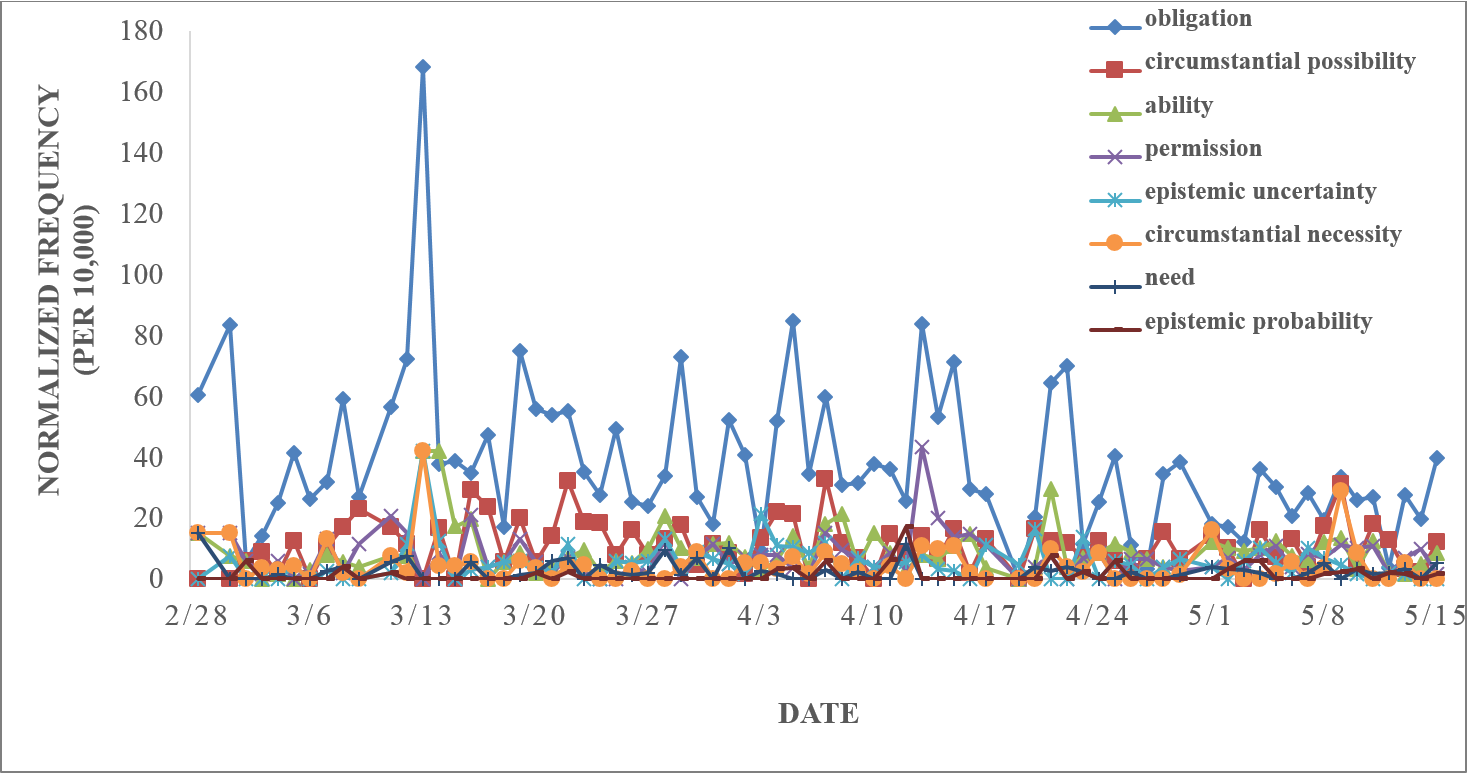

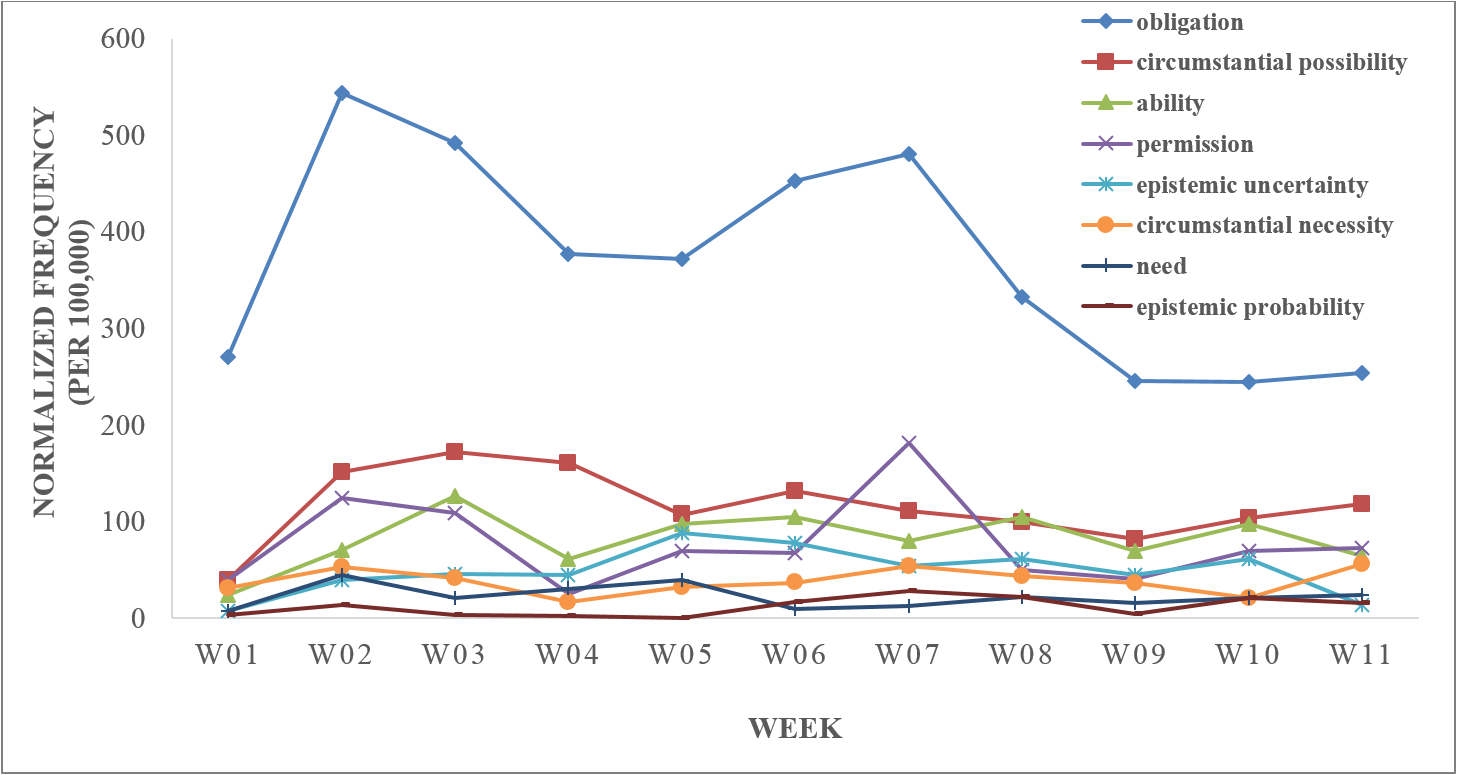

We also observe the normalized occurrence with respect to word count of news reports on a daily timeline in Figure 1 and weekly timeline in Figure 2. The temporal variation depicts a process of employing the rhetoric of obligation that immediately peaks in the second week, followed by a lower peak in the seventh week before gradually reduced in the third month, over the period in which social order was lost and regained, social activities was disrupted and restored.

Table 5 compiles the top five verb semantics, ranked by the occurrence frequency and ratio, associated with the use of each modal verb in a sentence. This helps provide a better rhetorical picture of what is being said, appealed, urged, or even warned. Overall, we observe a rhetoric sense of strict attitude and firm stance on exercising and restoring control of social order.

In conclusion, our study seems to indicate that modality is an effective linguistic feature for extracting narrative stance and provides a convenient contextual view of a corpus. Our future work includes examining more comprehensive modal expression and evaluating against corpora of various historical context.

Table 5. Primary verb semantics following modal verbs

| Modal Verb | Top Five Verb Semantics with Occurrence Frequency and Ratio | Semantic Meaning |

| 應 ying1, 應該 ying1 gai1 (should) | 注意 zhu4 yi4 (33) (4.9%) 遵守 zun1 shou3, 遵照 zun1 zhao4 (27) (4.0%) 負責 fu4 ze2 (27) (4.0%) 處分 chu3 fen4, 嚴懲 yan2 cheng3 (27) (4.0%) 檢查 jian3 cha2, 調查 diao4 cha2 (25) (3.7%) | heed comply responsible punish inspect |

可 ke3, 可以 ke2 yi3 (can, may) | 說 shuo1, 知 zhi 1(63) (10.1%) 恢復 hui1 fu4, 穩定 wen3 ding4 (45) (7.2%) 實現 shi2 xian4, 達成 da2 cheng2 (36) (5.8%) 運輸 yun4 shu1, 通行 tong1 xing2 (32) (5.1%) 報告 bao4 gao4, 提請 ti2 qing3 (26) (4.2%) | speak, know restore, stabilize achieve transport, pass report, submit |

要 yao4 (will, must) | 知道(zhi1 dao4), 認識(ren4 shi4) (64) (13.4%) 努力 nu3 li4, 加強 jia1 qiang2 (34) (7.1%) 說明 shuo1 ming2 (21) (4.4%) 檢舉 jian3 ju3, 糾正 jiu1 zheng4 (17) (3.6%) 負責 fu4 ze2 (14) (2.9%) | know, perceive strive, strengthen explain report fault, correct responsible |

能 neng2 (can) | 了解 le3 jie3, 明瞭 ming2 liao3 (39) (9.7%) 恢復 hui1 fu4 (24) (6.0%) 實現 shi2 xian4, 達成 da2 cheng2 (22) (5.4%) 解決 jie3 jue2, 克服 ke4 fu2 (19) (4.7%) 看懂 kan4 dong3, 讀寫 du2 xie3 (16) (4.0%) | understand restore achieve solve, overcome read/write |

須 xu1, 必須 bi4 xu1 (must) | 登記deng1 ji4, 註冊zhu4 ce4 (12) (4.1%) 持有 chi2 you3 (12) (4.1%) 注意 zhu4 yi1 (11) (3.8%) 懲辦 cheng2 ban4, 處分chu3 fen4 (8) (2.7%) 肅清 su4 qing1, 鎮壓zhen4 ya1 (7) (2.4%) | register carry (valid permit) heed punish exterminate, suppress |

- Chang, L. P. and Chen, K. J. (1995). The CKIP part-of-speech tagging system for modern Chinese texts. Proceedings of ICCPOL'95. Hawaii, U.S.A.

- Garzone, G. (2013). Variation in the use of modality in legislative texts: Focus on shall. Journal of Pragmatics,57: 68-81.

- Hoye, L. F. (2005). “You may think that; I couldn’t possibly comment!” Modality studies: Contemporary research and future directions. Part I. Journal of pragmatics, 37(8): 1295-321.

- Huang, C. R. and Chen, K. J. (1992). A Chinese corpus for linguistics research In Proceedings of the 1992 International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING-92). Nantes, France, pp. 1214-17.

- Li, R. Z. (2004). Modality in English and Chinese: A Typological Perspective. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Antwerp.

- Lyons, J. (1995). Linguistic Semantics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Simon-Vandenbergen, A. M. (1997). Modal (un)certainty in political discourse: A functional account. Language Sciences, 19(4): 341-56.

- Van der Auwera, J. and Plungian, V. A. (1998). Modality’s semantic map. Linguistic Typology, 2: 79-124.

- Wardhaugh, R. (2002). An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Blackwell Publishing.