Authors: Glenn Roe, Clovis Gladstone, Robert Morrissey, Mark Olsen

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: big data, sequence alignment, commonplaces, eighteenth century studies, print culture

Digging into ECCO: Identifying Commonplaces and other Forms of Text Reuse at Scale

1. Background

Commonplaces are a particular instance of historical text reuse (Dacome, 2004; Allan 2010; Blair, 2011). This paper describes our efforts at identifying commonplaces in the Gale-Cengage Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) database. Given the size of this collection, as well as the state of the data in terms of its OCR output, identifying shared passages that exhibit the textual characteristics of commonplaces – e.g., are relatively short, repeated, and rhetorically significant – is a non-trivial computational task. In our previous work on text reuse, we came across numerous examples of textual borrowings and shared passages that we considered possible commonplaces (Allen et al., 2010; Horton et al., 2010; Roe, 2012). We expanded this work into a Digging into Data Round 3 project using similar methods to explore the more than 200,000 works contained in ECCO, a dataset that represents most of the printed literary and scientific output in Britain from 1700 to 1799 1.

Previously we developed a sequence alignment algorithm for the identification of large-scale text reuse 2. This algorithm, called PhiloLine, generates a list of similar passages (based on a set of flexible matching parameters) shared between any two texts. This simple approach allows us to find borrowings and other instances of text reuse, from quotations to uncited passages and paraphrases, over large heterogeneous corpora (Edelstein et al., 2013). Historical text reuse detection is a burgeoning field within the digital humanities, whether focussed on literary allusion (Coffee et al., 2012; Coffee et al., 2014), paraphrase (Büchler et al., 2011), influence (Büchler et al., 2014), or networks of reprinting (Smith et al., 2015). While all these projects address text reuse in slightly different ways, the flexibility and scalability offered by PhiloLine, coupled with our familiarity with the system, offered significant advantages over other approaches. We thus aimed to use PhiloLine to compare the ECCO corpus to itself, compile a list of the most frequent shared passages, and from there evaluate these passages in order to build a database of potential commonplaces.

2. Eliminating duplicates

The scope and scale of the ECCO dataset represented a major hurdle both in terms of computational expense and evaluation of the matching algorithm. Faced with more than 32 million pages of text, any manipulation of the data takes on significant proportions. To put this in perspective, comparing ECCO’s 200,000 documents to each other means making some 40 billion pairwise comparisons and then storing and evaluating the output. Fortunately, our focus on commonplaces requires us to dramatically reduce the number of comparisons. We needed, for instance, to eliminate duplicate or near-similar texts in order to reduce the number of documents for comparison. The most obvious method would be to compare all the words in each work, and define a similarity threshold beyond which we consider two works to be the same. But, given the unequal quality of the OCR in the ECCO dataset, the reliability of any algorithm meant to detect similarity between two texts is very low. Two identical texts, for instance, can potentially only share 20% of individual tokens due to the quality of the OCR. As a result, we decided to focus our efforts on comparing document metadata instead, as it is of excellent quality.

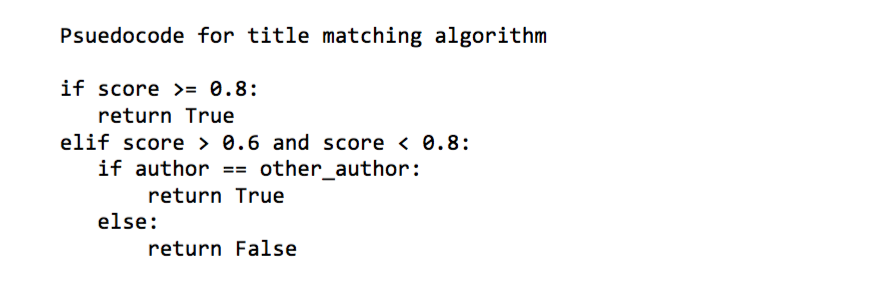

Our methodology consisted in comparing titles in the dataset using a cosine similarity algorithm (Singhal, 2011). For our purposes, we determined a minimal similarity index to automatically determine whether two texts were the same, that is to say a re-edition of the same work. Beyond a certain threshold score, the newest document in terms of date of publication is automatically flagged as a duplicate. If it so happens that the minimal score is not reached, but still remains high, we compare authors, and if these are the same, we similarly flag the most recent document as a duplicate:

The document with the oldest publication date serves as the “source” text. Using this method, we were able to reduce the size of the corpus by 43%, eliminating 88,850 documents. We were thus left with 116,700 unique texts on which to run our matching algorithm.

3. Detecting similar passages

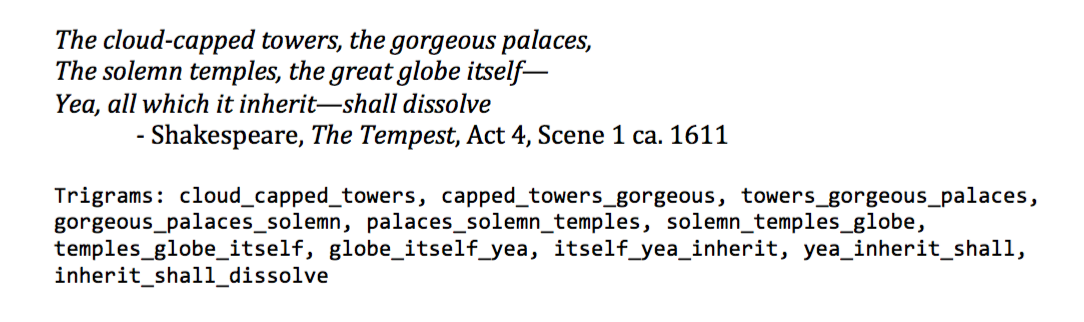

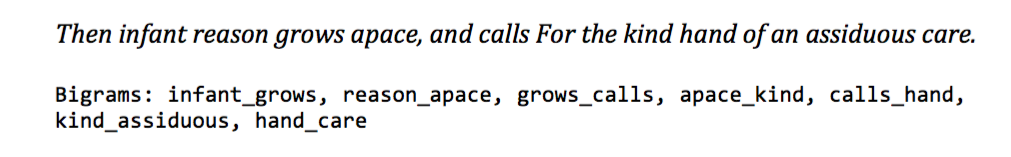

Similar passage detection requires a one-to-one document comparison. Rather than compare all 116,700 texts to one another, we decided to leverage Gale’s thematic divisions, and limit the comparison task to individual modules 3. While PhiloLine’s matching capacity is powerful, it is necessary to understand its underlying algorithm in order to configure the tool properly. Briefly, PhiloLine’s operational logic is to compare sequences of words, or n-grams, and determine the presence of a shared passage according to the number of common contiguous n-grams between two sequences. For example, the following text from Shakespeare’s The Tempest is rendered by as a set of overlapping n-grams (where n = 3):

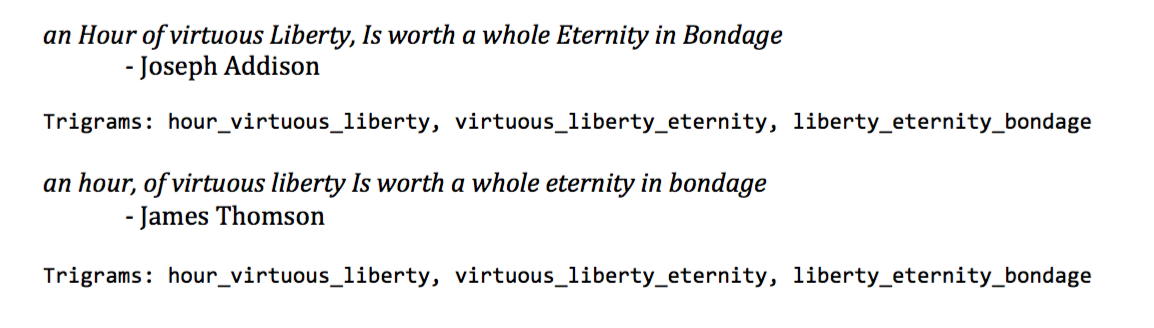

Trigram generation and stopword removal are thus the main parameters we apply to transform texts prior to the sequence alignment process. Once this is done, we proceed with the text-sequence comparisons. Below is an example of just such an alignment of sequences drawn from the Literature and Language module:

In this case, we note the perfect alignment, which PhiloLine detected because there are at least three contiguous trigrams in common between both passages.

Using these base parameters (overlapping trigrams with stopwords removed), we compared the ECCO corpus to itself on a module-by-module basis. The output of this comparison ranged from 3.5 million common passages in the Literature and Language module, to almost 17 million possible commonplaces in Religion and Philosophy. Identifying these common passages is thus only a first step. Even after significant duplicate reduction, the sheer scale of the passages that require post-processing evaluation is daunting.

4. From similar passages to commonplaces

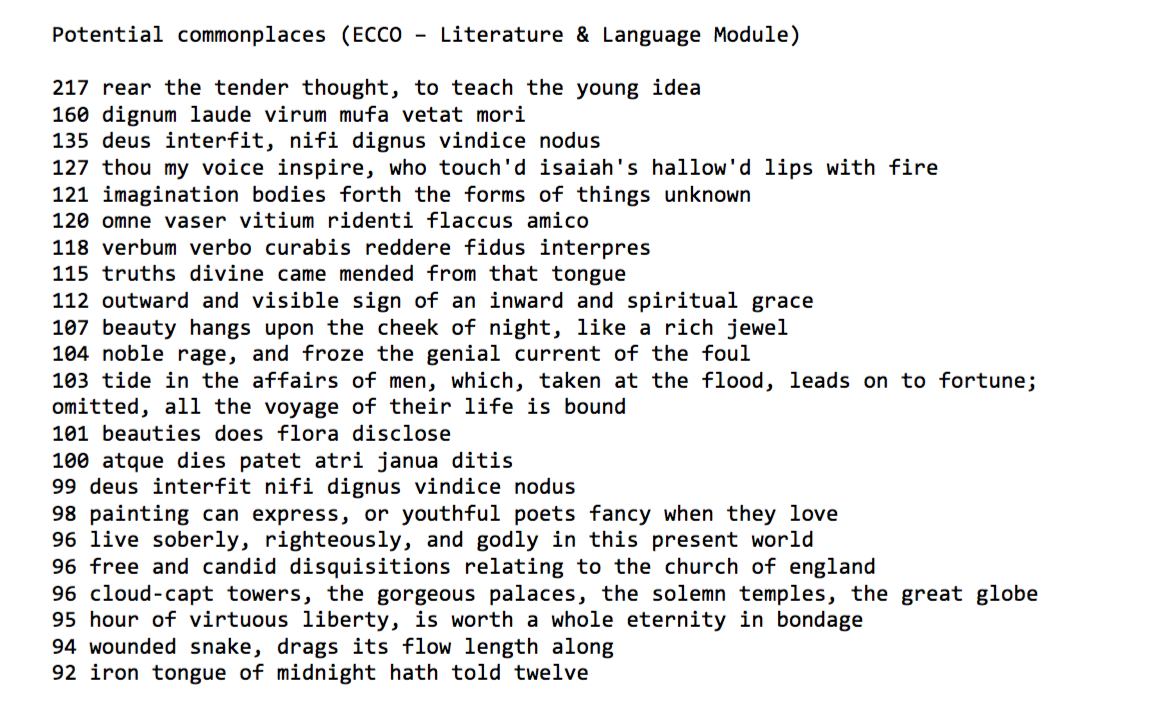

To attack this problem, we treat commonplaces generically as the repeated use of the same passage - more or less similar - in a minimum number of different authors. We began by grouping all source passages that were identical in order of frequency. Given that commonplaces are normally short expressions, at the most no longer than several sentences, we restricted our search to passages containing a minimum of five words and a maximum of 75:

A cursory glance at this list reveals several variants of the same passage that need to be merged in order to better represent a single commonplace. If we take the following passage from the Scottish poet James Thomson, for instance:

Then infant reason grows apace, and calls For the kind hand of an assiduous care. Delightful talk! to rear the tender thought, To teach the young idea how to shoot, To pour the freft infiruAion o'er the mind, 1150 To breathe enlivening spirit, and to fix The generous purpose in the glowing breast.

We notice that the reuse of this passage in other authors can vary significantly.

Gentleman of the Middle Temple (1775):

How glorious would her matron employments be, to hear the tender thought, to teach the young idea how to Jhoot; to be at once the precept and example to her family of every thing that was good, every thing that was virtuous.

Mrs Lovechild (1790):

Happy the Mother "Distilling knowledge through the lips of “love !”- ' Delightful talk! to rear the tender thought, “To teach the young idea how to shoot”, To pour the fresh inltrution o'er the mind !'Lines which will never cease to be quoted...

Given the variability in the reuse of any given passage, as well as the approximate quality of the OCR, we developed a new algorithm that could match similar passages in a way that was both precise, and yet more flexible than PhiloLine. The algorithm uses the same n-grams as PhiloLine, though they are constructed differently. Rather than use overlapping trigrams, as we do for sequence matching, here we use alternating bigrams for increased flexibility:

By skipping a word in the creation of these bigrams, we create n-grams that are both rarer than in-sequence bigrams, but also more common than in-sequence trigrams. In essence, these bigrams are flexible trigrams where the middle word is ignored. In this manner we can alleviate some of the issues that come from the dirty OCR. As there is a higher probability for a regular trigram to contain a wrongly identified letter, it has a higher chance of being unique, therefore making it less reliable for similarity matching than our flexible trigrams.

Finally, we needed to take into account the different lengths of these passages, as some are much longer than others. This variability led to the introduction of a coefficient that accounts for varying lengths, and allows us to automatically determine the minimum number of matching n-grams needed to establish similarity between two passages. For instance, if two passages of 30 words must share 4 bigrams, a passage of 30 words and another of 50 should share more bigrams to retain the same level of similarity.

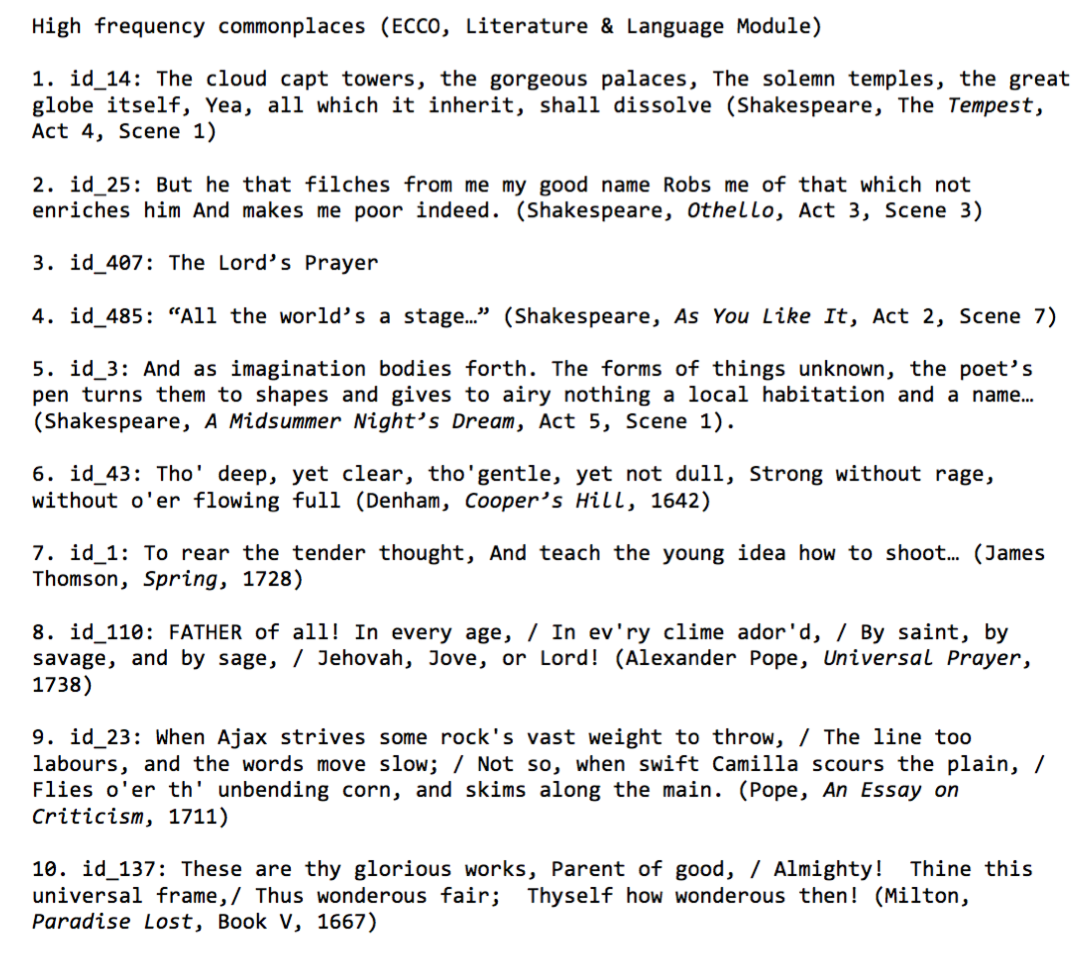

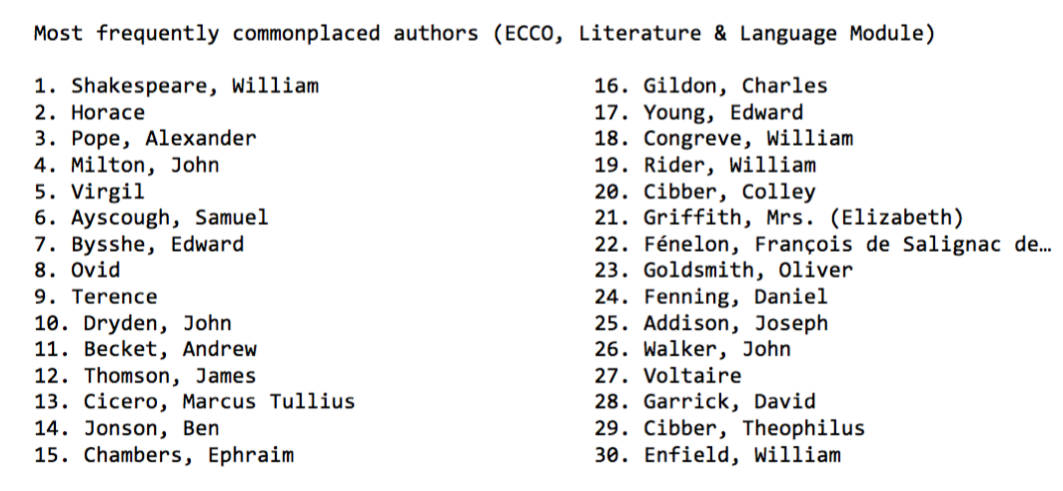

Using the above methods, we were able to merge various uses of a single source passage and assign them a unique identifier. We can therefore now identify the highest frequency commonplaces in the Language and Literature module (see Appendix 1), as well as the most ‘highly commonplaced’ authors, i.e., those that generated the most shared passages (see Appendix 2). These preliminary results suggest that commonplacing, as an intertextual reading/writing practice, was alive and well in 18th-century England. Digging into a dataset such as ECCO can thus offer us new perspectives from which to view and understand 18th-century print culture, provided we unearth more than we cover up.

5. Future Work

We aim to release an interactive database of possible commonplaces in early 2016. The database will allow users to navigate the ECCO dataset via the commonplaces, most commonly cited authors and works, and visualize commonplace use and practices over time. We will also introduce several curated datasets that pre-date the 18th century, and that can act as a control on sources that fall outside the date boundaries of our data. These possible datasets include the King James Bible, Classical Latin texts, and EEBO-TCP 4. Further goals for this project include merging the module-specific results into one large pool of potential commonplaces that reach across disciplinary boundaries; developing a user interface that allows for commonplace curation as a form of crowdsourcing; and introducing non-English datasets for comparison in order to find instances of multi-lingual commonplace practices.

Appendix 1:

Appendix 2:

- Allan, D. (2010). Commonplace Books and Reading in Georgian England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Allen, T., Cooney, C., Douard, S., Horton, R., Morrissey, R., Olsen, M., Roe, G. and Voyer, R. (2010). Plundering Philosophers: Identifying Sources of the Encyclopédie. Journal of the Association for History and Computing,13(1).

- Blair, A. (2011). Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Büchler, M., Crane, G., Mueller, M., Burns, P. and Heyer, G. (2011). One Step Closer To Paraphrase Detection On Historical Texts: About The Quality of Text Re-use Techniques and the Ability to Learn Paradigmatic Relations. Journal of the Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities and Computer Science.

- Büchler, M., Geßner, A., Berti, M. and Eckart, T. (2013). Measuring the Influence of a Work by Text Re-Use. In Dunn, S. and Mahony, S. (eds), The Digital Classicist 2013. London: University of London Institute of Advanced Studies, pp. 63-80.

- Coffee, N., Koenig, J.-P., Poornima, S., Forstall, C., Ossewaarde, R. and Jacobson, S. (2012). The Tesserae Project: Intertextual Analysis of Latin Poetry. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 28(1).

- Coffee, N., Gawley, J., Forstall, C., Scheirer, W., Corso, J., Johnson, D. and Parks, B. (2014). Modeling the Interpretation of Literary Allusion with Machine Learning Techniques. Journal of Digital Humanities, 3(1).

- Dacome, L. (2004). Noting the Mind: Commonplace Books and the Pursuit of the Self in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Journal of the History of Ideas 654: 603-25.

- Edelstein, D., Morrissey, R., and Roe, G. (2013). To Quote or not to Quote: Citation Strategies in the Encyclopédie. Journal of the History of Ideas, 74(2): 213-36.

- Horton, R., Olsen, M. and Roe, G. (2010). Something Borrowed: Sequence Alignment and the Identification of Similar Passages in Large Text Collections. Digital Studies / Le Champ numérique, 2(1).

- Roe, G. (2012). Intertextuality and Influence in the Age of Enlightenment: Sequence Alignment Applications for Humanities Research. In Meister, J.C., (ed), Digital Humanities 2012. Hamburg: University of Hamburg Press, pp. 345-47.

- Singhal, A. (2001). Modern Information Retrieval: A Brief Overview. Bulletin of the IEEE Computer Society Technical Committee on Data Engineering, 24(4): 35-43.

On our Digging into Data project, see http://diggingintodata.org/awards/2013, and on ECCO, see http://gdc.gale.com/products/eighteenth-century-collections-online/.

Gale’s ECCO modules: History and Geography (17,950 works, reduced to 10,528); Social Sciences and Fine Arts (48,335 works, reduced to 30,498); Medicine and Sciences (15,636 works, reduced to 9,202); Literature and Language (53,351 works, reduced to 25,655); Religion and Philosophy (51,485 works, reduced to 29,962); Law (13,595 works, reduced to 7,726); and General Reference (5,198 works, reduced to 3,129).