Authors: Isabella di Lenardo, Benoit Seguin, Frédéric Kaplan

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: art history, search engine, patterns, deep learning, convolutional neural networks

Visual Patterns Discovery in Large Databases of Paintings

The digitization of large databases of works of arts photographs opens new avenue for research in Art History. For instance, collecting and analyzing painting representations beyond the relatively small number of commonly accessible works was previously extremely challenging. In the coming years, researchers are likely to have an easier access not only to representations of paintings from museums archives but also from private collections, fine arts auction houses, art historian photo collections, etc. However, the access to large online databases is in itself not sufficient. There is a need for efficient search engines, capable of searching painting representations not only on the basis of textual metadata but also directly through visual queries. In this paper we explore how convolutional neural network descriptors can be used in combination with algebraic queries to express powerful search queries in the context of Art History research.

1. Context and Method

This project is part of project called Replica, conducted in collaboration with the Cini Foundation in Venice. This project is based on two parallel developments, the digitization of the Cini Foundation’s photo library, a collection of about a million photographs of paintings, engravings, plastic arts and architecture (1300 - 1900) and the creation of a dedicated search engine allowing for searches for visual patterns in this database. As the digitization is currently ongoing, the results reported in this paper are performed on a subset of only 39 000 paintings. However, the progressive densification of the database, including a large set of so-called minor painters, should, in the coming months, unfold the full discovery potential of this search engine.

The field of visual pattern recognition has been recently transformed by the surprising performances of so-called deep learning approaches using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). CNN are multi-layers architectures used for supervised learning, especially for object classification. Each layer is representing an operation on the previous layer: convolution layer, fully-connected layer, pooling layer, regularization layer, etc. These networks have many parameters (filter parameters, fully-connected weights) that can be learned via backpropagation in a supervised manner. Traditionally, the input (first) layer is a full raster image and the output (last) layer is a vector representing the score of the input image for each class. By showing the network some labeled images and comparing the network’s output to the desired label, one can update the parameters of the model.

The theory of deep neural methods have been known for decades, and were already successfully applied with the first convolutional neural networks in the 90s to digit recognition (LeCun et al., 1989). However, their computational complexity and the necessity of important amount of training data have seen them being ignored for a long time. With very large datasets available like ImageNet, and GPU computation being more accessible, there has been a sudden surge of interest in deep methods (Deng et al., 2009).

In 2012, a convolutional neural network shattered the competition in a difficult 1000 class object recognition challenge, attaining the impressive result of a top–5 error of 15.3% compared to 26.3% for the runner-up (Krizhevsky et al., 2012). Ultimately, this work had an important impact on the machine vision community starting the so-called deep learning revolution. A clear manifestation of this trend was that just a year later at the next iteration of this object recognition challenge, almost every entry was based on CNNs as well.

Despite being trained to recognize a precise set of classes. It has been observed that some of the learned parameters of the CNNs will most likely be similar across different datasets. For instance, the first convolutional layer usually learns various edge detectors and basic filters. Some researchers have evaluated the representative power of CNN trained for a specific task to other problems. Using a model that outperformed the others in 2012 on the ImageNet data, results seemed extremely promising, suggesting that task transfer is possible (Donahe et al., 2014).

To calculate the descriptors of our search engine, we use a pre-trained Convolutional Neural Networks similar to the one described in (Donahe et al., 2014). Each painting of our database is associated with 1000 features, corresponding to the last convolutional layer of the pre-trained Convolutional Neural Network. These features are thought to represent high-level characteristics directly usable for the classification tasks. Through this process each painting is associated with a single point in a high dimensional space. When a single image query is sent to the search engine, the results are simply shown, ranked by their distance to the query.

However, similarity between paintings could not be the results of single homogenous distance. To enable the users to specify the kind of similarity they want to explore, a more refined language has been introduced. Searches take the form of algebraic formulas in which the user can add or subtract examples. For performing such searches, we use a binary support vector machine (kernel Radial Basis Function). In the cases where no negative examples are provided, a one-class-support vector machine is used (in the case of a query with a single image, this corresponds to a simple nearest neighbor algorithm). The rest of the paper shows examples of such algebraic queries and the corresponding results.

2. Examples of queries and results

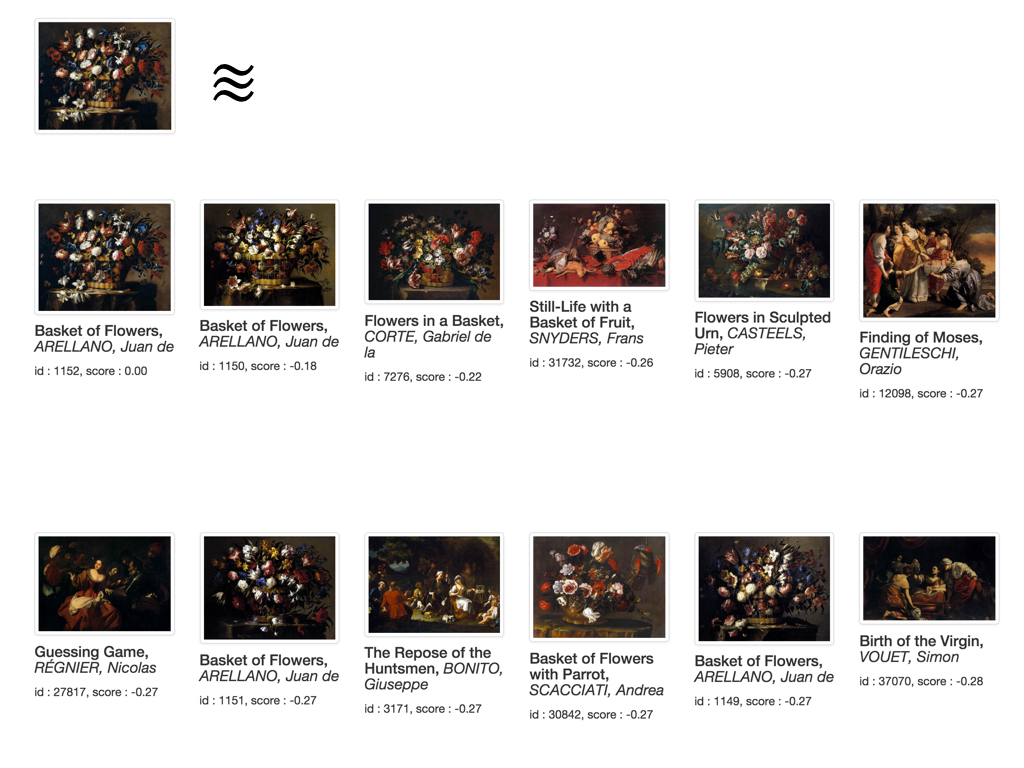

The classic principles for classifying visual similarities in Art History include various dimensions like recurrence of particular pictorial patterns or common compositional structures. As a query illustration, the first criteria of classification chosen is the search for common ‘dominant and multiple pictorial motif’ in the composition. One classic example in this typology is the Still life, featuring for instance only a large bouquet of flowers. The development of this subject has a long history, from the late sixteenth century, before arriving at its codification during the seventeenth-century. The results of a query with Juan de Arellano’s Still life of flowers (Fig. 1) include other famous interpreters of the genre, almost identical in composition and also close in terms of chronological and pictorial influences: de la Corte, Snyders, Casteels. However, there are also seventeenth-century painters, Gentileschi, Régnier, Bonito, Vouet, who, while not painting Still lifes, are characterized by the same tonality of chiaroscuro typical of this precise moment in history of art. Without further information the similarities found by a single image query include various families of resemblances combining pictorial patterns and color tones.

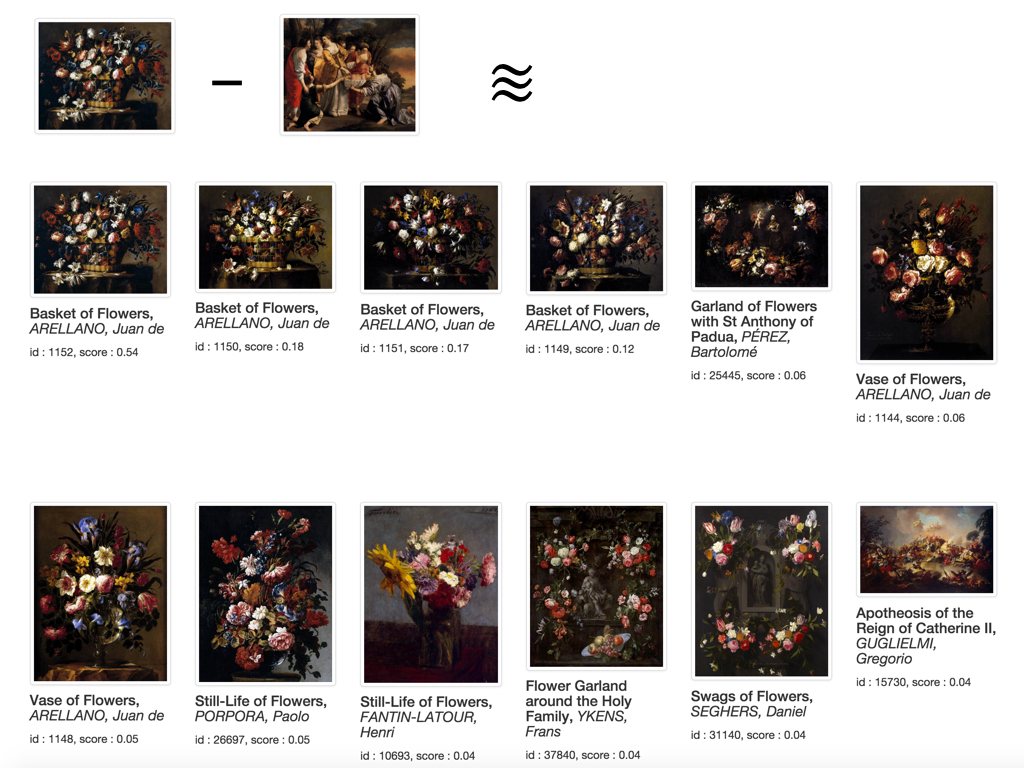

To focus only on the pictorial motif of flowers excluding any paintings with figures, we subtract one of the paintings by Gentileschi to the initial query (Fig. 2). We obtain all the ‘key painters’ in this genre including for instance Daniel Seghers. He does not paint a real Still life but flowers around a sacred figure, the Virgin, one of the first subjects, probably invented by Jan Brueghel the Elder. It is probably from this initial subject that evolves the Still Lifes with flowers. So, in this case, the algebraic query recovered the evolution of a specific pictorial motif with its significant variations during the Seventeenth century.

Another criteria of classification in Art History are structural analogies between compositions (Gombrich, 1960). Structure of the composition is understood here in a geometrical sense, with the reoccurrence of similar geometrical patterns in various paintings. The formal analysis of paintings have classically focused on such kinds of structural similarity (Focillon 1964; Didi-Huberman 1996).

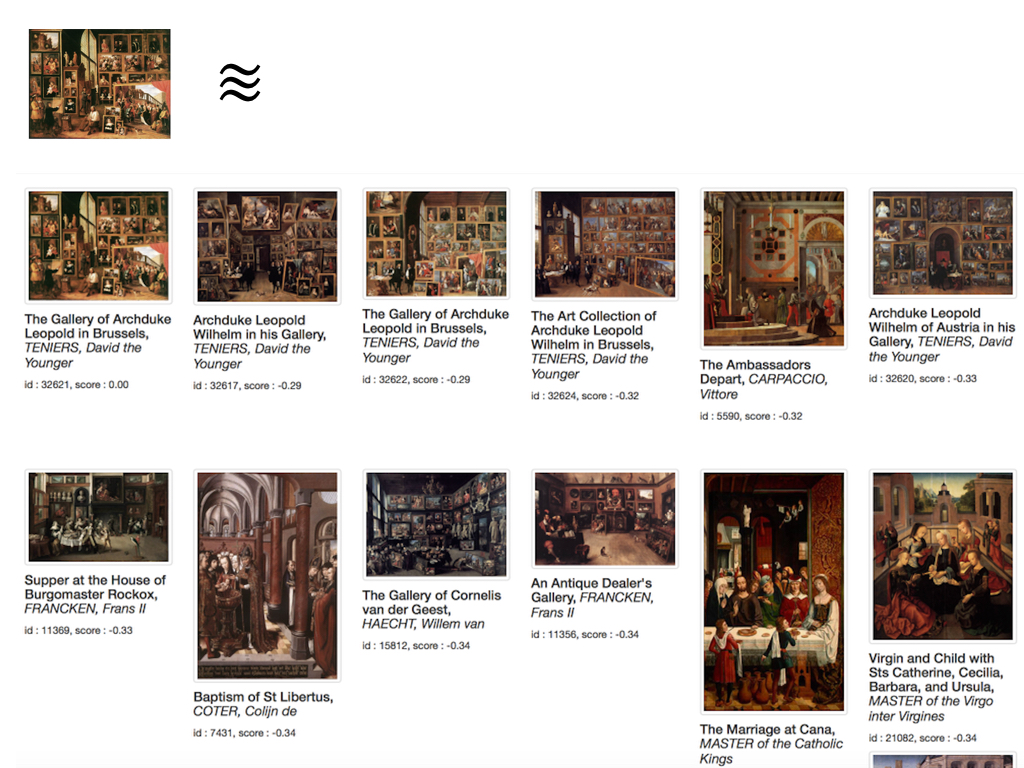

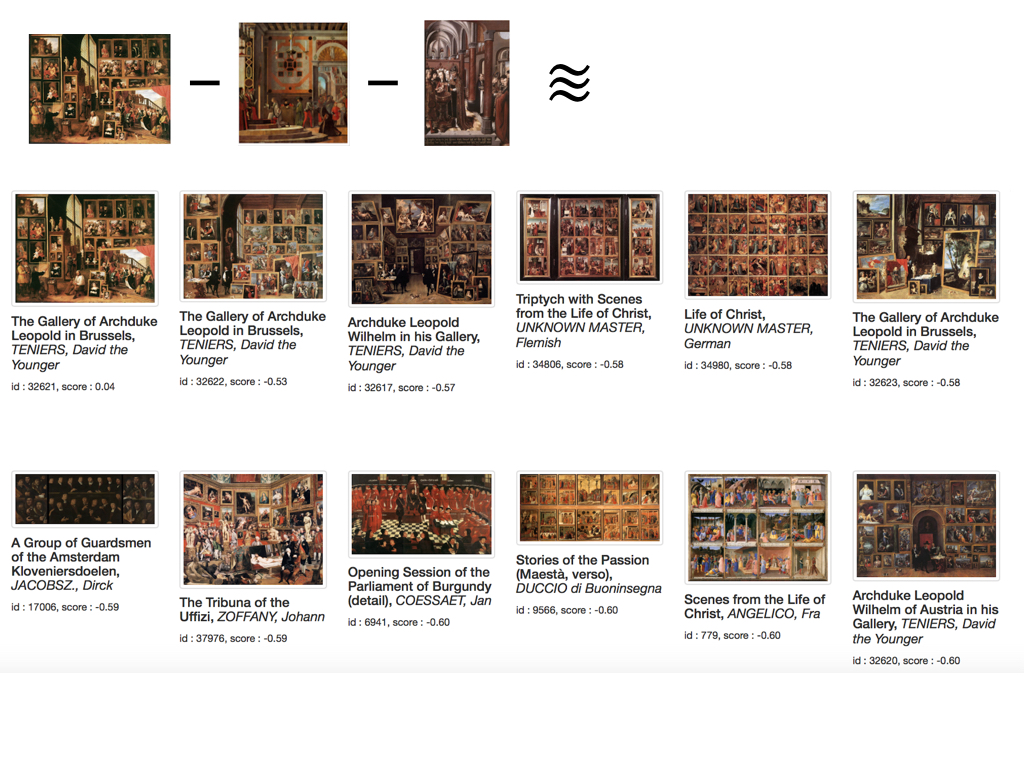

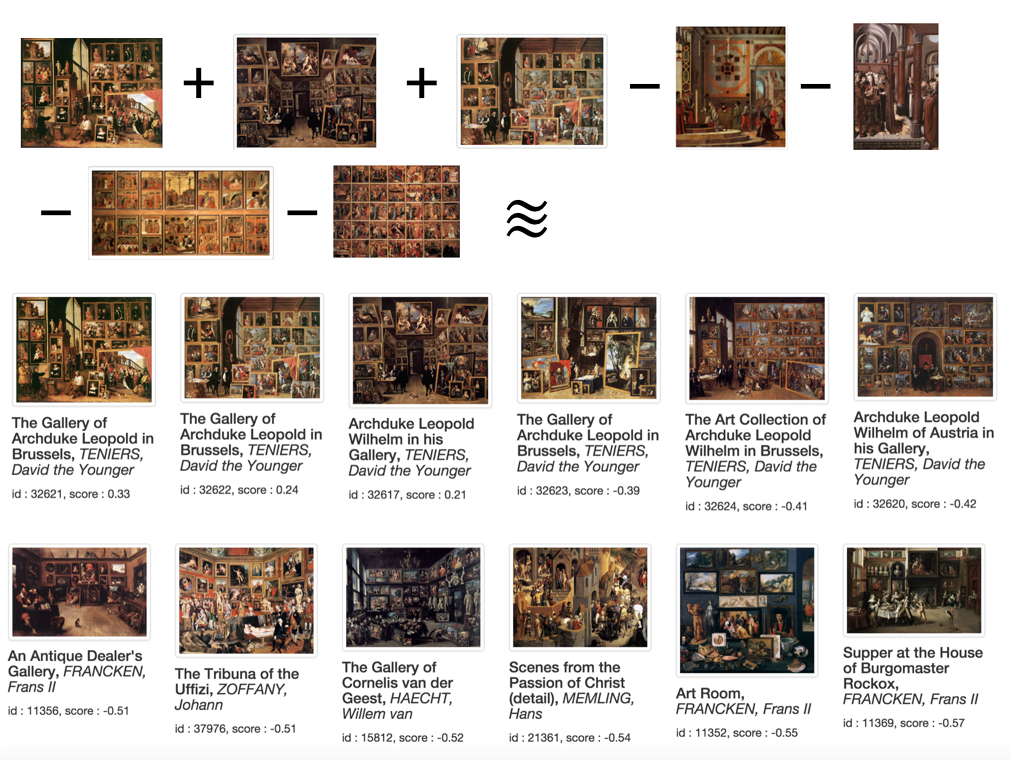

The The Gallery of Archduke Leopold painted by David Teniers the younger, in 1639, is also known to have four different variants. This painting is considered a reference of a long tradition of paintings subjects featuring cabinet of art lovers and collectors, a well studied genre (Findlen 1996; van der Veen 1993). A single query returns variations of the same painting (Staatsgalerie Schleissheim, Münich; Prado, Madrid; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien), but also painting featuring squares within squares (Fig. 3). For instance on The Ambassadors depart by Vittore Carpaccio and Baptism of St Libertus by Colijn de Coter, squares are on the floor or on the wall. To refine further our search and find the “good neighborliness” (Warnke 2000; Freedberg 1989) of David Teniers structure, we can try to exclude these two examples by subtracting them to the initial query. Results of such a query exclude now interior scenes featuring geometrical squares but now include various scenes of the Passion of the Christ organized as sequences of “squares”, non featuring any elements in perspective (Fig. 4). In a third attempt, we can now exclude those by substracting them to the initial query and reinforce the focus on search by adding variant of the first painting by Teniers. Indeed, all the first results feature now paintings with galleries of collectors with examples of the most important authors of the genre, thus facilitating the study of their mutual influence (Fig. 5).

3. Perspectives

Pattern recognition methods have made extremely impressive progresses in the recent years, thanks to the advances of convolutional neural network and the advent of very large databases of images. As Art History deals with the study of the migration of patterns, this is surely a great opportunity for designing new tools to search through large databases of paintings photographs. This paper is a first examination of the typologies of search use cases that could be envisioned combining convolutional neural network features and simple algebraic formulas. This initial study illustrates that this new way of expressing queries allows for the incremental definition of various kinds of “similarities” between paintings. Convolutional neural networks features manage to capture many dimensions of similarity between paintings, including composition, colors and also common iconographic elements. Combined with a simple language for expressing the specificity of the traits that the user looks for, it could enable new powerful search tools that may in turn have important impact on history of art studies.

- Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.-J. Li, K. and Fei-Fei, L. (2009). ImageNet:A large-scale hierarchical image database, IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit.

- Didi-Huberman, G. (1996). Pour une antropologie des singularités formelles. Remarque sur l’invention warburgienne. Genèses, 24: 145-63.

- Donahue, J., Jia, Y., Vinyals, O., Hoffman, J., Zhang, N., Tzeng, E. and Darrell, T. (2014). DeCAF:A Deep Convolutional Activation Feature for Generic Visual Recognition, Int. Conf. Mach. Learn, pp. 647–55.

- Findlen, P. (1996). Possessing Nature - Museums, Collecting & Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Reprint. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Focillon, H. (1964). Vie des formes: suivie de l’"Eloge de la main", PUF, Paris.

- Freedberg, D. (1989). The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response, Chicago-London.

- Gombrich, E. H. (1960). Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, Pantheon Books, New York.

- Krizhevsky, A. Sutskever, I. and Hinton, G. E. (2012). Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks, Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., pp. 1097–1105.

- LeCun, Y., Boser, B., Denker, J. S., Henderson, D., Howard, R. E., Hubbard, W. and Jackel, L. D. (1989). Backpropagation Applied to Handwritten Zip Code Recognition, Neural Computation, pp. 541–51.

- Van der Veen, J. (1993). Galerij en Kabinet, vorst en burger. Schilderijen Collectie in de Nederlanden, In Bergvelt, E., Meijers, D. J. and Rijnders, M. eds. Verzamelen van Rariteitenkabinet tot Kunstmuseum, Heerlen, pp. 145-64.

- Warnke, M. (2000) Aby Waburg - Der Bilderatlas. Mnemosyne, Akademie, Berlin.