Authors: Peer Trilcke, Frank Fischer, Mathias Göbel, Dario Kampkaspar

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: network analysis, literary history, small worlds, drama

Theatre Plays as 'Small Worlds'? Network Data on the History and Typology of German Drama, 1730–1930

1. Approach

Decades ago, alongside more traditional structuralist paradigms that were largely based on linguistic theorems (Lotman 1972, Titzmann 1977), literary studies began to undertake structural analyses based on empirical sociology, in particular the social network analysis. Structure was no longer solely defined by semantic relations (such as opposition or equivalence), but by social interactions, too (Marcus 1973; Stiller, Nettle and Dunbar 2003; de Nooy 2005; Stiller and Hudson 2005; Elson, Dames and McKeown 2010; Agarwal et al., 2012). In the context of the Digital Humanities, this kind of approaches has gained a new dynamic in shape of a dedicated literary network analysis (Moretti 2011; Rydberg-Cox 2011; Park, Kim and Cho 2013; Trilcke 2013). This method is based on the analysis of bigger literary corpora (i.e., quantitative data) and promises insights into the history of literature as well as generic characteristics of literary texts. In our project, "dlina. Digital LIterary Network Analysis", we already developed a workflow for the extraction, analysis and visualisation of network data from dramatic texts built on basic TEI markup (Fischer, Kampkaspar, Göbel, Trilcke, 2015). This paper will present results of our analysis of the network data gathered so far and discuss them in the light of current theories in the field of social network analysis.

2. Data Collection and Analysis

Our current corpus comprises 465 German-language dramas (from 1730 to 1930), the better part of the Digitale Bibliothek corpus contained in the TextGrid repository ( https://textgridrep.de/). The structural data crucial for the network analysis of these dramas (segmentation, character identification, etc.) was revised manually in a rule-based process to straighten out issues with the OCR and TEI tagging. We also had to level out philological peculiarities that would otherwise distort our results (such as different names for identical figures or groups of characters like 'Both' or 'All'). All the structural data is stored in an XML format we especially developed for that purpose (DLINA format). Network visualisation and network-value calculation has been automated (via Python and, alternatively, JavaScript to facilitate a direct embedding of our results into webpages). The scripts are fed with the data stored in DLINA files. In addition to graphs and simple network values that globally describe networks (like network size, density, average degree, average path length, clustering coefficent), we also calculate centrality values for the characters of each play (like degree, average distance, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality). In addition, we most recently implemented the calculation of random graphs based on the observed drama networks. All data and visualisations are freely available online on the project website ( https://github.com/dlina and https://dlina.github.io/linas/).

3. Evaluation, Part I: History of Drama

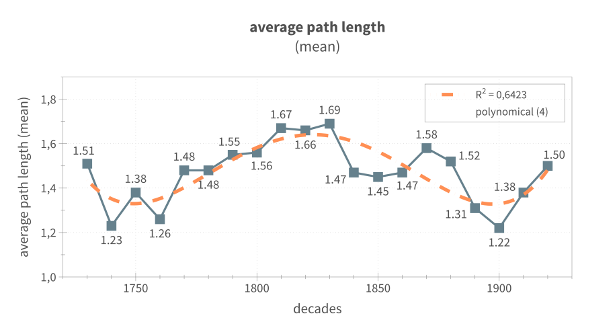

The diachronic extension of our corpus over 200 years of German literary history allows the observation of larger developments in the structural composition of dramatic texts (we outlined some reflections on this in a blog post: https://dlina.github.io/200-Years-of-Literary-Network-Data/). Values referring to networks as a whole will be broached (incl. network size, density, average degree; as an example, we put average-path-length values by decades in Fig. 1), as will be character-related values for each character of each play (centrality measures, primarily) providing information on the distribution of the personae dramatis or their division into 'central' and 'less central' characters. These values will lay the groundwork for the discussion of some global hypotheses of literary history. We will discuss, firstly, the extent to which we can observe a differentiation of the structural composition of drama at the end of the 18th century on the basis of network analysis values: Such a differentiation is to be expected given the coexistence of 'closed' drama (following the doctrines of French classicism) and 'open' drama (mostly influenced by Shakespeare). Secondly, we will discuss some common literary periodising hypotheses (originating from structuralism, social history, or other directions). We will have a closer look at correlations between our network data and well-established traditional periodisations.

4. Evaluation, Part II: Types of Drama

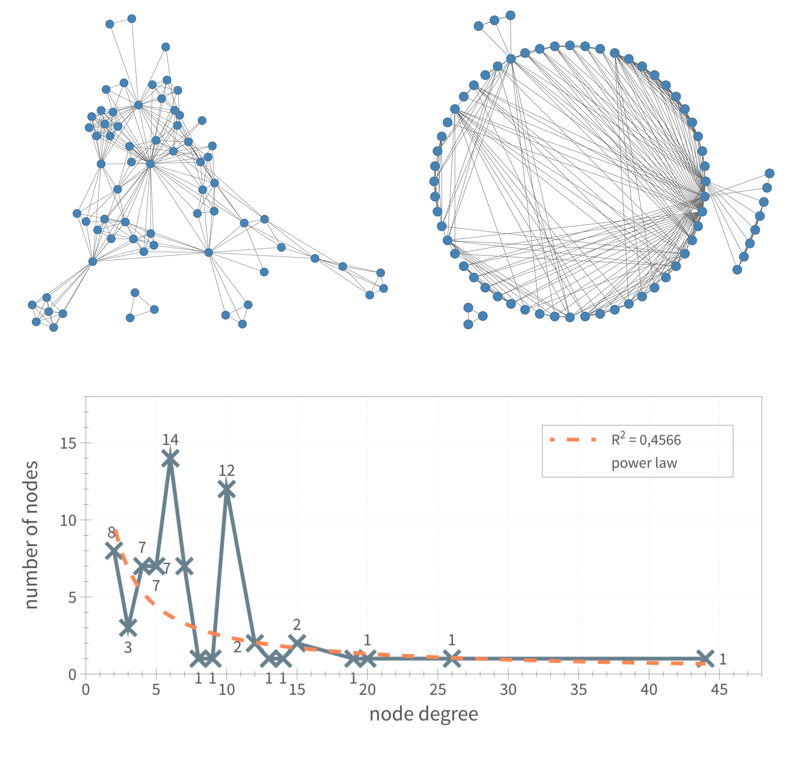

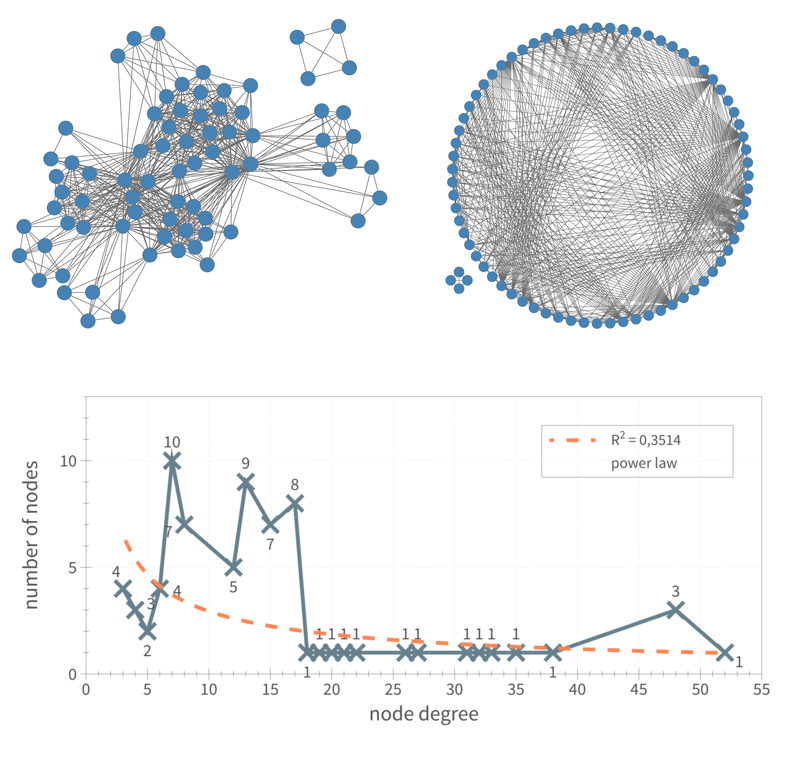

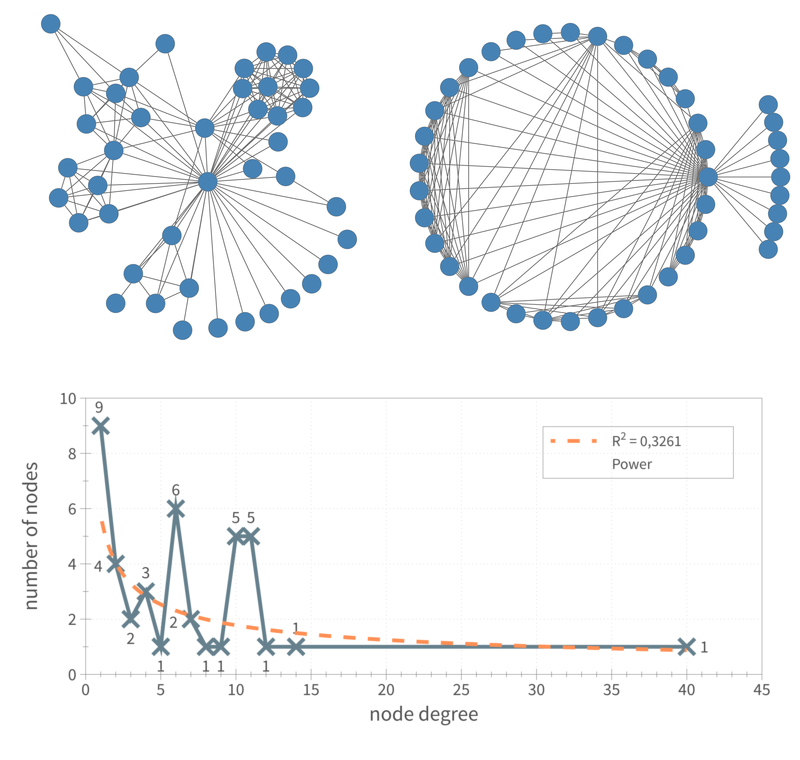

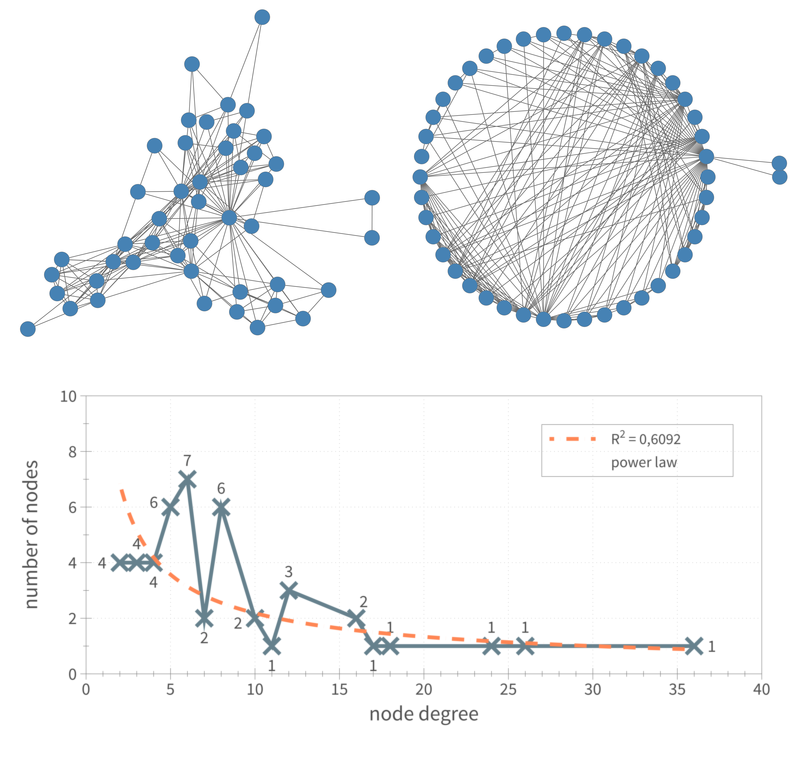

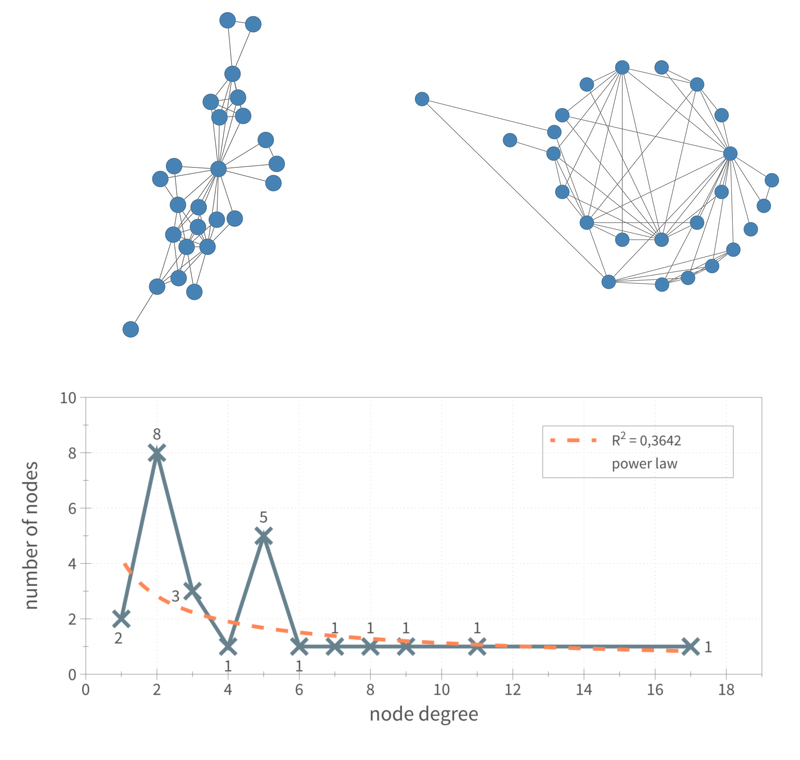

The data raised so far shows how very differently theatre plays were structured in the focal period. Traditional literary studies have developed various typologies for such different types, the most popular in German studies being Volker Klotz's subdivision into 'open' and 'closed' drama. We want to build on this kind of typological impulse and propose a method as to how certain types of structural composition can be distinguished by means of network analysis (and also placed in their historic context). With this proposal we want to take up reflections from research on so-called small-world networks. This branch of research assumes that the values of empirically collected networks often differ significantly from those of corresponding random networks (e.g., graphs generated with the Erdős–Rényi model). Following the approach of Stiller, Nettle and Dunbar 2003, but relying on a much larger set of texts, we investigate the plays in our corpus with regard to their small-world properties (clustering coefficient, average path length, node degree distribution). The results show that there are just a few plays that meet all the criteria (a total of five plays, i.e., just about one percent of the corpus) – see figs. 2.1 to 2.5.

These findings will give us a deeper understanding of different types of structural composition. We shall first direct our attention to forms of networks that – unlike dramas with small-world properties – occur much more frequently in our corpus. Eventually, we will discuss structural characteristics of drama networks exhibiting properties exactly opposite to the properties of small-world dramas (e.g., reverse power-law form in the node degree distribution). It will also be discussed in this context whether we can contrast the strong hierarchical type of small-world drama with an anti-hierarchical type.

- Réka, A. and Barabási, A.-L. (2002). Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Reviews of Modern Physics 74: 47–97.

- Agarwal, A. et al. (2012). Social Network Analysis of Alice in Wonderland. Proceedings of the Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature, Montréal: 88–96.

- de Nooy, Wouter (2006). Stories, Scripts, Roles, and Networks. Structure and Dynamics 1(2) http://escholarship.org/uc/item/8508h946#page-1 (accessed 4 March 2016)

- Elson, D. K., Dames, N. and McKeown, K. R. (2010). Extracting Social Networks from Literary Fiction. Proceedings of the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Uppsala, pp. 138–47.

- Fischer, F., Kampkaspar, D.; Göbel, M. and Trilcke, P. (2015). Digital Network Analysis of Dramatic Texts. DH2015, script: https://dlina.github.io/Our-Talk-at-DH2015/, slides: https://dlina.github.io/presentations/2015-sydney/sydney.html (accessed 4 March 2016).

- Klotz, Volker (1960). Geschlossene und offene Form im Drama. München.

- Lotman, Jurij M. (1972). Die Struktur literarischer Texte. München.

- Marcus, Solomon (1973). Mathematische Poetik. Frankfurt/M.

- Moretti, Franco: Network Theory, Plot Analysis. Stanford Literary Lab Pamphlets, No. 2, 1 May 2011, http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet2.pdf (accessed 4 March 2016).

- Park, G.-M., Sung-Hwan, K. and Cho, H.-G. (2013). Structural Analysis on Social Network Constructed from Characters in Literature Texts. Journal of Computers 8(9): 2442–47, http://ojs.academypublisher.com/index.php/jcp/article/view/jcp080924422447/7672 (accessed 4 March 2016).

- Rydberg-Cox, J. (2011). Social Networks and the Language of Greek Tragedy. Journal of the Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities and Computer Science, 1(3), https://letterpress.uchicago.edu/index.php/jdhcs/article/view/86/91

- Stiller, J., Nettle, D. and Dunbar, Robin I. M. (2003). The Small World of Shakespeare's Plays. Human Nature 14: 397–408.

- Stiller, J. and Hudson, M. (2005). Weak Links and Scene Cliques Within the Small World of Shakespeare. Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology 3: 57–73.

- Titzmann, M. (1977). Strukturale Textanalyse. Theorie und Praxis der Interpretation. München.

- Trilcke, P. (2013). Social Network Analysis (SNA) als Methode einer textempirischen Literaturwissenschaft. Ajouri, Philip; Mellmann, Katja and Rauen, Christoph (eds.): Empirie in der Literaturwissenschaft. Münster, pp. 201–47.