Authors: Francesca Frontini, Carmen Brando, Jean-Gabriel Ganascia

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: literary criticism, entity linking, TEI, visualization

REDEN ONLINE: Disambiguation, Linking and Visualisation of References in TEI Digital Editions

1. Introduction

As Susan Schreibman (2014) points out, a digital edition, as opposed to a printed one, is never really complete as several layers of annotation may always be added to represent and enrich the original content. TEI (Burnard, 2014) allows for several types of information - textual, linguistic and semantic - to be layered and made explicit and retrievable by a machine. Such is the case for instance with what is commonly known as semantic tagging.

In this paper, we focus on Named Entities (NE), in particular names of Persons and Geographical Places. Adding NE mentions is supported by TEI with appropriate tags (such as <persName> and <placeName>), whose addition in a digital critical edition has somewhat the same function that indexes of places and persons have in a printed one. As mentions may be ambiguous (same string for different people, same place with different names,....) some referencing and disambiguating identifiers are required. But digital editions allow for much more than simple internal referencing. By pointing to external sources, structured information contained in the form of linked data in the semantic web becomes available to scholarly research.

In this work we present REDEN ONLINE, a system that enables scholars to automatically add external references to annotations of persons and places. The system is a web interface taking TEI as input, where mentions are already marked up, and automatically disambiguates and links such entities to an appropriate linked data set using a graph based algorithm for disambiguation. Moreover, our system provides data aggregation and visualization facilities by using the information found in the reference sources.

2. Previous work and general context

Semantic tagging is a hot topic in the digital humanities. Tools for semantic enrichment are, such as Pundit (Grassi et al., 2012, 2013), already available and allow for the interactive and intuitive annotation of portions of text. Automatic Named Entity Recognition and Linking techniques may be implemented to detect mentions and to suggest links to external knowledge bases.

Input formats to such systems may vary from plain text to html, but ideally a tool should process available standard formats, such as TEI-XML for text and RDF/OWL for information. Using linked data sources for disambiguation and enrichment is thus strongly recommended. By doing this, external sources of structured and regularly updated information can be made available to the scholar without having to be directly incorporated into the inline annotation, that can be left as simple as possible. This in turn allows for several customizable views, as linked data sources may be queried with the SPARQL query language to retrieve only the amount of external information that is necessary for a given task.

The treatment of spatial and temporal information is a typical task for which this approach is particularly effective; the availability of geographical databases and the complexity of the information are best accessed by pointing from within the digital edition to an external link. But also other types of semantic information seem to be particularly apt for connection to rich linked databases. So for instance bibliometric sources can be used to enrich texts with additional information on authors.

Typical targets for references are DBpedia and Geonames, that, for their genericity and connection to other sources, are at the heart of the linked data cloud. But they may be supplemented by more domain specific sources of information. For instance, Pleiades provides geo-historical information for ancient places.

3. Our project

REDEN ONLINE is set against the background of work carried out at LABEX OBVIL in Paris, where quality digital editions for French literary texts and criticism are produced and used in research and higher education. Recently a series of projects were carried out to semi-automatically annotate and reference places, organizations and authors. Gold standards were also produced, in close contact with researchers in French literature, so as to establish guidelines of annotation that best suit their ongoing research.

The general purpose is to provide tools for both:

- augmented close reading, to enable researchers to access more information on a specific text portion

- distant reading and data aggregation, so as to be able to detect trends in large portions of texts (Moretti, 2007)

OBVIL literary scholars are interested in plotting the distribution of the mentions of given authors over time in French literary criticism, in order to study the appreciation of Molière over the centuries, or in producing charts representing the distributions of professions in authors mentioned in given periods, to trace the influence of scientists and their ideas on art and literature in the age of positivism (Riguet, 2015). Other visualizations captured the emerging influence of foreign countries in the French literary panorama over time by combining the date of the publication of the essays with the detected toponyms.

NLP technologies are used to facilitate various aspects of the semantic enrichment of TEI editions, in an annotation echosystem where texts are first processed and then manually checked. The detection of mentions of places, authors (and also organizations) was tackled by using a Named Entity Recognizer and Classifier (UNERD, Mosallam et al., 2014).

Once the entities are correctly detected and classified, external references need to be added to disambiguate mentions and to connect them to additional information. To this purpose we developed REDEN 1, a Named Entity Linker that uses a graph-based algorithm and linked data sets to identify the correct referent for each mention (Brando et al., 2015, Frontini et al., 2015a, Frontini et al., 2015b for the technical details).

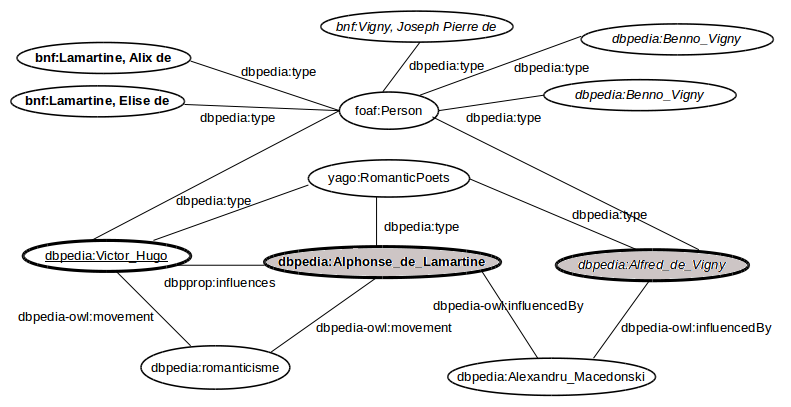

REDEN's input consists of a TEI text with detected mentions and several parameters specifying among others the class of entities to be detected, the reference base to use and a set of pre-compiled indexes. REDEN is applied for each class of entities separately, and works at best when several mentions are disambiguated at the same time. It retrieves all candidate referents for each mention of a context (say a paragraph) and then all the available information from the semantic web. It builds a sub-graph of all candidates and chooses the correct referents for each mention with the help of the formal relations between them. From Figure 1 you can get an intuition of how REDEN works.

So far our efforts have concentrated on the production of a text annotation and referencing pipeline for the production of such enriched TEIs with annotated and referenced mentions. Their exploitation for data aggregation and visualization was carried out offline and with ad hoc processing tools. With REDEN ONLINE we now want to make linking technology available online while at the same time providing users with some generic visualization of the results.

In what follows, we present the REDEN ONLINE interface with some screenshots from an example where two texts of the Labex OBVIL 2 digital library have been automatically linked to external sources, namely:

- L’Hérésiarque et cie, a collection of short stories by Guillaume Apollinaire, published in 1910 - place mentions linked to DBpedia entries.

- Réflexions sur la littérature a series of essays on French literary criticism by Albert Thibaudet, published in 1936 - author's mentions linked to entries in the linked data base of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF).

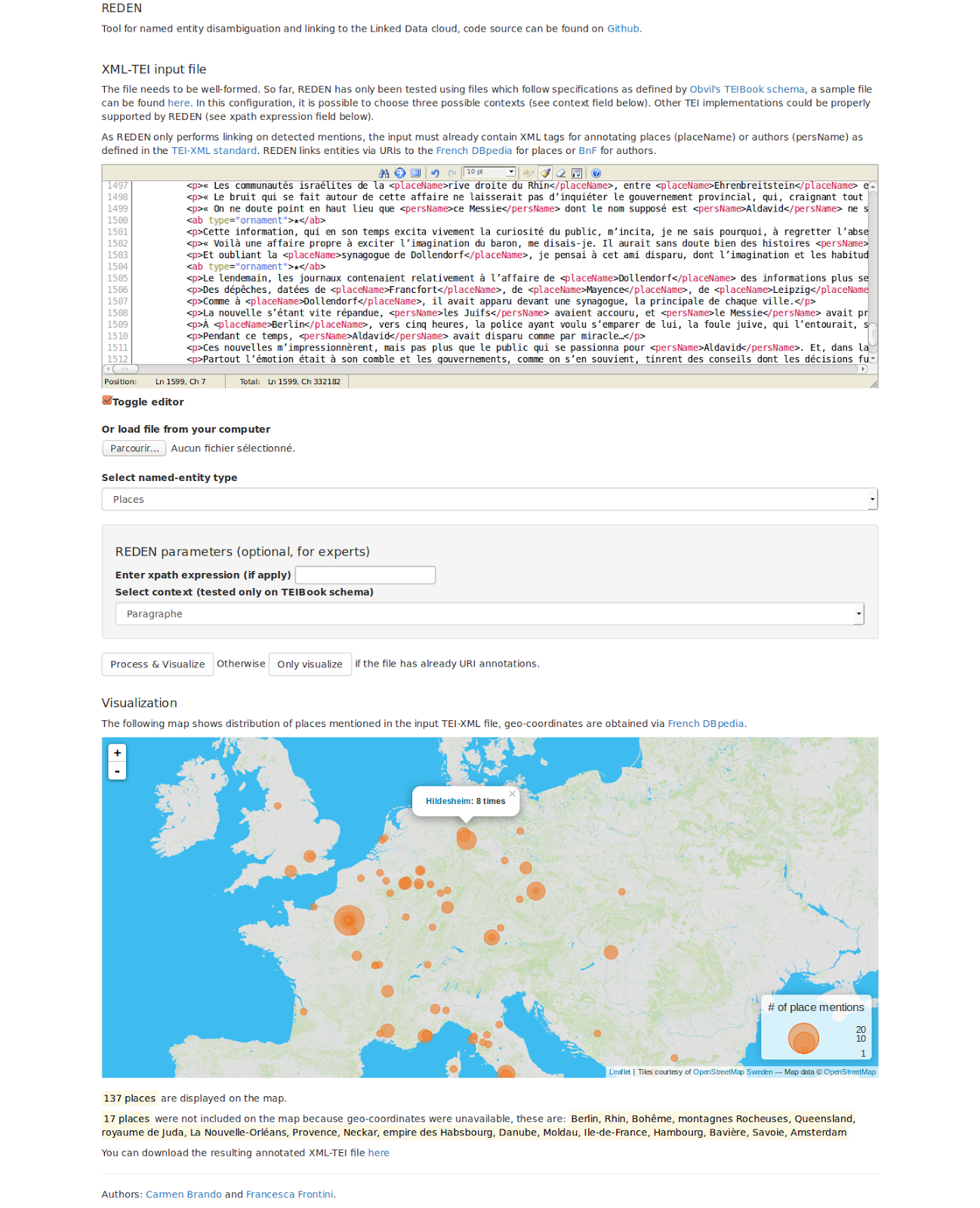

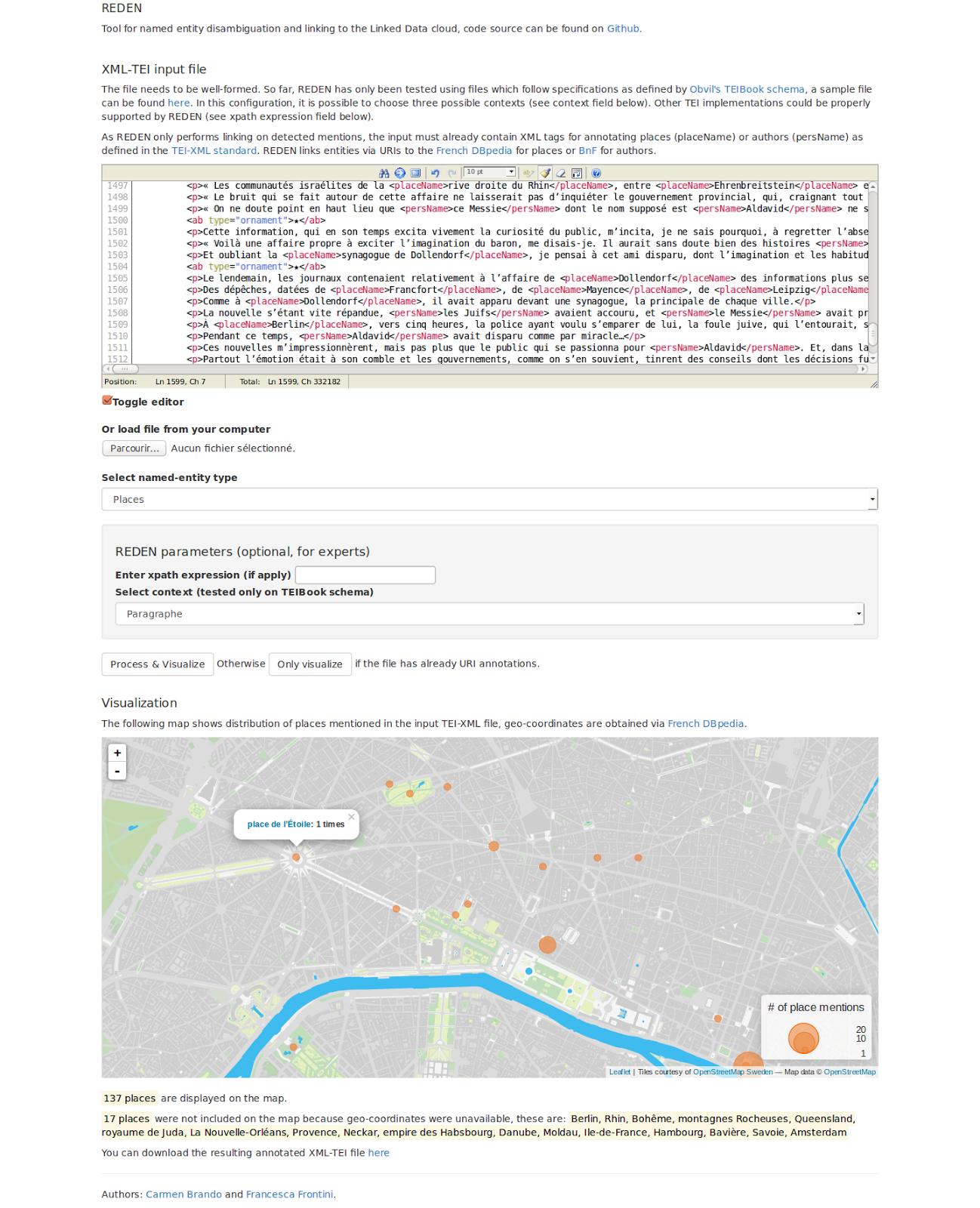

The user (Figure 2) loads a TEI text with annotated <placeName> or <personName> tags, chooses which class of entities to process (places or nouns) and the system runs the disambiguation and linking algorithm against the given linked data base - here French DBpedia and/or BnF. Then external information is extracted from the source and used for generating a particular view of the text. The result is a summing up of the disambiguated locations (some place names may be non resolvable because they are absent from the linked data base) and a visualization.

For locations the visualization consists in an interactive map that also takes frequency of mention into account. Coordinates are retrieved from DBpedia when available and the map can be zoomed in, up to the level of streets (see Figure 3 where some places in Paris have been identified in the text by Apollinaire), when relevant.

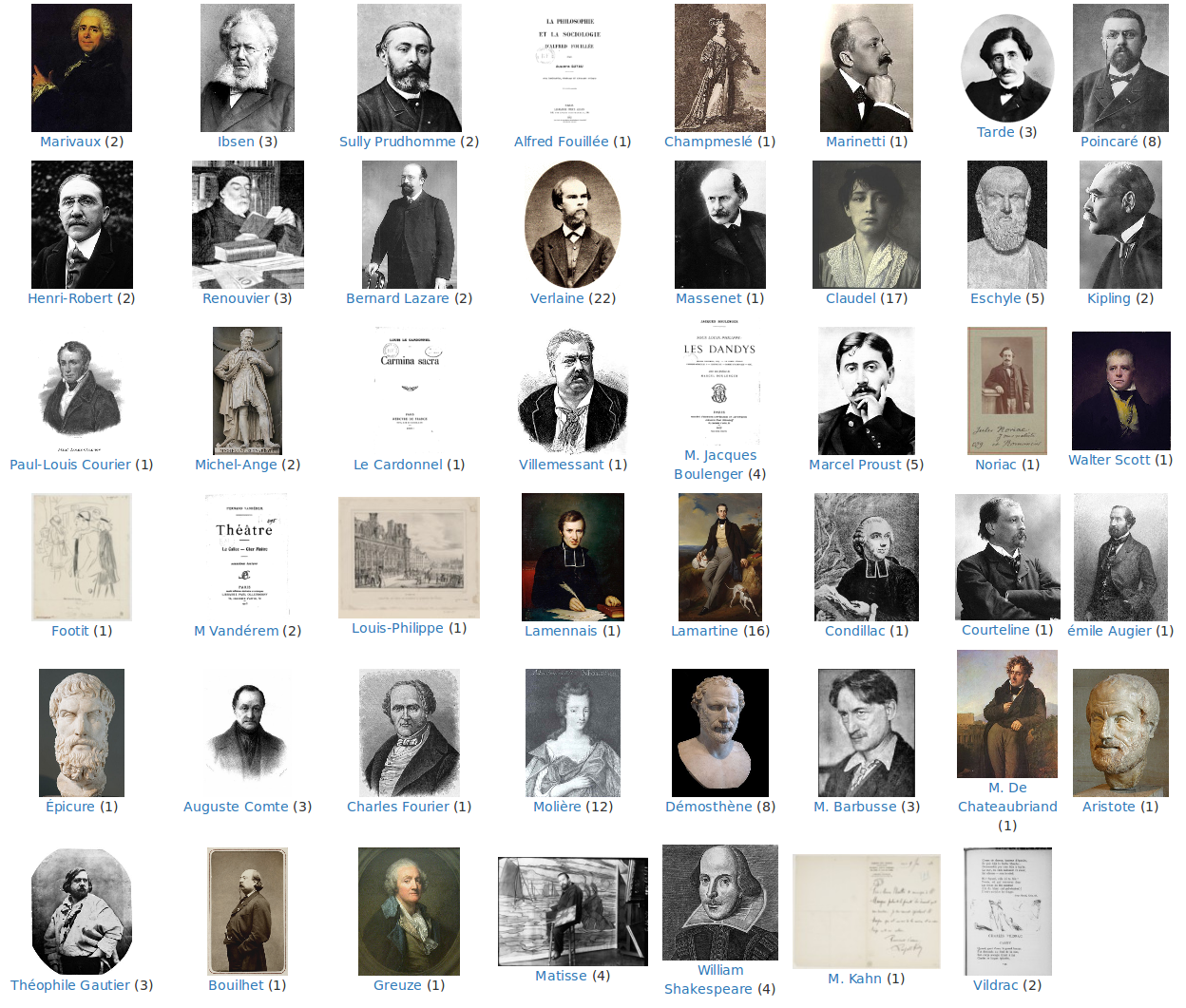

For persons (see Figure 4), portraits of authors are automatically downloaded and visualized.

4. Conclusion

The conference presentation will demonstrate REDEN ONLINE, a web based tool that enables researchers to connect place names and person names in their texts to existing linked data sources. The underlying technology will also be explained, in particular its use of standard formats, such as TEI and RDF for the linking algorithm, and GeoJSON for the creation of the map. We will also argue in favour of our economicity approach, namely the choice of not embedding semantic information in the TEI, which enables the use of different databases and the production of ad hoc "views" of the document.

It is well known that aggregation and visualizations techniques may "assist the critic in the unfolding of interpretive possibilities" (Ramsay, 2008) when analysing texts. This tool has been particularly designed for the study of literature and literary criticism; in the presentation examples of use will be given using ongoing research on Apollinaire, highlighting how the visual representation of the itineraries contained in the stories may be considered as a form of novel "digital reading" of the text.

- Brando, C., Frontini, F. and Ganascia, J. G. (2015). Disambiguation of Named Entities in Cultural Heritage Texts Using Linked Data Sets. In Morzy, T., Valduriez, P. and Bellatreche, L. (Eds.), New Trends in Databases and Information Systems. (Communications in Computer and Information Science 539). Springer International Publishing, pp. 505–14.

- Burnard, L. (2014). What Is the Text Encoding Initiative? How to Add Intelligent Markup to Digital Resources. (Encyclopédie Numérique). Marseille: OpenEdition Press.

- Elliott, T. and Gillies, S. (2009). Digital geography and classics. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 3(1).

- Frontini, F., Brando, C. and Ganascia, J. G. (2015a). Domain-adapted named-entity linker using Linked Data. Proceedings of the Workshop on NLP Applications: Completing the Puzzle, vol.1386, Aachen: M. Jeusfeld c/o Redaktion Sun SITE, Informatik V, RWTH Aachen. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1386/named_entity.pdf. (accessed 27 October 2015).

- Frontini, F., Brando, C. and Ganascia, J. G. (2015b). Semantic Web based Named Entity Linking for Digital Humanities and Heritage Texts. SW4SH 2015 Semantic Web for Scientific Heritage 2015, vol. 1364, Aachen: M. Jeusfeld c/o Redaktion Sun SITE, Informatik V, RWTH Aachen, pp. 77–88, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1364/paper9.pdf.

- Grassi, M., et al. (2012). Pundit: Semantically Structured Annotations for Web Contents and Digital Libraries. Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Semantic Digital Archives, Paphos, Cyprus, pp. 49–60.

- Grassi, M., et al. (2013). Pundit: Augmenting Web Contents with Semantics. Literary and Linguisting Computing, 28(4): 640–59.

- Grossner, K., Janowicz, K. and Keßler, C. (2016). Place, Period, and Setting for Linked Data Gazetteers. In Mostern, Ruth, Berman, Lex and Southall, H. (Eds.), Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers. Bloomington, Indiana University Press http://geog.ucsb.edu/~jano/GrossnerJanowiczKessler_submitted_draft.pdf (accessed 27 October 2015).

- Janowicz, K. (2009). The Role of Place for the Spatial Referencing of Heritage Data. The Cultural Heritage of Historic European Cities and Public Participatory GIS Workshop. The University of York, UK.

- Jones, C. B., et al. (2008). Modelling vague places with knowledge from the Web. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 22(10): 1045–65. doi:10.1080/13658810701850547.

- Montuschi, P. and Benso, A. (2014). Augmented Reading: The Present and Future of Electronic Scientific Publications. Computer, 47(1): 64–74 doi:10.1109/MC.2013.256.

- Morbidoni, C., et al. (2013). Semantic Augmentation and Externalization in the Humanities: a Demonstrative Use Case. Proceedings of the Digital Humanities 2013, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Moretti, F. (2007). Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History. London: Verso Books.

- Mosallam, Y., Abi-Haidar, A. and Ganascia, J. G. (2014). Unsupervised Named Entity Recognition and Disambiguation: An Application to Old French Journals. Advances in Data Mining. Applications and Theoretical Aspects. Springer, pp. 12–23. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-08976-8_2 (accessed 27 July 2015).

- Murrieta-Flores, P. and Gregory, I. (2015). Further Frontiers in GIS: Extending Spatial Analysis to Textual Sources in Archaeology. Open Archaeology, 1(1). doi:10.1515/opar-2015-0010. http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/opar.2014.1.issue-1/opar-2015-0010/opar-2015-0010.xml (accessed 27 October 2015).

- Ramsay, S. (2008). Algorithmic Criticism. Companion to Digital Literary Studies. (Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Professional http://www.digitalhumanities.org/companionDLS/ (accessed 24 February 2010).

- Riguet, M. (in press). L’impact de la physiologie dans la critique littéraire de la fin du XIXe siècle : l’exemple de Claude Bernard, actes du colloque Littérature et Science au xixe siècle, dirigée par Elsa Courant et Romain Enriquez, ENS Ulm, avril 2015, Épistémocritique.

- Schreibman, S. Digital Scholarly Editing. In Price, K. M. and Siemens, R. (eds), Literary Studies in the Digital Age. Modern Language Association of America http://dlsanthology.commons.mla.org/digital-scholarly-editing/ (accessed 5 March 2014).

- Nadeau, D. and Sekine, S. (2007). A survey of named entity recognition and classification. Lingvisticae Investigationes, 30(1): 3–26 doi:10.1075/li.30.1.03nad.

- Stadler, C., et al. (2012). LinkedGeoData: A Core for a Web of Spatial Open Data. Semantic Web Journal, 3(4): 333–54.

- Hooland, S., et al. (2013). Exploring entity recognition and disambiguation for cultural heritage collections. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities doi:10.1093/llc/fqt067. http://dsh.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/12/02/llc.fqt067.

REDEN is open source; you can find the code at https://github.com/cvbrandoe/REDEN.

Find more information on OBVIL and ist digital library at http://obvil.paris-sorbonne.fr/.