Authors: Rui Hu, Jean-Marc Odobez, Daniel Gatica-Perez

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: Shape descriptor, image retrieval, Maya hieroglyph

Assessing a Shape Descriptor for Analysis of Mesoamerican Hieroglyphics: A View Towards Practice in Digital Humanities

1. Introduction

Technological advances in digitization, automatic image analysis and information management are enabling the possibility to analyze, organize and visualize large cultural datasets. As one of the key visual cues, shape feature has been used in various image analysis tasks such as handwritten character recognition (Fischer, 2012; Franken, 2013), sketch analysis (Eitz, 2012), etc. We assess a shape descriptor, within the application domain of Maya hieroglyphic analysis. Our aim is to introduce this descriptor to the wider Digital Humanities (DH) community, as a shape analysis tool for DH-related applications.

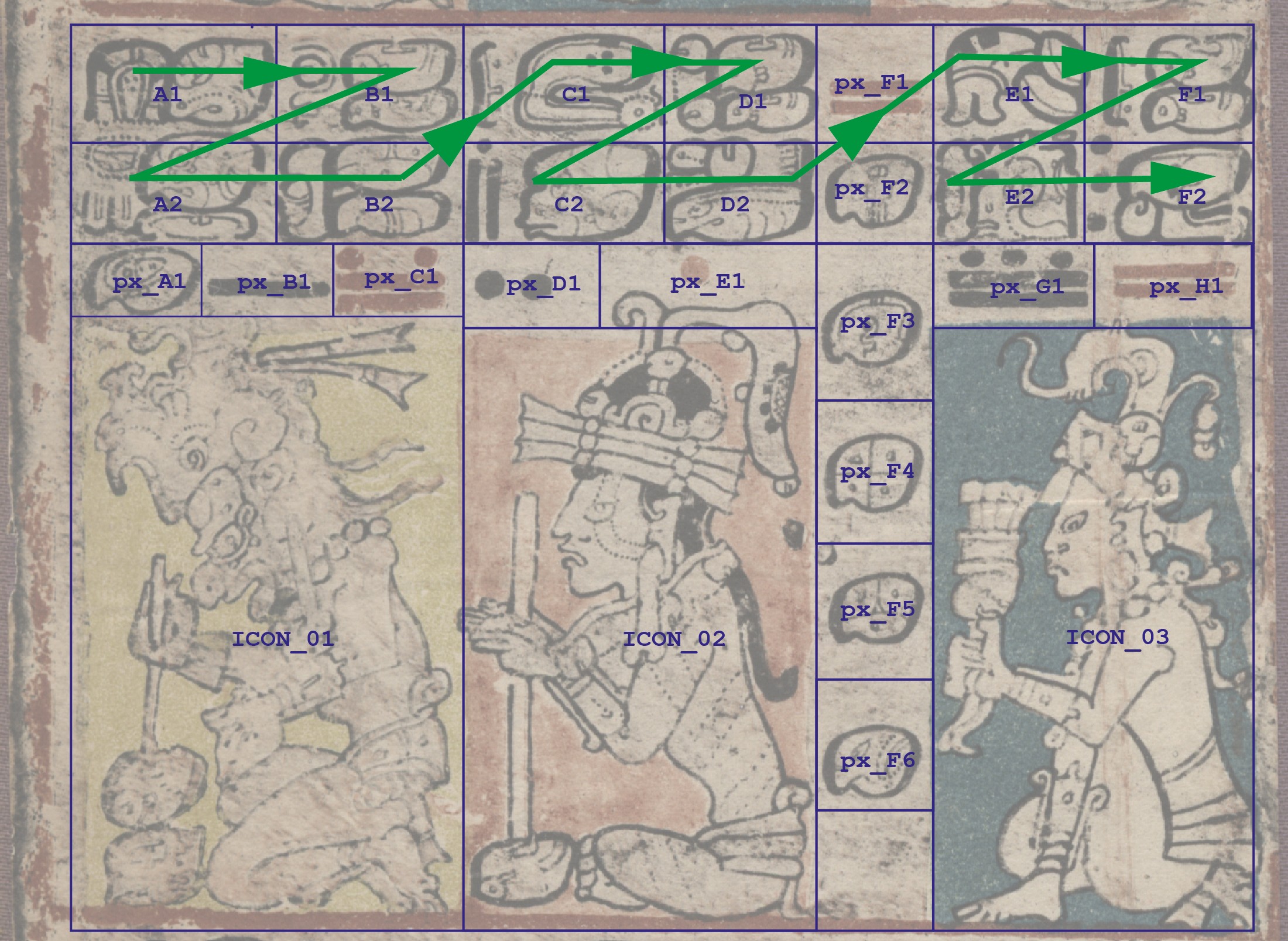

The Maya civilization is one of the major cultural developments in ancient Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya language infused art with uniquely pictorial forms of hieroglyphic writing, which represents an exceptionally rich legacy (Stone, 2011). Most Maya texts were written during the Classic period (AD 250-900) of the Maya civilization on various media types, including stone monuments. A special class of Maya texts was written on bark cloths as folding books from the Post-Classic period (AD 1000-1519). Only three such books (namely the Dresden, Madrid and Paris codices) are known to have survived the Spanish Conquest. A typical Maya codex page contains icons, main sign glyph blocks, captions, calendric signs, etc. Fig. 1 illustrates an example page segmented into main elements (Gatica-Perez, 2014). In this paper, we are interested in the main signs.

Maya hieroglyphic analysis requires epigraphers to spend a significant amount of time browsing existing catalogs to identify individual glyphs. Automatic Maya glyph analysis has been addressed as a shape matching problem, and a robust shape descriptor called Histogram of Orientation Shape Context (HOOSC) was developed in (Roman-Rangel, 2011). Since then, HOOSC has been successfully applied for automatic analysis of other cultural heritage data, such as Oracle-Bones Inscriptions of ancient Chinese characters (Roman-Rangel, 2012), and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs (Franken, 2013). It has also been applied for generic sketch and shape image retrieval (Roman-Rangel, 2012). Our recent work extracted statistic Maya language model and incorporated it for glyph retrieval (Hu, 2015).

The goal of this paper is two-fold:

- Introduce the HOOSC descriptor to be used in DH-related shape analysis tasks (code available at: http://www.idiap.ch/paper/maaya/hoosc/);

- Discuss key issues for practitioners, namely the effect that certain parameters have on the performance of the descriptor. We describe the impact of such choices on different data types, specially for 'noisy' data as it is often the case with DH image sources.

2. Automatic Maya Hieroglyph Recognition

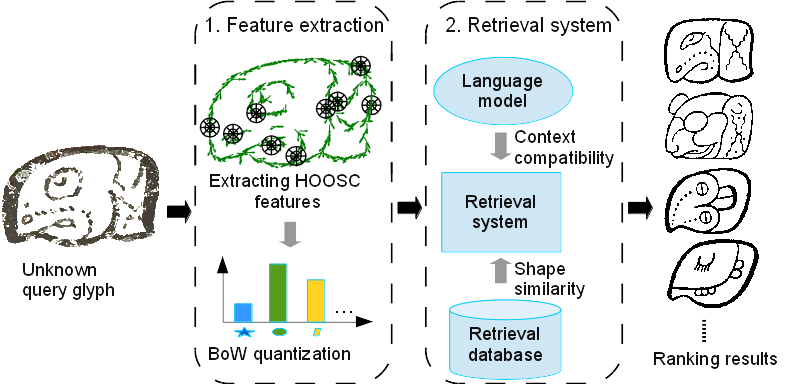

We conduct glyph recognition with a retrieval system proposed in (Hu, 2015). Unknown glyphs are considered as queries to match with a database of known glyphs (retrieval database). Shape and context information are considered. Fig.2 illustrates a schema of our approach. We study the effect of different HOOSC parameter choices on the retrieval results.

2.1. Datasets

We use three datasets, namely the 'Codex', 'Monument' and 'Thompson'. The first two are used as queries to search within the retrieval database ('Thompson').

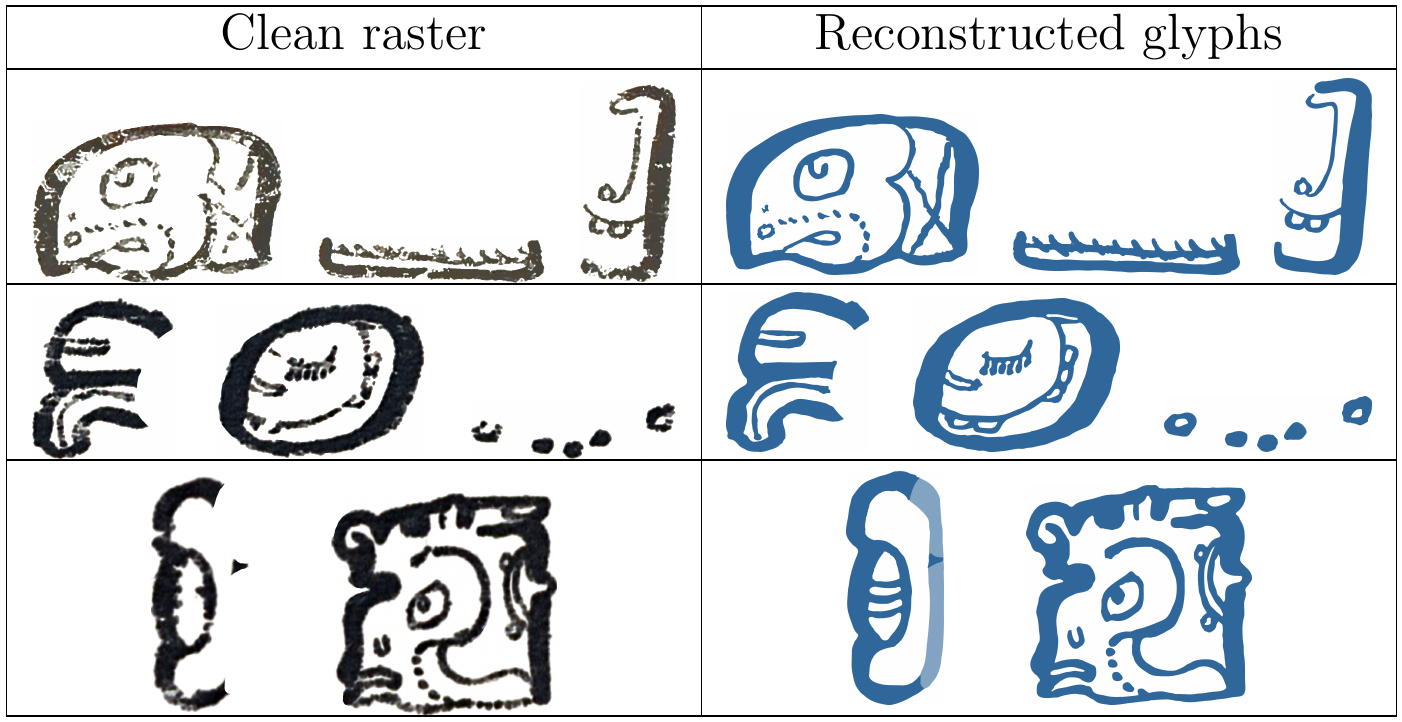

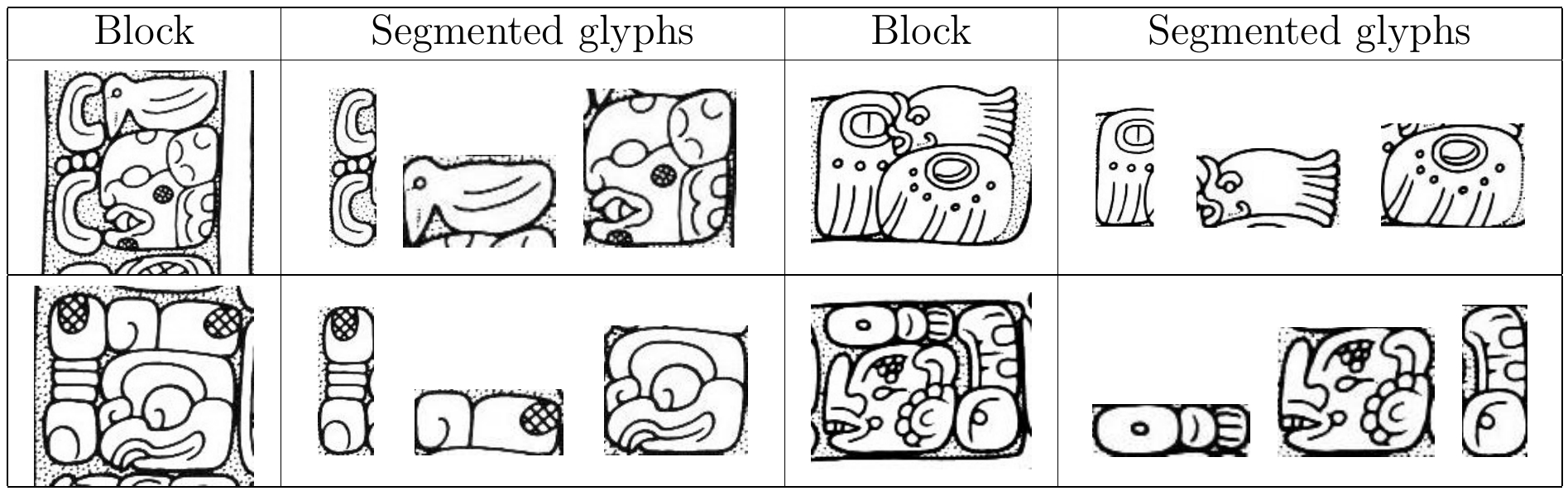

The 'Codex' dataset contains glyph blocks from the three surviving Maya codices. See Fig.3 for examples. Glyph blocks are typically composed of combinations of individual signs. Fig.4 shows individual glyphs segmented from blocks in Fig.3. Note the different degradation levels across samples. We use two sub-datasets: 'codex-small', composed of 156 glyphs segmented from 66 blocks, for which we have both clean raster and high-quality reconstructed vectorial representations (see Fig.4) to study the impact of the different data qualities on the descriptor; and a 'codex-large' dataset, which is more extensive, comprising only the raster representation of 600 glyphs from 229 blocks.

The 'Monument' dataset is an adapted version of the Syllabic Maya dataset used in (Roman-Rangel, 2011), which contains 127 glyphs of 40 blocks extracted from stone monuments. It is a quite different data source to the codex data, in terms of historical period, media type, and data generation process. Samples are shown in Fig.5.

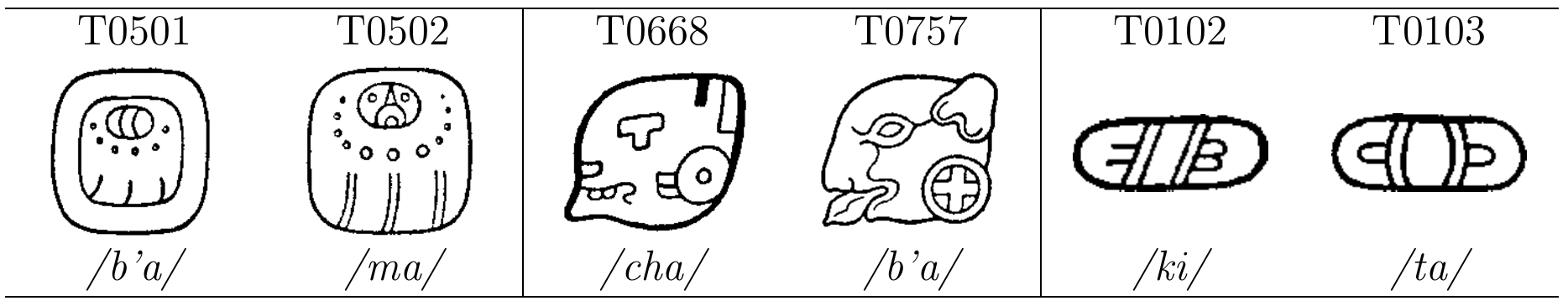

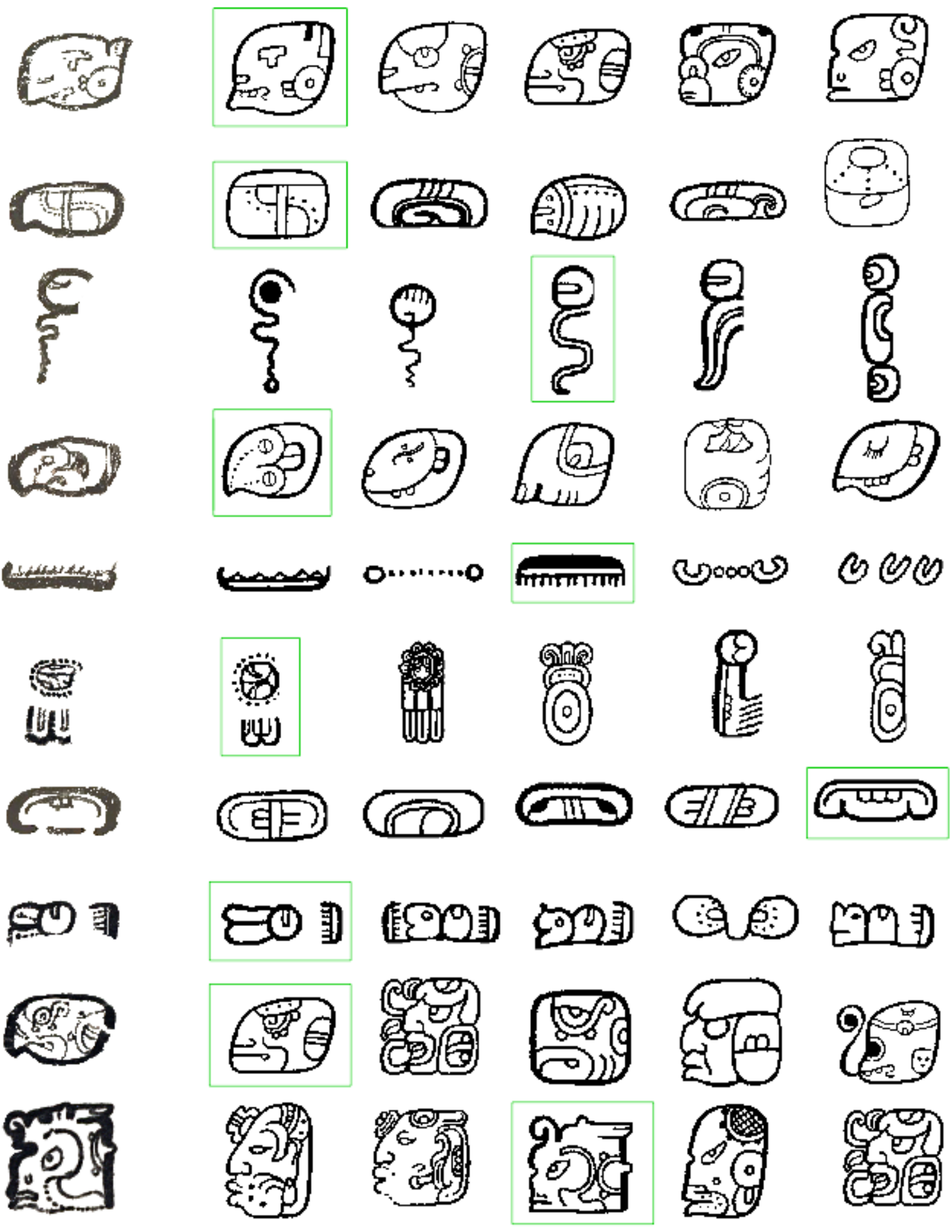

To form the retrieval database ('Thompson'), we scanned and segmented all the glyphs from the Thompson catalog (Thompson, 1962). The database contains 1487 glyph examples of 892 different sign categories. Each category is usually represented by a single example image. Sometimes multiple examples are included; each illustrates a different visual instance or a rotation variant. Fig.6 shows glyph examples.

2.2. Shape-based retrieval

Feature extraction and similarity matching are the two main steps for our shape-based glyph retrieval framework.

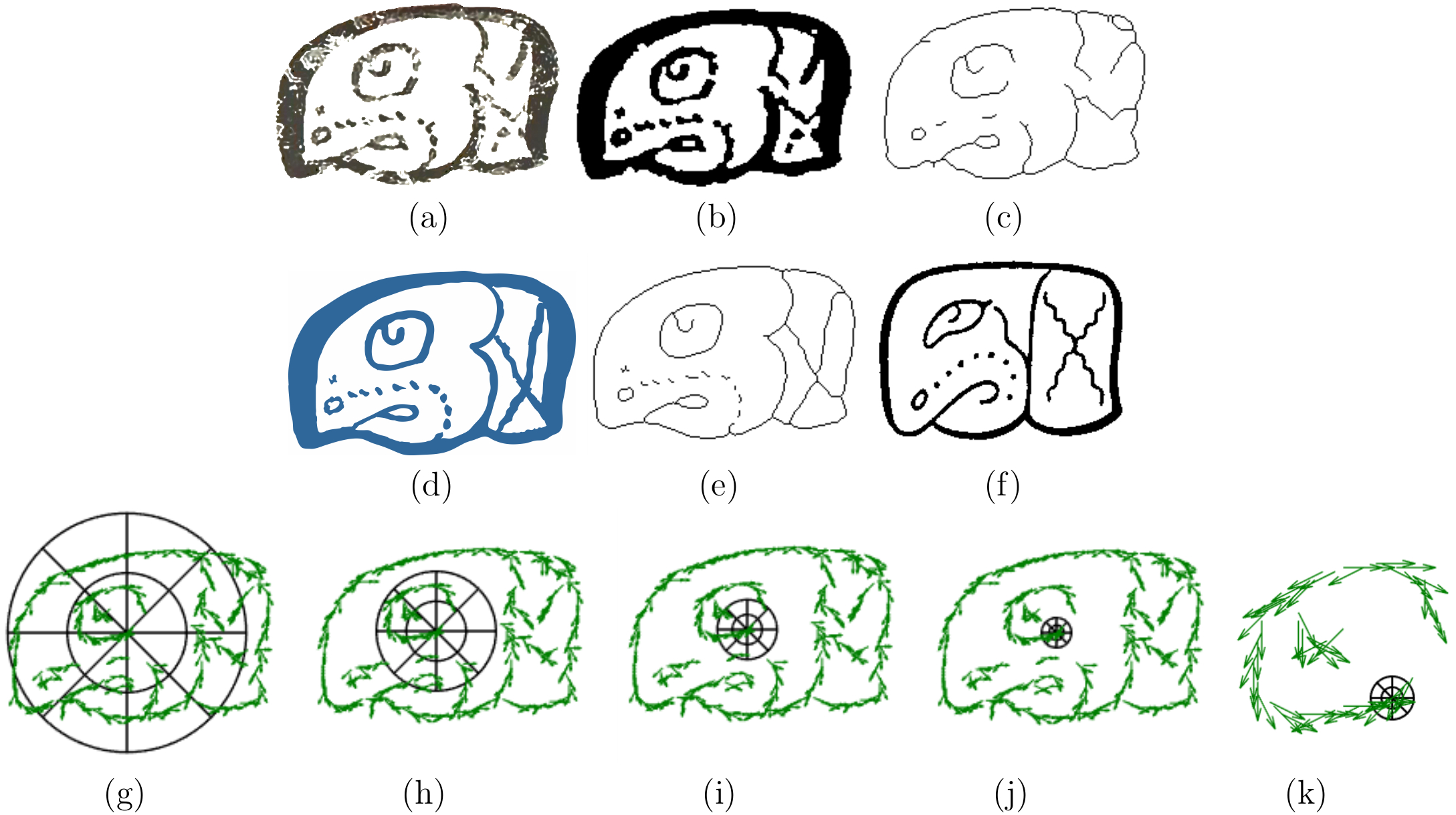

Glyphs are first pre-processed into thin lines. To do so, an input glyph (Fig.7(a)) is first converted into a binary shape (Fig.7 (b)). Thin lines (Fig.7(c)) are then extracted through mathematical morphology operations. Fig.7(c)-(d) show the high-quality reconstructed binary image, and the extracted thin lines.

HOOSC descriptors are then computed at a subset of uniformly sampled pivot points along the thin lines. HOOSC combines the strength of Histogram of Orientation Gradient (Dalal, 2005) with circular split binning from the shape context descriptor (Belongie, 2002). Given a pivot point, the HOOSC is computed on a local circular space centred at the pivot's location, partitioned into rings and evenly distributed angles. Fig.7 (g)-(k) show different sizes of the circular space (referred to as spatial context) partitioned into 2 rings and 8 orientations. A Histogram-of-orientation-gradient is calculated within each region. The HOOSC descriptor for a given pivot is the concatenation of histograms of all partitioned regions.

We then follow the Bag-of-Words (BoW) approach, where descriptors are quantized as visual words based on the vocabulary obtained through K-means clustering on the set of descriptors extracted from the retrieval database. A histogram representing the count of each visual word is then computed as a global descriptor for each glyph. In all experiments, we use vocabulary size k=5000.

Each query is matched with glyphs in the retrieval database, by computing shape feature similarity using the L1 norm distance.

2.3. Incorporating context information

Shape alone is often ambiguous to represent and distinguish between images. In the case of our data, different signs often share similar visual features (see Fig.6); glyphs of the same sign category vary with time, location, and the different artists who produced them (see Fig.8); additionally, surviving historical scripts often lose visual quality over time. Context information can be used to complement the visual features.

Glyph co-occurrence within single blocks encodes valuable context information. To utilize this information, we arrange glyphs within a single block into a linear string according to the reading order (see Fig.4 and Fig.5), and consider the co-occurrence of neighbouring glyphs using an analogy to a statistical language model. For each unknown glyph in the string, we compute its probability to be labelled as a given category by considering not only the shape similarity, but also the compatibility to the rest of the string.

We apply the two language models extracted in (Hu, 2015), namely the ones derived from the Maya Codices Database (Vail, 2013) and the Thompson catalog (Thompson, 1962), which we refer to as the 'Vail' and the 'Thompson' models. We use Vail model with smoothing factor α=0 for the 'Codex' data, and the Thompson model with α=0.2 for the 'Monument' data.

3. Experiments and Results

Our aim is to demonstrate the effect of various HOOSC parameters on retrieval results.

3.1. Experimental setting

We illustrate the effect of 3 key parameters:

- Size of the spatial context region within which HOOSC is computed

A larger region encodes more context information and therefore captures more global structure of the shape. However, in the case of image degradation, a larger region could contain more noise. We evaluate five different spatial contexts as shown in Fig.7(g)-(k). The circular space is distributed over 8 angular intervals.

- Number of rings to partition the local circular region

This parameter represents different partition details. We evaluate either 1 or 2 rings, the inner ring covers half the distance to the outer ring. Each region is further characterized by a 8-bin histogram of the local orientations.

- Position information

Relative position (i, j) of a pivot in the 2-D image plane can be concatenated to the corresponding HOOSC feature.

3.2. Results and discussion

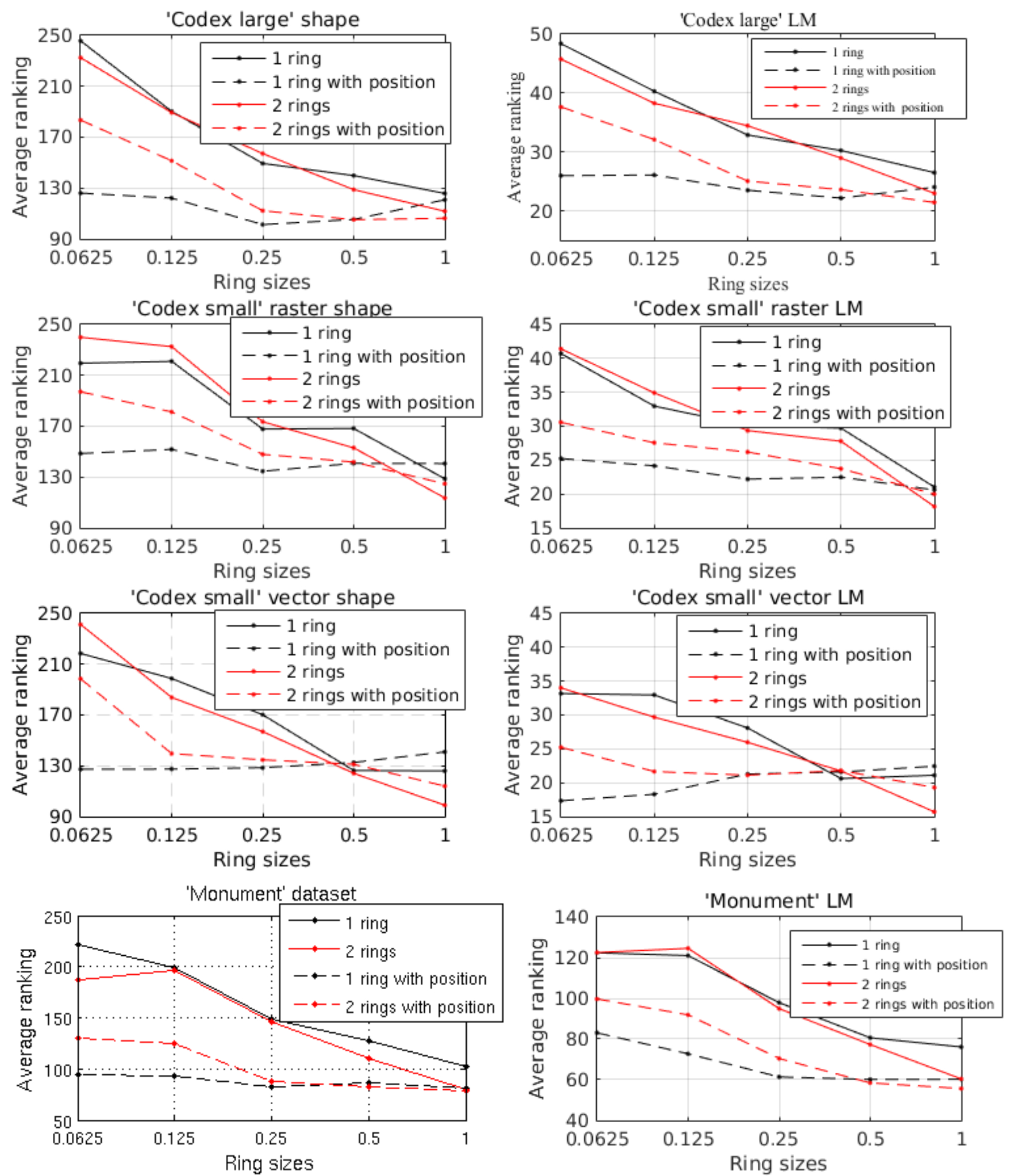

Fig.9 shows the average groundtruth ranking in the retrieval results with different parameter settings, on three query sets, e.g. 'Codex-large', 'Codex-small' and 'Monument'. Each query image usually has only one correct match (groundtruth) in the retrieval database. The smaller the average ranking value, the better the result. From Fig.9 we can see the following:

- In most cases, the best results are achieved by using the largest spatial context, with finer partitioning details (2 rings in our case);

- When the location information is not considered, results show a general trend of improving with increasing ring sizes. However, the results are more stable when the position information is encoded, e.g. a smaller ring size can also achieve promising results when the location information is incorporated. This is particularly useful when dealing with noisy data, where a smaller ring size is preferred to avoid extra noise been introduced by a larger spatial context;

- The results do not benefit from a finer partition, when a small spatial context is considered. However, results improve with finer partitions, when the spatial context becomes larger.

- Position information is more helpful when a small spatial context is considered.

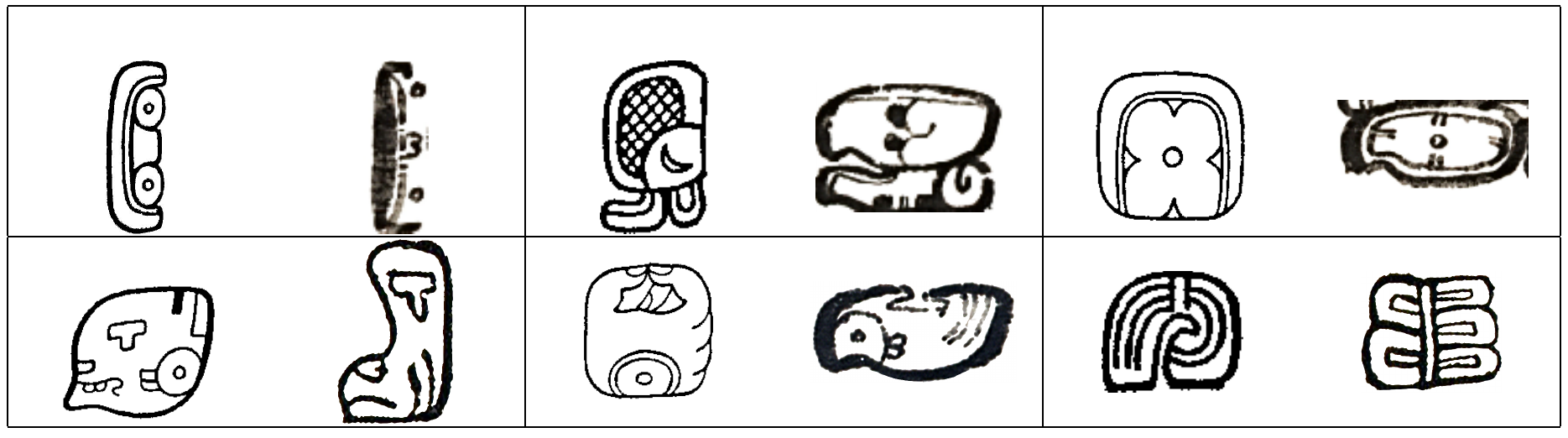

Fig.10 shows example query glyphs and their top returned results.

4. Conclusion

We have introduced the HOOSC descriptor to be used in DH-related shape analysis tasks. We discuss the effect of parameters on the performance of the descriptor. Experimental results on ancient Maya hieroglyph data from two different sources (codex and monument) suggest that a larger spatial context with finer partitioning detail usually leads to better results, while a smaller spatial context with location information is a good choice for noisy/damaged data. The code for HOOSC is available so DH researchers can test the descriptor for their own tasks.

5. Acknowledgement

We thank Edgar Roman-Rangel for co-inventing the HOOSC algorithm and providing the original code. We also thank Carlos Pallán Gayol, Guido Krempel, and Jakub Spotak for producing the data used in this paper. Finally, we thank the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) for their support, through the MAAYA project.

Figure 10. Example queries (first column) and their top returned retrieval results, ranked from left to right in each row. Groundtruth images are highlighted in green bounding boxes.

- Belongie, S., Malik, J., and Puzicha, J. (2002). Shape Matching and Object Recognition using Shape Contexts. PAMI. pp. 509-22.

- Dalal, N., and Triggs, B. (2005). Histogram of Oriented Gradients for Human Detection. In CVPR. pp. 886-93.

- Eitz, M., et al. (2012). Sketch-based shape retrieval. ACM Transactions on Graphics. 31: 1-10.

- Fischer, A., et al. (2012). The HisDoc Project. Automatic Analysis, Recognition, and Retrieval of Handwritten Historical Documents for Digital Libraries. InterNational and InterDisciplinary Aspects of Scholarly Editing.

- Franken, M., and Gemert, J. C. (2013). Automatic Egyptian Hieroglyph Recognition by Retrieving Images as Texts. ACM MM, pp. 765-68.

- Gatica-Perez, D., et al. (2014). The MAAYA Project: Multimedia Analysis and Access for Documentation and Decipherment of Maya Epigraphy. Digital Humanities Conference.

- Hu, R., et al. (2015). Multimedia Analysis and Access of Ancient Maya Epigraphy: Tools to support scholars on Maya hieroglyphics. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, pp. 75-84.

- Roman-Rangel, E. (2012). Statistical Shape Descriptors for Ancient Maya Hieroglyphs Analysis. PhD thesis, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne.

- Roman-Rangel, E., et al. (2011). Analyzing Ancient Maya Glyph Collections with Contextual Shape Descriptors. IJCV, pp. 101-17.

- Stone, A.J. and Zender, M. (2011). Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. Thames and Hudson Limited Publisher.

- Thompson, J. E. S. (1962). A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Vail, G., and Hernández, C. (2013). The Maya Codices Database, Version 4.1. A website and database available at http://www.mayacodices.org/.