Authors: Marissa Lynn Gemma, Ryan James Heuser

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: dialogue, lexical bundles, fiction, nineteenth-century, narration

Building Blocks of Fiction: Lexical Bundles in Nineteenth-Century Novels

1. Introduction

Several decades ago, corpus linguists undertook systematic analyses of a lexical unit larger than the individual word but smaller than syntactical or phrasal units—multi-word sequences they called “lexical bundles” (Biber et al., 1999: 989; Biber and Conrad 1999: 58). Lexical bundles are extremely common collocations of three or more words, such as “I want to”, “it was a”, or “going to be a.” Unlike idioms or clichés, which are statistically very rare— and unlike word n-grams, which can occur with any frequency— lexical bundles are diffused throughout the language, occurring at least ten times per million words, and in many cases much more frequently (Biber et al., 1999: 989).1 Because of their frequency, lexical bundles are regarded as “discourse framing devices”: sequences of words that function as connective tissue in organizing discourse, expressing stance, or conveying referential status (Biber, 2006: 174).

While much of this ground-breaking research has focused on register—i.e., on differences in the use of multi-word sequences in various discourse contexts (like conversation vs. academic prose)—surprisingly little attention has been paid to the role of bundles in fiction. Biber et al. (1999) do not discuss results for fiction in their work, focusing instead on differences between academic prose and conversation (cf. also Conrad and Biber, 2004). Michaela Mahlberg’s corpus stylistics approach to Dickens’ fiction (2012) was pioneering in the use of lexical bundles to study fiction, but to date, no studies focusing on corpus- or register-wide trends in fiction have appeared.2 Yet the dramatic differences in the use of lexical bundles in other registers suggest that lexical bundles play an important role in building the discourse of fiction, and also that the bundles that occur in fiction will be significantly different than those occurring in other registers.

This paper analyzes the role of lexical bundles in a corpus of over 1000 novels published in Great Britain and America between 1800 and 1905. The two key contributions of the paper are: 1) to provide a taxonomy of the discourse functions of lexical bundles in nineteenth-century English and American fiction; and 2) to historicize that usage by tracking changes in our corpus over the course of the nineteenth century. We also provide some data about differences between narration and dialogue.

In expanding the unit of analysis beyond the level of the word, this paper also aims to intervene in recent methodological debates about digital humanities research on literary style. Much DH research on style in recent years—including some of the authors’ own work—has relied on a bag-of-words approach (Heuser and Le-Khac, 2012; Underwood and Sellers, 2012; for a discussion of the virtues of this approach, see Underwood, 2013). Since the terrain of higher-level lexical patterning in fiction remains under-explored, this paper contributes to the field both a methodological approach and a set of empirical results about the language of the nineteenth-century Anglo-American novel.

2. Methods

Our corpus derives from two digital fiction collections (licensed to the Stanford University Libraries) by Proquest: “Early American Fiction” (805 American novels published from 1789 - 1875; and “Nineteenth-Century Fiction” (250 British novels published from 1782-1903). To extend the American corpus’ historical scope to match that of the British corpus, we added a collection of about 325 American novels published between 1875 and 1905. We selected these texts based on their inclusion in the Annals of American Literature (Ludwig and Nault, 1989) and their availability in Project Gutenberg.

To identify bundles in a corpus with an uneven historical distribution of texts, we split each national corpus into four twenty-five year segments, creating eight sub-corpora. Each sub-corpus is derived from an identical number of words per author. Authors with fewer than 100,000 words in a particular period were not included; authors with more than this number were included by selecting 100 random slices of 1,000 words from all of their texts published in the period. Sub-corpora ranged in length from 900,000 words (U.S. publications, 1800-25) to 5.9 million words (U.S. publications, 1850-75), with a median length of 2.3 million words.

Following Biber et al. (1999), we defined lexical bundles as the most commonly occurring tri- and quad-grams in our sub-corpora, with a threshold of at least ten occurrences per one million words (frequency per million [FPM]). After tokenizing each of the eight sub-corpora, we counted the number of occurrences of each unique tri-gram and quad-gram, normalizing by the length of the sub-corpus. 3 Any tri-gram or quad-gram with a frequency above 10 FPM in any of the eight sub-corpora was considered a potential lexical bundle. Biber et al. additionally required that bundles occur in at least five different texts in the corpus, in order to guard against the possibility of individual authorial or textual effects (991). Similarly, we excluded from our list of bundles those that occurred in fewer than three unique authors, so as to exclude idiosyncratic stylistic habits, as well as bundles containing character names or other novel-specific traits. 4

We manually created an interpretive typology of the most frequent lexical bundles: the 150 most frequent tri-gram bundles (all with a median FPM across sub-corpora above 31), and the 240 most frequent quad-gram bundles (all with a median FPM across sub-corpora above 13). By looking at randomly-selected examples from the sub-corpora, each of these lexical bundles was annotated for its apparent function within fictional discourse. For example, “there was a” (5th most frequent tri-gram bundle, with a median FPM of 184) was annotated as “expletive”: grammatically, “expletives” are phrases of the form [“there” or “it” + to be], and within fiction, they provide a means by which the existence or effect of something can be easily introduced. 5

Finally, because corpus linguistics research has shown dramatic differences in lexical bundles across oral and written registers, we separately tracked their frequency in the narration and dialogue portions of our texts. To separate dialogue from narration, we used a tool developed by Grace Muzny at Stanford University. For this task we used a slightly reduced version of our corpus, which we curated by hand to ensure proper typographic markings of dialogue and thus a high precision and recall for the dialogue separation. We then replicated the corpus design described above, creating eight sub-corpora for each register, dialogue and narration. In this case, however, the periods are of twenty-year increments, from 1825 to 1905, due to the paucity of typographically well-formatted novels previous to 1825; also, each author contributes not 100,000 but 50,000 words to a particular sub-corpus, and authors with fewer than this number are not included in the sub-corpus.

3. Results

Due to constraints of space, we can provide here only an overview of our findings in each area.

1. The function of lexical bundles in nineteenth-century fiction

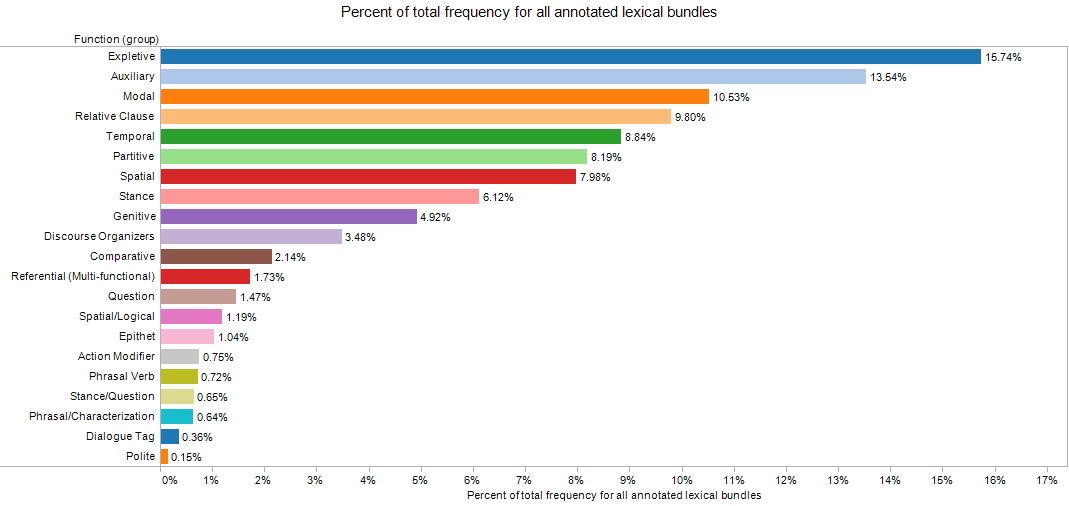

From our annotations (see “Methods” above), the most frequently-occurring bundles in fiction have one of the following functions:

- Expletive (there was a, it was a, there was no, it was not, and there was)

- Auxiliary forms (i do not, i did n’t, he did not, he had been)

- Modal forms (i could not, would have been, i ca n’t, as if he)

- Relative clause markers (that he had, that he was, which he was, that she was)

- Temporal markers (for a moment, as soon as, the first time)

- Partitive constructions (one of the, part of the, some of the)

- Spatial markers (out of the, at the door, in the house)

- Stance markers (do n’t know, i am sure, to be sure, seemed to be)

- Of-genitive (the name of; the voice of; the heart of; the hands of)

- Discourse organization markers (in spite of, as to the, in order to)

The discursive mechanisms and requirements of fiction are immediately discernable in this ranked typology, especially when compared to prior work on lexical bundles in other discursive contexts. The prominence of expletives in fiction, for example, seems particularly significant, as they condense a fundamental gesture of storytelling into a phrase: once upon a time, there was a... Expletives function in our corpus as a means of positing and sustaining a fictional ontology: it was the best of times, it was the worst of times. Similarly, the prevalence of temporal and spatial markers ( as soon as, in front of) help perform another fundamental task of fictional narration, that is, maintaining a complex and evolving network of persons, objects and events in their changing relationships to one another.

2. Historical behavior of lexical bundles

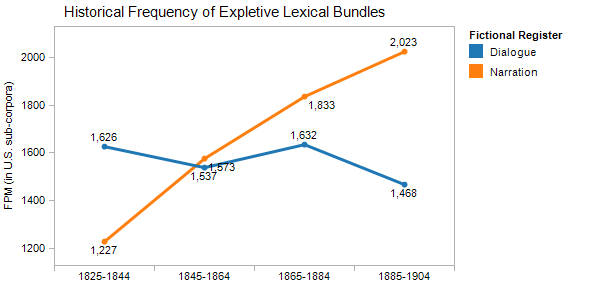

On the whole, the historical trends we find in the use of lexical bundles suggest an increasing specialization of certain narrative functions over the course of the century, especially in the language of dialogue and its narrative orchestration. For example, the most frequent functional type of lexical bundle—the “expletive” bundles described above, like “ there was a”—are actually more frequent in dialogue than in narration earlier in the century, but are then increasingly adopted by fictional narrators as part of their machinery for coordinating the existence of fictional objects (see Figure 2).

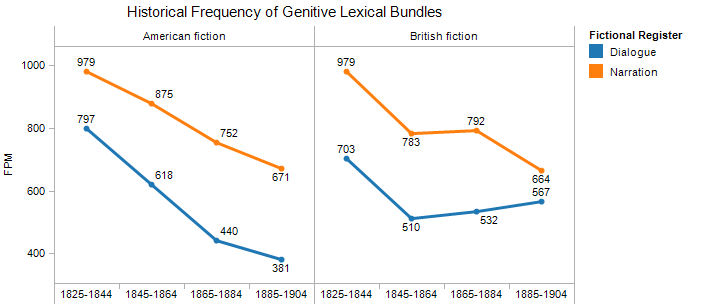

We also see evidence of historical changes that do not depend on internal register differences in fiction (narration vs. dialogue). Particularly striking is the general decline in the use of of-genitives in both narration and dialogue, in both British and American fiction (see Figure 3)—presumably replaced by the more concise Saxon genitive (’s) or by noun phrases (as in the center of the city vs. the city center). This may be an instance of a broader shift towards more informal, concise diction as the nineteenth century progresses, since the Saxon genitive and such noun phrases privilege efficiency of expression over the rhythmical advantages of the of-genitive.

Finally, we find some key differences in the use of bundles between dialogue and narration, largely having to do with national differences in colloquial expressions. In American dialogue, for example, over the course of the century we find an increased use of going-to future forms (are going to; am going to; going to do; are you going; going to be), along with an increase in colloquial discourse markers (sort of thing; kind of a; all the time). In the British dialogue corpus, similarly, we find a decrease in formal and polite phrases over time (to be sure; i have no doubt; my dear sir; depend upon it; god bless you; as you please; by the bye; the honour of), and a concurrent rise in more informal modern phrases (in spite of; at any rate; here and there; now and again). Taken together, such trends suggest that this shift towards more informal bundles is particularly concentrated in fictional dialogue.

- Biber, D. and Conrad, S. (1999). Lexical bundles in conversation and academic prose. In Out of Corpora: Studies in Honor of Stig Johansson, (Ed) Hilde Hasselard, Signe Oksefjell. Rodopi, Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp: 181–89.

- Biber, D., et al. (2003). Lexical bundles in speech and writing: An initial taxonomy. In Wilson, A. et al., Corpus Linguistics by the Lune. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 71–92.

- Biber, D., et. al. (1999). The Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Longman.

- Culpeper, J. (2012). Early Modern English Dialogues: Spoken Interaction as Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heuser, R. and Le-Khac, L. (2011). Learning to Read Data: Bringing out the Humanistic in the Digital Humanities. Victorian Studies, 54(1): 79-86.

- Ludwig, R. and Nault, C. (1989). The Annals of American Literature, 1602-1983. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mahlberg, M. (2012). Corpus Stylistics and Dickens’ Fiction. New York: Routledge.

- Underwood, T. and Sellers, J. (2012). The Emergence of Literary Diction. Journal of Digital Humanities, 1(2).

- Underwood, T. (2013). Wordcounts are amazing. The Stone and the Shell, 20 February. Retreived from: <http://tedunderwood.com/2013/02/20/wordcounts-are-amazing/>.

In stylometry, there has been lively debate about the use of n-grams for authorship attribution. Our study differs in focusing on very common n-grams (i.e., on lexical bundles) rather than the rare n-grams studied by Vickers (2011), and it does so not for the purposes of authorship attribution, but rather to identify how fiction’s most common lexical bundles may have evolved over time, and may have done so differently in narration and in dialogue.

Jonathan Culpeper’s 2012 book is another recent study that uses bundles to study literary texts, but Culpeper’s object of inquiry is the early modern English dialogue, not the novel.

Departing from Biber et al., we decided to tokenize contractions as separate words (with “won’t” becoming “wo” + “n’t”), in order to place bundles involving contractions in direct comparison with their uncontracted equivalents (“i wo n’t” and “i will not” being both tri-gram bundles).

Biber and Conrad (1999) argue, and we agree, that lexical bundles often serve as mechanisms for bridging syntactic and semantic units. Accordingly, we allow lexical bundles to cross punctuation as well as clause and phrase boundaries.

For example, in the 1835 novel by William Gilmore Simms, The Partisan: A Tale of the Revolution: “but there was a reckless audacity in his replies to the friendly suggestions of the landlord, which half-frightened the latter personage out of his wits.”