Authors: Eetu Mäkelä, Thea Lindquist, Eero Hyvönen

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: contextualization, linked data, close reading, uses of GLAM data

CORE - A Contextual Reader based on Linked Data

1. Motivation

In a relatively recent study on the needs of humanities faculty and students in using digital sources (Lindquist and Long 2011), two major issues were identified: 1) locating data relevant to a topic when online collections are distributed across institutions and systems; and 2) being able to explore the items found in context. In addition, problems were identified with crossing language barriers and with ambiguities and variants in names.

The CORE contextual reader is an application that uses natural language processing and Linked Data (Heath and Bizer 2011) techniques to address these issues in the context of close reading of primary source material 1. Particularly, the CORE application has been designed to improve the user reading experience with texts in a domain not entirely familiar to them. Examples of this situation include a history student approaching a new topic through primary sources, or a layperson trying to make sense of law texts.

2. The CORE user interface

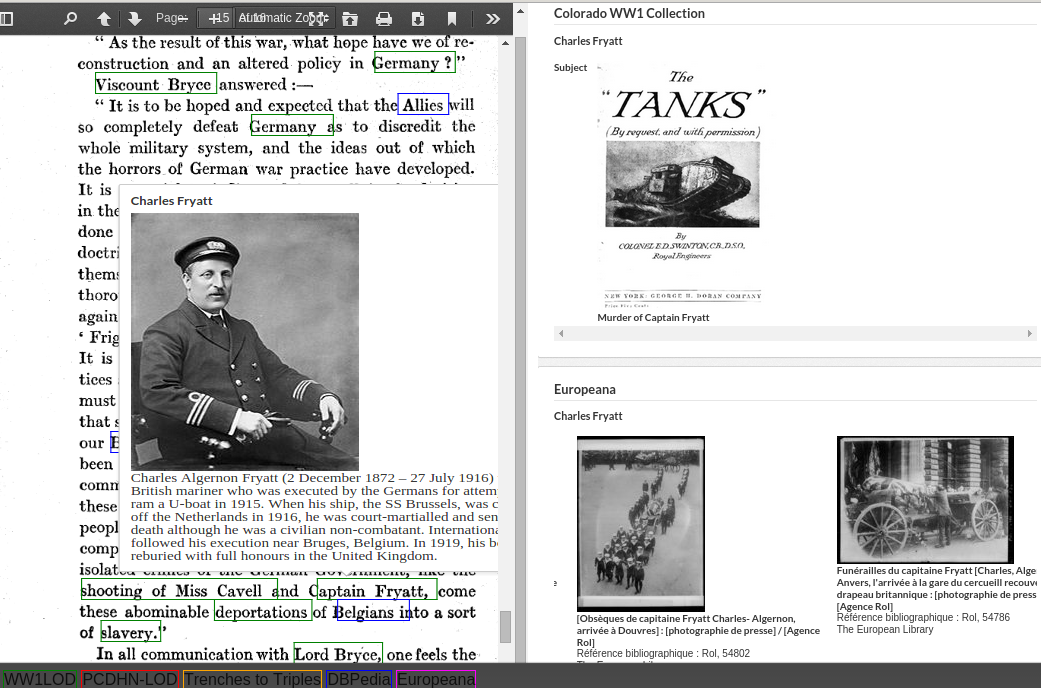

CORE supports contextualization in and understanding of unfamiliar documents by utilizing Linked Data reference vocabularies and datasets to identify entities in any PDF file or web page. For each discovered entity, CORE can then present configurable information sourced from these reference datasets on a mouse-over inside the web browser being used to read the document. Figure 1 shows this functionality in the context of reading a primary source document dealing with the First World War. The document, a scanned PDF, is shown in the interface on the left-hand side. Colored boxes highlight all of the entities identified by CORE. Here, the user has moused over “Captain Fryatt”, and the interface has brought up his picture and a short biography. Other examples of contextual information shown are word definitions for domain-specific vocabulary, maps showing the geographical context of unfamiliar places mentioned, and so on.

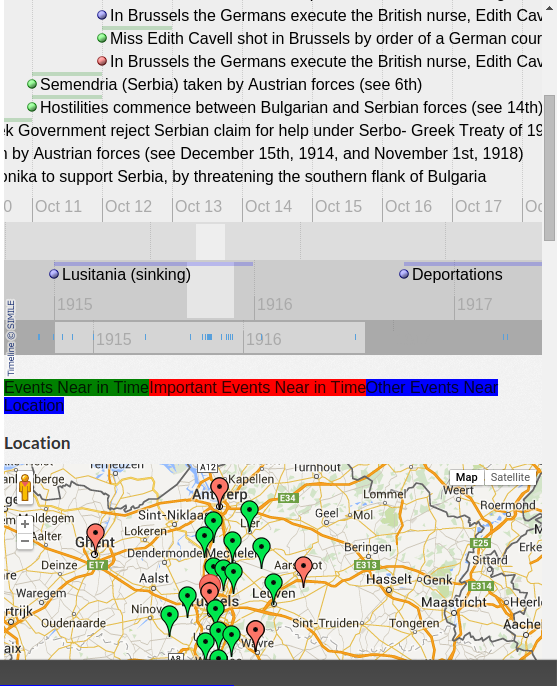

If further information is needed, an entity can be clicked on to load more information and context into the pane on the right-hand side of the reader. In this pane, contextualization is further supported by visualizations, for example, locating the entity of interest temporally on a timeline and geographically on a map. Figure 2 shows these visualizations for an identified event, in this case the execution of Nurse Edith Cavell by the Germans in Belgium during WW1. At the top of the pane, the event is contextualized temporally among other war events. These are color-coded to differentiate: 1) important top-level wartime events sourced from the Imperial War Museum, 2) all events happening in the same timeframe, and 3) other wartime events happening nearby. Below the timeline, all of these events are presented on a map to give a geographical perspective. Clicking on any of the entities visualized loads the information pertaining to that entity into the contextualization pane, allowing further navigation of the context.

In addition to providing more nuanced context, the right-hand pane of CORE also facilitates serendipitous discovery of further related content. Using the configured Linked Data vocabularies, CORE is able to extract relevant search terms for an entity of interest. These search terms can then be used to discover related content from configured endpoints, even if they support only simple text searches. In Figure 1, this functionality is seen on the right-hand side of the user interface. First, formally encoded metadata brings in another relevant primary source from the University of Colorado Boulder’s (CU-Boulder) WWI Collection Online 2. Images of the burial of Captain Fryatt from Europeana 3, on the other hand, are found not through formally encoded keywords, but rather a match on his name that appears in the textual description of the images.

Among the extracted terms used in the query are multilingual labels for places, variant names for actors and events, etc. Leveraging these terms enables CORE to cross language barriers and handle naming variations. To improve recall even further, the search term extraction can be configured to include terms for related entities, such as the actors participating in an event or the names of all villages in a particular municipality under investigation.

Because CORE is able to dynamically process most HTML and PDF content, any linked resource can be loaded into the contextual reader by clicking on it. This function facilitates endless browsing on a topic through thematic and contextual connections, regardless of from where the linked material comes.

3. System demonstrators

In contrast to most other similar systems, a CORE instance can relatively easily (and always should be) configured for a particular domain, thus ensuring the contextual information provided is actually useful and interesting to the end-user.

To provide its services, CORE makes use of dynamic, configurable entity recognition, in which modular lexical analysis services are combined with SPARQL queries 4. This allows multilingual entity recognition against any vocabulary stored at a Linked Data endpoint. A configuration therefore consists of tuning the lexical analysis service to a particular domain and set of languages, as well as defining the endpoints and queries to be used in bringing in contextual information and related resources.

While in future the application is intended to be fully configurable using a web user interface, currently new instances must be configured from the source code, released under the MIT open source license at http://github.com/jiemakel/core/. Thus far, three different demonstrators have been created 5.

The first of these is the contextual reader for First World War primary sources available at http://demo.seco.tkk.fi/ww1/. For vocabularies, it draws on the WW1LOD dataset (Mäkelä et al. 2015), the vocabularies of 1914–1918 Online 6, the Europeana 1914–1918 7 thesaurus, the Out of the Trenches (Pan-Canadian Documentary Heritage Network 2012) and Trenches to Triples 8 vocabularies, and DBpedia (Lehmann et al. 2015). Repositories used for sourcing related content are CU-Boulder’s WWI Collection Online, WW1 Discovery 9, Europeana, the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) 10, and The European Library (TEL) 11.

To further demonstrate multilingual support as well as support for inflected languages, a second contextual reader has been configured to support the study of ancient Roman sources, be they translated into English or still in the original Latin. This installation is available at http://demo.seco.tkk.fi/ancore/. Here, ancient place names are located on maps through the Pleiades gazetteer of ancient places 12, while information on entities like people and mythical characters mentioned in the texts is sourced from the English and Latin DBpedias. Targeted repositories are the Perseus Catalog 13, the various Pelagios datasets 14, and again Europeana, DPLA, and TEL.

The final demonstrator, aimed at supporting the reading of legal documents in the highly inflected language of Finnish, is available at http://demo.seco.tkk.fi/laki/. In this case, the documents are drawn from, for example, the consolidated legislation 15 and the precedents of Finnish supreme courts 16 published by the Finnish Ministry of Justice. In addition to linking these distributed resources to one another, the application is able to bring in news articles 17 dealing with laws of interest published by Edita Publishing.

When reading documents containing precise legal terminology, the reader is supported by definitions from the legal terminology section of the Bank of Finnish Terminology in Arts and Sciences 18, the Asseri vocabulary of the Ministry of Justice, the Edilex legal vocabulary from Edita, the Finnish law vocabulary from Talentum Publishing, and the legal terminology section of the Finnish DBpedia. In addition to Finnish, this reader has also been configured with limited support for Swedish, as Finland is a bilingual country.

4. Conclusions and future work

The CORE contextual reader clearly demonstrates the potential of utilizing Linked Data vocabularies to bridge institutional silos and language barriers, even in situations where the structured metadata of the corresponding databases is lacking. On the other hand, the core mission of the tool is to support contextualization and understanding. While initial experience points both to significant overall support, as well as a marked increase in support with regard to less domain-configured alternatives (Csomai and Mihalcea 2007; Olango, Kramer, and Bouma 2009), a formal user evaluation of the reader remains to be conducted. This will be the natural next step for the project, and plans for testing the WW1 version of the reader are already underway.

At the same time, the CORE reader is currently seeing uptake in new contexts, most notably a project to unify disparate material related to the Finnish view of the Second World War (Hyvönen et al. 2015). Supporting these new contexts may require further development of components of the reader. For example, the Second World War material under study contains multiple distinct places and people with the same names. To properly handle these would require better support for disambiguation in the entity recognition component of the reader.

- Csomai, A. and Mihalcea, R. (2007). Linking Educational Materials to Encyclopedic Knowledge. Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education: Building Technology Rich Learning Contexts That Work. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 557–59.

- Dzbor, M., Motta, E. and Domingue, J. (2007). Magpie: Experiences in supporting Semantic Web browsing. Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web.

- Heath, T. and Bizer, Ch. (2011). Linked Data: Evolving the Web into a Global Data Space. Synthesis Lectures on the Semantic Web. Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

- Hyvönen, E. et al. (2015). Second World War on the Semantic Web: The WarSampo Project and Semantic Portal. Proceedings of 14th International Semantic Web Conference 2015 (ISWC 2015), Posters and Demos. Forthcoming. Bethlehem, PA, USA: CEUR-WS Proceedings.

- Lehmann, J. et al. (2015). DBpedia - A large-scale, multilingual knowledge base extracted from Wikipedia. Semantic Web, 6(2): 167–95.

- Lindquist, T. and Long, H. (2011). How can educational technology facilitate student engagement with online primary sources?: A user needs assessment. Library Hi Tech, 29(2): 224–41.

- Mäkelä, E. (2014). Combining a REST Lexical Analysis Web Service with SPARQL for Mashup Semantic Annotation from Text. Proceedings of the ESWC 2014 demonstration track, Springer-Verlag.

- Mäkelä, E. et al. (2015). World War 1 as Linked Open Data. Submitted for review.

- Olango, P., Kramer, G. and Bouma, G. (2009). TermPedia for interactive document enrichment using technical terms to provide relevant contextual information. International Multiconference on Computer Science and Information Technology, 2009. IMCSIT ’09, pp. 265–72.

- Pan-Canadian Documentary Heritage Network (2012). PCDHN Linked Open Data Visualization “Proof-of-Concept”. Tech. rep.