Authors: Anthony Durity, Gabriela Vulcu, Georgeta Bordea, James O'Sullivan, Jasenka Eva Jones

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: topic modeling, corpus, philosophy, categories, taxonomy

The Categories of Philosophy in the Digital Era

1. Knowledge Representation

The research we present is a digital reworking of the categories. This research forms part of a larger work which explores the impact of computational methods on philosophy. Nearly 40-years-ago Aaron Sloman anticipated this Computer Revolution in Philosophy (Sloman, 1978). This revolution is as yet not fully under way, we would argue, at least not to the same extent that it is currently transforming the humanities and has already transformed the sciences. Our research adds momentum.

A distinction must be made between the general notion of category in philosophy and the top-level categories of metaphysics. When we refer to the categories of virtue of vice, for instance, it is to the general notion of category to which we refer. When we refer to the ontologies of Aristotle, Kant, Peirce, Whitehead, or whoever, it is to the top-level categories that we refer. Every object/entity there is, without exception, participates in at least one of these top-level categories because these categories indicate universal properties. Properties such as: quality, substance, modality, form, and so on. C. S. Peirce arguably took these investigations to their logical conclusion with his triad of logical terms: firstness, secondness, thirdness. John F. Sowa in Knowledge Representation (Sowa, 2000) presents a historical account of this philosophical activity and its connections with software modelling, we regard our research is a continuation of Sowa's investigations.

Saffron (Bordea, 2013) is a domain modelling research tool that uses novel natural language parsing and taxonomic techniques. Specifically, it performs domain adaptive extraction of topical hierarchies. Saffron was conceived and is being developed at the Insight Centre for Data Analytics in the National University of Ireland, Galway.

PACT.x (Durity, 2015) is a purpose-built corpus of philosophical texts, these are stored in plain text with their associated metadata and they reflect 2500 years of mainly Western thought, from Plato's Symposium to Wittgenstein's Tractatus. PACT.x was conceived and is being developed at the Digital Arts and Humanities program in University College Cork, Ireland.

We arrive at a digital reworking of the categories in a number of algorithmic steps.

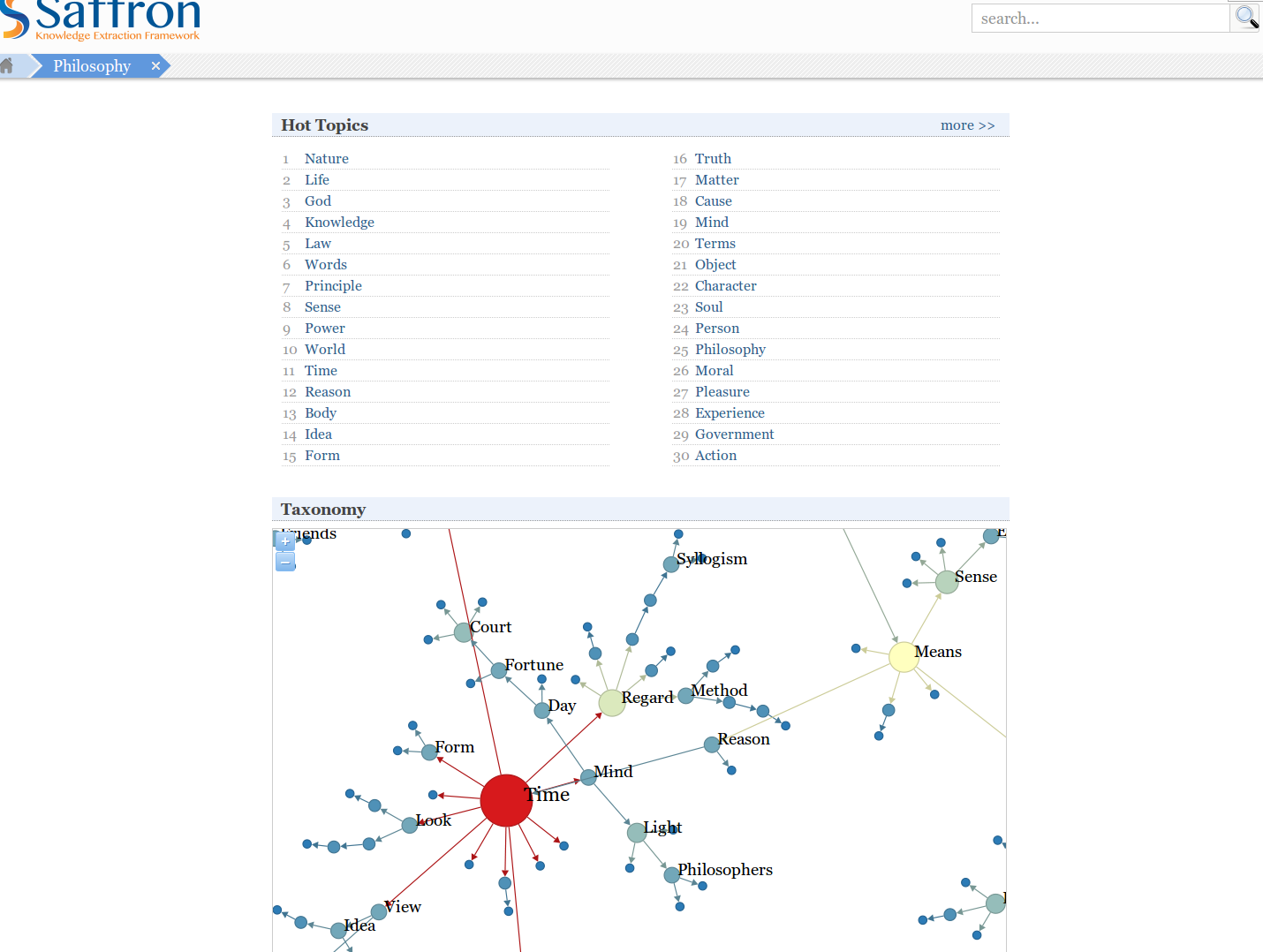

(1) By performing a semantic-based analysis of the PACT.x corpus using Saffron we obtain result set α, Rα, which comprises a sequence of terms, Sα, and related taxonomy, Tα, of philosophical concepts (Vulcu, 2015) and their corresponding visualisation - Figure 1. Sequence Sα is ordered by a weighted combination of frequency and coherence, meaning frequency of occurrence of a word within the corpus coupled with terms that contain a word from the domain model, and terms that appear in the context of a word from the domain model. The structure and relation of the topics in taxonomy Tα are drawn from result set Rα. The directed edges of the graph are constructed using the broader/narrower than relation from WordNet ‡ and the graph is pruned using the ChuLiu/Edmonds algorithm resulting in a directed acyclic graph.

The first 30 terms in sequence α are:

| 1 Nature | 16 Truth |

| 2 Life | 17 Matter |

| 3 God | 18 Cause |

| 4 Knowledge | 19 Mind |

| 5 Law | 20 Terms |

| 6 Words | 21 Object |

| 7 Principle | 22 Character |

| 8 Sense | 23 Soul |

| 9 Power | 24 Person |

| 10 World | 25 Philosophy |

| 11 Time | 26 Moral |

| 12 Reason | 27 Pleasure |

| 13 Body | 28 Experience |

| 14 Idea | 29 Government |

| 15 Form | 30 Action |

(2) We Iterate through each of the terms in result set α in turn and query the open knowledge graph Wikidata 1 to perform further analysis. By tracing the compositional relationship properties (instance-of, subclass-of, part-of) of each term we infer the compositional structure of these concepts and obtain ultimately another sequence, Sβ, and related taxonomy, Tβ. The list of topics that is sequence Sβ is more or less identical to sequence Sα save for disambiguation and completeness. Note that taxonomy Tβ differs from taxonomy Tα in that it reflects the mereological structure of Wikidata rather than WordNet.

(3) Taxonomy Tβ is then divided into two parts using a heuristic method: the base taxonomy, Tγ, which comprises the most abstract part, and superstructure which comprises the rest.

Taxonomy Tγ is the digital reworking of the categories.

2. Critical Assessment in Context

We compare taxonomy γ with the traditional categories of philosophy to see how the singular vision of individuals (Aristotle, 1938; Kant, 1787, for instance) differs from what may be viewed as a complex adaptive system (WordNet and Wikidata). To clarify, the idea here is to contrast the semi-isolated contemplation of individuals from different eras with the distillation of the organic collective behaviour of billions of wiki edits. In what way does a digitally generated ontology differ from the standard hand-built ones? For a contrasting approach see the recent theoretical work Foundations of an Ontology of Philosophy (Grenon and Smith, 2011) with attendant Web Ontology Language applied work Philosophy Ontology (Grenon, 2007)

We validate resultset α against authoritative philosophical reference works such as The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (Blackburn, 2008), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Craig, 1996), and so on. In this way we are able to understand how a distant reading (to use a term that has almost become a genericized coinage) of topics by machine algorithms compares to professional reference works. Is it possible that topics that philosophers have touched on down through the ages, as highlighted by the machine, haven't gotten the attention they deserve? If so, why? Is it possible that there are topics which are considered important enough to gain a reference entry that have been overlooked by the machine? Again, what could be the reason? Because the topics in resultset α are ordered by frequency we now have a rough quantitative measure of the relative usage of different philosophical concepts which perhaps can be used as a proxy for their relative human significance; reference works obviously arrange entries in alphabetical order having no other metric.

Our research indicates that novel computational methods may be brought to bear on the task of philosophy. It suggests a radically different route than that taken by others, such as that of modelling the formal systems discussed within philosophical works, as exemplified by The Philosophical Computer (Grim, Mar, and St. Denis, 1998). It suggests also that we should take a sustained look beyond the more, if we may say, pedestrian use of the computer as an educational and communication tool as discussed, for example, in Cyberphilosophy (Moor and Bynum, 2002).

Though some way off from becoming part of the standard philosophical curriculum the investigations we have undertaken indicate further avenues of fruitful research and hint at future novel results once the methods have been refined through third-party experimentation, replication, and feedback.

- Aristotle. (1938). The Organon. In H. P. Cooke, H. Tredennick, and E. S. Forster, (Eds.). Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University press; W. Heinemann Ltd.

- Blackburn, S. (Ed.). (2008). The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bordea, G. (2013). Domain Adaptive Extraction of Topical Hierarchies for Expertise Mining. PhD dissertation. Retrieved from http://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/xmlui/handle/10379/4484

- Craig, E. (Ed.). (1996). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. Retrieved 5 March 2016, from https://www.rep.routledge.com/

- Durity, A. (2015). Philosophy Archive of Clear Text, PACT.x. Corpus. http://dh.ucc.ie/corpus-builder/texts.xml

- Grenon, P. (2007). Philosophy Ontology. Web Ontology Language File. (5 March 2016)http://ontology.buffalo.edu/philosophome/pdcphilontology-v1.owl

- Grenon, P., and Smith, B. (2011). Foundations of an Ontology of Philosophy. Synthese, 182(2): 185–204.

- Grim, P., Mar, G., and St. Denis, P. (1998). The Philosophical Computer: Exploratory Essays in Philosophical Computer Modeling. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Kant, I. (1787). The Critique of Pure Reason. In M. D. Meiklejohn, Trans, Raleigh, N.C.: Alex Catalogue.

- Moor, J. H., and Bynum, T. W. (2002). Cyberphilosophy: The Intersection of Philosophy and Computing. Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons.

- Sloman, A. (1978). The Computer Revolution in Philosophy: Philosophy, Science, and Models of Mind. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press.

- Sowa, J. F. (2000). Knowledge Representation: Logical, Philosophical, and Computational Foundations. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole.

- Vulcu, G. (2015). Philosophy Texts - One Word. (31 October 2015) http://140.203.155.226:8000/philosophy_one_word/

https://wordnet.princeton.edu/

“WordNet® is a large lexical database of English. Nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs are grouped into sets of cognitive synonyms (synsets), each expressing a distinct concept. Synsets are interlinked by means of conceptual-semantic and lexical relations.”

https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Wikidata:Main_Page “Wikidata is a free linked database that can be read and edited by both humans and machines.” “Wikidata acts as central storage for the structured data of its Wikimedia sister projects[…]” Wikidata is a triplestore. A triplestore is a database of semantic web triples, each with the form: subject, predicate, object. It is no coincidence, we suggest, that the ultimate store of structured data that has evolved on the web shares the same form as Peirce's triad of logical terms.