Authors: Maciej Piasecki, Tomasz Walkowiak, Maciej Eder

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: NLP, stylometry, text classification, web-based system, distributed processing

WebSty – an Open Web-based System for Exploring Stylometric Structures in Document Collections

1. Introduction

Computer-assisted text analysis is now witnessing the phenomenon of ever-growing computer power and, more importantly, an unprecedented aggregation of textual data. Certainly, it gives us an unique opportunity to see more than our predecessors, but at the same time it presents non-trivial challenges. To name but a few, these include information retrieval, data analysis, classification, genre recognition, sentiment analysis, and many others. It can be said that, after centuries of producing textual data and decades of digitisation them, the scholars now face another great challenge - that of beginning to make good use of this treasure.

Generally speaking, the problem of large amounts of textual data can be perceived from at least three different perspectives. Firstly, there is a need of asking new research questions that would take advantage of thousands of texts that can be compared. Secondly, one has to introduce and evaluate statistical techniques to deal with vast amounts of data. Thirdly, there is a need of new computational algorithms that would be able to handle enormous corpora, e.g. containing billions of tokens, in a reasonable amount of time. The present study addresses the third of the aforementioned issues.

Stylometric techniques are known for their high accuracy of text classification, but at the same time they are usually quite difficult to be used by, say, an average literary scholar. In this paper we present a general idea, followed by a fully functional prototype of an open stylometric system that facilitates its wide use with respect to two aspects: technical and research flexibility. The system relies on a server installation combined with a web-based user interface. This frees the user from the necessity of installing any additional software. Moreover, we plan to enlarge the set of standard stylometric features with style-markers referring to various levels of the natural language description and based on NLP methods.

2. Multi-aspectual Document Representation

Computing word frequencies is simple for English, but relatively complicated for highly inflected languages, e.g. Polish, with many word forms, resulting in data sparseness. Thus, it might be better first to map the inflected forms onto lemmas (i.e. basic morphological forms) with the help of a morpho-syntactic tagger, and next to calculate the lemma frequencies.

Most frequent words or lemmas as descriptive features proved to be useful in authorship attribution. However, for some text types or genres they do not provide sufficient information to tell the authors apart, e.g. see (Rygl, 2014). Moreover, in other types of classification tasks, where the goal is to trace signals of individual style, literary style or gender, it usually turns out that they appear on different levels of the linguistic structures. Thus, one needs to enhance text description.

In practice, every language tool introduces errors. However, if the error level is relatively small and the errors are not systematic (i.e. their distribution is not strongly biased), than the results of such a tool can be still valuable for stylometric analysis. Bearing this in mind, we have evaluated a number of language tools for Polish, and selected types of features to be implemented:

- length of: documents, paragraphs or sentences (a segmentation tool),

- morphological features

- word forms or tokens and punctuation marks,

- pseudo-suffixes (last several letters),

- lemmas (from WCRFT2 morpho-syntactic tagger for Polish (Radziszewski, 2013))

- grammatical classes

- 35 grammatical classes defined in the tagset (Szałkiewicz and Przepiórkowski, 2012) of the Polish National Corpus (Przepiórkowski et al., 2012), e.g. pseudo-past participle, non-past form, ad-adjectival adjective; recognised by WCRFT2,

- parts of speech (by grouping grammatical classes),

- grammatical categories, e.g. gender, number, person, etc.; (WCRFT2),

- sequences

- lemma sequences (e.g. potential collocations),

- sequences of grammatical classes (bigrams or trigrams - hints about the grammatical structures),

- semantic features

- semantic Proper Name classes – recognised by a Named Entity Recogniser Liner2 (Marcińczuk, 2013),

- lexical meanings – represented by synsets in plWordNet (the Polish wordnet); assigned by Word Sense Disambiguation tool WoSeDon (Kędzia, et al., 2015)

- generalised lexical meanings – more general meanings from plWordNet, e.g. an animal instead of a cheetah,

- formalised concepts from a formal ontology SUMO that plWordNet is mapped to,

- lexicographic domains from wordnet.

Semantic features go beyond a typical stylometric description, but allow for crossing borders between the style and the content description.

There are no features overtly describing the syntactic structure, as the available parsers for Polish express too high level of errors. The set of features can be further expanded by user-defined patterns expressed in the WCCL language (Radziszewski et al., 2011) that can be used to recognise binary relations between words and their combinations.

WebSty allows for testing the performance of the aforementioned features in different stylometric tasks, several case-studies will be presented on a set of Polish novels.

3. Processing and Results

The proposed system follows a typical stylometric workflow which was adapted to the chosen language tools and other components of the architecture (see Section 4).

- Uploading a corpus of documents together with meta-data in CMDI format (Broeder et al., 2012) from the CLARIN infrastructure.

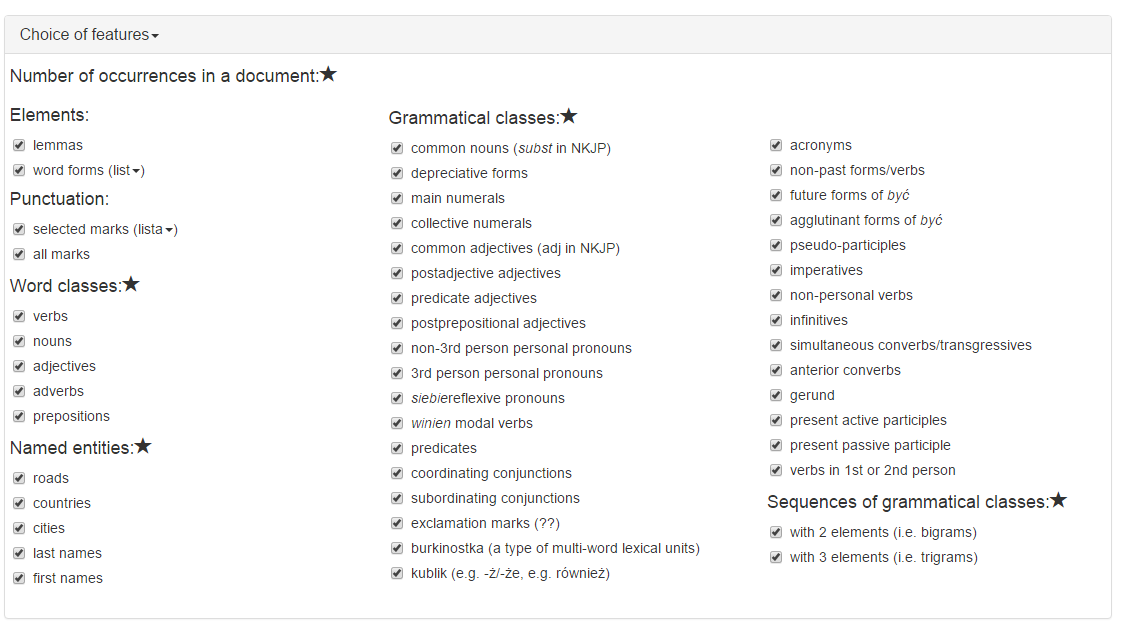

- Choosing the features for the description of documents – done by the users (see Fig. 1).

- Setting up the parameters for processing (users).

- Pre-processing texts with the help of language tools.

- Extracting the features from the pre-processed texts.

- Calculating feature values.

- Filtering and/or transforming the original feature values.

- Clustering the feature vectors representing documents.

- Extracting features that are characteristic for different clusters.

- Presenting the results: visualisation or export of data.

The step 5 can be performed as: simple counting of words or lemmas, processing and counting annotations matching some patterns or running patterns for every position in a document. This is why a dedicated feature extraction module comes into stage, namely Fextor (Broda et al., 2013).

Filtering and transformation functions can be built into the clustering packages (see below) or implemented by the dedicated systems, e.g. SuperMatrix system (Broda and Piasecki, 2013).

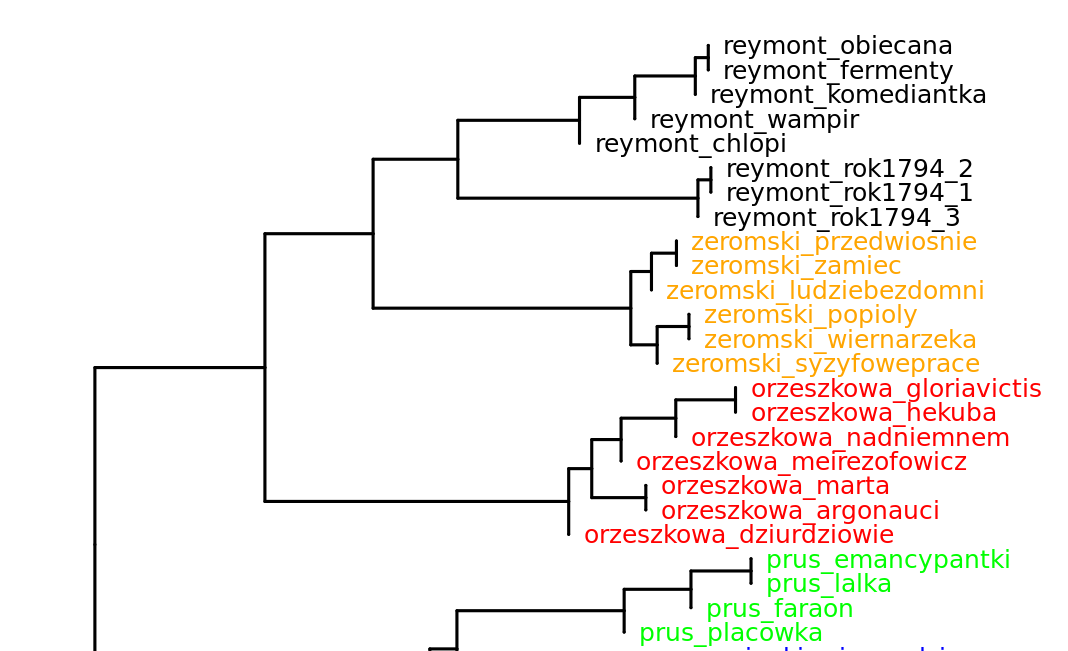

The WebSty architecture can be relatively easy adapted to the use of any clustering package. The prototype is integrated with Stylo – an elaborated clustering package dedicated to stylometric analysis, and Cluto – a general clustering package (Zhao and Karypis, 2005). Stylo offers very good visualisation functionality, while Cluto delivers richer possibilities for formal analysis of the generated clusters. The obtained results are displayed by the web browser (see Fig. 2). Users can also download log files with formalised description of the clustering results.

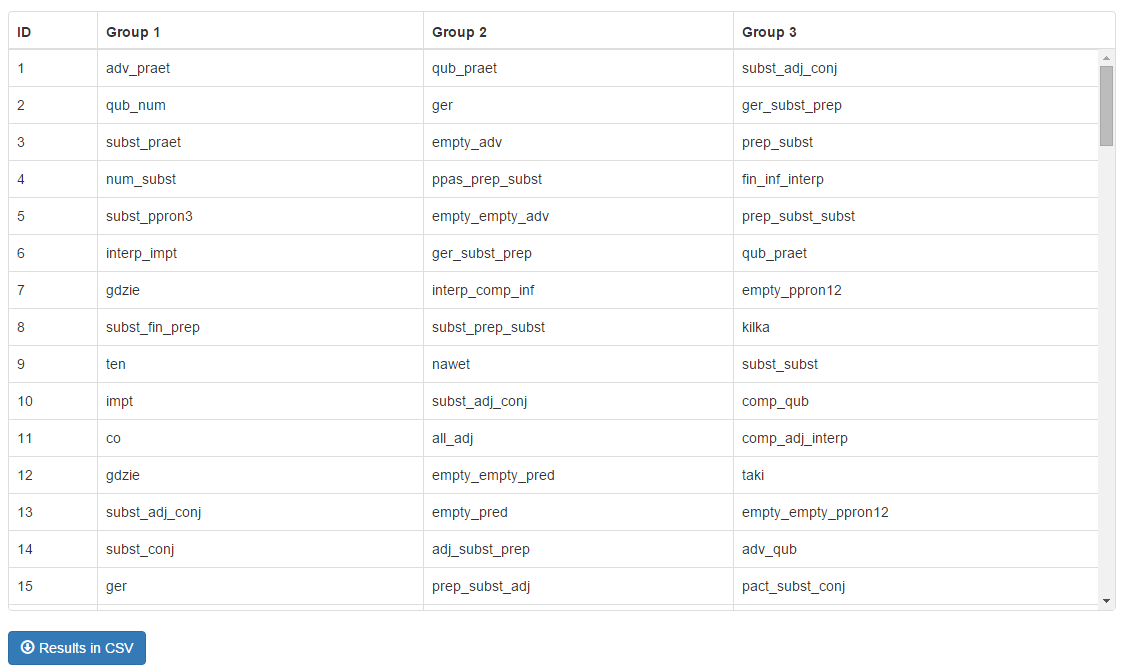

Moreover, features that are characteristic for the description of individual clusters or differentiation between clusters can be identified. Ten different functions (implemented in Weka 1 (Witten et al., 2011) and SciPy packages 2), based on mathematical statistics and information theory, are offered. The ranking lists of features are presented on the screen for interactive browsing (Fig. 3) and can be downloaded.

The system has a web-based user interface that allows for uploading input documents from a local machine or from a public repository and enables selecting a feature set, as well as options for a clustering algorithm.

4. Technical Architecture

Application of language tools is inevitably more complex than calculating statistics on the level of words or letters. Moreover, processing of Polish is mostly far more complex than English (in terms of the processing time and memory used). Thus, higher computing power and bigger resources are required. In order to cope with this, the entire analysis in WebSty is performed on a computing cluster. Users do not need to install any software - which might be non-trivial particularly in the case of the language tools. The system processes the documents using a parallel and distributed architecture (Walkowiak, 2015).

The workflow is as follows. Input documents are processed in parallel. The uploaded documents are first converted to an uniform text format. Next, each text is analysed by a part-of-speech tagger (we use WCRFT2 for Polish (Radziszewski, 2013)) and then it is piped to a name entity recognizer - Liner2 (Marcińczuk et al., 2013) in our case. After the annotation phase is completed for all texts, the feature extraction module comes into stage, i.e. Fextor (Broda et al., 2013). Clustering tools requires input data in different formats: sparse or dense matrices, text (ARRF, Cluto format) or binary files (R objects, Python objects). Thus data received from the feature extraction for each input file has to be unified and converted. The extracted raw features can be filtered or transformed by a range of methods inside the clustering packages or in a system for distributional semantics called SuperMatrix (Broda and Piasecki, 2013). Finally, the R package Stylo (Eder et al., 2013) or a text clustering tool called Cluto (Zhao and Karypis, 2005) are run to perform exploratory analysis, e.g. multidimensional scaling.

To prevent the system from overloading and long response time the input data size is limited to 20 files. However, large text collections can be processed, if they are deposited in the dSpace repository. 3 All corpora in dSpace can be annotated stored for further processing. Therefore, it is only left to run feature extraction and clustering tools inside WebSty. 4

5. Conclusion and future plans

The paper presented opened, web-based system for exploring stylometric structures in Polish document collections. The web based interface and the lack of the technical requirements facilitates the application of text clustering methods beyond the typical tasks of the stylometry, e.g. analysis of types of blogs (Maryl, 2012), recognition of the corpus internal structure, analysis of the subgroups and subcultures, etc.

The system is currently focused on processing Polish. However, as the feature representation is quite language independent, we plan to add converters for for other languages.

- Broda, B., Kędzia, P., Marcińczuk, M., Radziszewski, A., Ramocki, R. and Wardyński, A. (2013). Fextor: A feature extraction framework for natural language processing: A case study in word sense disambiguation, relation recognition and anaphora resolution. In Przepiórkowski, A., Piasecki, M., Jassem, K., Fuglewicz, P. (Eds.), Computational Linguistics: Applications, Series: Studies in Computational Intelligence, Vol. 458, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 41-62.

- Broda, B. and Piasecki, M. (2013). Parallel, Massive Processing in SuperMatrix – a General Tool for Distributional Semantic Analysis of Corpora. International Journal of Data Mining, Modelling and Management, 5(1): 1–19.

- Broeder, D., Van Uytvanck, D., Gavrilidou, M., Trippel, T. and Windhouwer, M. (2012). Standardizing a component metadata infrastructure. In: Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Doğan, M.U., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Moreno, A., Odijk, J., Piperidis, S. (Eds.), Proceedings of LREC 2012: 8th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation. European Language Resources Association (ELRA), pp. 1387-90.

- Eder, M., Kestemont, M. and Rybicki, J. (2013). Stylometry with R: a suite of tools. In: Digital Humanities 2013: Conference Abstracts. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, NE, pp. 487-89.

- Kędzia, P., Piasecki, M. and Orlińska, M. J. (2015). Word Sense Disambiguation Based on Large Scale Polish CLARIN Heterogeneous Lexical Resources. Cognitive Studies | Études cognitives, 15: 269-92.

- Marcińczuk, M., Kocoń, J. and Janicki, M. (2013). Liner2 - A Customizable Framework for Proper Names Recognition for Polish. In Bembenik, R., Skonieczny, Ł., Rybiński, H., Kryszkiewicz, M., Niezgódka, M., Intelligent Tools for Building a Scientific Information Platform, Series: Studies in Computational Intelligence, Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, 467: 231-53.

- Maryl, M. (2012). Kim jest pisarz (w internecie?). Teksty Drugie, 6: 77-100.

- Przepiórkowski, A., Bańko, M., Górski, R. L. and Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, B. (Eds.),(2012). Narodowy Korpus Języka Polskiego. Warszawa: PWN.

- Radziszewski, A. (2013). A tiered CRF tagger for Polish, In Bembenik, R., Skonieczny, Ł., Rybiński, H., Kryszkiewicz, M., Niezgódka, M., Intelligent Tools for Building a Scientific Information Platform, Series: Studies in Computational Intelligence. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 467: 215-30.

- Radziszewski, A., Wardyński, A., and Śniatowski, T. (2011). WCCL: A morpho-syntactic feature toolkit. In Habernal, I. and Matoušek, V. (Eds.), Text, Speech and Dialogue, Plzen, Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, LNAI 6836, pp. 434–41.

- Rygl, J. (2014) Automatic Adaptation of Author’s Stylometric Features to Document Types, In Sojka, P., Horák, A., Kopeček, I. and Pala, K. (Eds.), Proceedings of 17th International Conference TSD 2014. Brno, Czech Republic, LNCS 8655, Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 53-61.

- Szałkiewicz, Ł. and Przepiórkowski, A. (2012). Anotacja morfoskładniowa. In Przepiórkowski et al., pp. 59-96.

- Walkowiak, T. (2015). Web based engine for processing and clustering of Polish texts. In Zamojski, W., Mazurkiewicz, J., Sugier, J., Walkowiak, T., Kacprzyk, J., Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Dependability and Complex Systems DepCoS-RELCOMEX, Brunów, Poland, Series: Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing Springer, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 515-22.

- Witten, I. H., Frank, E. and Hall, M. A. (2011). Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques, Third Edition. Series in Data Management Systems, Morgan Kaufmann.

- Zhao, Y. and Karypis, G. (2005). Hierarchical Clustering Algorithms for Document Datasets. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 10(2): 141-68.

http://www.cs.waikato.ac.nz/ml/weka/

http://www.scipy.org/

http://ws.clarin-pl.eu/demo/cluto2.html