Authors: Akihiro Kawase

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: Traditional Japanese folk songs, regional classification, musical schema, tetrachord theory

Regional Classification of Traditional Japanese Folk Songs from the Chugoku District

1. Introduction

This study aims to grasp the regional differences in the musical characteristics inherent in the traditional Japanese folk songs of the Chugoku district (the westernmost region of Japan’s largest island of Honshu) by extracting and comparing the characteristics of each area by conducting quantitative analysis in order to promote digital humanities research on traditional Japanese folk songs.

We have sampled and digitized the five largest song genres within the music corpora of the Nihon Min’yo Taikan consisting of 1,794 song pieces from 45 Japanese prefectures, and have clarified the following three points by extracting and comparing their respective musical patterns (Kawase and Tokosumi 2011): the most important characteristics in the melody of Japanese folk songs is the transition pattern, which is based on an interval of perfect fourth pitch; regionally adjacent areas tend to have similar musical characteristics; and the differences in the musical characteristics almost match the East-West division in the geolinguistics or in the folkloristics from a broader perspective.

However, to conduct more detailed analysis in order to empirically clarify the structures by which music has spread and changed in traditional settlements, it is necessary to expand the data and do comparisons based on the old Japanese provinces (ancient administrative units that were used under the ritsuryo system before the modern prefecture system was established).

2. Procedure

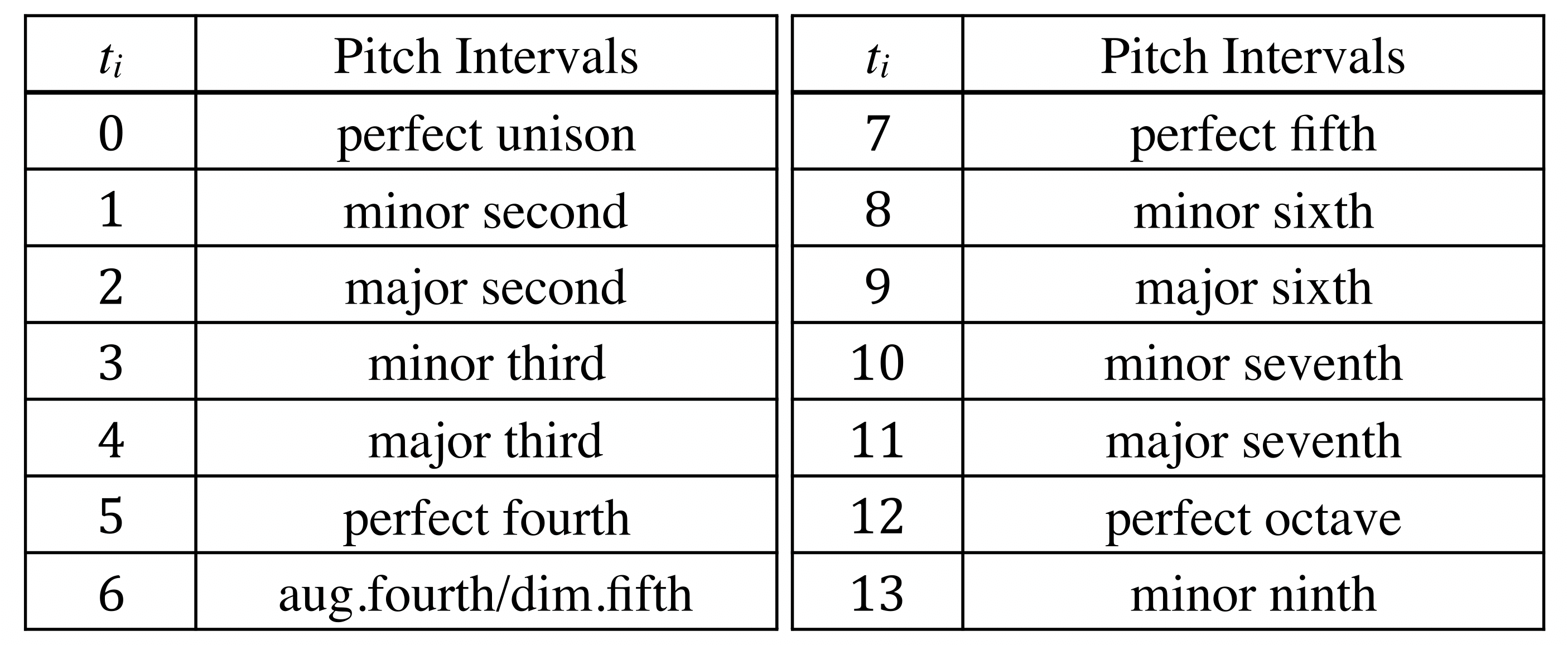

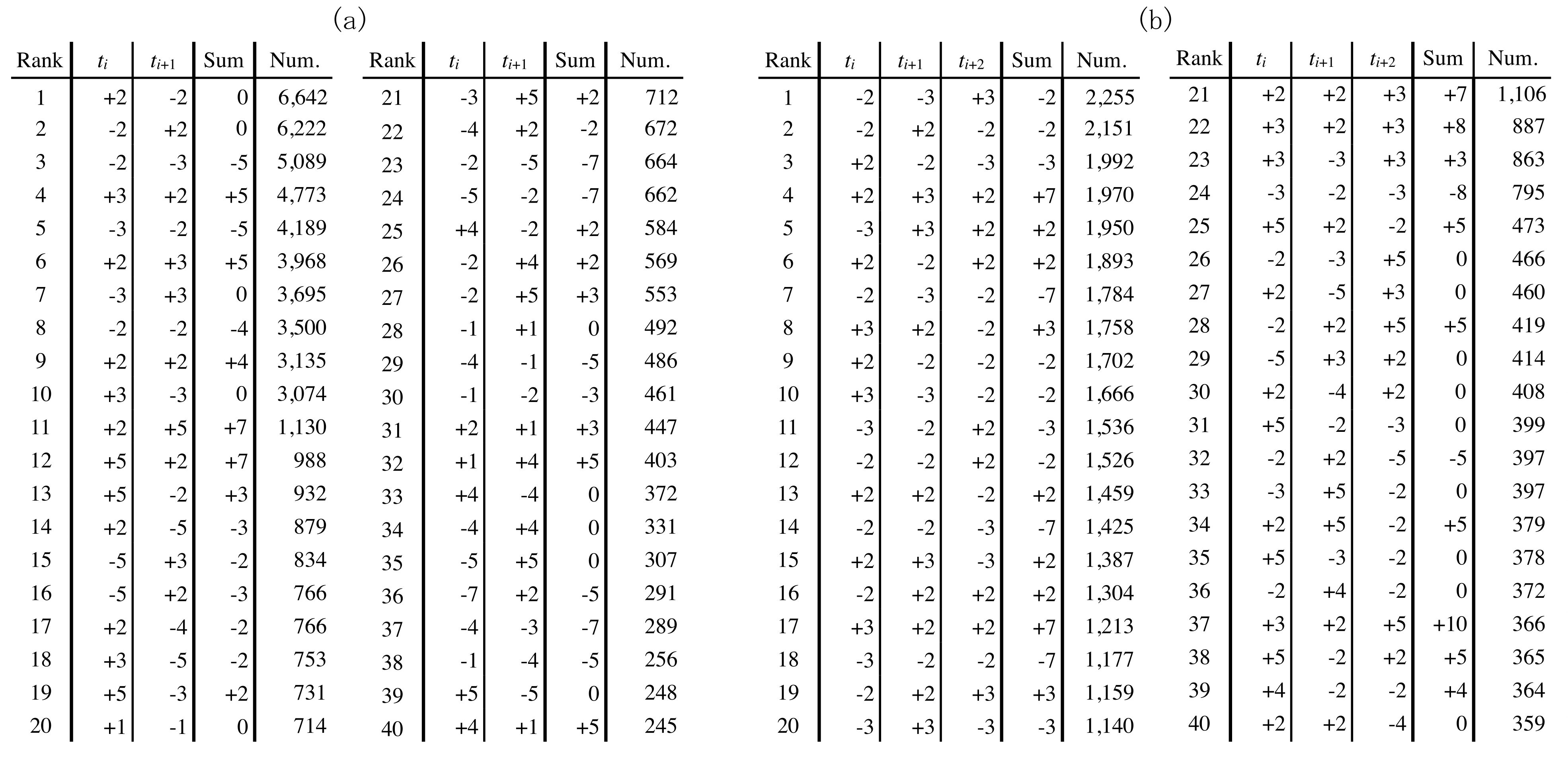

In order to digitize the Japanese folk song pieces, we generate a sequence of notes by converting the music score into MusicXML file format. We devised a method of digitizing each note in terms of its relative pitch by subtracting the next pitch height for a given MusicXML. It is possible to generate a sequence T that carries information about the pitch to the next note: T = ( t 1, t 2, … , t i, …, t n). An example of the corresponding pitch intervals for t i can be written as shown in Table 1. We treat sequence T as a categorical time series, and execute n-gram analysis by conducting unigram, bigram, and trigram patterns to clarify major transitions and their trends in the Chugoku district.

3. Overview of Data

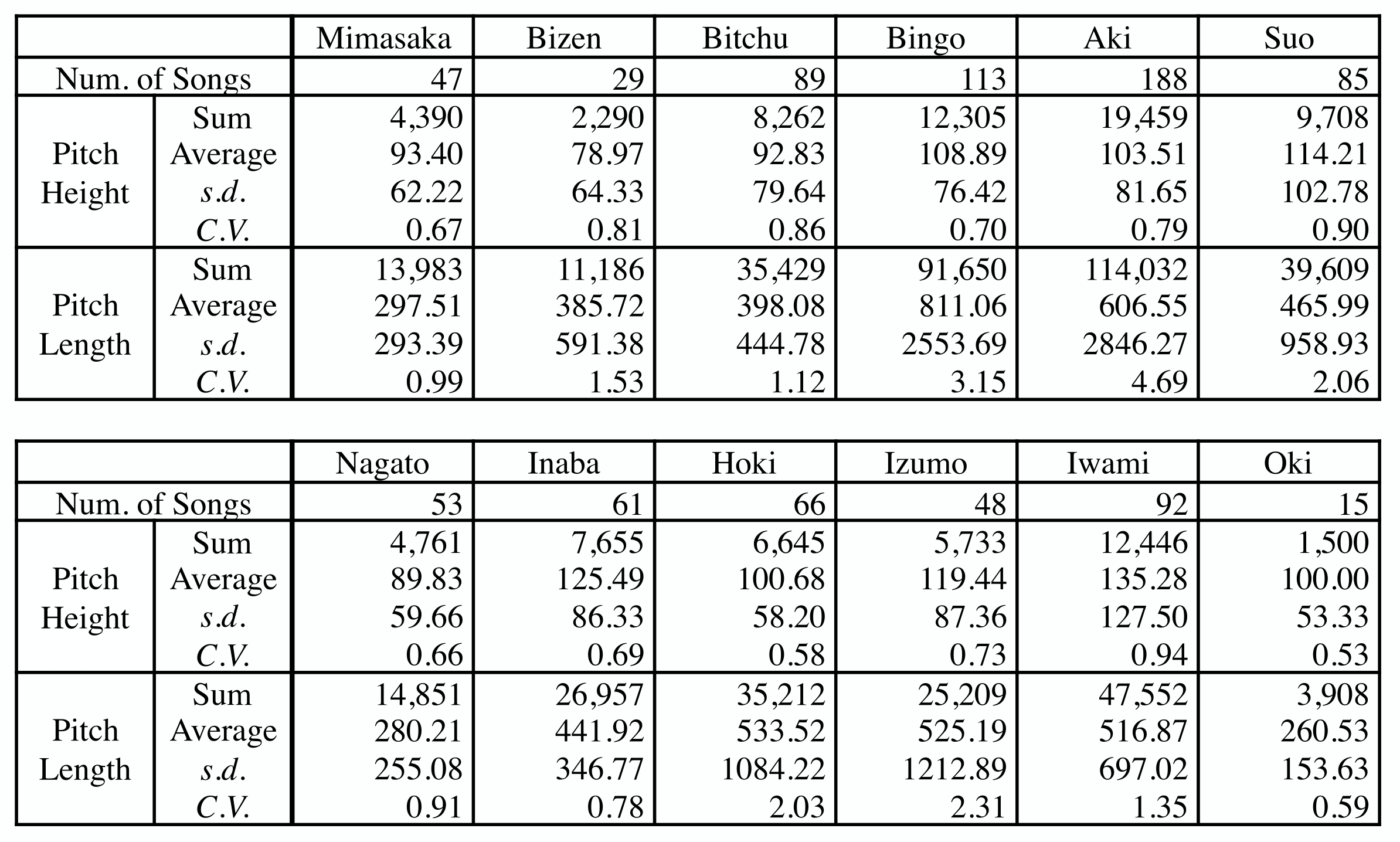

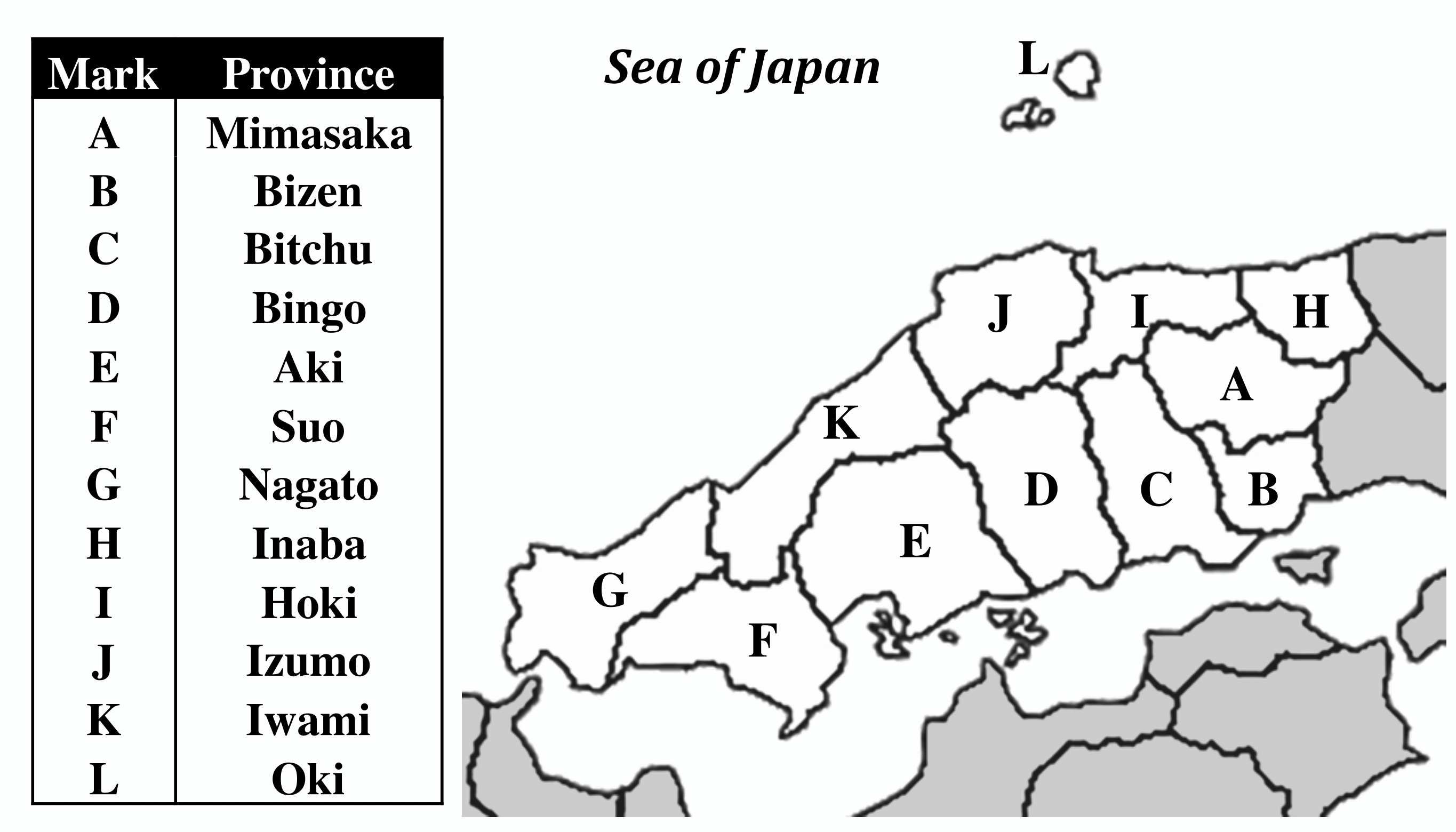

In order to quantitatively extract pitch transition patterns from Japanese folk songs, we sampled and digitized folk songs included in the Nihon Min’yo Taikan. We sampled all the songs in the music corpora included in the Chugoku Region volume (1966). Table 2 shows the statistics about the song pieces from each area in the Chugoku district. Figure 1 is a map of the provinces in the Chugoku district.

4. Results

4.1. Frequency of the First Transition

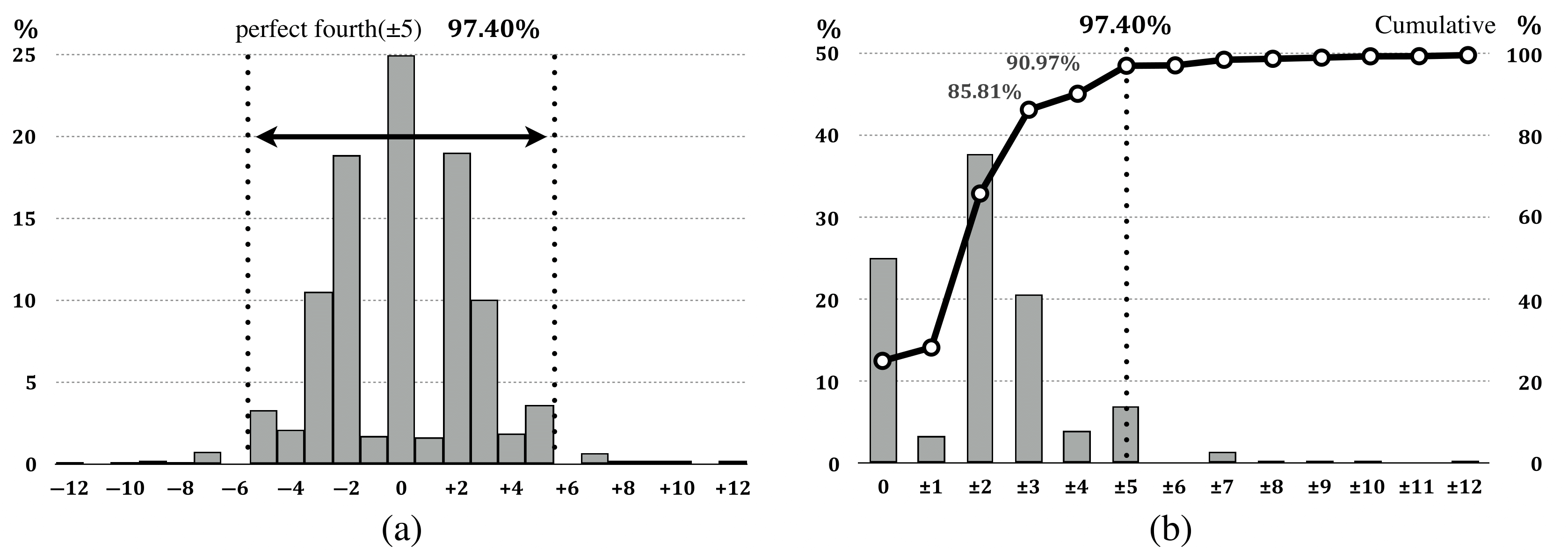

Figure 2(a) shows the usage frequency of the first transition patter (unigram). The graph implies that pitch transitions occur almost equally in both the ascending and descending directions. Figure 2(b) is a cumulative relative frequency diagram of the first transitions for ascending and descending order that confirms the trends for each interval. The profile shows that most of the voice range does not extend beyond the interval of perfect fifth (±7).

Based on studies of musical psychology, step-by-step changes in pitch height (in other words, pitch interval transitions that always involve ascending or descending order) are an indispensable factor by which humans perceive melodic patterns (Scruton 1997). Therefore, to extract the structures buried under repetition of notes, we will exclude the 0 intervals from sequence T in order to seek the pure changes of ups and downs within the melody.

4.2. Overall Summary of Bigram Patterns

Table 3(a) shows the top 40 bigram patterns. These components do not exceed the range of the perfect fifths (±7), and the values of the chains (intervals) also add up to a pitch interval between -5 and +5. In addition, we find that transition patterns that add up to 0 ( t i + t i +1 = 0), transition patterns that add up to ±5 ( t i + t i +1 = ±5, which is the interval of the perfect fourth), and patterns that include the interval of the perfect fourth in either component (e.g. patterns that form ( t i, t i +1) = (±5, *), (*, ±5)) also appear with high frequency.

4.3. Overall Summary of Trigram Patterns

Table 3(b) shows the top 40 trigram patterns. These components do not exceed the range of perfect fourths (±5), and the feature that stands out is that some of the top-ranked patterns are patterns with a single pitch transition attached to bigram. Most of the transition patterns fall in the range of the intervals of perfect fifths (±7). Furthermore, there are many high-ranked patterns in which the beginning two transitions or the last two transitions add up to form either the same degree of pitch ( t i + t i +1 = 0 or t i +1 + t i +2 = 0) or a perfect fourth pitch ( t i + t i +1 = ±5 or t i +1 + t i +2 = ±5).

5. Discussion

5.1. Koizumi’s Tetrachord Theory

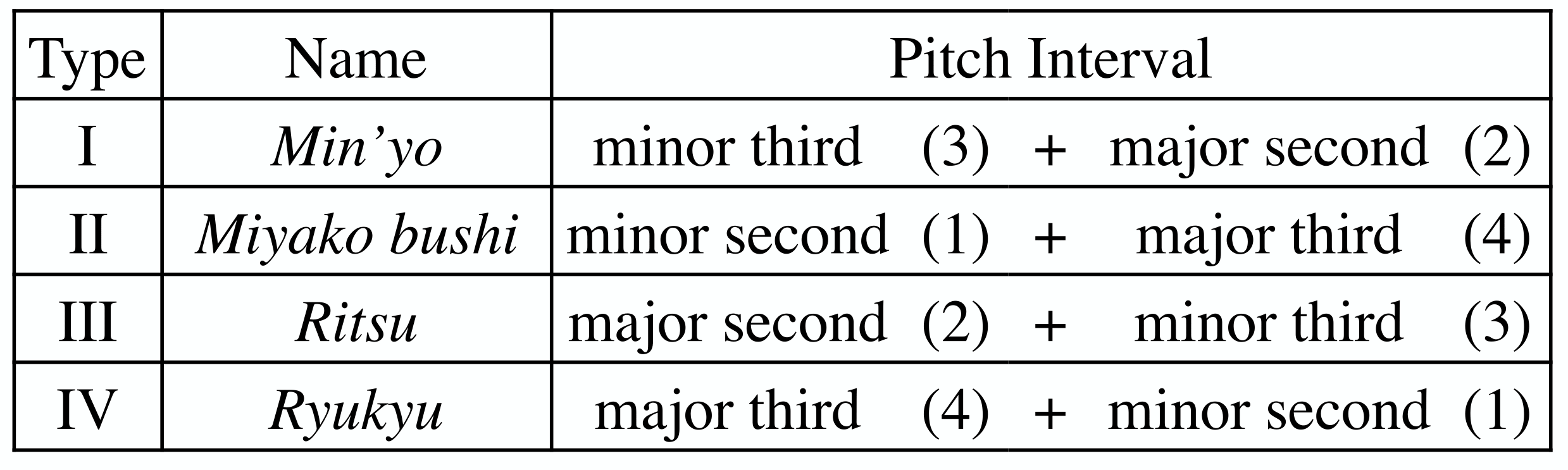

To speed things along, we will mention Koizumi’s tetrachord theory (1958). The tetrachord is a unit consisting of two stable outlining tones (nuclear tones) with the interval of a perfect fourth pitch, and one unstable intermediate tone located between them. Depending on the position of the intermediate tone, four different types of tetrachords can be formed (Table 4).

Using a bigram model representing pitch transitions, all four types of tetrachords can be expressed as follows in ascending order: min’yo (+3, +2), miyako bushi (+1, +4), ritsu (+2, +3), and ryukyu (+4, +1). Depending on the positions of the three initial pitches in a tetrachord, six transition patterns can be considered in perceiving a tetrachord in two steps (bigram). Therefore, the amount of tetrachords within two steps can be obtained by counting the pairs of 24 transition patterns in sequence T.

5.2. Province Similarities Based on the Frequency of Occurrence of Tetrachords

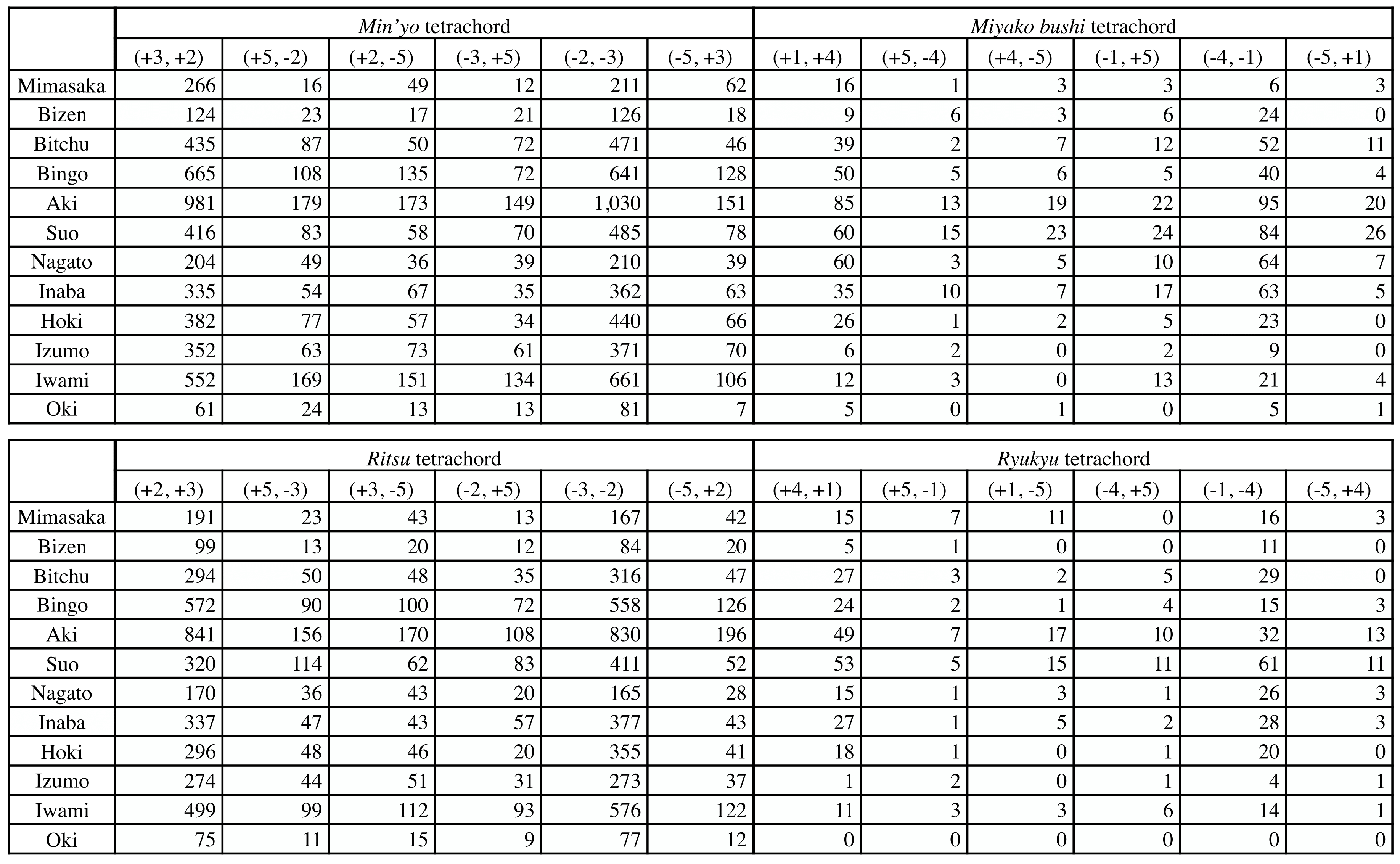

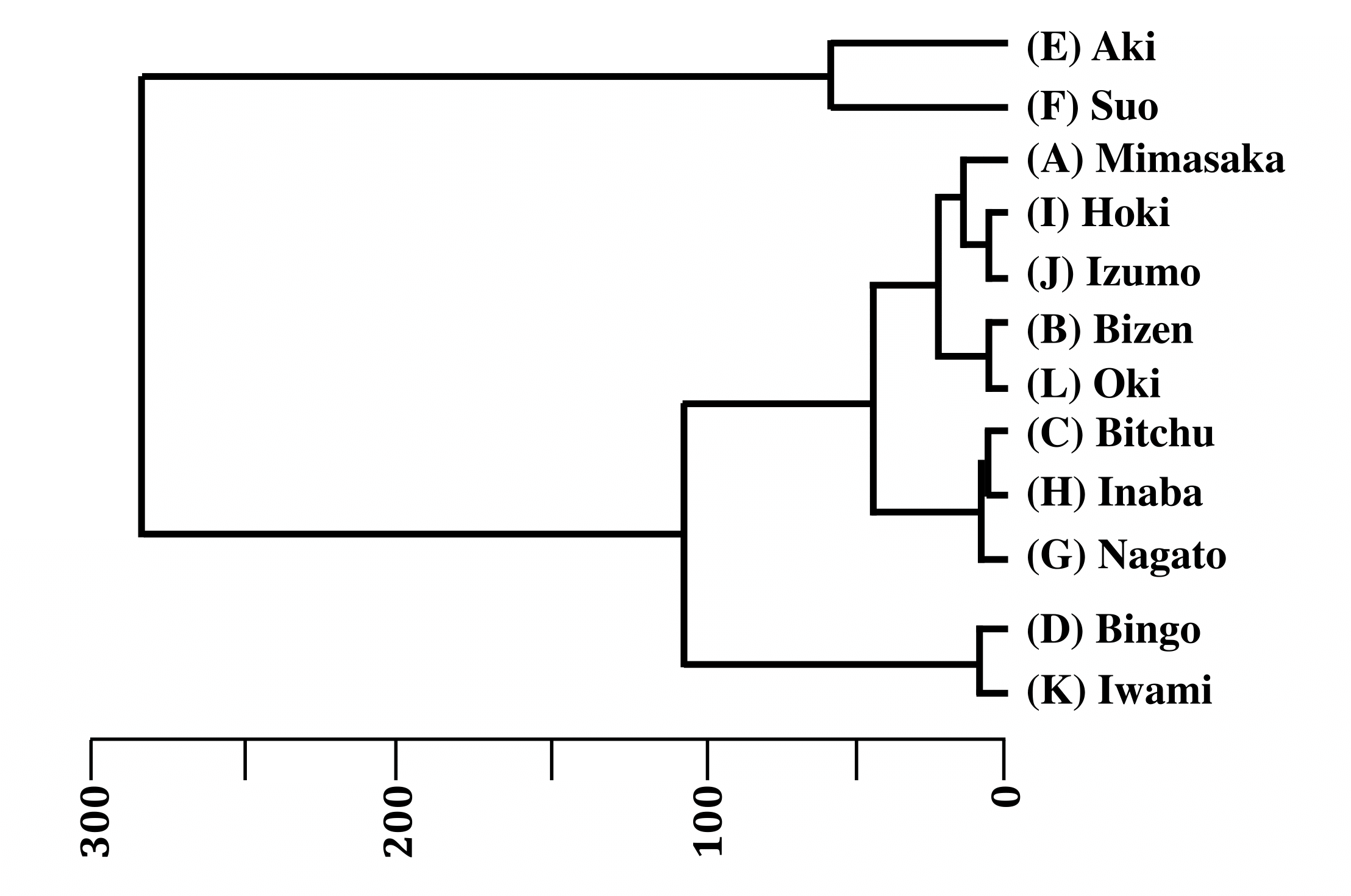

Table 5 shows the frequency that the 24 transition patterns for the four tetrachords appear for all 12 provinces. Here, we did hierarchical cluster analysis on the 24 transition patterns for each province to objectively demonstrate similarities in the 12 provinces. The dendrogram in Figure 3 shows hierarchical cluster analysis results. When calculating distances between each element, we normalized the frequency that the tetrachords appear, and used the Euclidean distance and the algorithm from the Ward method.

If we look for h = 60 (a height where there are three vertical lines) and trace them to the individuals, this partition of three clusters separates the 12 provinces into C 1 = {Aki, Suo}, C 2 = {Mimasaka, Bizen, Bitchu, Nagato, Inaba, Hoki, Izumo, Oki}, and C 3 = {Iwami, Bingo}, which almost classifies the Chugoku district into geographically close groups. Meanwhile, it also stands out that only Nagato is separately geographically isolated.

5.3. Sea Route Connecting the Provinces

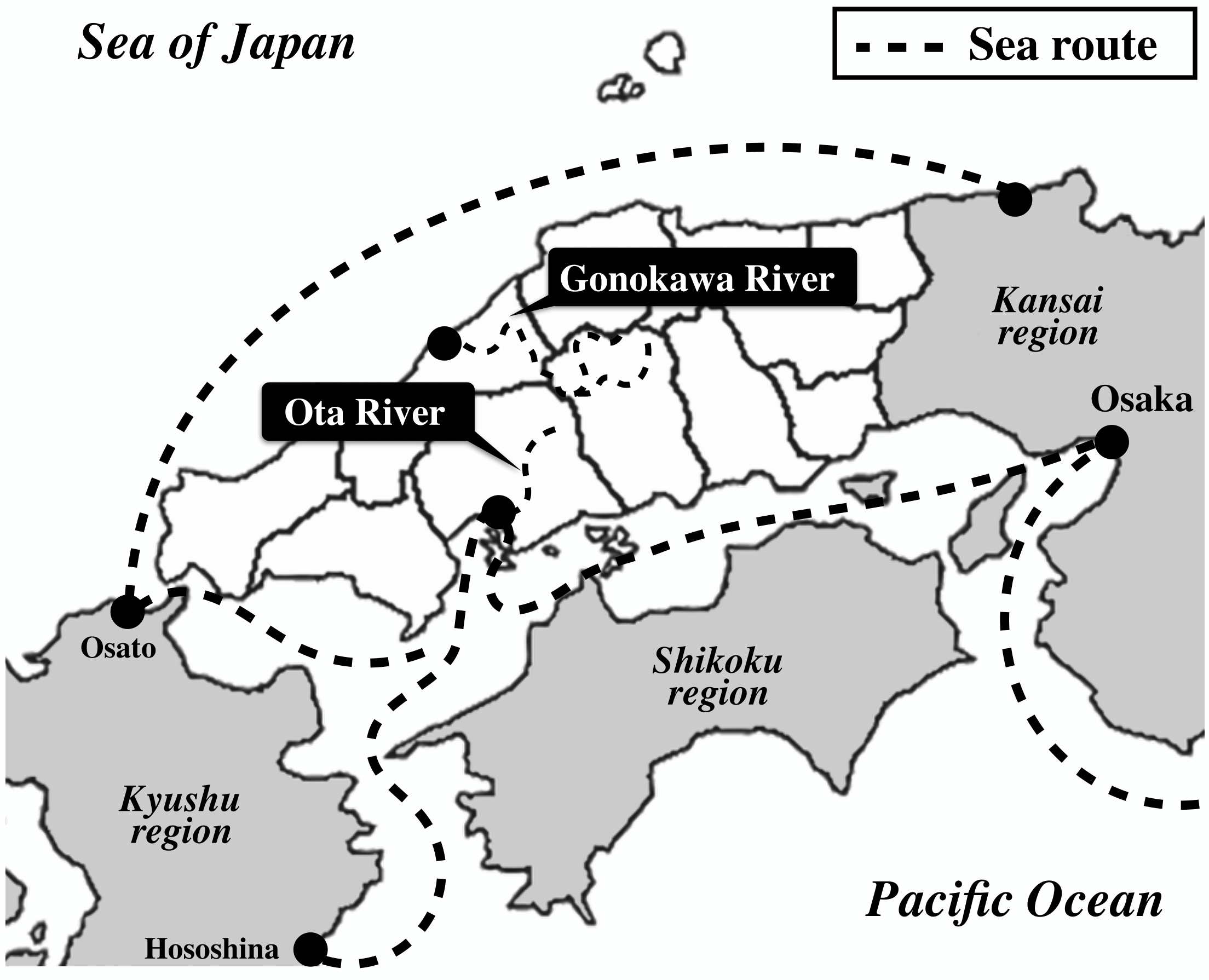

The cluster analysis results did not turn out to match the famous two ancient divisions based on the main road: San’yo = {Mimasaka, Bizen, Bitchu, Bingo, Aki, Suo, Nagato} and San’in = {Inaba, Hoki, Izumo, Iwami, Oki}. However, instead it is possible to consider each cluster based on sea routes (Figure 4).

Since ancient times, the Chugoku district has been an area travelers passed through when traveling from the Kansai district (a center of regional culture in Japan) to get to Kyushu region, which had close relations with China and Korea. Since there wasn’t much flat land and there are many mountain ranges, sea routes played an important role in transportation.

The existence of the Ota River, a major river and also a sociocultural and economical foundation in the Chugoku district, supports the grouping of the two provinces in C 1. From an oceanic commerce point of view, the north and south sea routes that link the Nagato and Kansai regions also support the grouping of providences in C 2. It is also possible to say that the Gonokawa River, which functioned as a traffic relay point between San’yo and San’in, supports the grouping of provinces in C 3. In this way, we find that rivers have important functions that exert musical influence as well as indicate boundaries between districts and geographical areas.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we digitized the melodies of traditional Japanese folk songs in the Chugoku district, and quantitatively analyzed its pitch transition patterns using n-gram modeling, and did a classification experiment based on the frequency of occurrence of the tetrachords to see the differences in each province. As a result, we constructed the possibility that the melodic features in the Chugoku district spread by land and sea routes based on actual music data analysis. However, we should be able to describe the relationships influencing musical culture between regions in detail if we develop this analysis on a nationwide scale. In further research, it is possible to clarify the structural commonalities and differences between areas by conducting analysis on musical corpora nationwide including folk song pieces from neighboring regions such as the Kyushu, Shikoku, and Kansai regions, which has not really been pursued in existing humanities research fields. We believe this will empirically clarify the musical culture phenomena by which music spreads and changes.

- Kawase, A. and Tokosumi, A. (2011). Regional classification traditional Japanese folk songs, International Journal of Affective Engineering, 10(1): 19-27.

- Koizumi, F. (1958). Studies on Traditional Music of Japan 1, Ongaku no tomosha.

- MusicXML. http://www.musicxml.com/for-developers/ (accessed 16 February 2016).

- Nihon Hoso Kyokai (1944-1993). Nihon Min’yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs).

- Scruton, R. (1997). The Aesthetics of Music, Oxford University Press.