Authors: Asanobu Kitamoto, Yoko Nishimura

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: semantic web, digital criticism, evidence-based approach, historical studies, digital research infrastructure

Digital Criticism Platform for Evidence-based Digital Humanities with Applications to Historical Studies of Silk Road

1. Introduction

Source criticism is a scholarly process fundamental to many disciplines of humanities, especially in historical studies. However, it is mainly designed for a traditional way of research, namely human scholars read a textual source without producing structured evidences for reuse. Our proposal is to extend the traditional methodology of source criticism to digital research infrastructure on which scholars records the reasoning process from evidences to facts, and share them with other scholars so that the detail of the reasoning process can be transparently reproduced. Our approach, digital criticism, aims at realizing this idea on digital criticism platform (DCP) toward evidence-based digital humanities with the support of Semantic Web technology.

An evidence-based approach is also used in quantitative humanities, but digital criticism is a fundamentally different approach. Digital criticism focuses on reading sources in a critical manner, while quantitative humanities focuses on deriving numerical values from the collection of sources. Generally speaking, quantitative humanities tries to make abstraction of corpus through quantitative aggregation, while digital criticism tries to make critique of sources through digital analysis with support for the management of a layered abstraction process.

2. Core concepts of digital criticism

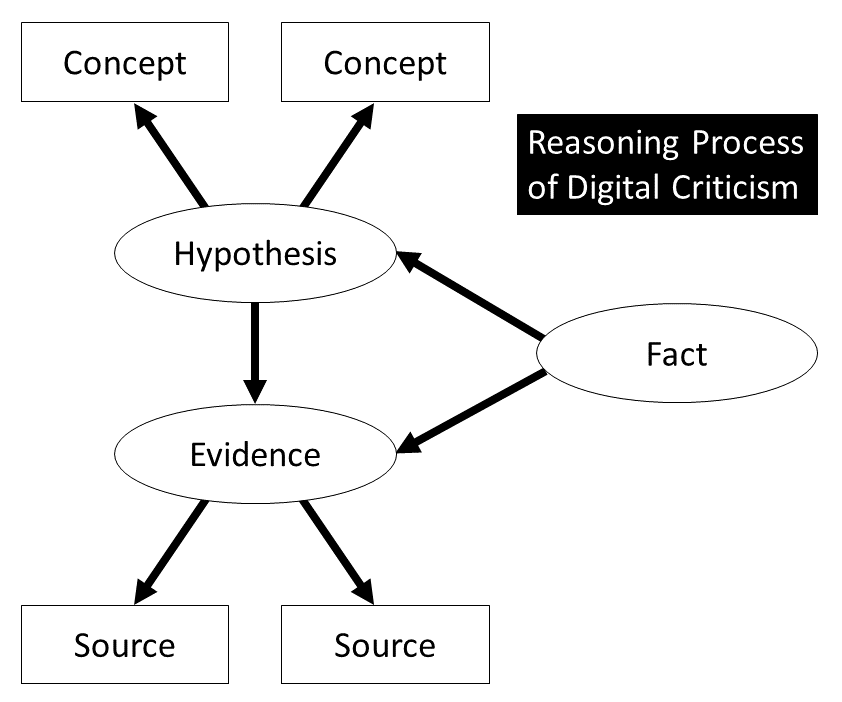

The main contribution of the paper is evidence network on which digital criticism is performed. The network consists of four concepts, namely evidence, hypothesis, fact, and reliability. Those concepts have our own definition to organize the historical reasoning process into an explicit model.

- Evidence is relationship between sources. If a photograph A takes the same scene with a photograph B, they are linked as an evidence with reproducible parameters of how photographs can be matched.

- Hypothesis is relationship between historical concepts. If a ruin A and ruin B have different names but are believed to be the same ruins, they are linked as a hypothesis with supporting evidences and other descriptions on the reasoning process.

- Fact is relationship between evidences and hypotheses to claim reusable knowledge for future research.

- Reliability is an attribute of evidences and hypotheses to represent the degree of reliability estimated by the scholar on registration. Because the estimated reliability may be different for each scholar, evidences and hypotheses should always be linked to a user entity who made the action.

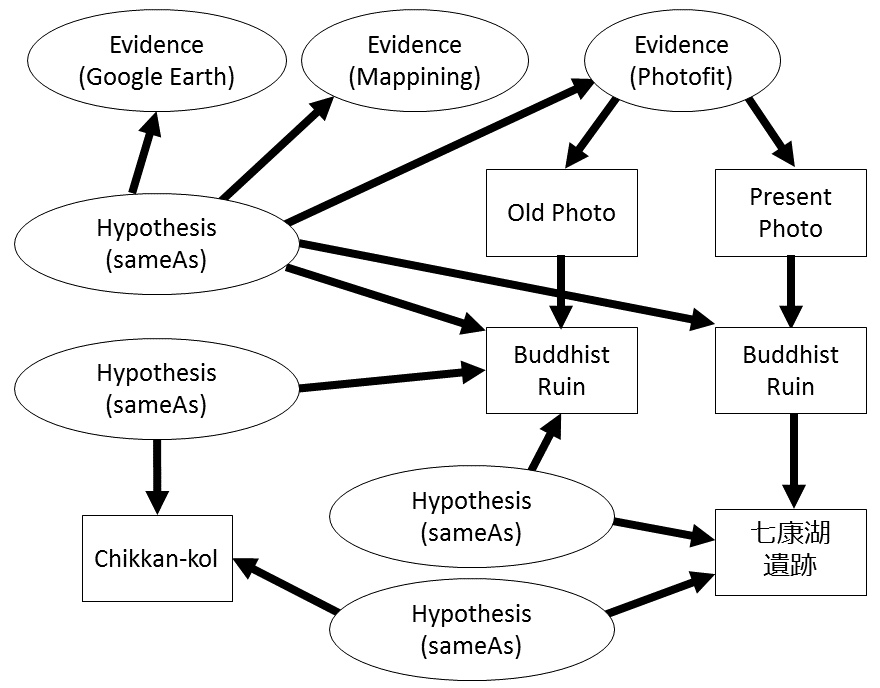

Figure 1 illustrates a schematic diagram of evidence network. A scholar can build up the network starting from each evidence and hypothesis. Another scholar who wants to reuse the knowledge can start from the fact, and track back to hypotheses and evidences to check the reliability of the reasoning process.

3. Digital Criticism Platform (DCP)

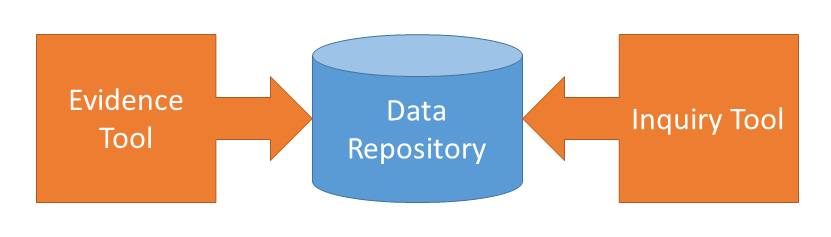

Evidence network is a directed graph with semantic annotation, and the graph structure is built using RDF (Resource Description Framework). Hence a search over a graph can be implemented using SPARQL, which is a query language for a RDF graph. To construct and study the evidence network, we develop Digital Criticism Platform (DCP) with three components, namely data repository, evidence tool, and inquiry tool as illustrated in Figure 2.

- Data repository archives digital resources with unique IDs and metadata. We developed data repository using DSpace as infrastructure for its reliability and extensibility to Semantic Web environment.

- Evidence tool works on various types of media for collecting evidences. We developed three tools, Mappining, Photofit, and MemoryHunt, for maps, photographs, and field work, respectively.

- Inquiry tool is to study and sophisticate the evidence network using Semantic Web technology such as SPARQL. This component is now under study, and has not reached the development phase.

In the following, we focus on three evidence tools to describe more detail of the tools. Those tools should be integrated into data repository so that every evidence is registered as a part of evidence network. Three tools are already in operation, but only Photofit is fully integrated into data repository at the time of writing.

4. Mappining

Mappining (Kitamoto 2012) is a web-based tool for matching maps (Figure 3). This tool employs an idea of “interactive georeferencing” in contrast to geometric correction. Interactive georeferencing uses a pin to match two maps at a single point, in a similar way of pinning cloths. When we put a pin, two maps scroll together, while when we release a pin, only one map scrolls. Using this interface, any point on a map can be matched with another map for overlay-based comparison. Interactive georeferencing is advantageous for reading sources because geometric distortion is not introduced. A pin is an evidence to claim that each point on a map represent the same location on earth.

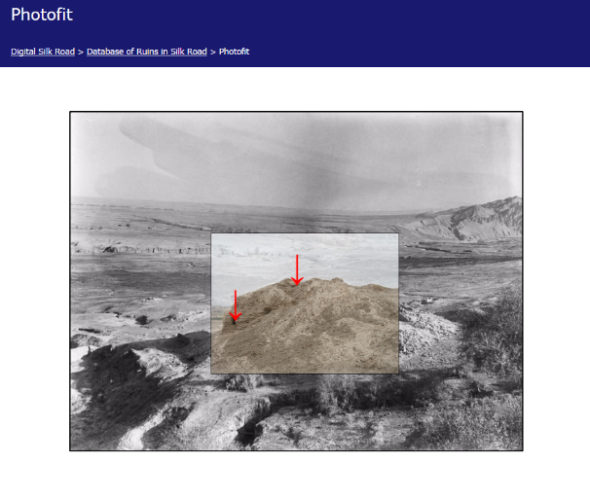

5. Photofit

Photofit is a web-based tool for matching photographs (Figure 4). The target of the tool is two photographs taken from similar locations but different angles at different time. It allows planar shift and zooming transformation for two photographs to find the best match. On success, it is an evidence to claim that two photographs take the same scene or the same object. This evidence may lead to a new hypothesis on the identity of historical concepts when the captions of two photographs represent different historical concepts.

6. MemoryHunt

MemoryHunt (Kitamoto 2015) is a mobile app for matching a photograph with the real world (Figure 5). It shows a target photograph on the viewfinder of a smartphone camera with controllable transparency, and the task of a user is to find the same location and the same direction that the photograph was taken. On success, a mobile app can record the location and direction as metadata of the photograph. This may lead to an evidence between an object appearing in the photograph and one in the present world.

7. Evidence network

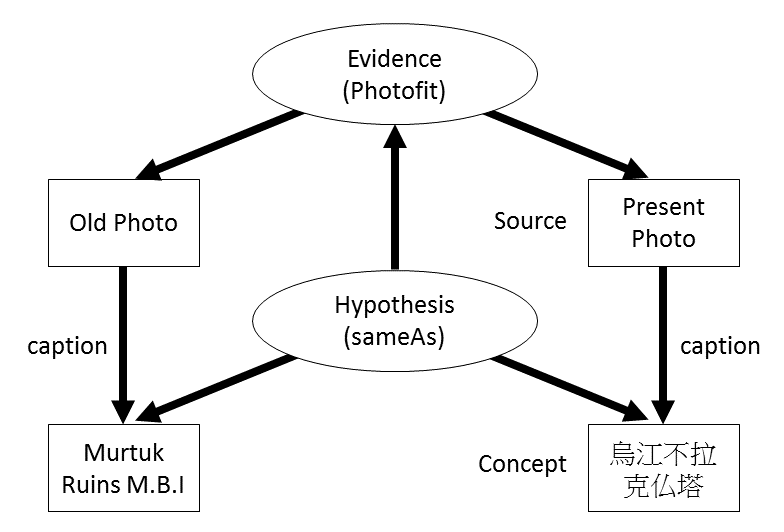

The purpose of digital criticism is to build an evidence network in which historical sources are linked through evidence nodes, and historical concepts are linked through hypothesis nodes to derive fact nodes supported by evidence and hypothesis nodes. We start by a bottom-up process of registering evidences and hypotheses which are still fragmented. We then switch to a top-down process of viewing a graph structure as a whole to discover unknown relationships. In the following, we use our past results on Silk Road ruins as case studies to check the validity of our approach. Due to the incompleteness of DCP, the following diagrams were manually drawn.

Figure 5 shows a simple evidence network. A photograph in a book is matched with another photograph in another book using Photofit, and an evidence node is added with transformation parameters. We also know that, through captions, each photograph represents a ruin known by different names. We then add a hypothesis node based on the above evidence to claim that two ruins known by different names are the same.

Figure 6 shows a complex evidence network. Multiple tools are used for matching multiple sources, such as Mappinning, Photofit, and Google Earth. The evidence network suggests relationship among a Buddhist ruin and a ruin known by the name Chikkan-kol and another ruin known by “七康湖遺跡. ” This relationship was our discovery previously reported in a paper (Nishimura and Kitamoto 2010), but digital publishing in the form of evidence network offers clearer representation of a compex reasoning process.

8. Conclusion

We proposed digital criticism platform (DCP) as a model of source criticism on a digital platform. Digital criticism tries to simulate the traditional method of source criticism and extend it to take advantage of digital research infrastructure. Digital Criticism is the upgraded version of our past proposal on “data criticism” (Kitamoto and Nishimura 2014), after shifting research focus on the type of sources to the way of digital scholarship. The methodology of criticism is also investigated in different approaches, such as algorithmic criticism (Ramsay 2011).

Knowledge representation of historical evidences has a large number of related literature. In particular, Pasin proposed the usage of factoid model for accumulating evidences for prosopography in the linked data world (Pasin and Bradley 2013), and linked data is also used for places such as Pelagios (Isaken et al. 2014). We also use the same concept of linking entities and uses sources as evidences, but digital criticism focuses more on accumulating structured evidences and hypothetical links. Another important work for the refinement of evidence network is knowledge representation for argumentation, such as CRMinf argumentation model, an extension of CIDOC-CRM (Paveprime Ltd and collaborators 2015). Finally, we are yet to make choices on metadata standards or vocabularies, which are open questions.

The long-term goal is to design a digital publishing platform for evidence citation. Historical facts can be tracked to evidences to clarify the reliability of evidences that support historical facts. This leads to increased transparency of research, and to realize better data management planning.

9. Acknowledgments

This work is supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26540178. Software codes for DCP was developed by Mr. Tomohiro Ikezaki.

- Isaken, L., Simon, R., Barker, E. T. E. and Cañamares, P. S. (2014). Pelagios and the emerging graph of ancient world data. Proceedings of the 2014 ACM conference on Web science, pp. 197-201.

- Kitamoto, A. (2012). Mappining. http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/digital-maps/mappinning/ (accessed 6 March 2016).

- Kitamoto, A. and Nishimura, Y. (2014). Data Criticism: General Framework for the Quantitative Interpretation of Non-Textual Sources. Digital Humanities 2014: Conference Abstracts.

- Kitamoto, A. (2015). MemoryHunt: A Mobile App with an Active Viewfinder for Crowdsourced Annotation through the Re-experience of the Photographer. Fifth Annual Conference of the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities (JADH2015).

- Nishimura, Y. and Kitamoto, A. (2010). Identification of Ruins Excavated by Silk Road Expeditions through Matching Names and Locations by Stein Maps and Google Earth. IPSJ SIG Computers and the Humanities Symposium 2010, pp. 255-62. (in Japanese).

- Pasin, M. and Bradley, J. (2013). Factoid-based prosopography and computer ontologies: towards an integrated approach. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30(1): 86-97.

- Paveprime Ltd and collaborators. (2015). CRMinf: the Argumentation Model, An Extension of CIDOC-CRM to support argumentation.

- Ramsay, S. (2011). Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism. University of Illinois Press.