Authors: Marius Hug, Christian Thomas

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: collaborative research, digital scholarly edition, history of sciences and humanities, DH-tools, TEI-XML

The »Hidden Kosmos« of scientific instruments in Alexander von Humboldt's »Vorlesungen über physikalische Geographie« – or: What on earth is an »Ariometer«?

1. Abstract

In 1827/28 Alexander von Humboldt presented the scientific knowledge of his time in lectures which became famous in their own right as a milestone in the popularization of science as well as due to their apparent connection to Humboldt’s most important work “Kosmos. Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung” (1845–62).

The project “Hidden Kosmos—Reconstructing Alexander von Humboldt’s ‘Kosmos-Lectures’” 1 is located at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Within two years (ending in August, 2016) the project digitizes and virtually brings together eleven attendee’s lecture notes (all that are known at the moment) of the “Vorlesungen über physikalische Geographie”, the so-called “Kosmos-Lectures”, coming from libraries, archives as well as private collections in Germany, Poland (Kraków) and Turkey.

The TEI-encoded transcripts of about 3500 manuscript pages will be published as a standard-compliant, deeply annotated and highly integrated corpus under CC by-sa. 2

While the project’s goal is to enable an intensive exploration of Humboldt’s lectures, our poster will abstract a little from the impressive range of topics of Humboldt’s lectures and focus on technical solutions applied in the project to make the corpus likewise fruitful to Humboldt researchers, the general public and Dhists.

2. Starter

On March 13, 1828 Alexander von Humboldt gave his 14th talk of the Kosmos-Lectures at Berlin’s Singakademie. 3 At the end of his talk he told his audience:

... für den technischen Gebrauch hat man von diesen neueren Entdeckungen eine Anwendung gemacht, durch die Einrichtung eines Ariometers, od. Wollmessers. Ein Lichtstrahl welcher bei einem feinen Faden Wolle vorbei geht, erleidet eine Beugung u. bildet farbige Frangen oder Ringe, die um so breiter erscheinen als der Faden zarter od. dünner ist. 4

The topic of this lecture is fairly clear: Optical interference and the diffraction of light. The main instrument mentioned is an “Ariometer” for measuring the thickness of woolen threads. This at least is the conclusion from what the anonymous writer of this text tells us.

3. Formal setting

The project’s tag set strictly follows the DTABf-M (cf. Haaf/Thomas, 2015) 5 which is a specific DTA “Base Format” (DTABf) for manuscripts. This strict subset of the TEI P5 tag set provides “a balance between expressiveness and precision as well as an interoperable annotation scheme for a large variety of text types in historical corpora [...].” (Cf. Haaf et al., 2014)

The tag set and corresponding RNG-schema are the basis for a homogeneous TEI-encoding of all documents by different encoders, i. e. typists from the (external) vendor—providing transcription and TEI-conformant annotation of the easier legible manuscripts—as well as our project team.

The linguistic analysis of texts at the DTA (incl. lemmatization and fully automatized normalization of historical forms) and their search engine enable an ideal exploitation of the attendee’s lecture notes in the context of the DTA corpora, where hundreds of other texts from Humboldt himself as well as his contemporaries, predecessors and successors can be accessed and linked to the Kosmos-Lectures.

Obviously, as we are dealing with different notes by several attendees of Humboldt’s lectures—i. e. still referring to the same oral presentation—a collation of the witnesses is one essential way of access. The similarities and differences between the witnesses call for collation tools. CollateX or juXta, for instance, are well known and established DH tools for completely automatized detections and visualizations of comparisons of two or more texts. They are of great value for our project (cf. Thomas, 2014/15) and we will illustrate this by making accessible collation sets during our poster demo.

Due to our TEI-encoding more options for evaluations are given:

- Humboldt’s course is segmented chronologically into single lectures. 6 This is thoroughly done via <div type="session" n="[count]">. This approach enhances the possibilities of accessing parallel reading of the transcripts.

- A systematic access to the sources is enabled due to referencing persons within the TEI documents (<persName ref="[ID]">) as a basis for an encompassing index of all postscripts linked to authority records.

- A third way of accessing the Kosmos-Lectures will be a complete bibliography of all mentioned sources tagged with <bibl>.

4. Contentwise Resumption

Starting point was the “Ariometer” and the diffraction of light in the one manuscript quoted above. A use case would be to see what the other listeners noted. For example, one other attendee wrote:

… durch die Beugung der Lichtstralen, indem sie durch einen engen Raum gehn, entstehn farbige Franzen, die man am besten erhalten kann, wenn man einen Lichtstral durch das Fenster bei einem dünnen Faden vorbei in ein dunkles Zimmer auf eine helle Wand leitet… 7

Similarities between the two texts are obvious: light beams, diffraction, a woolen thread and coloured stripes of light. But while the first extract gives the impression of Humboldt being interested in measuring woolen threads, these clearly function as instruments for illustrating a physical phenomenon in the later passage.

The natural attempt to search for “Ariometer” in our corpus gives no results. 8 We can derive from the context given in the quote above that Humboldt is talking about physical phenomena, but it would be helpful to have a protagonist. So let's refine our search: 9

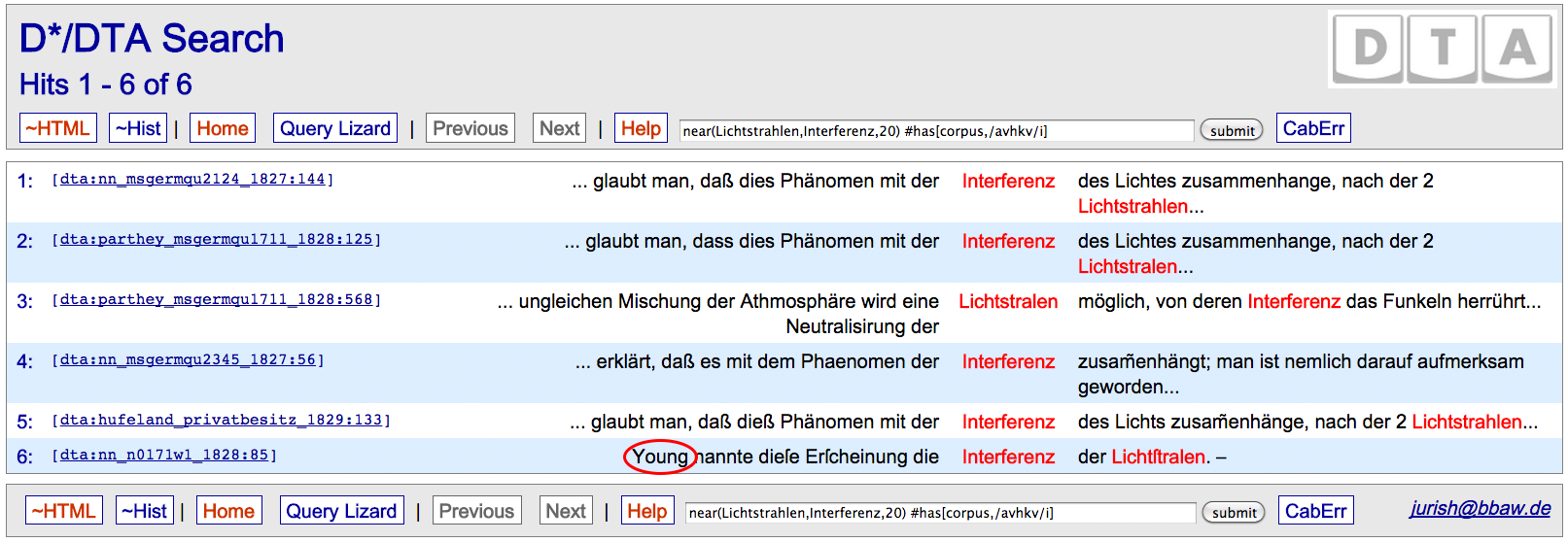

near(Lichtstrahlen,Interferenz,20) #has[corpus,/avhkv/i]

Looking at the results (see fig. 1) leads us to Thomas Young as well as Jung 10, which obviously only is a German version of the first. Next attempt:

near(*meter,/[JY]o?ung$/,20) #has[corpus,/avhkv/i]

And this leads to another meter, the “Circometer”. Maybe we couldn’t find the “Ariometer” since it doesn’t exist? To shorten the track here: A “Circometer” doesn’t exist either. What we are in fact looking for is the so-called eriometer.

What we are facing here is an inherent difficulty of our text type: attendee’s lecture notes. It’s always possible that the listeners misheard something. This is why 1) the deeply granulated TEI encoding of the project, 2) the technical solutions provided by the DTA and 3) text-comparison visualizations (being developed for our project’s) are absolutely necessary.

5. Summary

The following DDC-search leads to the third volume of the Kosmos (1850), where Humboldt is talking about the above mentioned physical phenomena:

near("$p=ADJA /Fran[szg]en/",/(Wolle|Interferenz)/,20) #has[corpus,/(avhkv|kosmos)/i]

About 30 years after his lectures the eriometer and the wool are no issue any more. The reason for this is not inherent, but a little research on the basis of other digitized sources reveals it: Whereas the real eriometer—the apparatus for measuring the fineness of woolen threads—, which Young used to demonstrate the diffraction of light in his famous Lectures on Natural Philosophy at the Royal Institution, became forgotten, 11 the idea of combining the craft and the theory (or the engineer and the scientist) succeeded:

… das ähnliche Instrument dient dazu die Güte der Wolle zu messen, und die Natur der Weltkörper zu bestimmen. 12

Apart from the implementation of means for collation it is obvious that linking to more (external) data-sets, as shown here, will add even further value to the project. 13

- N. N. (1828). Physikalische Geographie. Vorgetragen von Alexander von Humboldt. In Deutsches Textarchiv, Berlin. http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/nn_msgermqu2124_1827/(accessed 12 February 2016).

- Erdmann, D. and Thomas, C. (2014). … zu den wunderlichsten Schlangen der Gelehrsamkeit zusammengegliedert. Neue Materialien zu den ,Kosmos-Vorträgen‘ Alexander von Humboldts, nebst Vorüberlegungen zu deren digitaler Edition. HiN – Humboldt im Netz. Internationale Zeitschrift für Humboldt-Studien, 15(28): 34–45, http://hin-online.de/hin28/erdmann-thomas.htm/ (accessed 12 February 2016).

- George, S. and Guarino, M. (1973). Young’s Eriometer: History and Modern Teaching Use. Physics Education, 8(6): 392–96.

- Haaf, S., Geyken, A. and Wiegand, F. (2014/15). The DTA "Base Format": A TEI Subset for the Compilation of a Large Reference Corpus of Printed Text from Multiple Sources. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative (jTEI), 8, http://jtei.revues.org/1114/ (accessed 12 February 2016).

- Haaf, S. and Thomas, C. (2015). DTABf-M: A TEI-conformant Base Format for Manuscripts. Presentation at the TEI Converence and Members Meeting 2015, Lyon. http://tei2015.huma-num.fr/en/papers/#108 (accessed 12 February 2016).

- Humboldt, A. V. (1845–62). Kosmos. Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung. 5 Bände. Stuttgart (u.a.): Cotta.

- Juxta Collation Software, For Scholars, http://www.juxtasoftware.org/.

- Parthey, G. (1828/28). Alexander von Humboldt[:] Vorlesungen über physikalische Geographie. Novmbr. 1827 bis April,[!] 1828. Nachgeschrieben von G. Partheÿ. Berlin, In Deutsches Textarchiv, http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/parthey_msgermqu1711_1828/ (accessed 12 February 2016).

- textloop Martina Gödel, http://textloop.de/.

- Thomas, C. (2015). Hidden Kosmos – Humboldts ‚Kosmos-Vorträge‘ als Probe der Digital Humanities. Vortrag auf der DHd-Jahrestagung 2015 „Von Daten zu Erkenntnissen: Digitale Geisteswissenschaften als Mittler zwischen Information und Interpretation“, 23.–27.2.2015, Zentrum für Informationsmodellierung – Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities an der Universität Graz. Book of Abstracts, http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:dhd2015.abstracts-vortraege: [193]ff.

- Young, T. (1807). A Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts. Johnson.