Authors: Hannah Kermes, Stefania Degaetano-Ortlieb, Ashraf Khamis, Jörg Knappen, Elke Teich

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: digitization, resource creation, discovery

The Royal Society Corpus: Towards a high-quality corpus for studying diachronic variation in scientific writing

Big data are a potential source for quantitative research in the humanities, but typically they do not contain all relevant contextual meta-data (time, register/genre, social group, author, etc.) to be readily usable for social, historical or philological studies (cf. Schöch, 2013). Small corpora, in contrast, are typically carefully hand-crafted and provide rich meta-data as well as structural and linguistic data, but the application of data-driven analysis techniques is impeded by their small size.

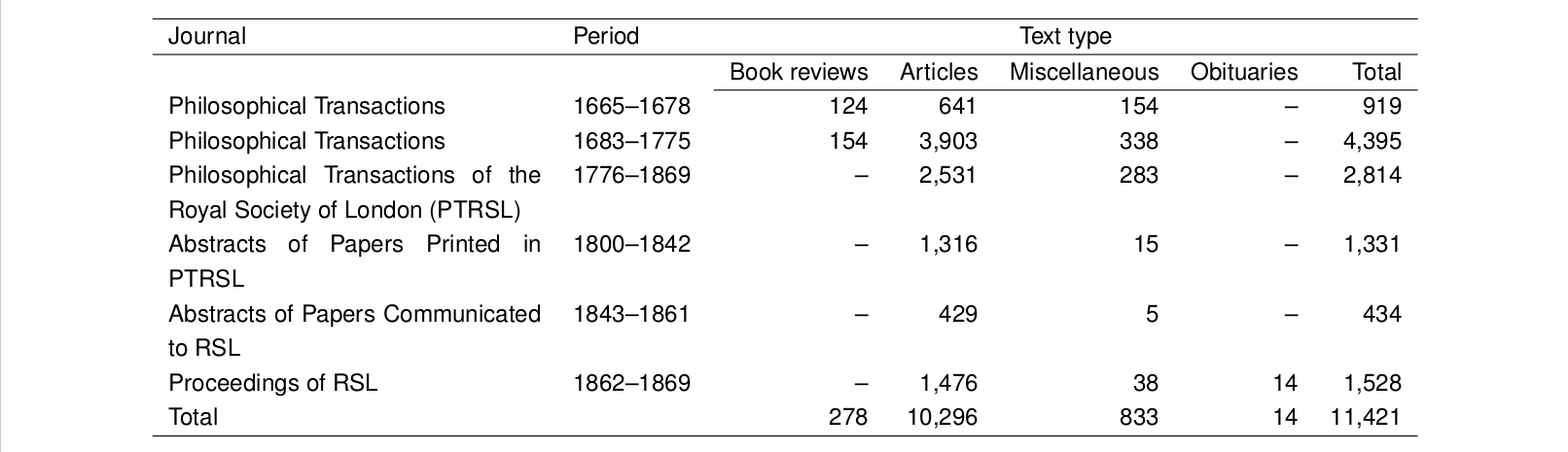

We introduce a diachronic corpus of English scientific writing - the Royal Society Corpus (RSC) - adopting a middle ground between big and ‘poor’ and small and ‘rich’ data. The corpus has been built from an electronic version of the Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of London and comprises c. 35 million tokens from the period 1665- 1869 (see Table 1). The motivation for building a corpus from this material is to investigate the diachronic development of written scientific English.

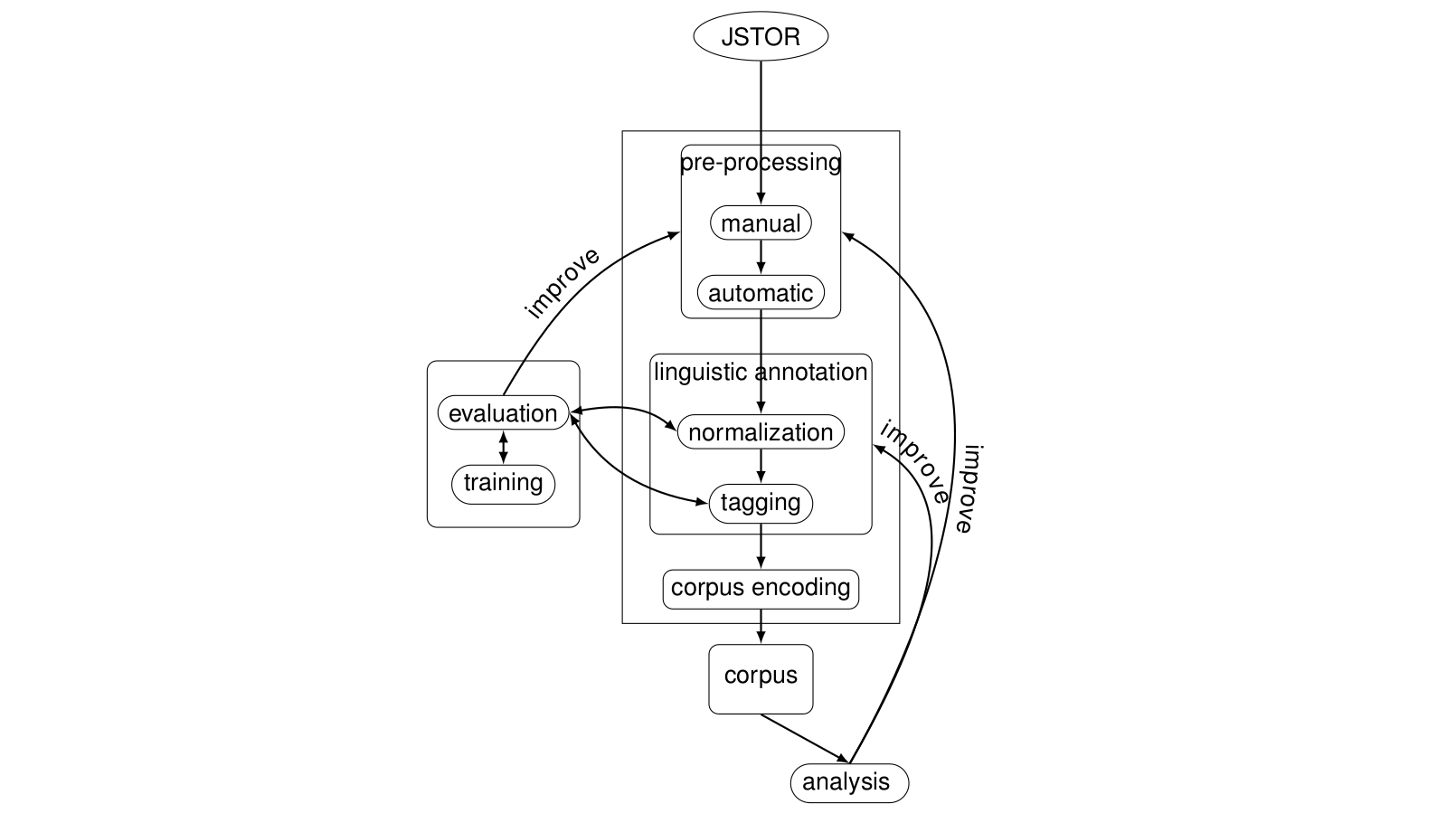

In terms of corpus building (see Figure 1 for a schematic overview), the sources for the RSC were obtained from JSTOR and include some but not all relevant meta-data (year of publication and authors, but not disciplines), structural data is partial and erroneous (e.g. scrambled pages, text duplicates), and the base text contains OCR errors. To move towards a cleaner and richer version of the corpus, an approach is needed that allows obtaining good-quality base-text data and relevant meta-data as well as structural and linguistic data with affordable effort. For this purpose, we use a combination of pattern-based techniques (e.g. by adapting the patterns for OCR corrections made available by Underwood and Auvil) 1 and data-mining methods (e.g. topic modelling (Blei et al., 2003)to approximate disciplines; cf. McFarland et al. (2013)for an overview of types of topic models applied to capture differentiation in scientific language). Additionally, to enrich the RSC with basic linguistic annotations, we build on existing tools adapting them to the diachronic material. For normalization we use VARD (Baron and Rayson, 2008)with a model we trained on a manually normalized subset of the RSC, and for tokenization, lemmatization, segmentation and part-of-speech annotation we useTreeTagger (Schmid, 1994)on the normalized texts. Inspired by the idea of Agile Software Development (Cockburn, 2001), we intertwine the actual corpus building with corpus annotation and analysis, continuously building new versions of the corpus whenever we see a recurrent problem in data quality. We work with a dedicated pipeline and keep the corpus-building process as modular and automatic as possible, applying manual work before the first automatic step. In the last step, the corpus is encoded in CQP format (cf. IMS Open Corpus Workbench (CWB) (Evert and Hardie, 2011)) and can be accessed via a CQPweb interface (Hardie, 2012) 2.

In terms of analysis, our main assumption is that due to specialization, scientific texts exhibit greater encoding density over time (Halliday and Martin, 1993),resulting in a specific discourse type characterized by high information density (Crocker et al., 2015) that is functional for expert communication (but rather inaccessible to lay persons). Linguistically, this may be reflected in lexical compression (e.g. compounding, derivation) and syntactic reduction (e.g. relativizer omission, contractions). For instance, there is evidence from the Thesaurus of the OED (Oxford English Dictionary) 3 that affixation rises considerably as a means of word formation in scientific texts in the mid-17th century. For the identification that affixation rises considerably as a means of word formation in scientific texts in the mid-17th century. For the identification of further linguistic features possibly involved in denser encoding, we draw, on the one hand, on existing literature (e.g. Harris, 1991) and, on the other hand, on exploratory data-mining techniques (e.g. pattern mining as in Vreeken, 2010).

In the poster, we show the corpus-building process and selected analyses of diachronic development in the RSC with dedicated visualizations (Fankhauser et al., 2014).

- Baron, A. and Rayson, P. (2008). VARD 2: A tool for dealing with spelling variation in historical corpora. In Proceedings of the Postgraduate Conference in Corpus Linguistics, Birmingham, UK.

- Cockburn, A. (2001). Agile Software Development. Addison-Wesley Professional, Boston, USA.

- Evert, S. and Hardie, A. (2011). Twenty-first century Corpus Workbench: Updating a query architecture for the new millennium. In Proceedings of the Corpus Linguistics Conference, Birmingham, UK.

- Hardie, A. (2012). International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17(3): 380-409. CQPweb – combining power, flexibility and usability in a corpus analysis tool.