Authors: Connie Lee Lester

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: History Harvest, community, democratization, RICHES, student projects

Harvesting History: Democratizing The Past Through The Digitization Of Community History

In 1993-94 Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen conducted a set of surveys that resulted in the publication of a seminal work titled The Presence of the Past. The team of historians, museum curators and students surveyed the American public about their interaction with history in order to understand “better ways of connecting academic historians with larger audiences” (Rosenzweig and Thelen, 1998). Their study concluded that Americans’ interest in history related to those events and groups that intersected with their own lives. They universally trusted museums because they could see the objects and images that were the “stuff” of history, but family stories, letters, and photographs defined history for most of the survey participants. With the publication of the survey, Rosenzweig and Thelen entered a historiographic discussion that centered on ways to incorporate history from the “bottom up” and to make the museum experience more interactive (Wallace, 1996; Hayden, 1997; Gardner and LaPaglia, 2004; Lewis, 2005; Gordon, 2010; Anderson, 2012; and Falk and Dierking, 2012).

Almost twenty years after Rosenzweig and Thelen conducted their survey, William G. Thomas, Patrick D. Jones and Andrew Witmer “advanced a movement to democratize and open history” with the founding of the History Harvest Project at the University of Nebraska (Thomas, Jones, and Witmer, 2013). Incorporating their own digital history experience into the classroom, Thomas, Jones, and Witmer developed student projects that operated at the “intersection of digital history and experiential learning.” Beginning in 2010 and continuing to the present, students worked with specific communities to organize History Harvest events at which they photographed objects and scanned images offered by individuals from their personal collections. The photographs and scans were uploaded into an Omeka database and organized into collections and digital exhibits. The project’s aim is to “make invisible archives and stories more visible.” The founders argue that to be successful, a History Harvest must be “organic, grassroots, and local.”

At the University of Central Florida (UCF), a Regional Initiative for Collecting History, Experiences, and Stories (RICHES™) Project has advanced the concept of student-public engagement through the use of History Harvests to collect “invisible archives and stories” by making the presentation of the digitized material interactive and democratizing the ability of site users to utilize the data in the collections to develop their own narratives. This transformational addition to the efforts to democratize history provides the user with the data, the tools to analyze the data, and the digital space to organize the data in order to create a narrative.

Working in Florida, students have access to a history that celebrates more than 500 years of interaction between Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans. The geographical position of Florida with its extensive coastline means that the history of the area has always been global. Interaction between the people of Caribbean Islands and those living in Florida pre-dated European claims for the region and expands the scope of scholarship. Successive waves of Spanish, French, British and American settlers altered the landscape and created new borderlands that continued until well into the twentieth century. Currently, the third most populous state in the nation, with an economy that ranges from agriculture to tourism to space exploration and high tech industries, Florida’s history is deep, diverse, and largely unexplored.

Students in graduate classes in Public History at UCF have completed three History Harvests and three additional Harvests are planned for 2016. The largest of the completed Harvests was accomplished through a partnership between the Introduction to Public History class, the Oviedo (Florida) Historical Society and a RICHES partnership tech firm, EZ-Photo-I/O Track. The students worked with the historical society to understand the history of the 137-year-old agricultural community that was transformed by the founding of UCF and the influx of thousands of students and faculty only three miles from the center of town. Based on the information provided by the historical society and a National Endowment for the Humanities-funded, society-published book (Adicks and Neely) the students conducted sixteen oral histories with descendants of the original settlers. In order to generate community awareness of the upcoming History Harvest students participated in public events and obtained permission to post information on the community and historical society social media sites. Building on the planning documents produced by previous student-led History Harvests, they organized the release forms, prepared to obtain the stories associated with items brought for scanning, and worked with EZ-Photo staff to facilitate the scanning process. More than 500 images, documents, three dimensional items, pamphlets, and scrapbooks were scanned on the day of the History Harvest. They told the story of citrus grove owners, farm laborers and fruit packers, migrants and immigrants to the community, schools, churches, and community social life.

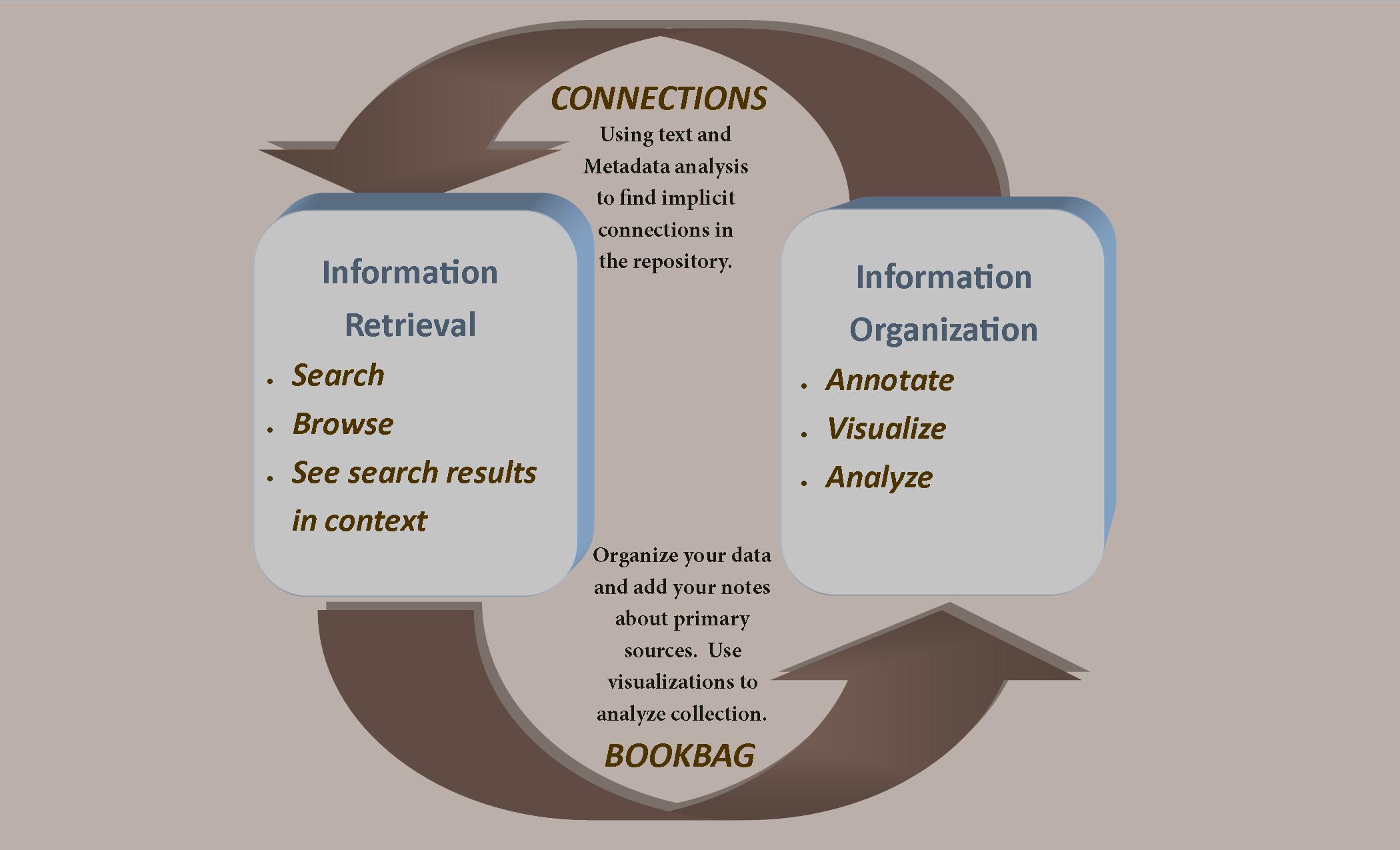

The UCF/RICHES History Harvest pushed the use of the collected data to a new, level by placing the material in RICHES Mosaic Interface™ https://richesmi.cah.ucf.edu . RICHES MI was initially created with the help of a National Endowment for the Humanities Startup Grant, and is an Omeka archive with multiple custom plugins and a front end that is a unique mechanism for searching the archive. RICHES MI users can search the database using natural language, tags, and topics, and browse by collection categories to maximize their search results; analyze the results of their search using the RICHES-developed “Connections” feature to show the relationship between the returned item and other items in the database; and visualize their results on a Google map and through digital exhibits, map overlays, and other visualizations. Users can save their search results in a Bookbag where they can annotate individual items, store items in folders, map the items collected in folders on a Google map and a timeline, and analyze the connections between items in the folders. They can also develop a narrative using the story board feature to organize their data. Finally, a search in the Omeka archive provides the user with links to digitized primary and secondary sources relevant to the individual object as well as links to other databases or websites that might be useful to the researcher.

Student Harvests, like their counterparts elsewhere, also create digital exhibits to organize the collected images and documents into an interpretative narrative. Faculty and students gain much through their participation in the History Harvests. Students acquire digital skills in metadata writing, archiving and exhibit creation; they learn to conduct oral histories and plan events; and they develop an understanding of the connection between local history and national/global issues. Each student’s work is cited by name in the metadata and in digital exhibits. Faculty participants are organizing larger projects (i.e. Parramore Project and Glass Bank Project) that include History Harvests and are expected to result in scholarly and pedagogical publications.

The next three projects, which are funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities “The Common Good: The Humanities in the Public Square” grant, will push the boundaries of History Harvests further: students will be using the oral histories and the collections obtained through History Harvests to produce a documentary film on an African American community’s struggles with urban development, to understand a coastal community’s relationship to an iconic building, and to provide evidence for two MA thesis projects dealing with Orlando’s LGBTQ community. The African American community project pairs students in an undergraduate history class with students at a predominantly black high school to explore changes that the construction of public buildings, entertainment and sports venues, an interstate highway, and the proposed expansion of UCF to a downtown campus have had on what was once a vibrant and cohesive African American community. The material collected will be used by a second undergraduate Honors class to produce a documentary film. This will be the fourth student produced film supervised by the course faculty. The second History Harvest will focus on an iconic building, the so-called Glass Bank, in Cocoa Beach, Florida. Constructed in the 1960s, the Glass Bank was demolished in 2014, but not before a partnership between RICHES and the Institute for Simulation and Training produced a 3D scan of the building. Recreated as it existed in 1963, the Glass Bank will serve as a vehicle for collecting images, artifacts and stories about the building as a center of community activity and economic development. See the video of the 3D scan https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DtVETzCND4M Finally, students will work with the GLBT Virtual Museum and the Orange County Regional History Center to harvest images, oral histories, and artifacts that tell the story of the gay destination, Parliament House, and the effect of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Orlando.

The RICHES project builds upon the insights of Public History scholarship and Digital scholarship to understand the complex past of local communities and to connect those histories to larger narratives. Using History Harvests to build a bridge between individuals, families, and local museums and historical societies and the academic community of students and faculty provides a service to the public and experiential learning for students. Awareness of the interaction between local and the national/global events enables students to consider their own scholarship in new ways. Placing the material harvested in an interactive database like RICHES Mosaic Interface democratizes the history collected by providing context, analytical tools, and space for organizing personal narratives.

- Wallace, M. (1996). Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory. Philadelphia, PA.

- Hayden, D. (1997). The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA.

- Adicks, R. and Donna N. (1998). Oviedo: Biography of a Town. Ovideo, FL.

- Rosenzweig, R. and Thelen, D. (1998). The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. New York.

- Gardner, J. B. and LaPaglia, P. S. (eds). (1999), (2004). Public Essays from the Field. Malabar, FL.

- Lewis, C. (2005). The Changing Face of Public History: The Chicago Historical Society and the Transformation of an American Museum. DeKalb, IL.

- Gordon, T. S. (2010). Private History in Public: Exhibition and the Settings of Everyday Life. Nanham, MD.

- Anderson, G. (ed). (2012). Reinventing the Museum: The Evolving Conversation on the Paradigm Shift. Lanham, MD.

- Falk, J. H. and Dierking, L. D. (2012). The Museum Experience Revisited. Walnut Creek, CA.

- Thomas, W. G., Jones, P. D. and Witmer, A. (2013). “History Harvests: What Happens When Students Collect and Digitize the People’s History?” Perspectives on History: The Newsmagazine of the American Historical Association (January 2013) https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-2013/history-harvests (accessed October 15, 2015).