Authors: Charles van den Heuvel, Florentina Armaselu

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: interface design, scholarly editing of text and image, Z-text model, scalable reading, digital hermeneutics

Invisible Cities In Literature And History: Interfaces To Scalable Readings Of Textual And Visual Representations Of The Imaginary

Introduction

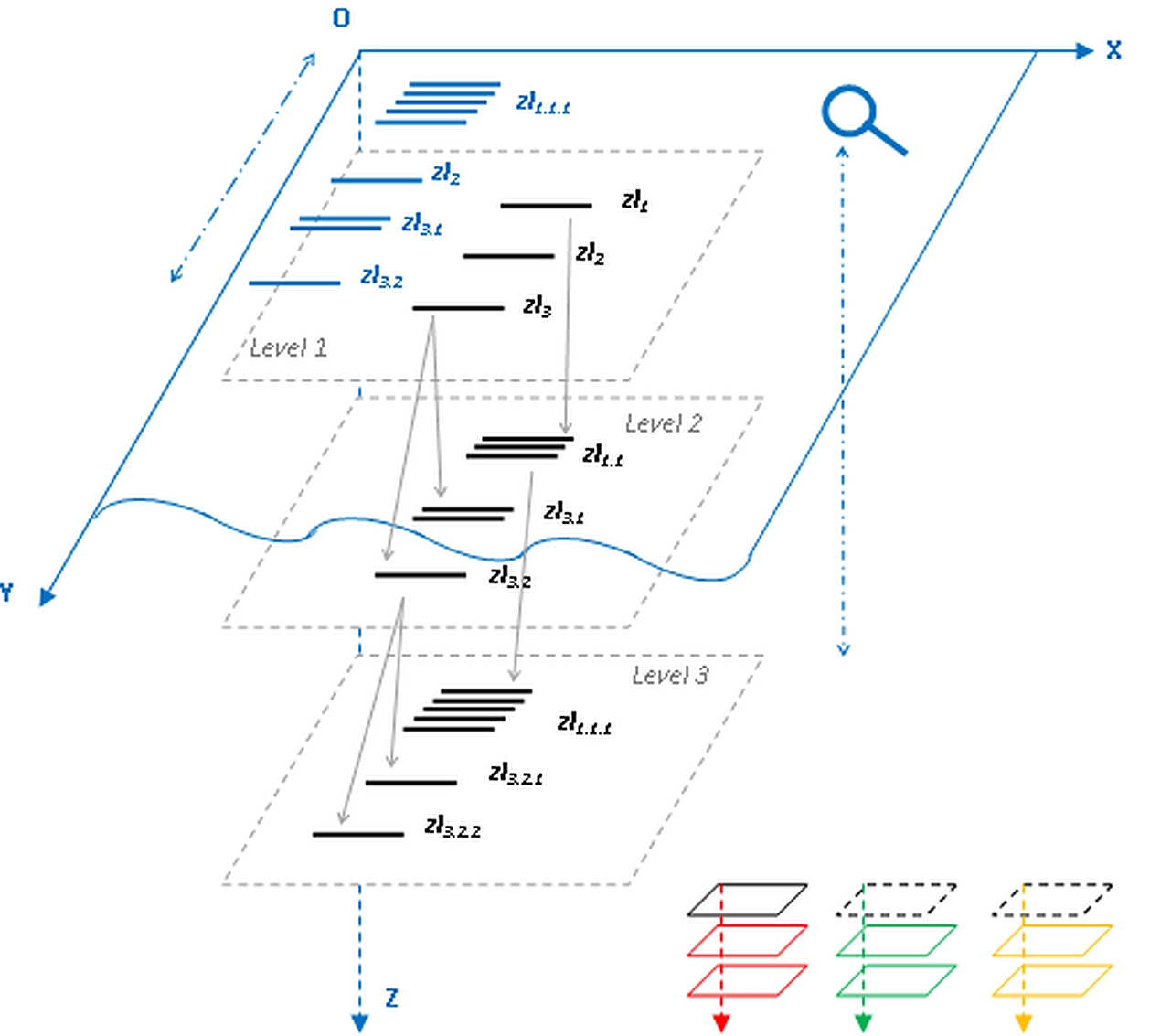

At the DH2014 conference it was explained how the ZoomImagine software (Z-editor) allows zooming on units of text and contextual information (z-lexias) in order to explore layers of meaning that support critical readings of literature (Armaselu 2014). Changing perspective or analytical viewpoints by using different types of “magnifying glass” is also possible (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Z-text layout. Levels of z-lexias (center). Changing perspective (bottom right)

In this study the results of two experiments will be discussed in which the Z-editor was used to explore cross-overs between text and image and history and literature in descriptions of imaginary cities and imaginary depictions of existing cities. The first case concerns readings of the Invisible Cities (1972) in which Italo Calvino (1923-1985) described Marco Polo’s accounts of visits to cities to Kubla Kahn, Emperor of the Tartars. The second one discusses designs for and historical depictions of the citadel of the city of Groningen in the Netherlands in an atlas of the Flemish engineer Pierre Lepoivre (1546-1626). We will demonstrate that the Z-text model is both suitable for analyzing critical readings and artistic impressions of the Invisible Cities as for assessing different levels of historical evidence of visualizations, such as maps, drawings and designs of existing cities. Furthermore, it allows for navigating in an associative way through imaginary cities of which features might have inspired both Calvino’s literary writings as Lepoivre’s designs. Contemporary artists still inspired by Calvino seem to delve into a collective visual memory of “cities”, in a way Renaissance engineers linked their designs to representations of ideal cities and new fortress towns, from Campanella’s City of the Sun to Zamośź in Poland. The Z-text model might stimulate to explore digital past and future identities of imaginary and real cities. We will conclude with a discussion of the potential of the Z-editor interface for general debates within the digital humanities.

The Invisible Cities of Italo Calvino

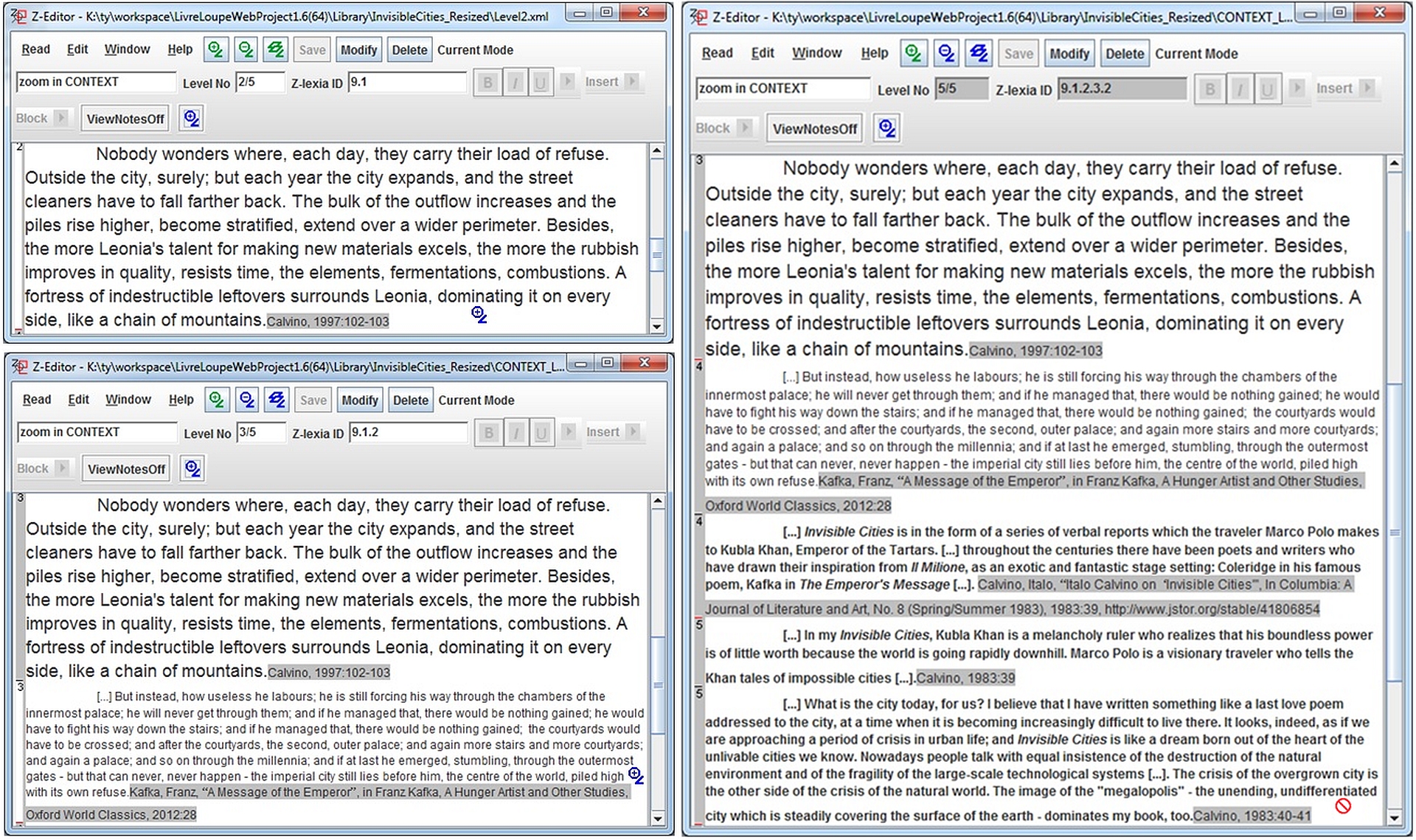

The publication of Le Città Invisibili in 1972 by Italo Calvino was directly followed by comments by literary critics and by visualizations of artists inspired by the poetical descriptions of the imaginary cities in the imageless book. The division into 11 themes associated with the city that return each 5 times in the book -City and Memory, City and Desire, City and Signs, Thin Cities, Trading Cities, Cities and Eyes, Cities and Names, Cities and the Dead, Cities and the Sky, Continuous Cities and Hidden Cities- has resulted into various interpretations of these imaginary urban spaces, such as “rhizomatic space” Kerstin Pilz (2003) and “city of strata” Sambit Panigrahi (2014). The zooming functionalities of the editor and Z-text model make it possible for instance to analyze Calvino’s description of the continuous city of Leonia that each days breaches through its boundaries of deposited waste at its circumference with these contemporary interpretations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Invisible Cities Z-text. Level 1 (left), 2 (right). Calvino's text unfolding along different lines of “stratification”, the "new-old" divide and the "textual-visual" metamorphosis (the visual "becoming" of the text). The first level (left) contains fragments (z-lexias) conveying the meaning of "new" (through words like "new", "renew"). By zooming-in (right), further elements from deeper levels can be surfaced, i.e. fragments entailing the idea of accumulation of "old" (including words such as “yesterday”, "past", “residue”, “remains”, "garbage", "refuse") or visual representations not belonging to the original text but imagined by various artists.

Another "rhizomatic" expansion imagined via the model - along with the "contextualization" line ‐ enables other readings of Calvino’s work, both by critics and himself. Calvino in some occasions looks through the lens of the writer and in other moments through the eyes of the reader or editor and states “that the author’s view no longer counts” (Baldi, 2015; Calvino, 2015: 41-42). Calvino sometimes puts the Invisible Cities directly into context by referring to works that similarly are inspired by Marco Polo’s travels, such as the poem Kubla Kahn (1798) of Samuel Taylor Coleridge or The Message from the Emperor (1919) by Franz Kafka. In other occasions references are indirect, for example when Calvino notes that the atlas of Kubla Kahn contains images of “lands visited in thought, but not yet discovered or founded: New Atlantis, Utopia, the City of the Sun [..]” (Calvino, 1997: 147). On a more detailed level the possibility of sideways movements becomes important when Calvino reacts to all those critics who underlined the importance of the closing sentence by claiming that the Invisible Cities is “a many facetted book” with “various possible ‘conclusions’” (Calvino, 1983: 41). By combining the zooming functionality with the representation of contextual information a Z-text becomes a multidimensional space of analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Invisible Cities Z-text. Level 2 (top left), 3 (bottom left), 5 (right). “Multidimensional” exploration by switching perspectives. One can zoom-in to get the visual representation of a fragment (compare Figure 2) or, instead, change the perspective and zoom-in with a contextual magnifying glass and expand Calvino's text with Kafka's or Calvino's own comments on Invisible Cities (Kafka, 2012; Calvino, 1983).

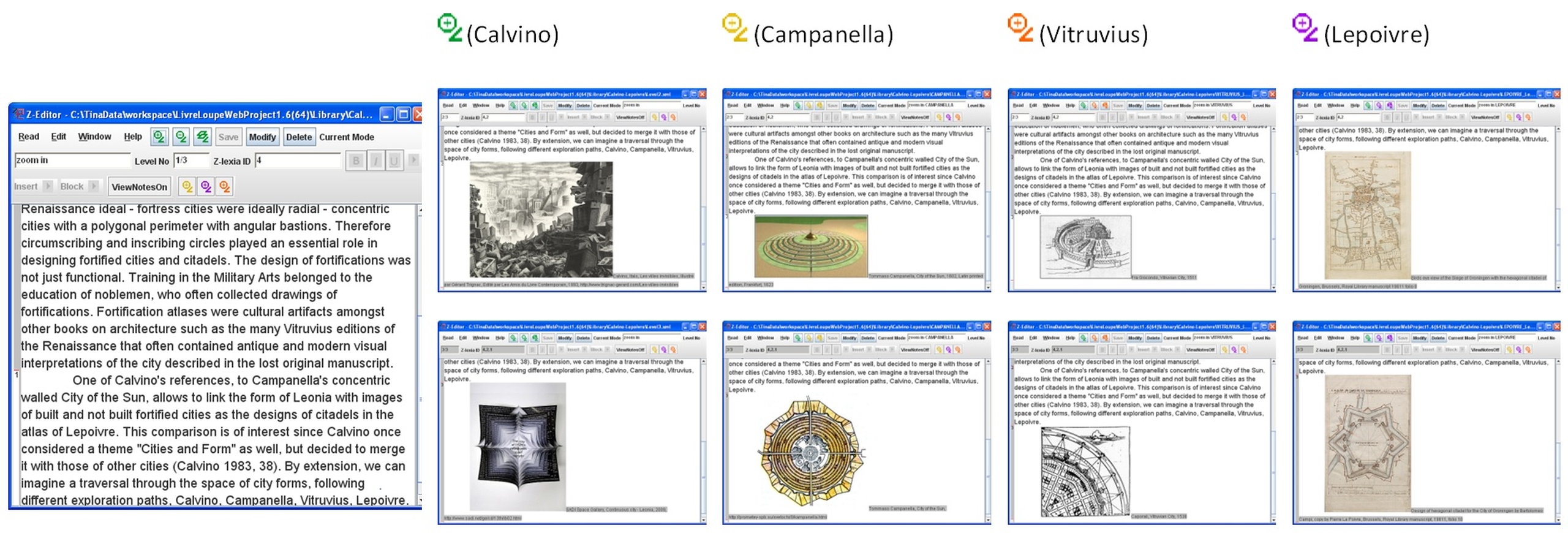

Such an interface may be useful for the analysis of the Invisible Cities when Calvino observes: “And yet, all these pages put together did not make a book: for a book (I think) is something which has a beginning and an end [..] It is a space which the reader must enter, wander round, maybe lose his way in, and eventually find an exit, or perhaps even several exits, [..]” (Calvino, 1983: 38). If we enter our concentric city of Leonia again, new associative perspectives pop up. We recognize Calvino’s reference to Kafka’s story of the Emperor’s messenger wanting to report about the death of Kubla Kahn by trying - breaking through the walls surrounding the palace, “the center of the world, piled high with its own refuse.” (Kafka, 2012: 28) However, another of Calvino’s references, the one to Campanella’s concentric walled City of the Sun allows to link the form of Leonia with images of built and not built fortified cities that are related to our second experiment dealing with levels of historical evidence of designs of citadels in the atlas of Lepoivre (compare Figure 5). This comparison is of interest since Calvino once considered a theme “Cities and Form”, but decided to merge it with those of other cities (Calvino, 1983: 38).

Imaginary Depictions of An Existing City: Groningen (Netherlands)

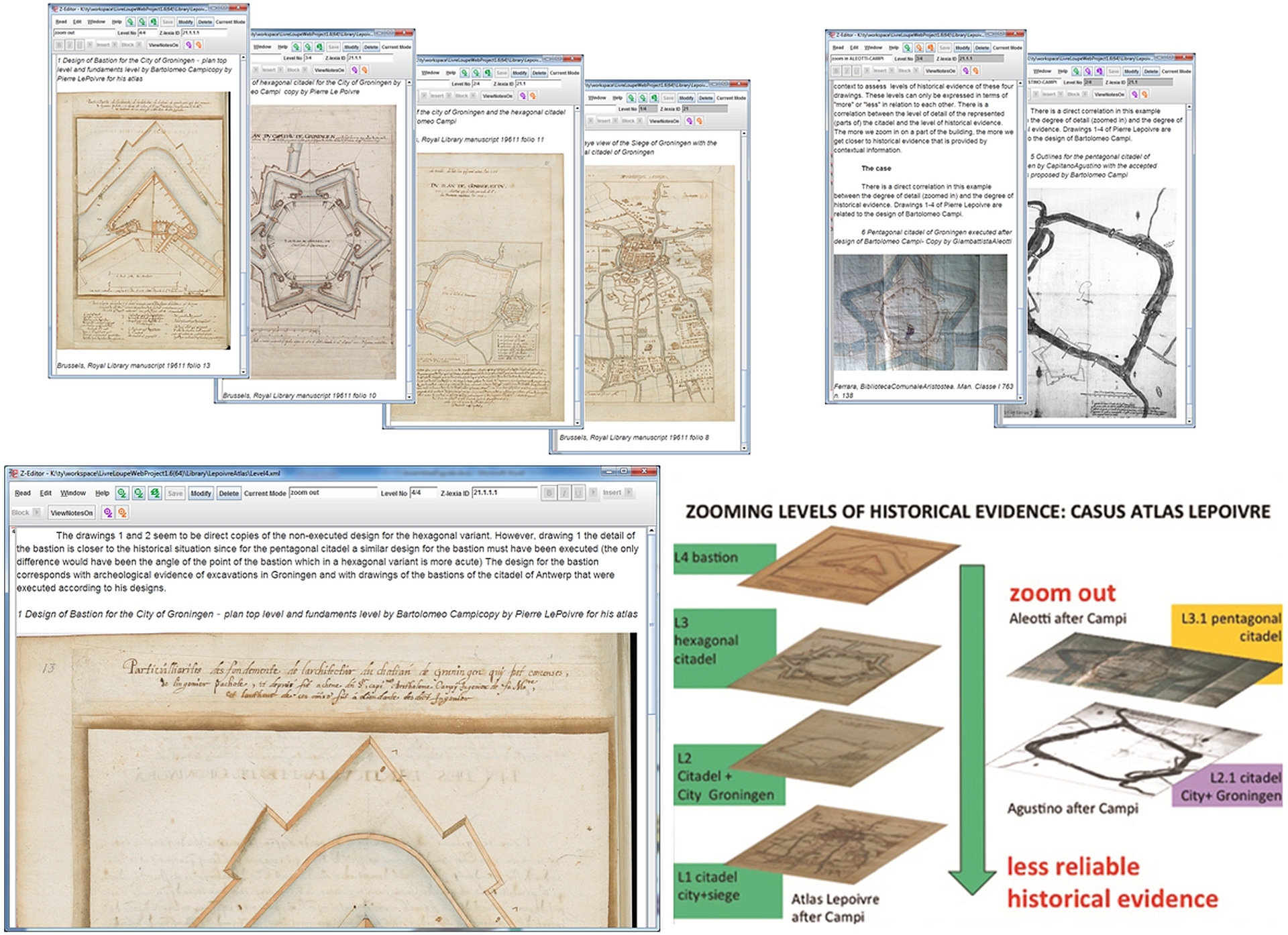

Renaissance ideal-fortress cities were ideally radial-concentric cities with a polygonal perimeter with angular bastions. Therefore circumscribing and inscribing circles played an essential role in designing fortified cities and citadels. The design of fortifications was not just functional. Fortification atlases were cultural artifacts amongst other books on architecture such as the Renaissance Vitruvius editions that often contained visual interpretations of the city described in the lost original manuscript. In this context also the four drawings based on the designs of the Italian engineer Bartolomeo Campi of the city and citadel of Groningen in the Atlas of Lepoivre of ca. 1624 must be seen (Heuvel, 1994: 1998) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Lepoivre Atlas. Z-text layout (top), level 4 (bottom left); interpretation (bottom right). The imaginary space of historical representation can be traversed through layers corresponding to decreasing levels of historical evidence (top left) or to different perspectives (Campi/Aleotti and Agustino variants, top right).

The detail of the bastion was probably directly copied after Campi’s design of 1570 (Heuvel, 1994). Lepoivre included a drawing after Campi’s design for a hexagonal citadel, but a pentagonal one was executed. The third drawing shows Groningen with the hexagonal citadel that never existed in that form and the fourth as a part of the Siege of Groningen in 1594, when the citadel that existed was already dismantled (Heuvel, 1998: 200). The Z-editor not only allows moving along the four different levels of historical evidence, but also to position these drawings (that we could call nowadays historical falsifications) between more and less imaginary depictions of existing and non existing cities (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Imaginary Cities Z-text. Level 1 (left), 2 (top right), 3 (bottom right). Traversal through the space of forms, following multiple exploration paths and connecting imaginary cities in literature (Calvino, Campanella) and in architectural treatises and theory (Vitruvius) with imaginary representations of existing cities in design (Lepoivre).

The Z-text model and the digital humanities

The Z-text model meets a wide array of new reading and analysis practices discussed in relation to the digital humanities. While the zooming function supports bridging distant and close reading by scalable reading (Mueller, 2012) the combination with contextualization on the various planes to read text and image from various perspectives coincides with notions of deep reading (Birkets, 1994). This combination allows for the creation of multiple levels of meaning and supports a continuously process of reinterpretation from multiple perspectives, contributing this way in developing digital hermeneutic methods (Capurro, 2010).

- Armaselu, F. (2014). The Layered Text. From Textual Zoom, Text Network Analysis and Text Summarisation to a Layered Interpretation of Meaning. Digital Humanities 2014 Conference Abstract EPFL-UNIL, Lausanne, Switzerland, pp. 79-82. http://dharchive.org/paper/DH2014/Paper-515.xml. (accessed 2 March 2016)

- Baldi, E. (2015). lL’ ochio che scrive. La dinamica dell’ imagine autoriale di Calvino nella critica italiana, Incontri 2015, 1: 22-33 www.rivista-incontri.nl (accessed 2 March 2016)

- Birkerts, S. (1994). The Gutenberg Elegies: the Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age, Faber and Faber, Boston (MA).

- Capurro, R. (2010). Digital Hermeneutics: An outline. AI and Society, 2010, 35(1): 35-42, http://www.capurro.de/digitalhermeneutics.html.

- Calvino, I. (1972). Le città invisibili, Einaudi, Turin.

- Calvino, I. (1983). Italo Calvino on ‘Invisible Cities’. Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, 8: 7-42.

- http://www.jstor.org/stable/41806854 (accessed 2 March 2016).

- Calvino, I. (1997). Invisible Cities. Translated from the Italian by William Weaver. London: Vintage Books.

- Heuvel, Charles van den (1994). Bartolomeo Campi successor to Francesco Paciotto. A different method of designing citadels: Groningen and Flushing. In: Architetti e ingegneri militari italiani all'estero dal XV al XVIII secolo. Livorno-Roma, pp. 153-67.

- Heuvel, Charles van den (1998). Pierre Le Poivre (1546-1626). Engineer of the King and the Representation of Architecture, In W. Thomas, L. Duerloo, (Eds.), Albrecht and Isabella. Essays. Turnhout, pp. 198-202.

- Kafka, F. (2012). A Message of the Emperor. In Franz Kafka, A Hunger Artist and Other Studies. A new translation by Joyce Crick, World Classics 2012, 28. (First published 1919).

- Lepoivre, P. (1624). Les Plans des Villes des Païs de Hennault, d’ Artois, de Breband, très noblemen descripts a la plume par l’ architecte Pierre Le Poivre etc. Brussels, Royal Library Albert I, Ms. 19611.

- Mueller, M. (2012). Scalable Reading. Dedicated to Data, digitally assisted text analysis, https://scalablereading.northwestern.edu/scalable-reading/ (accessed 2 March 2016).

- Panigrahi, S. (2014). Cities as Strata in Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities. The Explicator, 72(1): 23-7, doi: 10.1080/00144940.2013.875873.

- Pilz, K. (2003). Reconceptualising Thought and Space: Labyrinths and Cities in Calvino's Fictions. Italica, 80: 229-42, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30038769 (accessed 2 March 2016).

- ZoomImagine: www.zoomimagine.com (accessed 2 March 2016).