Authors: Mattia Egloff, Davide Picca, Kevin Curran

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: cognitive computing, IBM Watson, personality, Shakespeare, main characters

How IBM Watson Can Help Us Understand Character in Shakespeare: A Cognitive Computing Approach to the Plays.

1. Introduction

The study of an individuals’ personality traits is a new line of research that emerged only recently, primarily through the investigation of dialogue systems and weblogs (Gill et al., 2012; Konstantopoulos, 2010; Mairesse and Walker, 2006; Mairesse and Walker, 2007). This paper proposes a novel application for personality classification by leveraging on cognitive computing research and by exploiting the poetic production of theatrical plays. More specifically, this research is circumscribed to the analysis of Shakespeare’s tragedies, which offer a rich spectrum of characters for a detailed and in-depth study. This research does not aim at introducing the innovative technological aspects of personality classification in cognitive computing but rather at employing such technology in the study of English literature, and analyse some implications that arise from the results.

Before presenting the core of this research, we outline the psychological theory of the “Big Five,” its implementation as well as its extension in IBM Watson. Successively, in Section 2, we introduce the data used, the method applied and the results obtained in our analysis. In Section 3, we discuss some useful applications and extensions for literature scholars. Finally, we conclude by presenting some considerations for future research.

2. IBM Watson and the Big Five personality insight

Cognitive computing originated in the early 60s, however, it has been improved dramatically in recent years, achieving significant success through the launch of IBM Watson in 2010. IBM Watson simulates human cognitive systems by implementing advanced natural language processing, information retrieval, knowledge representation, automated reasoning, and machine learning technologies to the field of open domain question answering (Ferrucci et al., 2010; Ferrucci, 2012). Among human cognitive activities, one of the most employed is the capability to understand and forecast other people’s personalities. As described in the Big Five theory (Norman, 1963) formulated by scholars in psychology, each individual presents a different aptitude in identifying characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving in others. The Big Five theory is the main theory on which IBM Watson has been built; it distinguishes between five broad dimensions underlying an individual’s personality, namely openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

- Openness mirrors the level of scholarly interest, imagination and an inclination for oddities.

- Conscientiousness is the propensity to be reliable, to show self-control and act obediently.

- Extroversion comprises vitality, positive feelings, confidence, amiability and the propensity to look for incitement in the organization of others.

- Agreeableness is the inclination to be merciful and agreeable as opposed to suspicious and adversarial towards others.

- Neuroticism is the propensity to encounter obnoxious feelings, for example, outrage, uneasiness, wretchedness, and powerlessness.

Next to the Big Five personalities, IBM Watson takes into account the concept of “Needs,” which are described by the literature as universal needs shared by all human beings (Ford, 2005; Kotler and Armstrong, 2010). Along with Big Five and Needs, IBM Watson takes into account the psychological concepts of Values which are defined as “desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives” (Schwartz, 2006). As mentioned on the IBM Watson website 1 “Schwartz summarizes five features that are common to all values: (1) values are beliefs; (2) values are a motivational construct; (3) values transcend specific actions and situations; (4) values guide the selection or evaluation of actions, policies, people, and events; and (5) values vary by relative importance and can be ranked accordingly.”

3. Method and Results

Our objective consists in comparing the personality of the main characters of three Shakespeare’s tragedies in a positive versus negative sentimental context. To establish these contexts we use the work of Nalisnik et al. (Nalisnick and Baird, 2013) on sentiment analysis to divide the characters of the play into two groups. The first group is composed of those characters towards which the main character expresses mainly positive sentiments; the second group comprises those characters towards which the main character expresses mainly negative sentiments. In practice, we extracted each instance of continuous speech from the plays 2. The groups divisions take in account the sentiment valence and the minima of sings that the IBM Personality Insights needs to produce significant results and then assumed that each speech act by one speaker was directed towards the character that spoke immediately before him. We used this assumption to replicate Nalisnik’s data but, as he pointed out in his paper, “This assumption does not always hold; it is not uncommon to find a scene in which two characters are expressing feelings about someone off-stage.”. We retrieved the sentiment valences for each main character 3, reported in the following tables:

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By assembling all continuous speech sequences directed to the characters in the different groups, we created two text groups: the first group contains all lines of the main character towards the others when expressing positive sentiments, the second group includes those speech sequences characterized by a negative sentimental connotation. We performed this task for three main characters, more specifically Hamlet, Othello and Macbeth. In Table , the positive and negative word counts for these text assemblies are plotted.

| Positive | Negative | |

| Hamlet | 6655 | 3455 |

| Othello | 3424 | 2407 |

| Macbeth | 1293 | 1852 |

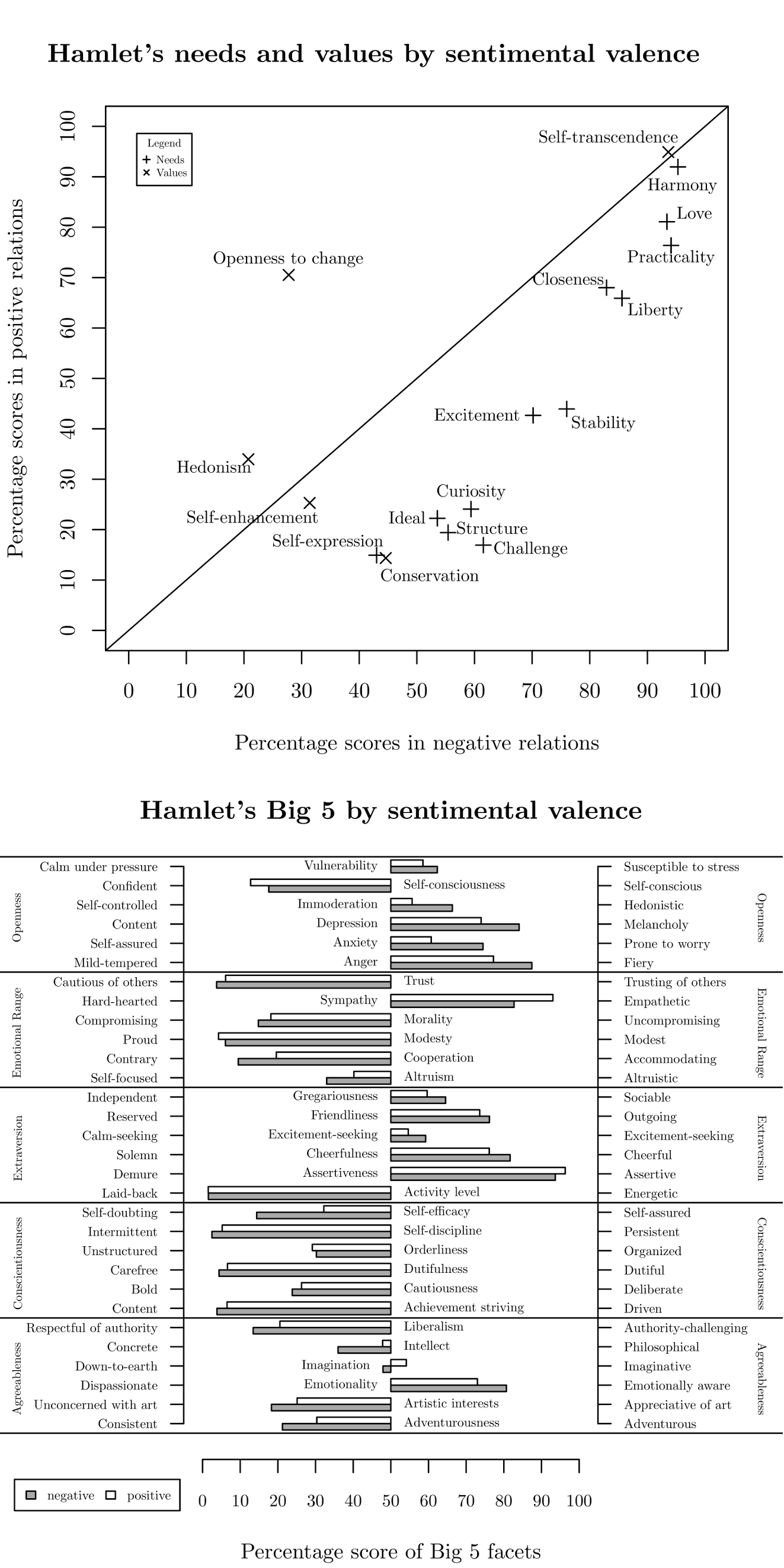

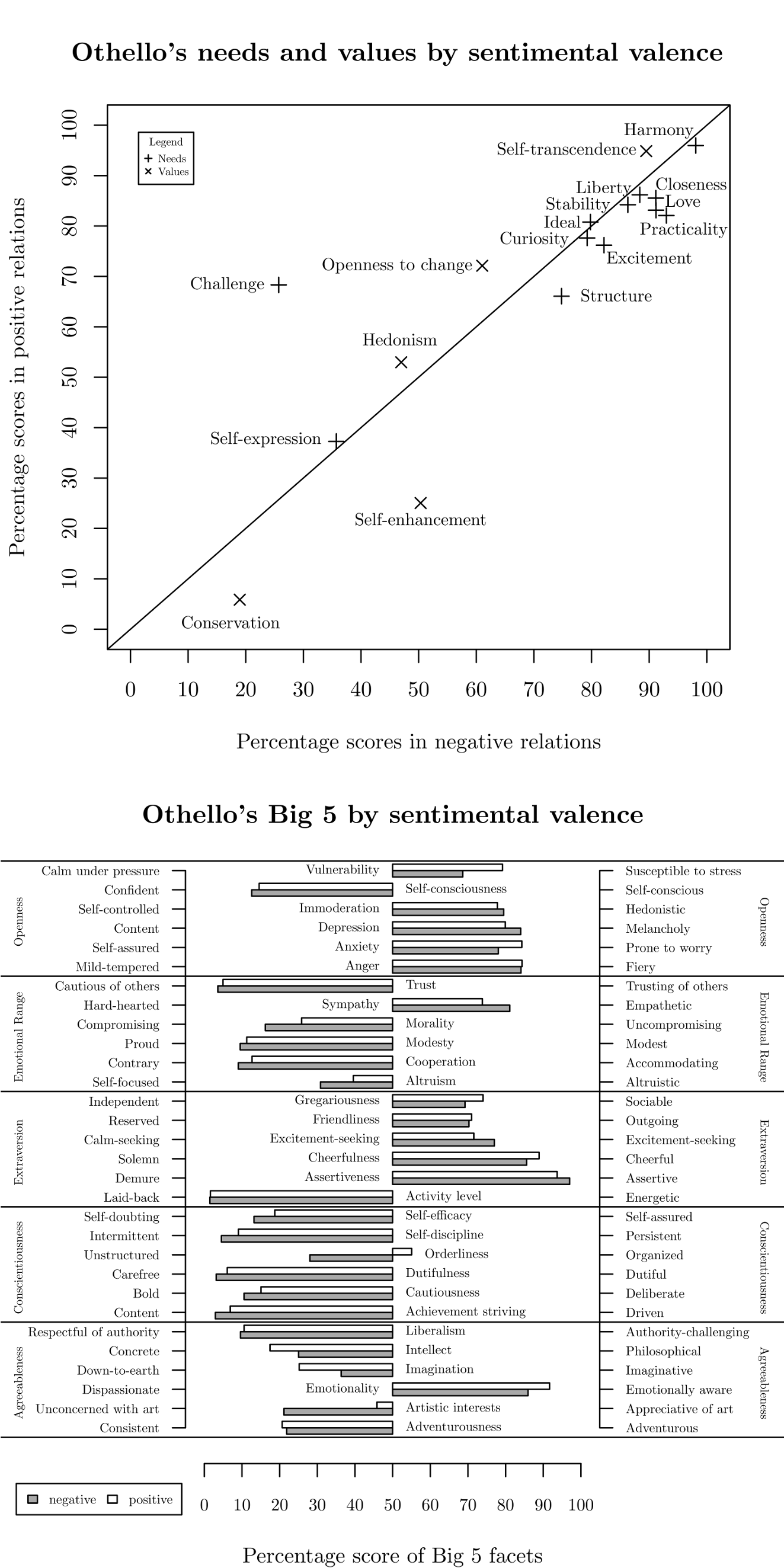

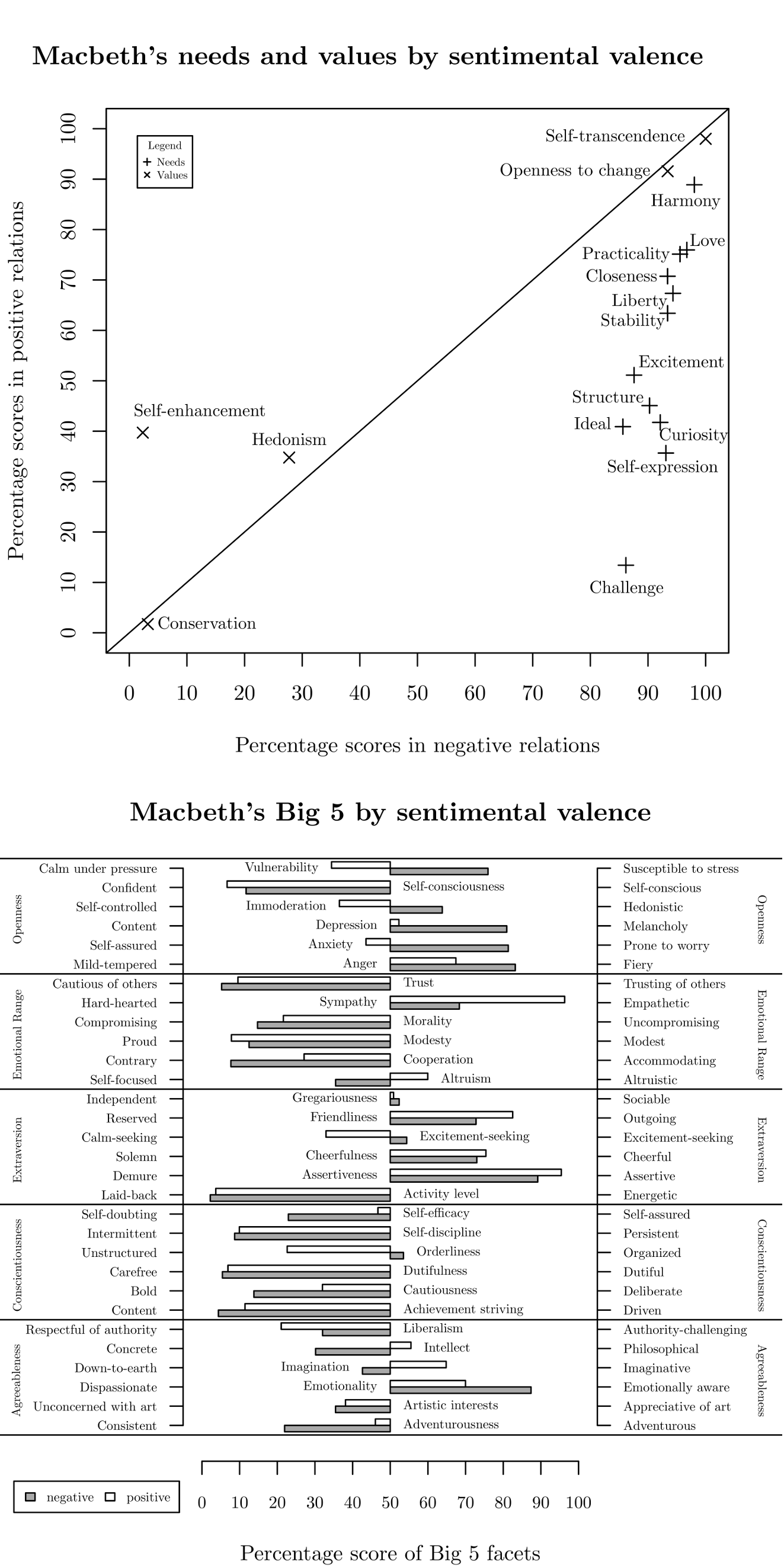

Finally, we used IBM’s personality insight service to create personality profiles for each of the main characters based on the positive and negative texts. Figures 1, 2 and 3 represent the distribution of needs and values with respect to the positive or negative sentimental valence. Points on line represent independence with respect to the latter. For needs and values falling below this line, the distribution is characteristic for the expression of negative sentiments. We also created personality graphs with respect to the groups. Although they are calculated as percent of a given facet (as indicated by the x axis), the facets vary between low and high values. Thus, the bars in the graph begin at 50% and can either be low (to the left) or high. A score of 50% signifies that the facet is balanced.

4. Some Insights and Discussion

A quantitative approach to character clearly generates a comparatively large amount of linguistic data. The question is, how are we to use this data? What can such an approach offer Shakespeare studies and the humanities more broadly? How does the data we have generated contribute to the critical conversation in a sub-field like character criticism (Hazlitt, 1845; Bradley, 1992; Desmet, 1992; Yachnin and Slights, 2009) which has such a long and distinguished history. There are two answers to this question. First, our analysis shows in a more concrete and detailed way than ever before, the close relationship between character and language, something easy to forget in the context of a representational practice like theatre which is so dependent on non-linguistic features, such as gesture, costume, and stage properties. Playgoers, however, do not just see character; they also hear it. And in the modern humanities classroom, they read it. Accordingly, words play a significant role is crafting what we would now call the “personalities” of Shakespeare’s stage. Our approach offers a new means of isolating and analyzing these verbal features of character. The second way in which our work contributes to Shakespeare studies has to do with something our data does not tell us. To understand what we mean by this, consider for a moment why it is that the words associated with some characters generate a personality profile that anyone familiar with the plays knows does not quite fit? Why, for example, does Hamlet have a verbal data set that makes him seem much more serious and honor-driven than he actually is It is because the technology we are using is not capable of accounting for context and therefore cannot detect things like irony and wordplay, two things that are extremely important components of the way language articulates character and personality. While this may be viewed as a methodological weakness from the perspective of information technology, it is a great strength from the perspective of the humanities. For it is precisely at those moments that the data fails to deliver coherent results that we are forced to ask compelling questions about language and art: why do words that seem to mean one thing have the opposite effect on stage? What is the relationship between the literal and implied meanings of words in the constitution of dramatic character? In the end, this facet of our contribution to Shakespeare studies illustrates something important not just about our project specifically, but also about the digital humanities generally: the value of applying computational technology to literary texts lies not in the promise of “better data” or irrefutable “facts,” but rather in the way such technology returns us again and again to the fundamental humanist questions that help us understand how literature and art work 4.

5. Future Research

In this paper we introduced novel techniques based on cognitive computing to get an understanding of characters in Shakespeare’s plays. This research explores newway of computer-assisted methods for the investigation of literature. Nonetheless, some technical issues need to be overcome in order to improve the quality of this new methodology. First, an improved methodology to outline the sentiment polarity needs to be developed. Second, the low representativity of IBM’s personality model needs to be enhanced in order to catch literary phenomena in sources such as Twitter, Wikipedia, and other such corpora. Thus, recreating a personality insight service based on a literary work corpus would surly enhance the results of our method.

- Bradley, A. C. (1992). Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. 3rd ed. New York: St. Martinis Press.

- Desmet, C. (1992). Reading Shakespeare’s Characters: Rhetoric, Ethics, and Identity. Amherst: Univ of Massachusetts Press.

- Ferrucci, D. A. (2012). Introduction to ‘This is Watson’. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 56(3): 1 doi:10.1147/JRD.2012.2184356.

- Ferrucci, D. A., Brown, E. W., Chu-Carroll, J., Fan, J., Gondek, D., Kalyanpur, A., Lally, A., et al. (2010). Building Watson: An Overview of the DeepQA Project. AI Magazine, 31(3): 59–79.

- Ford, J. K. (2005). Brands Laid Bare: Using Market Research for Evidence-Based Brand Management. Wiley https://books.google.it/books?id=0Q3OClLh6UsC.

- Gill, A., Brockmann, C. and Oberlander, J. (2012). Perceptions of Alignment and Personality in Generated Dialogue. INLG 2012 Proceedings of the Seventh International Natural Language Generation Conference. Utica, IL: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 40–48 http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W12-1508.

- Hazlitt, W. (1845). Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays. Boston: Wiley and Putnam.

- Konstantopoulos, S. (2010). An Embodied Dialogue System with Personality and Emotions. Proceedings of the 2010 Workshop on Companionable Dialogue Systems. Uppsala, Sweden: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 31–36 http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W10-2706.

- Kotler, P. and Armstrong, G. M. (2010). Principles of Marketing. (PRINCIPLES OF MARKETING). Prentice Hall https://books.google.it/books?id=5HkrAQAAMAAJ.

- Mairesse, F. and Walker, M. (2006). Automatic Recognition of Personality in Conversation. Proceedings of the Human Language Technology Conference of the NAACL, Companion Volume: Short Papers. New York City, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 85–88 http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/N/N06/N06-2022.

- Mairesse, F. and Walker, M. (2007). PERSONAGE: Personality Generation for Dialogue. Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics. Prague, Czech Republic: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 496–503 http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P07-1063.

- Nalisnick, E. T. and Baird, H. S. (2013). Character-to-character sentiment analysis in Shakespeare’s Plays.

- Norman, W. T. (1963). Toward an adequate taxonomy of personality attributes: replicated factors structure in peer nomination personality ratings. J Abnorm Soc Psychol, 66: 574–83.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Basic human values: Theory, measurement, and applications. Revue Française de Sociologie, 47(4): 249–88.

- Yachnin, P. and Slights, J. (2009). Shakespeare and Character: Theory, History, Performance and Theatrical Persons. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.