Authors: Agata Hołobut, Jan Rybicki, Monika Woźniak

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: film subtitles; dubbing; voice-over; stylometry, translation

Stylometry on the Silver Screen: Authorial and Translatorial Signals in Film Dialogue

Stylometry based on quantitative analysis of linguistic features such as most frequent words, lemmata, or parts of speech, is a time- and research-proven tool in authorship attribution and plagiarism detection, and is now also used in more general literary studies as part of the distant reading revolution. It has been particularly successful in grouping long texts by their authors in both supervised and unsupervised machine learning tests – and the appeal of this material to stylometrists is understandable in that novels are easily available and easily definable chunks of linguistic (and literary) material, and, despite rumors on the death of the author, most readily associated by the general reader with a single creative figure. And when they are not, discovering the fingerprints of more than one hand in collaborative works is another favorite pastime of stylometrists.

While perhaps equally avidly studied, the authorship signal in drama is often more problematic. This is probably why the most famous question, that of Shakespearean authorship, is so complex and so hotly contested – as evident, for instance, in a fairly recent debate (Craig and Kinney, 2009; Vickers, 2011; Hoover, 2012). Other difficulties in this genre include the “codification of … literary discourse” in certain literary periods and the fact that the same authors might write drama both in prose and in verse (Schöch, 2013, 2014); also, it may be supposed that, as dramatists create their characters through dialogue, there is a more or less conscious effort on their part to differentiate their style. This last phenomenon has also been researched in novels (Burrows, 1987) and translations of novels and drama, and the results could be equally problematic (Rybicki, 2006, 2007, 2008).

Even more distortion may be expected in a somewhat similar genre, that of film and TV dialogue – and its textual reflection in intralingual subtitles and interlingual translations. The final shape of filmic speech ascribed to a given screenwriter can be influenced by other agents, such as directors or actors. It can be further transformed in the process of intralingual subtitling, especially that performed by “fansubbers”, who do not necessarily reflect the exact dialogue spoken onscreen. This becomes even more of a problem in the case of interlingual translations, which by nature condense (subtitles, voice-over) or rework (dubbing) the original message, being at times anonymous versions of questionable quality (“fansubs”).

Quantitative methods have already found their way into audiovisual translation research (Pérez-González 2014; Baños et al., 2013), as exemplified by such projects as Pavia Corpus of Film Dialogue, used to examine sociolinguistic and pragmatic features of dubbed Italian (Freddi and Pavesi, 2009), or Forlixt1, a multimodal corpus which helps to investigate the interplay of verbal and non-verbal semiotics of the film (Valentini, 2006, 2008).

In comparison with the above attempts, our research was done on a specialized corpus of historical films and TV (mini)series. This choice was based on the assumption that the subgenre has unique characteristics which find reflection in film dialogue: namely, it authenticates the represented reality and it also adheres to the codes of realism existing in particular countries. This, in turn, made us look for the same phenomena in (English) originals and (Italian and Polish) translations, since translated dialogue, too, is shaped by stylistic necessities of the genre, culture-specific images of the past dominant in the target context, but also by norms and conventions of audiovisual translation in a given language/culture/country. The exact composition of the corpus is given in the table below:

| Original | Polish voice-over | Polish “official” subtitles | Polish fansubs | Italian dubbing | Italian “official” subtitles | Italian fansubs |

| The Tudors Season 1 (2005) | + | + | + | + | + | |

| The Tudors Season 2 (2007) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Elizabeth I (2005) (miniseries) | + | + | ||||

| Elizabeth (1998) | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Elizabeth. Golden Age (2007) | + | + | + | + | + | |

| The Other Boleyn Girl (2008) | + | + | + | + | ||

| The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) | + | + | + | + | ||

| Anne of a Thousand Days | + | + | ||||

| Wolf Hall (2015) | + |

From the point of view of film and audiovisual translation studies, our research project explores the concept of film/television genre and its distinctive features, focusing on the functions of film dialogue and linguistic/stylistic strategies used by screenwriters to fulfil them (Kozloff, 2000; Jaeckle, 2013). The first stage of our investigation consisted in a contrastive stylometric analysis of the extended Anglophone corpus, composed of both historical and non-historical film scripts, in order to verify our preliminary hypothesis about the genre-related specificity of film dialogue. We proceeded, then, to the analysis of parallel corpora of scripts in all available translations into Polish (voice-over, official and amateur subtitles) and Italian (dubbing, official and amateur subtitles). All this was done with several quantitative methods previously developed and used on other textual material, i.e. literary texts. In particular, frequencies of words from various frequency strata were compared between texts in each of the languages studied using the Delta procedure (Burrows, 2002). The analyses were performed with stylo (Eder et al., 2013), a package for R, the statistical programming environment (R Core Team, 2014), later also postprocessed with Gephi network analysis software (Bastian et al., 2009).

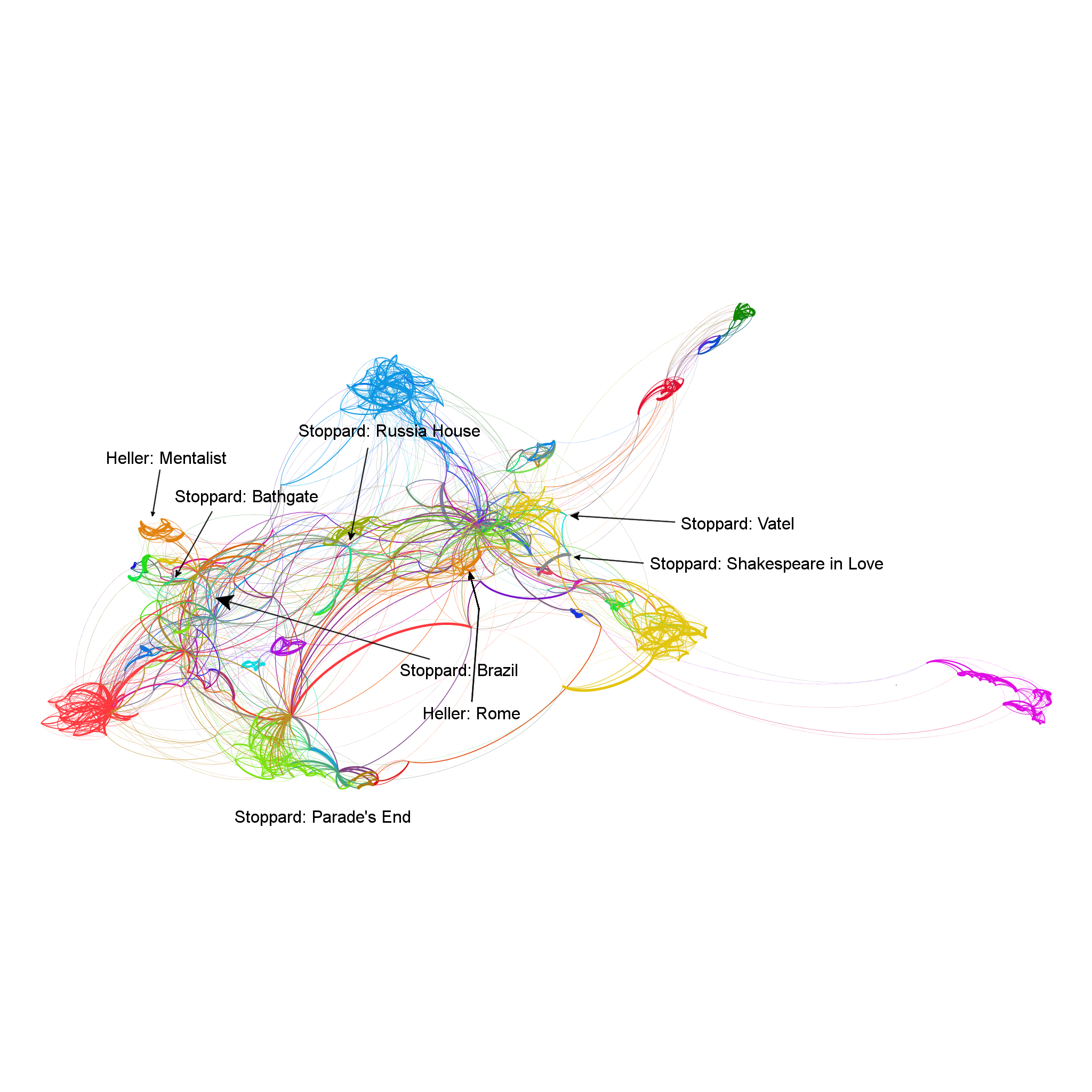

On the basis of these tests several observations could be made. As concerns the screenwriters, they tend to adapt the dialogues to the requirements of historical genre and the presented epoch. This is visible in Fig. 1, where the authorial signal seems to disappear whenever a given writer worked on two films and/or series set in different eras or belonging to a different, i.e. non-historical genre.

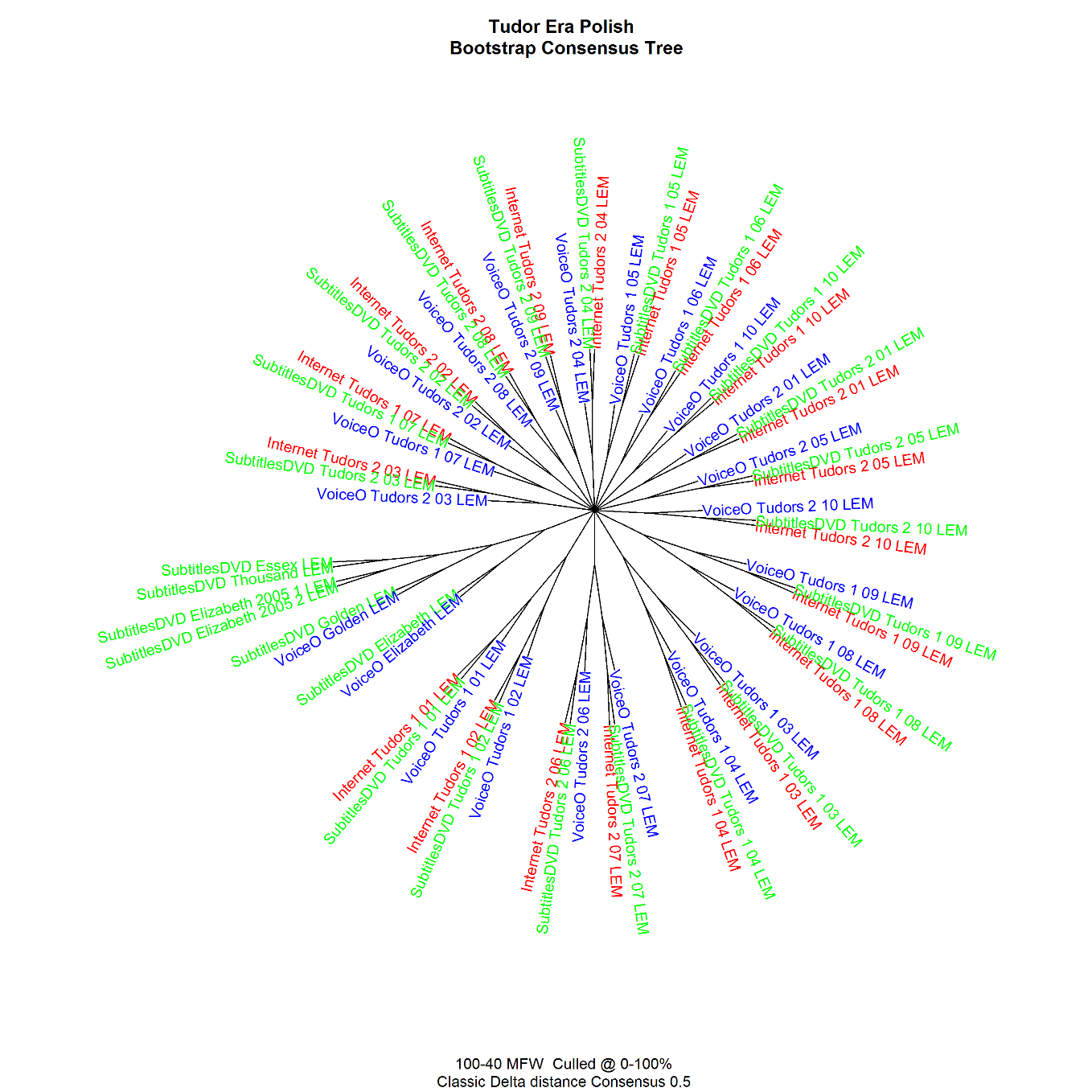

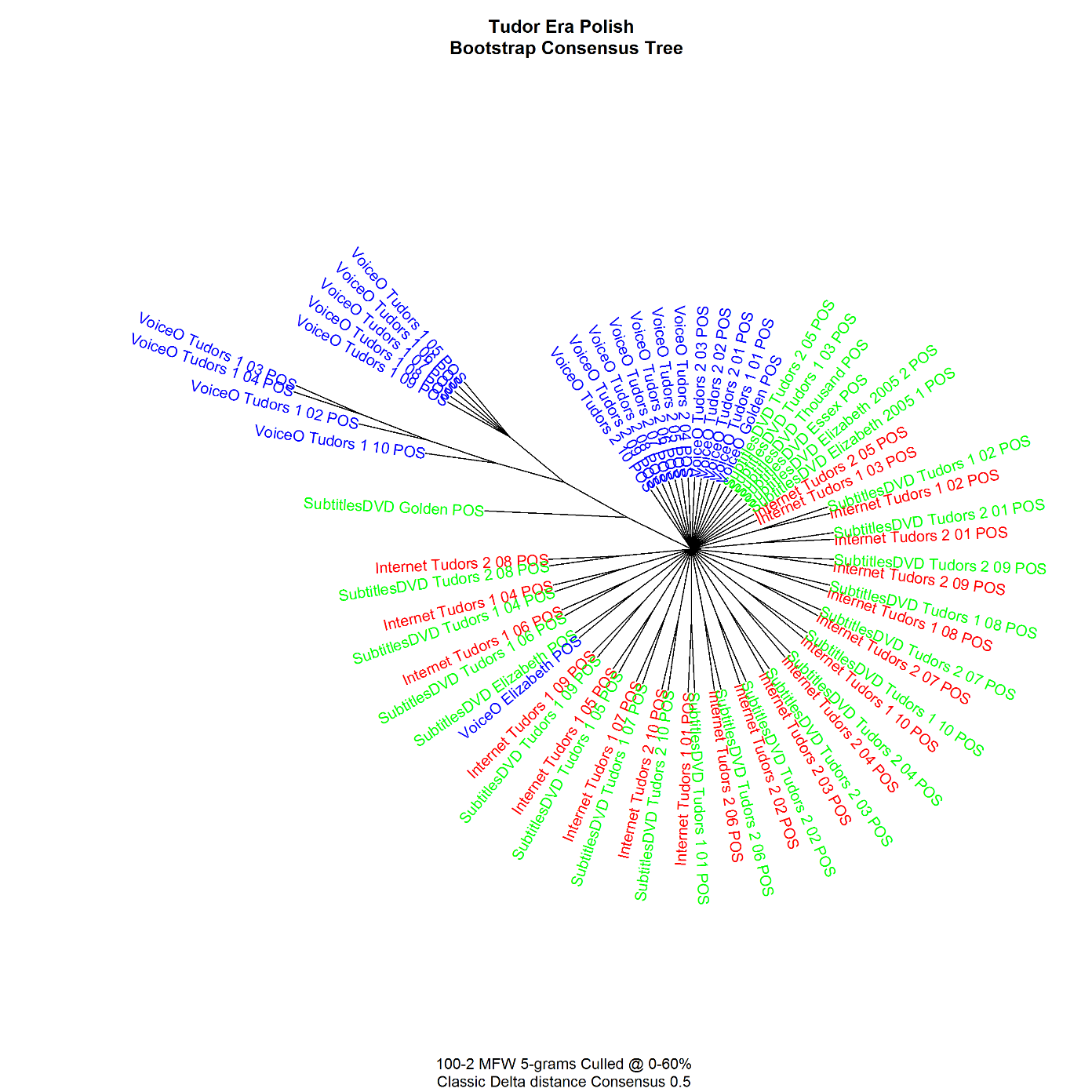

As concerns audiovisual translations, we arrived at rather unexpected conclusions. We compared versions of individual episodes of TV series and films in Italian (dubbing, subtitles) and Polish (voice-over, subtitles) by analyzing frequencies of single words and part-of-speech 5-grams; the latter measure was a rough approximation of syntax (Górski et al., 2014). As far as Italy is concerned, we noticed an astounding uniformity of style regardless of technique, be it subtitles or dubbing: translations of individual episodes of TV series and films clustered together in analyses of both word and part-of-speech frequencies. By contrast, Polish subtitles and voice-over scripts of the same episodes clustered together for single-word frequencies, while the latter formed their own clusters in part-of-speech 5-gram analysis. This is shown in Fig. 2 and 3.

Obviously, the similarities between dubbing and subtitles in Italian may stem from the fact that the latter are based on the former. However, the fact that even amateur subtitles, which usually are published before the release of the dubbed version, show a considerable affinity to dubbing, demonstrates high normalization of the formal language used in Italian historical films and television series.

All these results confirm our preliminary hypothesis that film genre influences the strategies of creating film dialogues and their translations. Although we believe that stylometric and computational analysis should not be the end in itself, it seems invaluable in audiovisual translation studies, encouraging closer qualitative analysis of the original and translated scripts. It invites further investigation of such issues as:

- the importance of cultural norms and conventions in film translation;

- significant intercultural differences in translation strategies used by subtitlers;

- complex relations between dubbing and subtitles, official and amateur subtitles, voice-over and subtitles

- cultural development of written / spoken language in a given country and the salient stylistic trends in audiovisual translation.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of project 2013/11/B/HS2/02890, supported by Poland’s National Science Center.

- Baños, R., Bruti, S. and Zanotti, S. (eds). (2013). Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. Special Issue: Corpus Linguistics and Audiovisual Translation: In Search of an Integrated Approach. 21(4).

- Bastian M., Heymann S. and Jacomy M. (2009). Gephi: an Open Source Software for Exploring and

- Manipulating Networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

- Burrows, J. (1987). Computation into Criticism: A Study of Jane Austen’s Novels and an Experiment in Method. Oxford: Oxford U. Press.

- Burrows, J. (2002). Delta: A measure of stylistic difference and a guide to likely authorship. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 17: 267-87.

- Craig, H., and Kinney, A. eds. (2009). Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship. Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press.

- Eder, M. (2015). Visualization in Stylometry: Cluster Analysis Using Networks. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30, first published online 3 December 2015, doi: 10.1093/llc/fqv061.

- Eder, M., Kestemont, M. and Rybicki, J. (2013). Stylometry with R: a Suite of Tools, in Digital Humanities 2013: Conference abstracts, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, pp. 487-89.

- Górski, R., Eder, M. and Rybicki, J. (2014). Stylistic fingerprints, POS tags and inflected languages: a case study in Polish, in Qualico 2014: Book of Abstracts. Olomouc: Palacky University, pp. 51–53.

- Freddi M, and Pavesi, M. (2009). The Pavia Corpus of Film Dialogue: Methodology and Research Rationale; in Freddi, M. and Pavesi M. (eds). Analyzing Audiovisual Dialogue: Linguistic and Translational Insights, Bologna: Clueb, pp. 95-100.

- Hoover, D. (2012). The Rarer They Are, the More There Are, the Less They Matter. Digital Humanities 2012: Conference abstracts, University of Hamburg. Hamburg U. Press, pp. 218-221.

- Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S. and Bastian, M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software. PLoS ONE, 9(6): e98679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098679.

- Jaeckle, J. (ed.). (2013). Film Dialogue. London & New York: Wallflower Press.

- Jockers, M. (2013). Macroanalysis. Digital Methods and Literary History. Champaign: U. of Illinois Press.

- Kozloff, S. (2000). Overhearing Film Dialogue. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Pérez-González, L. (2014). Audiovisual Translation Theories, Methods and Issues. London and New York: Routledge.

- R Core Team (2014). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Wien, http://www.R-project.org/.

- Rybicki, J. (2006). Burrowing into Translation: Character Idiolects in Henryk Sienkiewicz's Trilogy and its Two English Translations. Literary and Linguistic Computing 21(1), 91-103.

- Rybicki, J. (2007). Twelve Hamlets: A Stylometric Analysis of Major Characters' Idiolects in Three English Versions and Nine Translations, in Digital Humanities 2007: Conference Abstracts, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, p. 191.

- Rybicki, J. (2008). Does Size Matter? A Re-examination of a Time-proven Method, in Digital Humanities 2008: Conference abstracts, University of Oulu, p. 184.

- Schöch, C. (2013). Fine-Tuning our Stylometric Tools: Investigating Authorship and Genre in French Classical Drama, in Digital Humanities Conference 2013, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

- Schöch, C. (2014). Corneille, Molière et les autres. Stilometrische Analysen zu Autorschaft und Gattungszugehörigkeit im französischen Theater der Klassik, in Schöch, C. and Schneider, L. (eds). Literaturwissenschaft im digitalen Medienwandel, Mainz/Berlin: Philologie im Netz, pp. 130-57.

- Valentini, C. (2006). A Multimedia Database for the Training of Audiovisual Translators. JoSTrans: The Journal of Specialised Translation 6. http://www.jostrans.org/issue06/art_valentini.php.

- Valentini, C. (2008). Forlixt1: The Forli Corpus of Screen Translation: Exploring Macrostructures; in Chiaro, D. Heiss, Ch. And Bucaria, Ch. (eds). Between Text and Image. Updating Research in Screen Translation. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 37-51.

- Vickers, B. (2011). Shakespeare and Authorship Studies in the Twenty-First Century. Shakespeare Quarterly 62: 106-42.