Authors: Marilena Daquino, Silvio Peroni, Francesca Tomasi, Fabio Vitali

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: ontologies, linked open data, authoritativeness, provenance

The Project Zeri Photo Archive: Towards a Model for Defining Authoritative Authorship Attributions

1. Introduction

The global project of data conversion of the notable Italian ‘Zeri Photo Archive’ into a Linked and Open Dataset 1 primarily regarded the analysis of the description model of the available records, so as to define a collection of suitable ontologies to describe such a complex domain.

Indeed, the uniqueness of the Zeri collection 2, which includes about 290,000 photographs of works of art and monuments, lies in the rich documentation of the described artefacts, mostly related to provenance, attributions, restoration events and their connections to the collection of 46,000 books and 37,000 auction catalogues (Mambelli, 2014).

The full project entails, together with the ontological modeling, the production of the RDF dataset, the creation of proper links to the LOD cloud, and the definition of the user interface for browsing the dataset.

2. F Entry Ontology

The first activity of the project had been the formalization of the Scheda F (‘Fotografia’) (Mibact, 1999) , – the metadata standard of the Italian Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione (ICCD) – by mapping the schema onto CIDOC-CRM model (Crofts et al., 2011). In the conversion we initially considered the specific flavor of the Scheda F used by the Zeri Foundation, i.e. its subset of 113 fields (based on the experimental 1.04 version of the ICCD standard) and an handful of custom extensions to it. A deep analysis of the schema of the Scheda F showed that it is organized in semantically independent sections (called “paragrafi”, or paragraphs), each one belonging to a specific FRBR concept (Work, Manifestation, Item); this allows the mapping to proceed by logical sections affecting only a limited number of entities and relating these entities to the data documented by the fields of the schema.

Before accomplishing the mapping, we proceeded with the creation of a new ontology called FEO (F Entry Ontology 3). Since our final goal was to make available Scheda F data in a triple store, the target language we chose was OWL 2 DL. The current version of FEO introduces the classes and properties that characterize three specific concepts: the photograph, the work of art that is the subject of the photograph, and the Scheda F itself describing the photograph and its subject.

So, through the use of well-known ontologies – i.e. CIDOC-CRM, but also PROV-O (Lebo et al., 2013), and FaBiO (Peroni and Shotton, 2012), as part of the SPAR Ontologies 4 (Peroni, 2014) – plus the FEO ontology developed ad hoc, most of the content expressed as descriptive entries in the Scheda F have been already formally represented (Gonano et al., 2014).

3. OA Entry Ontology

In this presentation we propose an extension of our work on the Zeri Photo Archive by introducing a new ontology for representing works of art and their related information, namely, the OA Entry Ontology 5. In particular, this ontology is based on the Scheda OA (‘Opera d’Arte’) – another ICCD metadata standard 6 – and proposes a mapping between the content standard and, again, the CIDOC-CRM, in order to create shareable descriptions of metadata 7. In addition, other kinds of information that are not easily representable through the aforementioned standards, such as certain peculiar relations between works of art, are modelled by means of new classes and properties created in the OA Entry Ontology. This last allows to describe, in particular, the work of art and the related items, by focusing on some classes (e.g. copy, derivation, fake, drawing, model, replica, sinopia) and by using properties as necessary connection typization (e.g. conceived or former).

4. HICO and authorship attribution

Moreover, in this paper we further investigate a way for providing a clear and shareable representation of questionable information, i.e., the authorship attribution of works of art. In the Zeri Photo Archive there are particular authorship attribution created by either the Zeri Foundation cataloguers and/or by Federico Zeri (collector of photographs) himself, and such attributions (that could be accepted or discarded at certain point) are accompanied with the criteria that corroborate the cataloguers’ choice.

In order to provide a precise characterisation of all these aspects, we discuss the adoption of HiCO, Historical Context Ontology (Daquino and Tomasi, 2015) as a way for enabling a definition of authoritative attributions based on Zeri cataloguers’ own criteria. HiCO 8 is an OWL 2 DL ontology we created for describing contents of data (e.g., an authorship attribution), in particular cultural heritage data, and data creation itself (e.g., RDF statements representing above mentioned authorship attribution) as part of an interpretative process. Cultural heritage object is a wide concept: it includes any sort of representation of culture heritage embodied in a tangible form like artifacts (books, documents, and, as in this case, works of art), but also any concept, assertion and interpretation somehow bounded to cultural objects.

With the hico:InterpretationAct class it’s possible to describe the interpretation act as a process:

- the conceptualization of the interpretation and its classification, for enabling further relations among different kind of interpretations;

- the embodiment of the interpretation as RDF statements, for representing information extracted from the content of the object of interest.

Two fundamental object properties complete the process: the hico:hasInterpretationType property and the hico:hasInterpretationCriterion property. The former states an arbitrary classification of the interpretation, which can be simply defined as philological, historical, semiotic, linguistic etc. The latter is a briefly explanation of the criterion used to state information extracted from a source, e.g. a literally transcription, a hypothesis, or the adoption of the literature about a specific argument.

A crucial aspect of the project is the correct formalization of statements so as to allow the ontologically-consistent coexistence of data created by different actors that express contradictory statements about the same subject (e.g., authorship attribution data of a work of art), in order to guarantee the data integration with Pharos (Reist et al., 2015) project partners, of which the Zeri Foundation is a member. By the use of SWRL rules applied to relations between sources, criteria and context information used by an agent to explain his interpretation, we could formally infer when an interpretation can be considered authoritative.

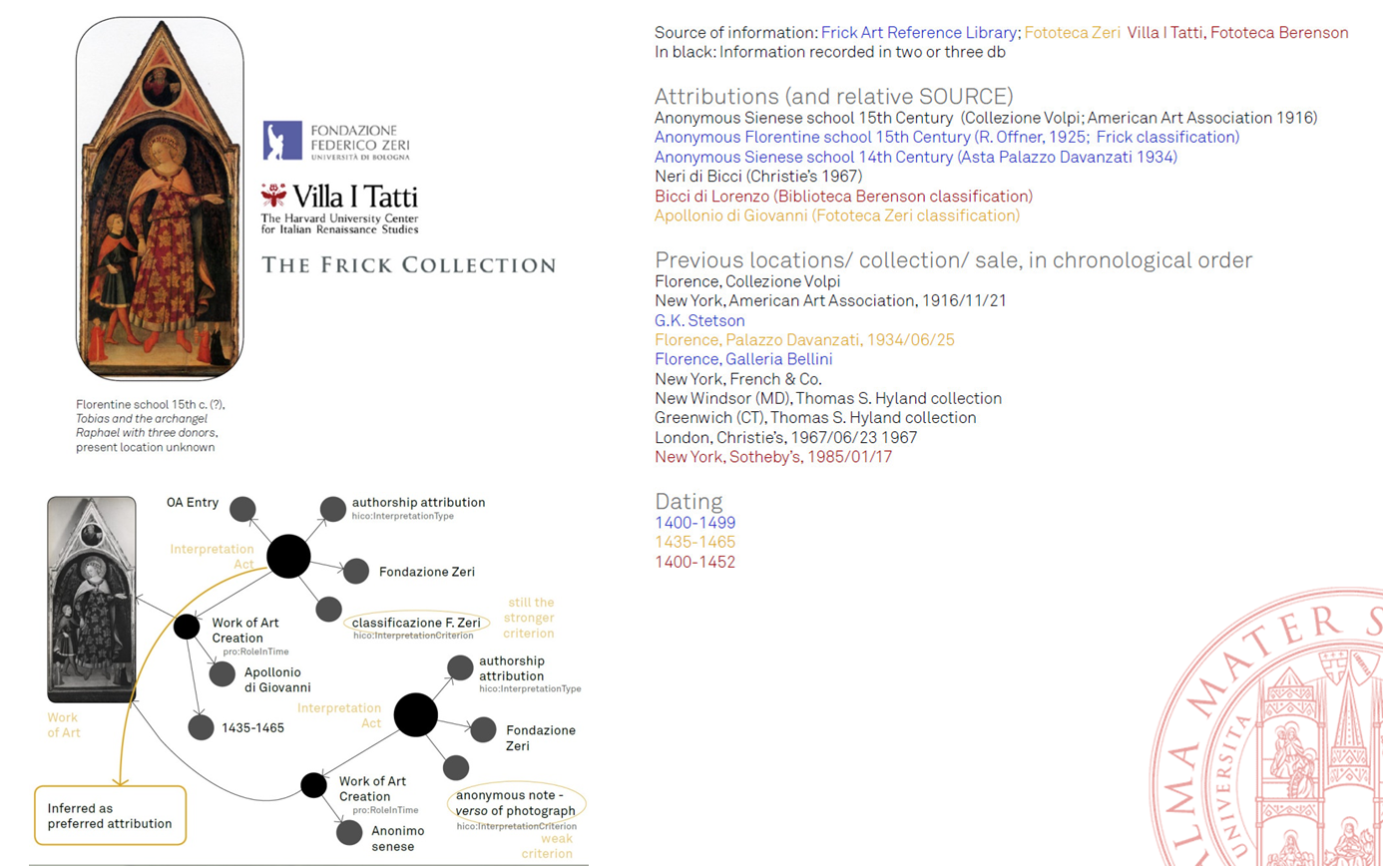

5. An example of authoritative assertion

We could give an example. We state aside the interpretation (i.e. the assertion “An artist X is author of a specific work of art Y in a specific time Z”) which sort of interpretation we are dealing with (i.e. authorship attribution), and which criteria have been used by the cataloguer to assert such proposition. A provenance statement ensures both author of assertion (i.e. interpretation) and author of data conversion are fully described, ensuring that no contradictory statements will affect data validity.

When necessary conditions for stating authorship are fulfilled, an attribution may be inferred as authoritative. In the example (Fig. 1), we have an attribution which respects minimal requirements for being considered an authoritative assertion:

- it has been stated by a well-known author (i.e. the cataloguer of Zeri Foundation);

- it considers as criterium an authoritative source (i.e. the photo depicting the work of art);

- it agrees with another interpretation, i.e. Federico Zeri classification.

This obviously doesn’t entail that the attribution is surely correct, but it can be a useful tool for historians when searching for different attributions and related criteria adopted in interpretative process.

6. Conclusions

To conclude, as said before it will be the natural completion of the Zeri Project the RDF triple store set up, the creation of links to other datasets, and the definition of the user interface for browsing the linked open dataset. All these activities are now object of our research group industry and the final publication of the project is expected for the middle of 2016. Data had already been transformed in a RDF/XML dataset, according to above mentioned ontologies. Next steps of the project involve thus data publication, ensuring access to them through a SPARQL endpoint. When published, data will be enriched with further RDF links to major datasets and authority files online (e.g. VIAF for people and works, Getty thesauri, GeoNames for places 9). This ensures our data will really be part of the LOD Cloud, avoiding creation of another data silo. So enriched data will then be exploited in a new smart application, which will enable users to search data about both photos and works of art. Through this modelization data and new relations will be easier discovered, enhancing user experience.

- MiBACT (1999). Strutturazione dei dati delle schede di catalogo: beni artistici e storici: scheda F, prima parte. Roma: ICCD.

- Mambelli, F. (2014). Una risorsa online per la storia dell’arte: il database della fototeca Zeri. In: Ciotti, F. (Ed.), Digital Humanities: progetti italiani ed esperienze di convergenza multidisciplinare. Quaderni Digilab, Università di Roma La Sapienza.

- Crofts, N., Doerr, M., Gill, T., Stead, S. and Stiff, M. (2011). Definition of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (version 5.0.4). http://www.cidoc-crm.org/docs/cidoc_crm_version_5.0.4.pdf.

- Lebo, T., Sahoo, S. and McGuinnes, D. (2013). PROV-O: the PROV Ontology. W3C Recommendation. http://www.w3.org/TR/prov-o/.

- Peroni, S. and Shotton, D. (2012). FaBiO and CiTO: ontologies for describing bibliographic resources and citations. Journal of Web Semantics: Science, Services and Agents on the World Wide Web, 17: 33-43.

- Peroni, S. (2014). The Semantic Publishing and Referencing Ontologies. In: Peroni, S., Semantic Web Technologies and Legal Scholarly Publishing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 121-93.

- Gonano, C.M., Mambelli, F., Peroni, S., Tomasi, F. and Vitali, F. (2014). Zeri e LODE. Extracting the Zeri photo archive to Linked Open Data: formalizing the conceptual model. Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/ACM Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL 2014). IEEE, pp 289-98.

- Daquino, M. and Tomasi, F. (2015). Historical Context (HiCo): a conceptual model for describing context information of cultural heritage objects. Communication in Computer and Information Science, Berlin: Springer Verlag, pp. 424-36.

- Reist, I., Farneth, D., Stein, R. and Weda, R. (2015). An Introduction to PHAROS: Aggregating Free Access to 31 Million Digitized Images and Counting. Speech at CIDOC 2015. New Dehli.

The project is supported by the Zeri Foundation with the University of Bologna and started in 2014

Fondazione Zeri, Photo Archive Catalog, http://catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it

See the ICCD cataloging standards at: http://www.iccd.beniculturali.it/index.php?it/473/standard-catalografici

We are planning to publish both the F and the OA mapping to CIDOC-CRM in the next few months, according with the ICCD activities

A first check on https://datahub.io/dataset