Authors: Fahad Khan, Francesca Frontini, Federico Boschetti, Monica Monachini

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: Liddell Scott, ancient Greek, Linked Open Data, lemon

Converting the Liddell Scott Greek-English Lexicon into Linked Open Data using lemon

1. Introduction

The emergence and growing popularity of Linked Open Data (LOD) offers researchers a new range of possibilities when it comes to publishing datasets online (Hyvönen 2012, Oomen et al 2012); indeed not only does the success of LOD greatly facilitate the process of making scholarly data accessible and to a wider community but it also permits the enrichment of individual datasets by linking them to the other datasets available on the so called Linked Open Data Cloud. The advantages of Linked Open Data for teachers, academics and students in the humanities are obvious and are indeed manifold. However there is currently a paucity of linked open datasets in fields such as philology and literary studies, and in particular of datasets that deal with classical languages such as ancient Greek, Sanskrit, and Latin. This seems strange given the rich abundance of surviving works, of both a religious and secular character, that exist in those languages. A salient consideration here relates to the fact that even when such works have been digitised and made available in a format such as TEI-XML, a format which renders the structure and content of such texts more amenable to computer processing, the conversion of these resources into the Resource Data Framework (RDF), the standardised data model that underpins the Semantic Web, is not always straightforward.

In this article we describe ongoing work in the conversion of an important 19th century Ancient Greek resource the Liddell-Scott-Jones Lexicon, into RDF, part of a wider program of work that has been recently initiated at CNR-ILC in converting historical lexicons in languages such as Greek, Latin and Arabic into Linked Open Data.

2. Background

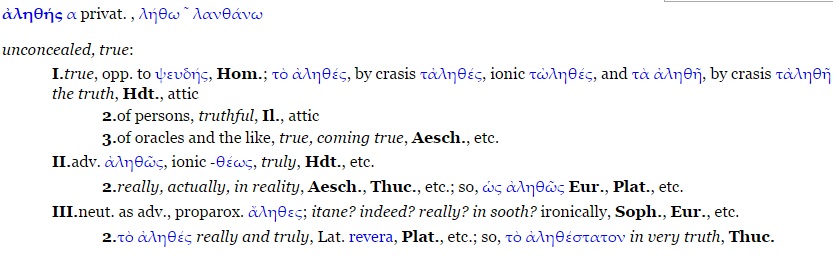

The Liddell-Scott-Jones lexicon (LSJ), or to give it its original title “A Greek-English lexicon”, is a bilingual ancient Greek-English dictionary which since its first edition was published in the mid-nineteenth century has come to be regarded as amongst the most authoritative of modern day lexicographic resources dealing with the ancient Greek language, indeed it has the reputation of a standard in the field. As a result of its popularity the LSJ has been made available in a number of different versions differing in terms of the number of entries and the amount of data which they contain. For the work described in this paper we are using an abridged version of the LSJ which was originally published as “An Intermediate Greek-English lexicon,” but which is more colloquially known as the “Middle Liddell” (ML). Fig. 1 shows the lexical entry for the adjective ἀληθής (alēthēs) in the ML. Entries in the ML are structured into different nested (sub-)senses, and each of these senses contain references (usually just the name of an author) attesting the use of the word as described in the sense’s gloss.

There were a number of motivations for choosing the LSJ as a starting point of our work into converting legacy lexical resources into linked data: aside of course from the question of its historical importance and continuing influence in the field of philology. Firstly we felt that given the lack of ancient Greek lexical resources in linked open data -- at the time of writing the Linguistic Linked Open Data cloud (Chiarcos et al 2011), that part of the LOD cloud that deals with linguistic data, contains no ancient Greek datasets -- there was an obvious necessity to ensure a presence on the cloud for a language that is absolutely foundational to the history of Western civilisation. Additionally there was also the challenge of converting a legacy resource like the LSJ which in its published form, and even in an abridged version like the ML, manages to condense a significant amount of lexical information in a relatively short amount of text, into linked data. In order to represent this information in the RDF model, and to stay close to the spirit of the Linked Open Data movement, a lot of what was implicit in the original text had to be teased out and rendered explicit.

Finally, one very important practical reason for choosing the ML was the fact that the conversion of the ML into XML using the TEI dictionary guidelines had already been carried out and made freely available under a creative commons license by the Perseus project (Crane et al 2013). This obviously saved us the trouble of digitizing the text ourselves and meant that we could work from a source file that was already annotated for lexical entries, senses, translations, etc.

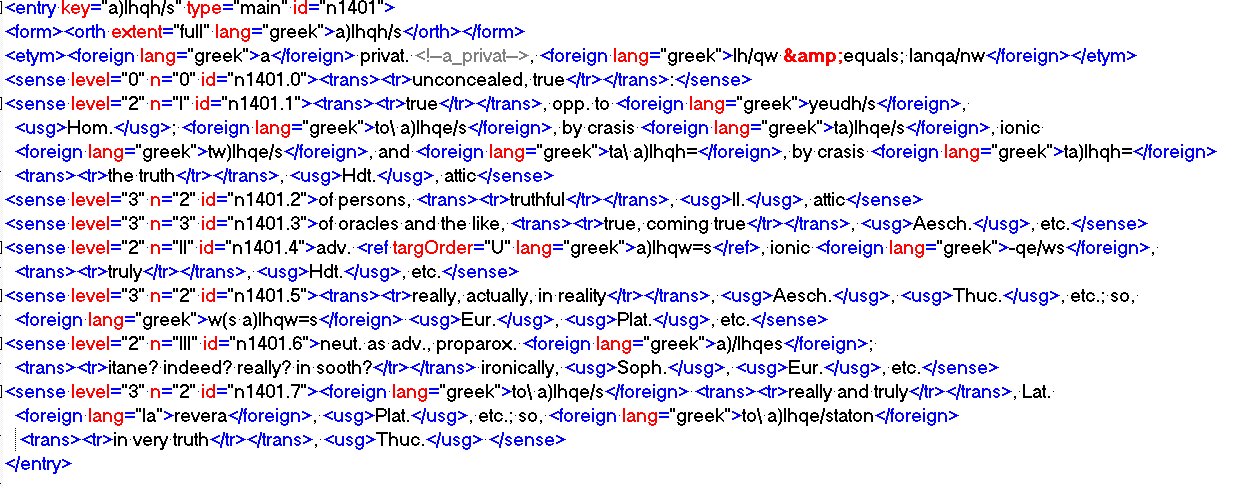

In Fig 2 below we present the TEI-XML encoding of the ML entry for ἀληθής from the Perseus XML version of the ML which we used as our source dataset.

The TEI-XML encoding for each entry already contains most of the information which we wish to represent in RDF marked up, and so the actual processing of the dataset was fairly straightforward. The part of the conversion which, however, did call for some thought was the use of the lemon model to structure the RDF translation.

3. Translating the Middle Liddell in RDF using lemon

4.

For the conversion of the TEI-XML version of the ML we decided to use the lemon model for publishing lexicons in RDF (McCrae et al 2011, McCrae et al 2012). lemon has by now become a de facto standard for converting lexicographic resources into RDF and has been used to convert a number of important lexical resources such as Wordnet (McCrae 2014), UBY (Eckle-Kohler et al 2014), Wiktionary (McCrae et al 2012), and Parole/Simple/Clips (Del Gratta et al 2015). The Linked Open Data movement emphasises the re-use of general vocabularies and models in order to ensure semantic interoperability between datasets. And so given the widespread use of lemon in converting lexical resources into RDF, and given the lack of a more specific alternative specifically tailored for lexicographic resources like the ML, we decided to use it as the framework for our conversion. However using lemon for the conversion has not been without its challenges. One of the primary difficulties rests in the fact that lemon was originally intended as an onomasiological model, that it is, it was designed with the perspective in mind of enriching an already existing ontological or conceptual resource with linguistic information (Cimiano et al 2013). However in our case we started out with a very rich lexical resource but without any particular pre-ordained ontological or conceptual datasets in mind to which to link it. In fact we are not currently using the lemon:reference relation to link our dataset to others.

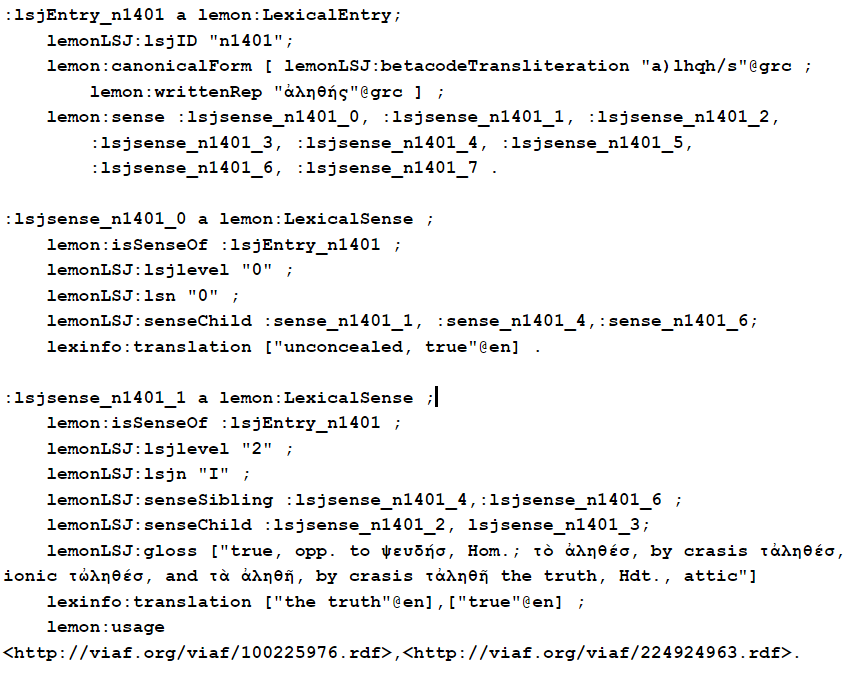

The ML in particular and the LSJ more generally represent lexical resources that have a specific and relatively complex way of encoding information and that contain a lot of philological and historical data alongside or in addition to “pure” semantic information. Therefore in in order to ensure a faithful translation we had to define a number of new classes and relations in addition to those in lemon. In what follows below we will briefly describe (most of) the additional classes and properties which were introduced in order to model the ML and which together make up the lemonLSJ module. Fig. 3 below is a diagram showing classes and properties in the lemonLSJ module and their relation to some of the main classes.

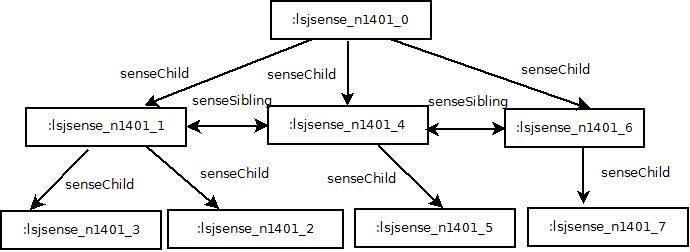

The new class lemonLSJ:Gloss represents the written text associated with each sense; the object relation lemonLSJ:gloss then links elements of this class to lemon senses. The lemonLSJ:usage relation links a sense to an ontological resource describing where that sense was used, e.g., by linking to an author or work where that sense can be found.1 We have also added the relations lemonLSJ:senseChild, and lemonLSJ:senseSibling in order to represent the nesting of subsenses in ML entries.

In Fig 4 we present an excerpt of the lemonLSJ RDF-Turtle encoding of the ML entry for ἀληθής with only two of the attached senses represented. Note that we have linked the second of the word senses in Fig 4 to instances in the VIAF dataset (in this case the entries for Herodotus and Homer).

The diagram in Fig. 5 shows how the nesting of senses is treated in the RDF encoding.

5. Conclusions and future work

In this paper we have briefly described ongoing work in the conversion of an ancient Greek-English lexicon into RDF. Currently we are manually checking the RDF triples resulting from our conversion scripts and we also plan to additionally link the senses to Princeton Wordnet synsets by checking similarity of the glosses to synset glosses. The resulting dataset will soon be made available as an RDF dump together with other lexical resources of ILC CNR.

6. Acknowledgments

First of all we would like to thank Perseus project for converting the data and for making it freely available. Thanks also to the organisers of the mylider 2015 Summer Datathon, during which some of this work was carried out, for their advice.

- Bennett, R., Hengel-Dittrich, C., O’Neill, E. T. and Tillett, B. B. (2006). Viaf (virtual international authority file): Linking die deutsche bibliothek and library of congress name authority files. World Library and Information Congress: 72nd IFLA General Conference and Council. Citeseer http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.150.5328&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 29 October 2015).

- Bizzoni, Y., Boschetti, F., Del Gratta, R., Diakoff, H., Monachini, M. and Crane, G. (2014). The Making of Ancient Greek WordNet. Proceedings of Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Iceland. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2014/pdf/1071_Paper.pdf (accessed 29 October 2015).

- Chiarcos, C., Hellmann, S. and Nordhoff, S. (2011). Towards a Linguistic Linked Open Data cloud: The Open Linguistics Working Group. TAL, 52(3): 245–75.

- Cimiano, P., McCrae, J., Buitelaar, P. and Montiel-Ponsoda, E. (2013). On the Role of Senses in the Ontology-Lexicon. In Oltramari, A., Vossen, P., Qin, L. and Hovy, E. (eds), New Trends of Research in Ontologies and Lexical Resources. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 43–62. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-31782-8_4 (accessed 31 October 2015).

- Crane, G., Almas, B., Babeu, A., Cerrato, L., Krohn, A., Baumgart, F., Berti, M., Franzini, G. and Stoyanova, S. (2014). Cataloging for a Billion Word Library of Greek and Latin. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Digital Access to Textual Cultural Heritage. (DATeCH ’14). New York, NY, USA: ACM, pp. 83–88. doi:10.1145/2595188.2595190. http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2595188.2595190 (accessed 29 October 2015).

- Del Gratta, R., Frontini, F., Khan, F. and Monachini, M. (2015). Converting the parole simple clips lexicon into rdf with lemon. Semantic Web Journal, 6(4): 387–92.

- Eckle-Kohler, J., McCrae, J. and Chiarcos, C. (2014). LemonUby-a large, interlinked, syntactically-rich resource for ontologies. Semantic Web Journal, Submitted. Special Issue on Multilingual Linked Open Data http://www.semantic-web-journal.net/system/files/swj404.pdf (accessed 29 October 2015).

- Elliott, T. and Gillies, S. (2009). Digital geography and classics. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 3(1).

- Francopoulo, G. (2013). LMF Lexical Markup Framework. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hyvönen, E. (2012). Publishing and Using Cultural Heritage Linked Data on the Semantic Web. Synthesis Lectures on the Semantic Web: Theory and Technology, 2(1): 1–159. doi:10.2200/S00452ED1V01Y201210WBE003.

- Janowicz, K. (2009). The Role of Place for the Spatial Referencing of Heritage Data. The Cultural Heritage of Historic European Cities and Public Participatory GIS Workshop.. The University of York, UK, pp. 17–18.

- Liddell, H. G. and Scott, R. (1896). An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon: Founded upon the Seventh Edition of Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon. Harper & Brothers.

- McCrae, J., Aguado-de-Cea, G., Buitelaar, P., Cimiano, P., Declerck, T., Gómez-Pérez, A., Gracia, J. et al. (2012a). Interchanging lexical resources on the Semantic Web. Language Resources and Evaluation, 46(4): 701–19.

- McCrae, J., Fellbaum, C. and Cimiano, P. (2014). Publishing and Linking WordNet using lemon and RDF. Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Linked Data in Linguistics. http://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/download/2732779/2732785 (accessed 29 October 2015).

- McCrae, J., Montiel-Ponsoda, E. and Cimiano, P. (2012b). Integrating WordNet and Wiktionary with lemon. Linked Data in Linguistics. Springer, pp. 25–34. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-28249-2_3 (accessed 29 October 2015).

- McCrae, J., Spohr, D. and Cimiano, P. (2011). Linking lexical resources and ontologies on the semantic web with lemon. The Semantic Web: Research and Applications. Springer, pp. 245–59. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-21034-1_17 (accessed 29 October 2015).

- Minozzi, S. (2009). The Latin Wordnet Project. http://www.dfll.univr.it/documenti/Iniziativa/dall/dall036637.pdf (accessed 29 October 2015).

- Oomen, J., Baltussen, L. B. and Erp, M. van (2012). Sharing cultural heritage the linked open data way: Why you should sign up. Museums and the Web.