Authors: Mohammad Hossein Haqiqat khah, Babak Nadjar Araabi

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: Spatio-Temporal Reasoning, Evidence Combination, Dempster-Shafer Theory of Evidence, Historical Reasoning

The Ibn Darraj Project: SpatioTemporal Reasoning Engine Based on Evidence Combination *

1. Introduction

In historical statements, we face narrations that are vague in sense of persons, places, times, and events. This means that we have uncertainties and non-specificities about the persons and the events, and the time and place the event has taken place. These uncertainties are mostly caused by ignorance about the characters and events assignments, and definition of the boundaries narrowing down the time and space frames. Moreover, we have narrations that usually do not uphold each other, and have different validities or certainties. Putting these contradictory narrations together to judge about the most definite event needs a great effort, and is a hard task for unaided human mind.

Although its importance and utility, there are not any noteworthy research on spatio-temporal reasoning to combine evidences, or applying evidence combination methods (such as Dempster-Shafer Theory of Evidence) in spatio-temporal reasoning. Hence, this paper delivers a novel tool to compensate this deficiency.

2. Methodology

To reach this goal, we divide the problem to three main domains, and simplify the question to minimize the efforts and implementation cost of each step.

2.1. Extracting and Structuring Evidences

In this step, we model narrations as narration trees, such as 'A' says he has heard 'B' talking about [Event]. Each of the narrators has a validity coefficient indicating the reliability of the narration made by the person. Then using the SRL (Semantic Role Labeling) methods (Gildea and Jurafsky, 2000), we structure the narrations to a standard form Jurafsky and Martin (2009). Hence, we have a bunch of narrations, and each of the narrations has a narration chain and a standard, structured event.

2.2. Finding Similar Events

In this step, using Natural Language Processing tools, we form [multiresolution] verb clusters that help us define the same events that have meanings in common. For example, killing, shooting down, hanging, and choking can be considered as different ways to end one’s life, and we may put them in one cluster. These clusters are extracted from WordNet (Hirst and St-Onge, 1998), and define the degree to which we may merge events based on their verbs (Meng et al., 2013).

2.3. Evidence Combination

The main role of the reasoning engine is to combine different evidences to calculate the probability of a hypothesis. To do so, one can use the very familiar Bayesian inference method to incorporate different evidences using the Bayes theorem. However, this modeling cannot deal with non- specificities. For instance, if we have four persons A, B, C, and D as candidates of an assassination, we may assign probabilities to Assassins = {A,B,C,D} or other probabilities to subsets of the Assassins set. However, if we do not have crisp evidences defining the probabilities of each member we are unable to do inference where the subsets overlap. As a result, we cannot use the Bayes rule to combine evidences of Pr(A or B or C) and Pr(B or C or D) if we do not know Pr(B or C)or assume some other hypothesis for it.

On the other hand, there is a great advantage in using the Dempster-Shafer Theory of Evidence (DST) compared to the classical probabilistic reasoning based on the Bayesian Theory (BT). By DST, it’s possible to take non-specificity into account as well as randomness, which was not possible in BT. In many problems, such as reasoning based on non-specific statements (which are modeled here as narrations), accumulated non-specificity (vagueness) may reveal more specific details. This is the main reason to use DST instead of BT.

It means that when each narration determines a non-specific time and place for an event, or these space-time pieces overlap each other, we are able to define precisely the most and least probabilities that the event has taken place in a specific portions of space-time. These probabilities are usually mentioned as lower and upper bounds of probability, and may be interpreted as Belief and Plausibility respectively (Zadeh, 1986).

3. Tools and Methods

The core element of the system is a reasoning engine that combines different pieces of evidence. The output will be total expected probabilities and the upper and lower bound of probabilities for different pieces of space-time. This task can be accomplished by efficiently succeeding in the following:

- Modelling space and time effectively, and

- Using the evidence combination methods to deliver the reasoning engine, mainly using Dempster-Shafer Theorem.

We used the CRMgeo model (Doerr and Hiebel 2013) that is standardized in ISO 21127:2014 as the space-time model. We have incorporated GIS tools (as done in Hirschfield and Bowers, 2001; and Fuhrmann et al., 2013) and standard ISO 8601:2004 to model space and time respectively. However, due to the rich and flexible ontology design of the CRMgeo model (Doerr and Hiebel, 2013) which is standardized in ISO 21127:2014, we switched to it as our main space-time model. We also benefited from the CRMinf argumentation model (Doerr 2015) to model the narrations.

At last, we implemented different evidence combination rules in R language to combine the structured narrations together, resulting in and reduced ambiguity and vagueness (Kohlas and Monney n.d., Barnett 1991)

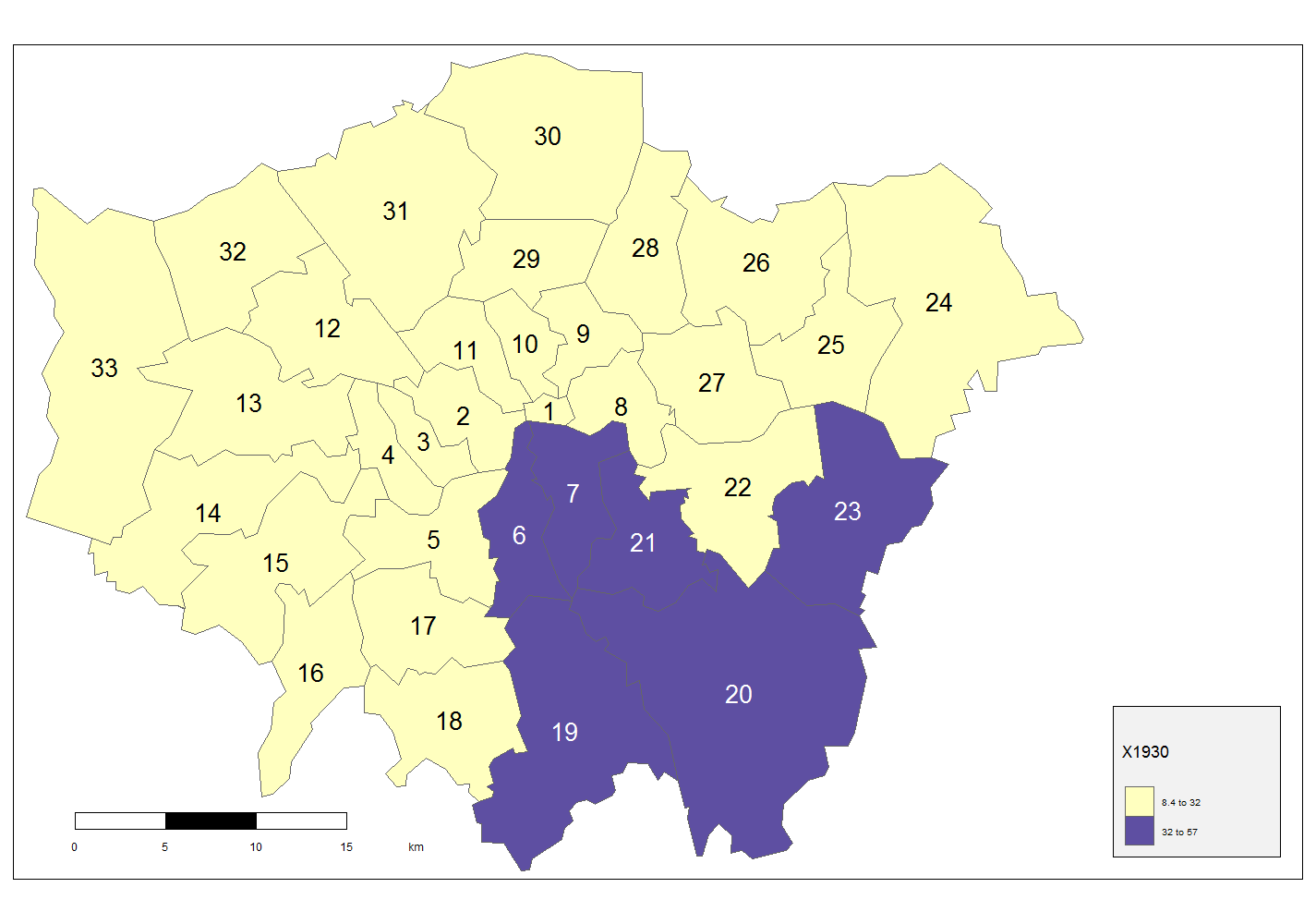

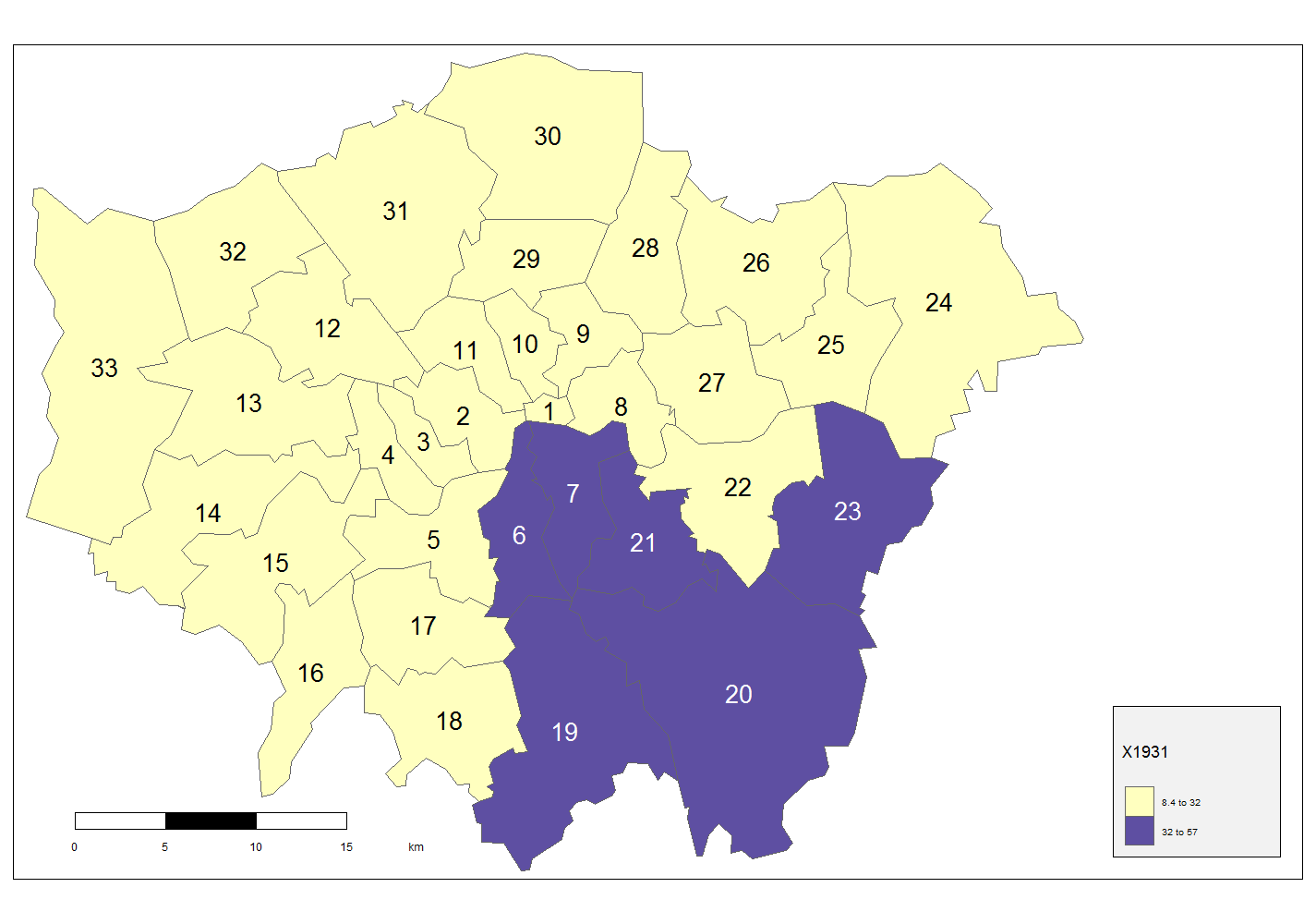

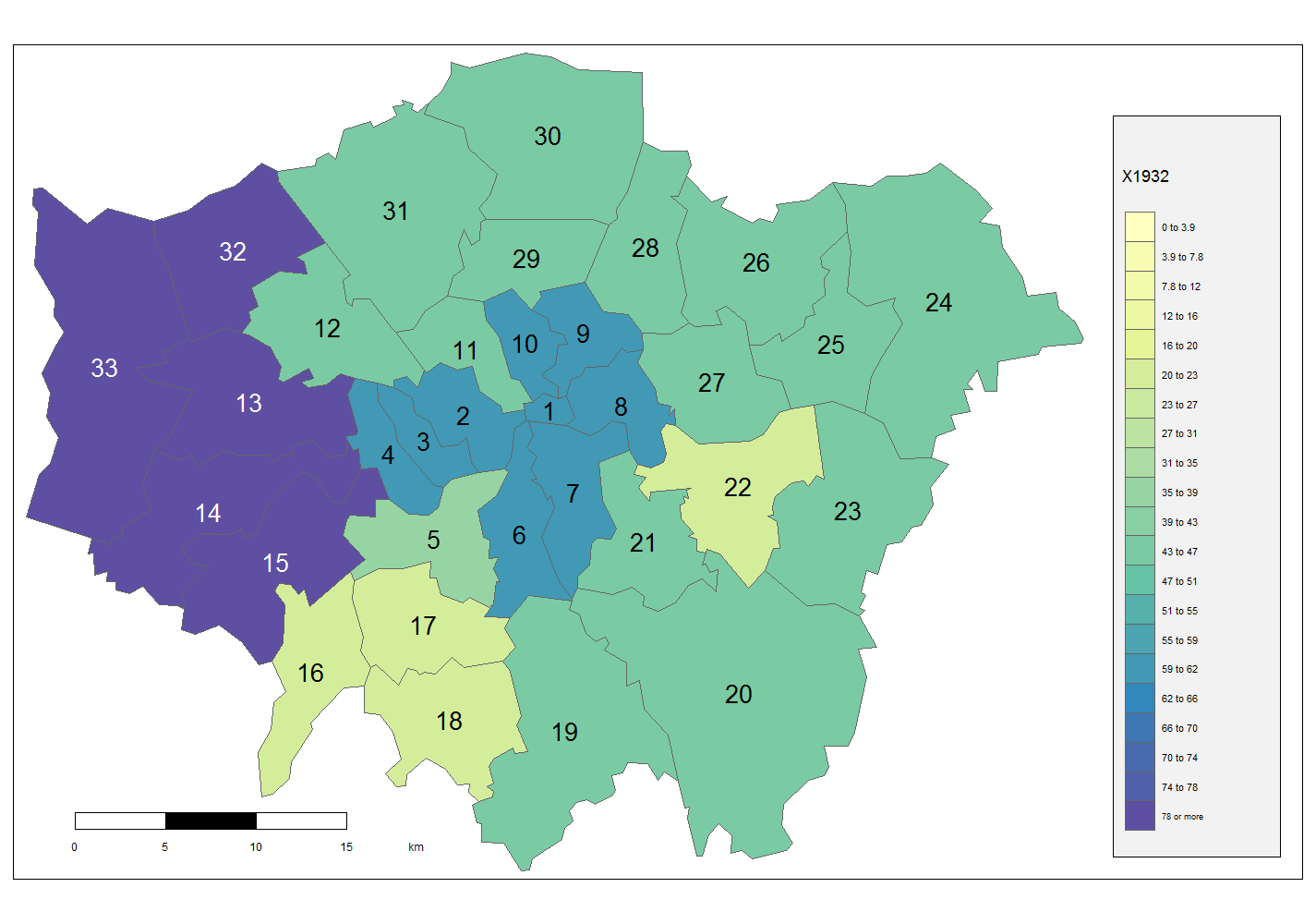

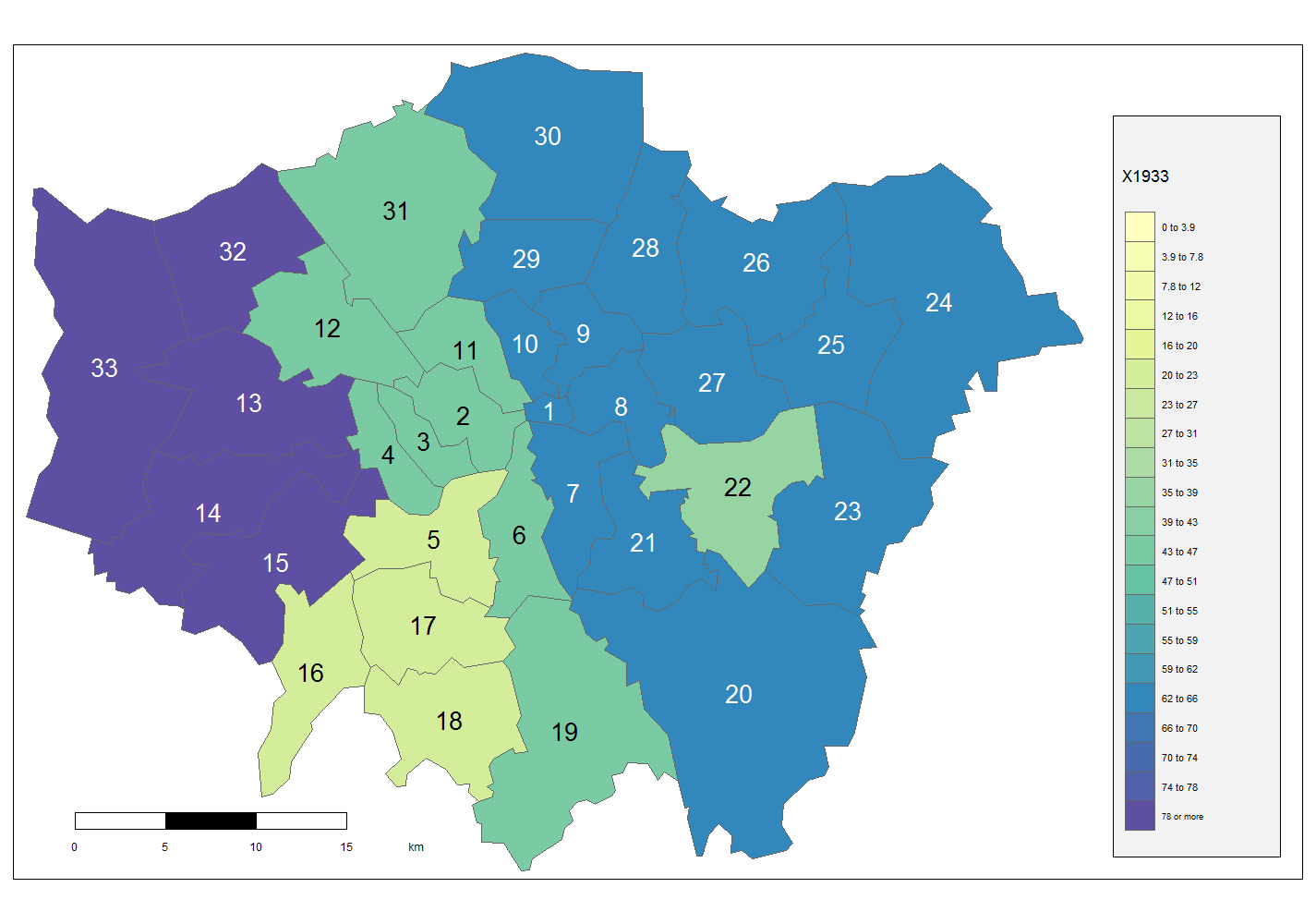

4. An Example of a Toy Problem

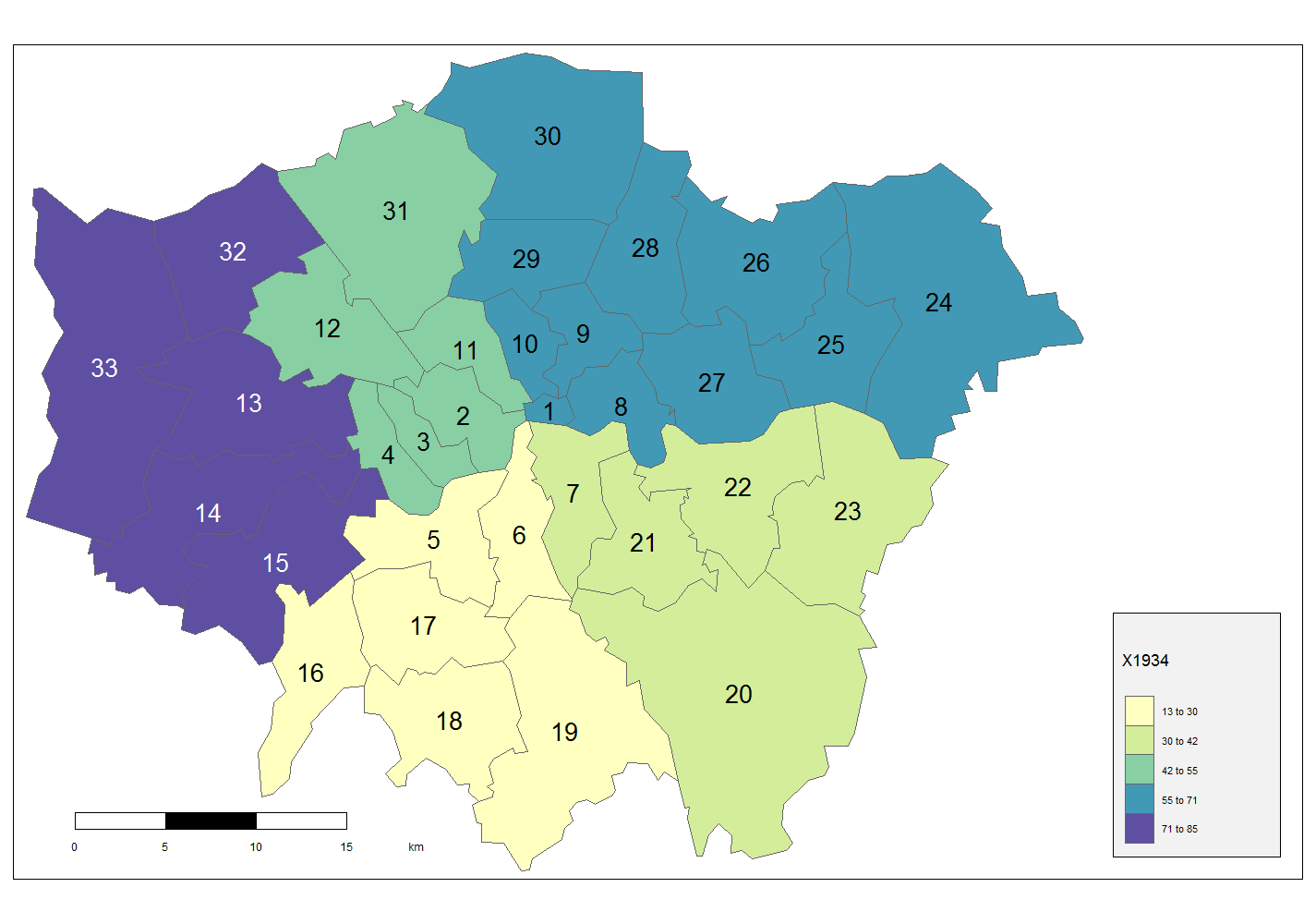

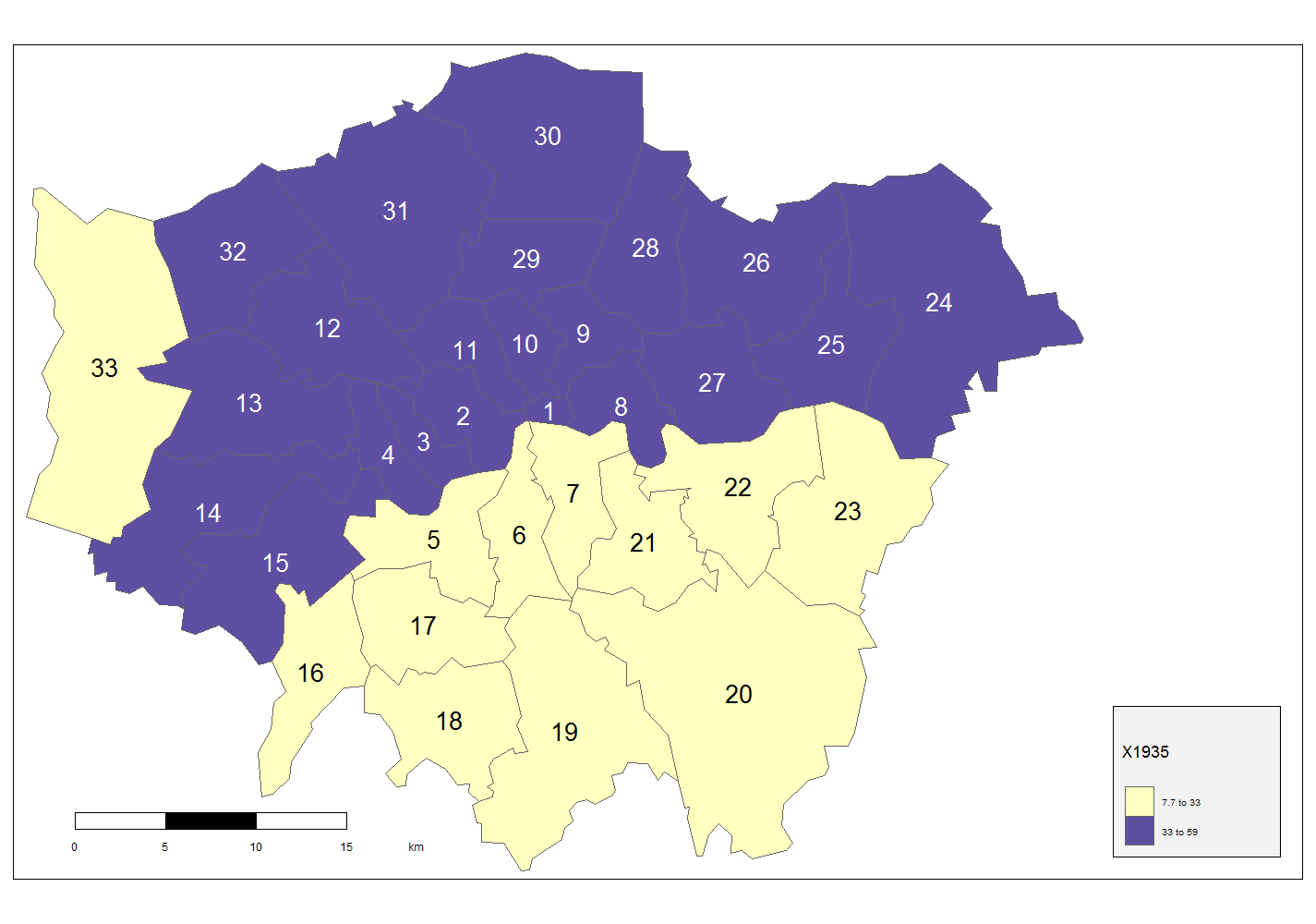

The following figures are the output results of a reasoning over a toy problem of an airplane crash in different boroughs of London, and is plotted for each of the years in the 1930-1935 timeframe. Each plot is for a specific time (e.g. X1930 is for the year 1930). The values of the average probability of the crash in each borough are represented in decibels to better visualize the slight changes of probability in similar regions.

The problem is to combine the following five narrations to gether. The numbers in the parentheses are the validities and/or confidence of the statements.

1. I think (70%) it was between 1930-33 that a plane crashed in the south east of London

2. If I'm correct (90%) I heard my brother that he's somehow sure (80%) that it was between 1932-35 that the Air Union cargo plane hit the northern bank of the Thames river.

3. I cannot remember it clearly (60%) but in 1933 or 34 an airplane of a post company hit the eastern London.

4. It's hard to remember (60%), but my father once told me (90%) that he witnessed an airplane crash in the center of London, Old London.

5. If I'm remembering correctly (80%), an airplane crashed the west London between the 1932-34.

5. About the Project Name

Nuh (Noah) ibn Darraj al-Nakha‘ı¯ (d. 182 AH/ AD 798), was the Shı‘ite judge of Kufa, and later in his life, the grand judge of the eastern half of Baghdad. Nuh’s older brother, Jamil ibn Darraj al-Nakha‘ı¯ was a prominent Shı‘ite jurist in the latter part of the second Islamic century (AD 760s - 810s) (Modarressi, 2003)

- Barnett, J. A. (1991). Calculating Dempster-Shafer plausibility. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 13(6): 599–602.

- Doerr, M. (2015). CRMinf: the Argumentation Model.

- Doerr, M. and Hiebel, G. (2013). CRMgeo : Linking the CIDOC CRM to GeoSPARQL through a Spatiotemporal Refinement, pp. 1–40.

- Fuhrmann, S., Huynh, N. T. and Scholz, R. (2013). Crime Modeling and Mapping Using Geospatial Technologies, Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-94-007-4997-9.

- Gildea, D. and Jurafsky, D. (2000). Automatic labeling of semantic roles. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics - ACL ’00, (1972), pp.12–520. Available at: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1075218.1075283.

- Hirschfield, A. and Bowers, K., (2001). Mapping and analysing crime data, London: Taylor and Francis, 2001. Available at: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1329199/.

- Hirst, G. and St-Onge, D. (1998). Lexical chains as representations of context for the detection and correction of malapropisms. WordNet - An Electronic Lexical Database, pp.305–32. Available at: http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/wordnet.

- Jurafsky, D. and Martin, J. H. (2014). Speech and language processing. Pearson.

- Kohlas, J. and Monney, P. A. (2013). A mathematical theory of hints: An approach to the Dempster-Shafer theory of evidence, 425, Springer Science and Business Media.

- Meng, L., Huang, R. and Gu, J. (2013). A Review of Semantic Similarity Measures in WordNet. International Journal of Hybrid Information Technology, 6(1): 1–12.

- Modarressi, H. (2003). Tradition and Survival: A Bibliographical Survey of Early Shi’ite Literature, 1.

- Zadeh, L. A. (1986). Simple View of the Dempster-Shafer Theory of Evidence and Its Implication for the Rule of Combination. AI Magazine, 7(2): 85–90. Available at: http://www.aaai.org/ojs/index.php/aimagazine/article/view/542.