Authors: Adam Tomasz Pawłowski

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: ChronoPress, corpus, 1945–1954, historical linguistics, Polish

Chronological corpora: Challenges and opportunities of sequential analysis. The example of ChronoPress corpus of Polish

1. Chronological corpus – definition

The notion of chronological corpus has appeared so far only in publications of limited circulation (cf. Pawłowski, 2006), whereas it is practically absent from mainstream literature on corpus linguistics and digital humanities. This is somewhat surprising given that the research of so called “lexical series” has been conducted in the past (cf. Brunet, 1981; Salem, 1987) and that Google has been for some years developing the tools Ngram Viewer and Google Trends, which allow sequential analysis of Google Books resources and of users' Internet queries (cf. Michel et al. 2011).

In order to understand what chronological corpus is one must grasp the basic distinction between synchrony and diachrony at the heart of structural linguistics. Synchrony is a study of language at a certain moment in time, where "moment" can last even several decades, provided there are no apparent changes in grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. As for diachrony, it exposes evolution of language taking place in the process of its development, usually over long periods, spanning even several centuries. However, corpus research supported by NLP tools enables a far more flexible approach to the time variable, since text samples consistent in terms of their typography, spelling and grammar can be annotated with their exact publication dates. Scientific description then focusses on the dynamics of the frequency change of specific lexemes (or other segments) in time, rather than on the evolution of word forms beginning with a hypothetical proto–language until the present state.

An important issue to be resolved is that of naming such an approach, whereby the chosen term would instate it in the domain of corpus linguistics. While social sciences and psychology use the term of "longitudinal" research, its equivalent in linguistics could be ‘microdiachrony’. Having said that, the term’s association with traditional diachrony and history of language could prove misleading. This is why it is more advisable to speak of chronological analysis and chronological corpora, where, similarly to diachrony, both terms contain a reference to time – gr. chronos.

Consequently, chronological corpus should be understood as a sequence of text samples consistent in terms of their spelling and grammar, corresponding to subsequent points on the axis of time (e.g. weeks, months etc.). Such a corpus would make it possible to explore the dynamics of the change of lexeme frequencies in successive periods using the method of time series analysis (cf. Gottman, 1981; Cryer, 1981; Pawłowski, 1998, 2001). A chronological corpus would differ from a diachronic one in that in the former texts are evenly spread in time and word forms remain unchanged, while in the latter it is the opposite: word forms must evolve to become object of interest and time spans between measurements may be of any length. It needs to be emphasised that the annotation of the time variable may be ignored (if such is the premise of the conducted research); a chronological corpus would then be treated as a synchronic one.

2. Chronological corpora

There exist corpora that are intrinsically arranged with regard to the time variable, e.g. literary outputs of some authors presented as Shakespearean Corpus, Corpus Thomisticum or Corpus Platonicum. If the date of creation of every piece of data in the corpus is known, the development of the text's stylostatistical properties over time can be established. If text chronology remains partly unknown, stylometric research can help to put undated works in the correct order (cf. Lutosławski, 1897).

But there is also another set of text corpora that seem to be naturally predestined to sequential analysis. Contrary to other genres or functional styles, press and media texts necessarily incorporate the date or even the time of their creation. This is of course little surprising, since media must comment upon actual events. Publication dates in the headers or footers of printed newspapers may be thus regarded as “time markup” that is invaluable as a Gutenberg era contribution to the sequential corpus research in the digital universe.

3. ChronoPress – features and origin

At present ChronoPress corpus contains texts representing Polish press of the post-war totalitarian period (1945-1954). Future extensions are planned to cover the entire period of the country's sovereignty (1918–2018). As the flow of press information was abundant even in the early post-war period, representative method of sampling has been applied. It has also been assumed that the minimum time spans, visible from the user level, are limited to subsequent months (the volume of text corresponding to weeks was too small to guarantee a sufficient level of representativeness). Apart from that it should be pointed out that the pace of public discourse in the times of printed press was slower than it has been in the digital world, so that months as time units can be regarded as sufficient to trace relevant events or processes.

In order to obtain reliable values of lexeme frequencies the number of words per month has been established as ca 120.000-140.000. Since sample size has been fixed to ca 250-300 words of continuous text, every month is represented by 480 samples and every year by 5760 samples (ca 1,5 million words per year). Equal numbers of words per month are important to guarantee that time series and other parameters generated from ChronoPress remain statistically unbiased with regard to the sample size. Selected newspapers represent a relatively broad spectrum of public post-war discourse of the totalitarian state. Particular titles to be included in the corpus have been selected according to two criteria: newspaper circulation (only titles with the highest values and national range have been considered) and target groups, as defined by the ideology of the time (first of all the working class, peasantry, army, youth, and, to a lesser extent, "intelligentsia"). The corpus is freely available through an interactive user interface.

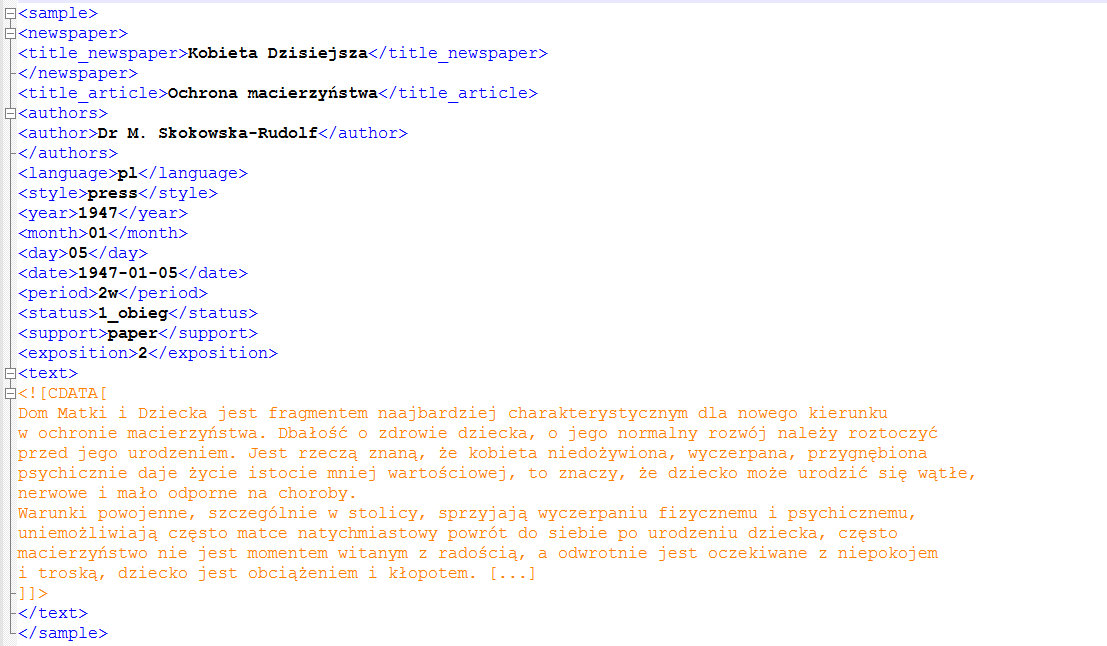

Data have been thoroughly sampled from Polish dailies and weeklies. Preparatory stages of analysis consist of: sample selection, scanning, OCR, markup with metainformation (XML scheme) and text curation. The corpus has been annotated morphosyntactically using Morfeusz tool which had been designed for the Polish National Corpus. Metadata (Fig.1) include newspapers’ titles, articles’ titles, authors’ names, exposition, and data support.

Fig. 1 Example of sample annotation with metadata

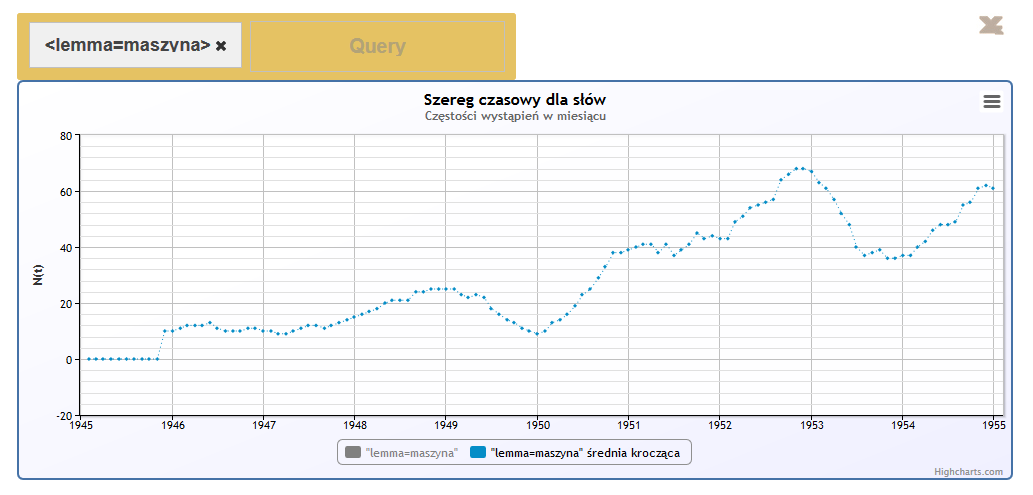

ChronoPress offers a variety of online linguistic and exploratory tools, such as concordances, frequency lists, word profiles and word maps. Its specific feature is, however, the possibility to generate time series. The analysis of lexeme frequency values displayed on an axis of time allows users to discover and explore the dynamics of events and phenomena represented in daily press over long periods of time.

Fig. 2 Moving average of the frequency of the lexeme machine (maszyna). It supports the view that despite the systemic inefficiency of communist economy technological progress was promoted in post-war Poland.

4. Goals of the presentation

ChronoPress allows to conduct a wide range of research in linguistics, contemporary history, cultural anthropology, media studies and communication science. The perspective adopted here is oriented towards the analysis of dynamic processes occurring in time rather than towards static states of language reflecting extralinguistic reality. The goal of the presentation is to provide an overview of the available exploratory techniques for chronological corpora, highlighting their explanatory power and limitations. In particular the following issues will be addressed and exemplified with empirical evidence from the ChronoPress corpus:

4.1. Manual and automated trend detection, modelling and interpretation

Long-term change in frequency of selected lexemes will be analysed as the expression of dominating topics of interest in public discourse, but also of social change imperceptible from the point of view on an average. Illustration material will include salient and informative examples generated from the ChronoPress database ( inter alia lexemes from the semantic fields war, health, technology). Since trend analysis requires some conceptualisation of time, various approaches to time will be presented and discussed (linear or circular, anthropological, political and astronomical).

4.2. Detection of events

Events are understood here as sudden changes, such as natural or technological catastrophes, wars, accidents etc. They manifest themselves as sudden rises in the lexeme frequency. This task will be illustrated with some examples generated from the ChronoPress corpus and from other online sources.

4.3. Testing the efficiency of statistical tools

The utility of the autocorrelation function (for univariate series) and of the cross-correlation function (for multivariate series) in the analysis of chronological corpora will be verified.

4.4. Comparison of ChronoPress and online resources

Informational potential and functionalities of the ChronoPress corpus will be compared with other online research tools, such as Google Ngram Viewer, Hansard Corpus and Polish National Corpus.

4.5. Word profiles analyses

Collocations and semantic profiles of selected lexemes in subsequent years will be generated (using Log Likelihood Ratio) and compared.

4.6. Automatic detection and annotation of named entities

Proper names and other named entities in Polish can be detected and annotated using Liner 2. Spatial distribution of toponyms identified by Liner 2 will be automatically displayed on a map and further analysed. Both tools have been created in the framework of the Clarin-PL project (http://clarin-pl.eu/en/home-page/).

- Brunet, E. (1981). Le vocabulaire français. De 1789 à nos jours. Paris–Genève: Slatkine, Champion.

- Cryer, J. (1986). Time series analysis. Boston: Duxbury Press.

- Gottman, J. M. (1981). Time-series analysis: a comprehensive introduction for social scientists. Cambridge, London etc.: Cambridge University Press.

- Lutosławski, W. (1897). The origin and growth of Plato’s logic. London, New York, Bombay: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Michel, J.-B., Shen, Y. K., Aiden, A. P., Veres, A., Gray, M. K., The Google Books Team, Pickett, J. P., Hoiberg, D., Clancy, D., Norvig, P., Orwant, J., Pinker, S., Nowak, M.A., Aiden, E. L. (2011). Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books. Science 14 (2011), Vol. 331: 176–182.

- Pawłowski, A. (1998). Séries temporelles en linguistique. Avec application à l'attribution de textes: Romain Gary et Émile Ajar. Paris, Genève: Champion-Slatkine.

- Pawłowski, A. (2001). Metody kwantytatywne w sekwencyjnej analizie tekstu [Quantitative methods in sequential text analysis]. Warszawa: Uniwersytet Warszawski, Katedra Lingwistyki Formalnej.

- Pawłowski, A. (2006). Chronological analysis of textual data from the Wrocław Corpus of Polish. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics (PSiCL) 41, 2006: 9-29.

- Salem, A. (1987). Pratique des segments répétés. Essai de statistique textuelle. Paris: Klincksieck.