Authors: Ching-Syang Jack Yue, Li-Hsing Ho, Wen-Huei Cheng

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: Classical Chinese, New Youth Magazine, Species Diversity, Multivariate Analysis, Logistic Regression

From Language Revolution to Revolutionary Language

In his insightful book The Language of the Third Reich, Jewish linguist Victor Klemperer pointed out, “One tends to understand Schiller’s distich on a ‘cultivated language which writes and thinks for you’ in purely aesthetic and, as it were, harmless terms [...] But language does not simply write and think for me, it also increasingly dictates my feelings and governs my entire spiritual being the more unquestioningly and unconsciously I abandon myself to it.” Thus he observed and detailed the language change during and after the rise of Hitler and Nazism, kept an invaluable record for study of the impact of language on the mind.

Klemperer was by no means the only scholar who was alert to the influence of language. In Chinese context, when May Fourth intellectuals followed the flow of turning the classical Chinese into something more colloquial in late Qing period and advocated a new literature/cultural movement, which was at its heart a language revolution, the idea under the action was that one cannot separate the language habits from the operation of mind. They started the vernacular movement in magazines like the New Youth, and hoped by modernizing language, they would empower the mind of the nation, modernize the culture, and eventually really modernize China, a task that 1911 revolution apparently did not fully succeed. The language revolution in early Republic was closely studied by many scholars. Our team also contributed by bringing in digital humanity methods, finding effective ways to tell the classical Chinese from modern Chinese by computer. It was when we analyzed the data of The New Youth Magazine that we noticed something rarely discussed by modern scholars: the language changed significantly in Volume 8 of the magazine, published on the eve of the rise of Chinese Communist Party.

According to our study, by the end of Volume 7 (published in 1920), modern vernacular Chinese had almost completely replaced classical Chinese as the main written language. However, the language of Volume 8 seems to be a new breed, deeply influenced by the translation of Soviet language and full of political jargons. It seems that right after success of language revolution, The New Youth Magazine immediately change the language again and promote a new kind of “revolutionary language” to advocate the Communism before the Chinese Communist Party was founded. Was there someone like Klemperer to observe the language change before the political turmoil? It called for further study. What we are doing here is to analyze the language turn in the late period of The New Youth Magazine. For comparison, we draw in two other materials. First, the editorials of United Daily News from 1951 to 1960, inherited the May Forth legacy and published in Taiwan before Taiwanese Modernist movement in 60s and Indigenized movement in 80s changing the written language violently. Second, the essays from the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Daily from 1971 to 1989, published in mainland China before the Chinese economic reform.

There are two types of data: one is structured data (with a high degree of organization) and the other is unstructured data. Most of the textual data are unstructured and quantifying them often requires certain knowledge about the application domain. We need to create a relational structure for the textual data before plugging classification methods. In particular, we use the notion of Exploratory Data Analysis (or EDA, proposed by famous statistician J.W. Tukey in 1977) to evaluate potential variables which can differentiate the language styles of Volume 7 and Volumes 8~11 in New Youth Magazine. According to our previous study of writing style for Volumes 1~7, we found that the number of words, the number of different words (or vocabularies) and their distribution, in addition to function words in classical and modern Chinese, can be used to distinguish Chinese writing styles. We also include species diversity indices, such as Simpson index and entropy (or Shannon index).

Since there are more than 30 variables, we also consider data reduction methods, such as principle component analysis, to include fewer variables. Then, we apply classification methods (logistic regression) to judge the style of an article is close to Volume 7 or Volumes 8~11. Also, to avoid over parameterization (i.e., using too many unnecessary variables), we use cross validation to check whether the model is stable. The regression model is first built based on training data and then applied to the testing data. The fitting accuracies of training data and testing data are recorded separately, and these two numbers of accuracy should be close if the model is stable. For every simulation run, we randomly separate the training data and testing data into proportions of 90% and 10%, respectively. Based on 100 simulation runs, the regression model is fairly stable since it has very similar fitting accuracy (and small standard errors) for training and testing data.

Next step, we apply the constructed regression model to the articles from two newspapers, United Daily News and People’s Daily. Both newspapers have about 500 articles and Table 1 shows their classification results. The United Daily News is published in Taiwan and the Soviet Union should have little influence on this newspapers. As expected, only 10% articles are classified to the group of “Revolutionary Language.” On the other hand, more than 50% of articles from People’s Daily are classified to “Revolutionary Language.” This matches to our anticipation, since the articles from People’s Daily are published in 1971~1989, in which period China had close link with the Soviet Union.

| No. of Article | Classified to “Revolutionary Language” | ||

| No. of Article | Proportion | ||

| United Daily News | 550 | 57 | 10.36% |

| People’s Daily | 534 | 308 | 58.68% |

Table 1. Classifications of United Daily News and People’s Daily

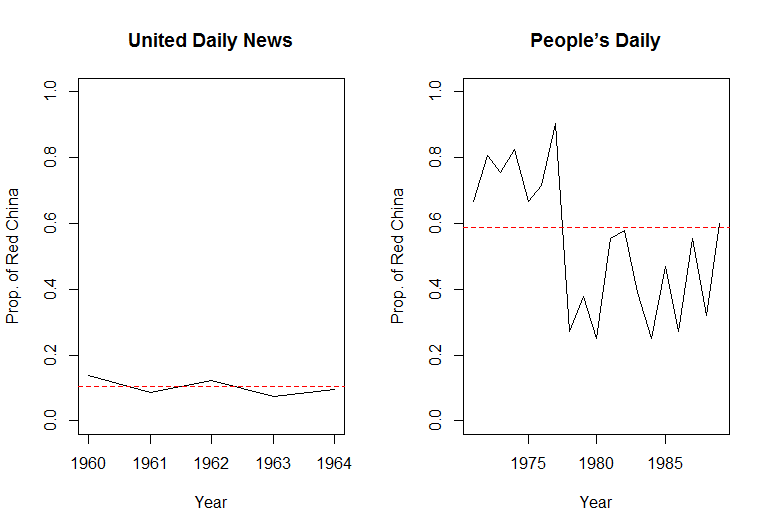

Similar to the cross-validation for the articles from the New Youth magazine, we can fit the regression model to the articles from two newspapers year by year. Figure 1 shows the yearly classification results. It seems that the results of United Daily News are fairly stable and the yearly results lie around the average (red dotted line). The fitting results of People’s Daily somehow show an inconsistence pattern. The average proportion of “Revolutionary Language” is 76.3% for the articles in 1971~1977 and is 39.2% in 1978~1989 (the overall average is the red dotted line).

The yearly classification results of People’s Daily are interesting and very encouraging. The first stage of China’s reform and opening is between 1978~1989, under the formal leader Deng Xiaoping. China started to open to the outside world gradually since 1978, and it also triggers the economic blooming of China at the end of 20 th century. Figure 1 suggests a similar story. The proportion of “Revolutionary Language” (under the influence of Soviet Union) articles is larger before 1978 and has a radical change ever since 1978 until 1989, coincide with the years of reform and opening in modern China.

2015 marks the 100th anniversary of The New Youth Magazine. By employing the digital humanity methods and focusing on the language change of the latest few volumes that so far rarely discussed by scholars, we hope to make some new contribution to the study of both The New Youth Magazine and the writing style of modern Chinese language. Our study shows that the styles of articles from United Daily News are close to that of Volume 7 in New Youth Magazine, while those from People’s Daily have about equal probability for being classified to Volume 7 or to Volumes 8~11. This implies that the Chinese writing styles of Taiwan and mainland China are different and the writing style of mainland China is likely to be influenced by the Soviet language.

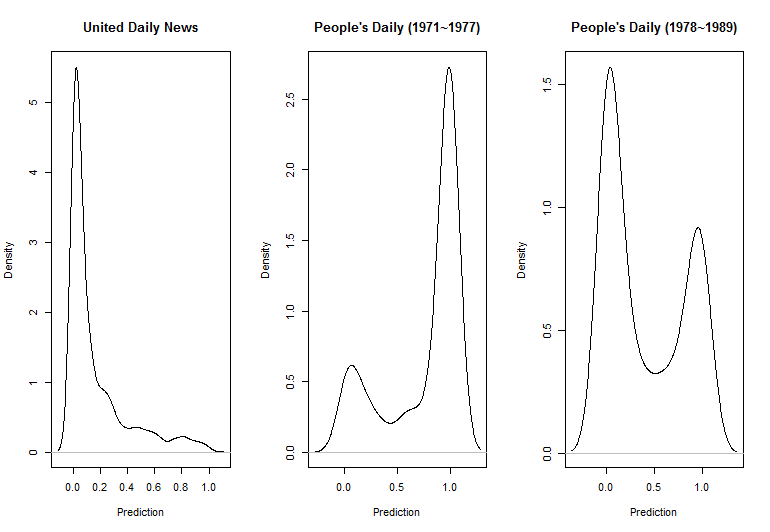

Also, the change of “Revolutionary Language” in 1978 seems to indicate a new possible writing style. Judging from the proportion of “Revolutionary Language,” those of 1978~1989 lie between “Revolutionary Language” and United Daily News, and it seems that the writing style of China turned into a new direction in 1978~1989 (namely, Reform China). Figure 2 shows the predicted results (after kernel smoothing) of all articles, with a value near 1 indicating style closer to “Revolutionary Language” and vice versa. If we treat United Daily News and 1971~1977 People’s Daily as two extremes, then 1978~1989 People’s Daily is somewhat in between (or a mixture of) these two extremes. It would be interesting to explore the writing style in China since 1978. For example, we can further compare the writing styles of China according to the following three periods, 1978~1989 (first stage), 1989~2002 (economic blooming), and 2002~today (modern China).

- Agresti, A. (1990). Categorical Data Analysis. New York: Wiley.

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., and Friedman, J. (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. 2nd Edition, Springer Series in Statistics.

- Ho, L., Yue, C. J., and Cheng, W. (2014). From Classical Chinese to Modern Chinese: A Study of Function Words from New Youth Magazine. Journal of the History of Ideas in East Asia, 7: 427-54.

- Tukey, J. W. (1977). Exploratory Data Analysis. Addison-Wesley.