Authors: Mark Wolff

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: classification, stylometry, oulipo, queneau, matrix

Oulipian Stylometry

The Oulipo, or Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, is a group of writers in Paris who for over fifty years have experimented with algorithmic techniques for writing and reading literature. Raymond Queneau, one of the group’s co-founders, proposed a method in 1964 for analyzing the syntactic structure of texts written in French, and he believed that the method, which he called matrix analysis, could provide a measure of an author’s style.

What can matrix analysis contribute to stylometry? Apart from its origins as a form of computational play for play’s sake (Wolff, 2007), matrix analysis offers an alternative to lexically based techniques for authorship attribution such as Burrow’s Delta (2002). Rybicki and Eder reported that Delta does not work as well for texts written in French as for those in English and German (2011). Antonia, Craig and Elliott have shown that analyzing the frequencies of lexical n-grams where n > 1 does not usually yield very good results (2014). Researchers have developed syntactical methods based on bigrams of labels for a simplified parsing of texts (Hirst and Feiguina, 2007) and on correlations between semantics and the structures of dependent and independent clauses (Allison et al., 2013). In the latter study the researchers concluded that their definition of style “entailed […] a method for looking for it” (28). The early Oulipo would have agreed with this approach. Recognizing that an author aware of how he or she used words syntactically might apply Queneau’s matrix analysis to change his or her “manner,” François Le Lionnais (the other co-founder) claimed that matrix analysis could serve as a “literary prosthesis” exemplifying the vocation of the group (Bens, 2005: 246). For Le Lionnais, the most important focus of the Oulipo should be the synthesis of new possibilities for understanding literary phenomena (Oulipo, 1973: 17). Matrix analysis enables the identification of significant syntactical patterns for further inquiry into an author’s style. These patterns would be difficult to ascertain without a method like the one developed by Queneau.

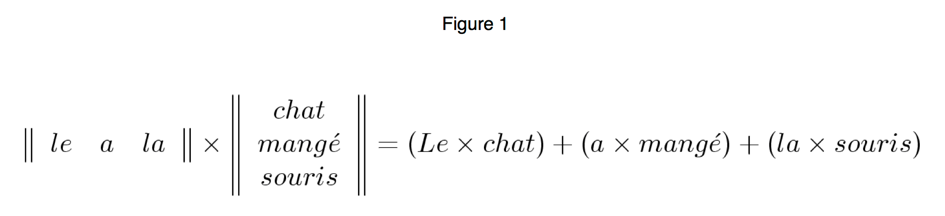

Queneau devised a grammatical schema of the French language for describing the construction of word pairs using a system similar to linear algebra (1964). He began by dividing all elements of speech into two categories: signifiers, which include nouns, adjectives, and verbs (except avoir and être); and formatives, which include everything else ( avoir, être, pronouns, articles, conjunctions, prepositions, adverbs, interjections, etc.). Given a sentence, one can construct two matrices where the first matrix contains all formatives and the second all signifiers:

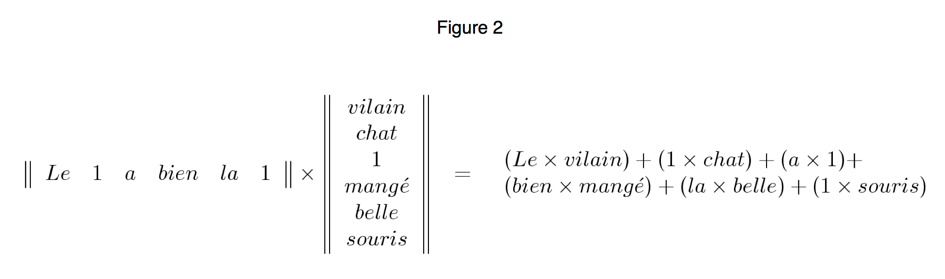

If a sentence contains two consecutive formatives or signifiers, one can use a unitary element to construct the matrices:

By adopting the conventions that neither (1 × 1) nor (Y × 1) + (1 × Z) are allowed within a sentence, one avoids uninteresting or redundant word pairs.

Queneau proposed observing the distribution of formatives and signifiers in a text using the relation F + Uf = S + Us, where F is the number of formatives, S the number of signifiers, Uf the number of unitary elements paired with signifiers (1 × Z), and Us the number of unitary elements paired with formatives (Y × 1). Noting that even if an author like Flaubert worked tirelessly to vary how he wrote, Queneau believed that this distribution could serve as a “potential” but unconscious indicator of the author’s style (1965: 319).

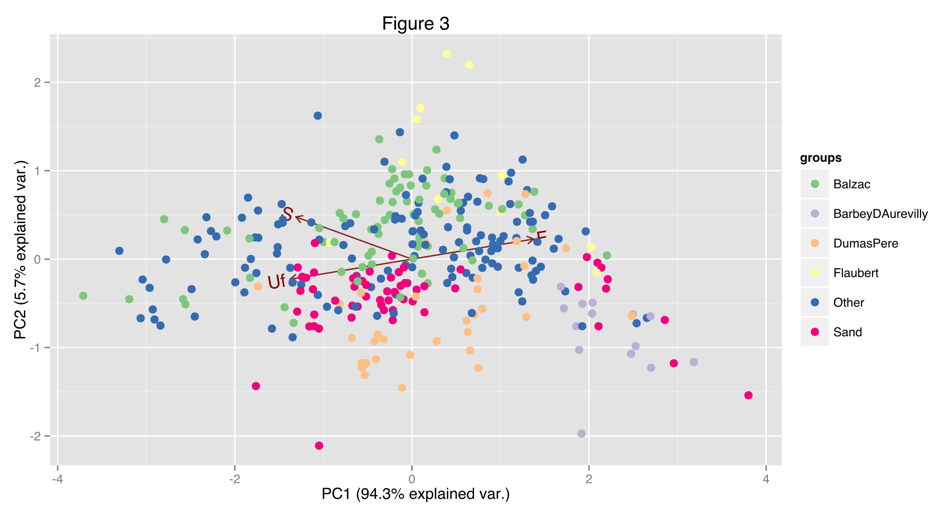

In order to test Queneau’s hypothesis, I applied his matrix analysis to a corpus of 328 nineteenth-century French novels from the ARTFL-FRANTEXT database using Helmut Schmidt’s part-of-speech tagger (1995). Figure 3 is a biplot of a principal components analysis of scaled values for F, S and Uf (Us is excluded to avoid collinearity) and the graph shows that works by the authors Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, Alexandre Dumas and Honoré de Balzac cluster separately whereas works by George Sand form distinct clusters.

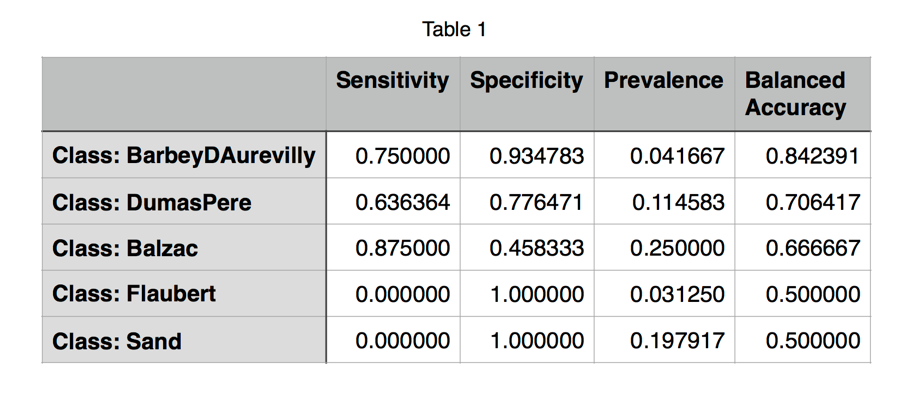

Table 1 indicates the results of using support vector machines with a radial basis function kernel to build a classification model for the texts (Kuhn, 2015). Sixty-seven percent of the corpus was used for training the model with 10-fold cross-validation. A one-against-one method was used for classifying the test set (Karatzoglou, 2004: 7-8). The results show a moderate authorial signal in the works of Barbey d’Aurevilly and weaker signals for Dumas and Balzac.

To build a better model using matrix analysis, one can observe the distribution of bigrams of matrix analysis pairs in the corpus. Given the labels F for (Y × 1), S for (1 × Z), and B for what Queneau called a biword (Y × Z), one can transcribe a text into a series of these letters. For instance, the sentence from George Sand’s Indiana (1832):

(Toute × 1) (sa × conscience), (c’ × 1) (était × 1) (la × loi); (toute × 1) (sa × morale), (c’ × 1) (était × 1) (son × droit).

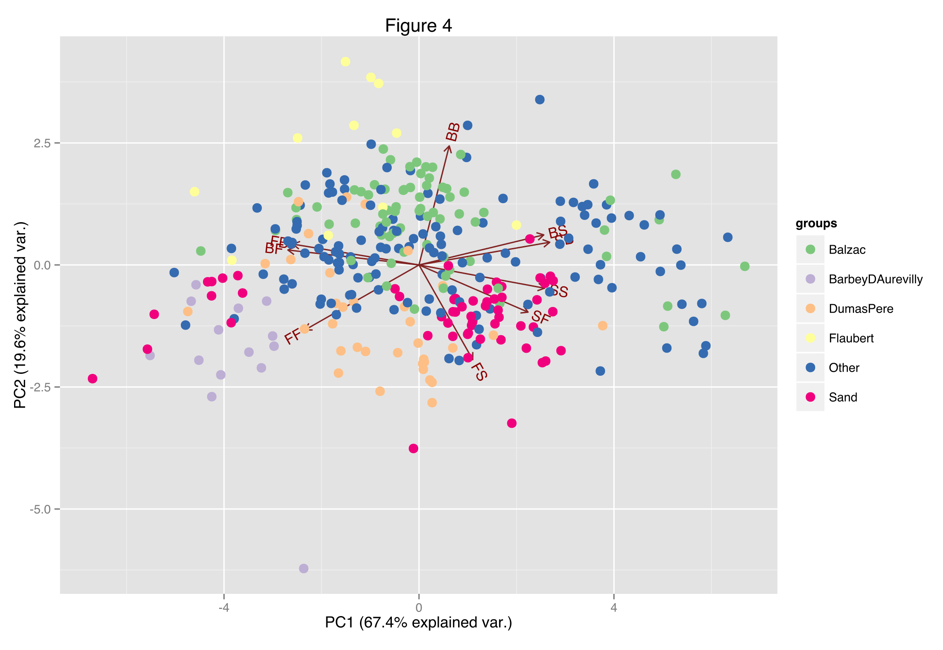

can be represented as FBFFBFBFFB. With the feature set of bigrams FF, FB, BF, BB, BS, SB, SS, SF, and FS, one can analyze its distribution within the corpus. Figure 4 is a biplot of a principal components analysis of the corpus with the nine bigrams as variables and suggests that at least some authors do have measurable differences in style.

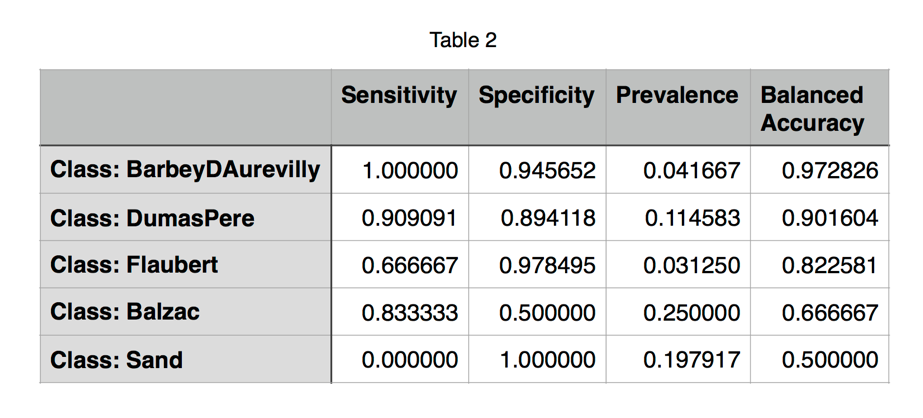

Table 2 shows the results of building a model with support vector machines to classify the texts by author according to the distribution of bigrams.

The model can identify the styles of Barbey d’Aurevilly and Dumas with very good accuracy, and it can detect authorial signals in works by Flaubert and Balzac. The model does not do well identifying works by Sand because they seem to evince two distinct styles (as suggested by Figure 4). The small cluster of works by Sand on the left side of the graph include François le champi, Elle et lui, Le Château des désertes, La Mare au diable, Consuelo, Indiana, Lélia, and La Comtesse de Rudolstadt. The predominance of formatives in this cluster is perhaps indicative of a more conversational style: such an hypothesis would require further analysis.

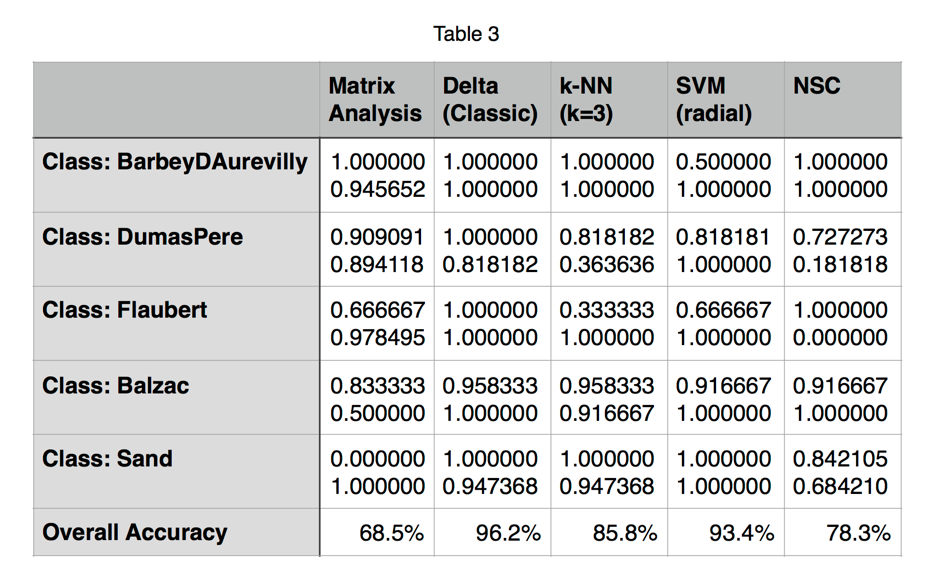

Compared to other classification methods based on wordlists, matrix analysis does not deliver as high a level of accuracy. Table 3 summarizes the sensitivity and specificity of several classification models with different statistical techniques for the five selected authors using the classify() function of the R software package stylo (Eder et al., 2013):

To minimize the effects of semantic variation, the wordlists for classification with stylo were culled 100% (only those words that appear at least once in every text were included).

Despite the low accuracy of matrix analysis, it is possible to identify sample sentences that exemplify an author’s style with sequences of bigrams. In Figure 4 the left group of Sand’s texts clusters near the vectors for FF, BF and FB. Scanning the texts for the highest relative frequency of these bigrams yields sentences such as this from Sand’s Consuelo (1842):

(Il × faut) (que × 1) (je × sache) (comment × 1) (elle × 1) (se × tient), (ce × 1) (qu’ × 1) (elle × fait) (de × 1) (sa × bouche) (et × 1) (de × 1) (ses × yeux). BFBFFBFFBFBFFB

The syntax of this sentence as schematized by matrix analysis contains within it the syntax of the previously quoted sentence, inviting further inquiry into how Sand constructed her texts. Although Sand most likely did not think of her writing style in the terms conceived by Queneau, matrix analysis represents a method for thinking about style that not only measures how words are used but can also inform potentially the act of writing and reading. Lexically-based techniques consider texts as “bags of words” with structure-less frequencies, but matrix analysis approaches texts as objects that have undergone a process of development. As an Oulipian procedure, matrix analysis allows the reader to detect reproduced and reproducible patterns through an interactive process of textual exploration.

Queneau’s matrix analysis represents an analytical method for defining style that classifies texts according to their structure. The Oulipo in the 1960s made a distinction between the quality of works of literature and the potentiality of the methods used to create works of literature (Bens, 2005: 80). Practitioners of computational text analysis can observe a similar distinction between the accuracy of text classification and the potentiality of classification methods for understanding literature. If style implies how words are used more than what words are used, stylometry should seek to better understand how words are used. The Oulipo provides us with an example of this kind of inquiry into computationally revealed text structures. Queneau performed small experiments with matrix analysis, but Le Lionnais imagined the possibility of harnessing machines to support the necessary calculations on a larger scale (Bens, 2005: 246). Following the Oulipian notion of “plagiarism by anticipation” (Oulipo, 1973: 23), we can understand matrix analysis as a precursor of stylometry in the digital humanities.

- Allison, S., Gemma, M., Heuser, R., Moretti, F., Tevel, A. and Yamboliev, I. (2013). Style at the Scale of the Sentence. Literary Lab 5. Stanford University. Retrieved from <http://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet5.pdf>

- Antonia, A., Craig, H. and Elliott, J. (2014). Language chunking, data sparseness, and the value of a long marker list: explorations with word n-grams and authorial attribution. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 29/2: 147–63. DOI: 10.1093/llc/fqt028

- Bens, J. (2005). Genèse de l’Oulipo 1960-1963. Bordeaux: La Castor Astral.

- Burrows, J. (2002). ‘Delta’: a Measure of Stylistic Difference and a Guide to Likely Authorship. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 17/3: 267–87. DOI: 10.1093/llc/17.3.267

- Eder, M., Kestemont, M. and Rybicki, J. (2013). Stylometry with R: a suite of tools. In: Digital Humanities 2013: Conference Abstracts. University of Nebraska--Lincoln, NE: 487-89.

- Hirst, G., and Feiguina, O. (2007). Bigrams of Syntactic Labels for Authorship Discrimination of Short Texts. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 22/4: 405–17. DOI: 10.1093/llc/fqm023

- Karatzoglou, A., Smola, A., Hornik, K. and Zeileis, A. (2004). kernlab – An S4 Package for Kernel Methods in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 11/9: 1–20.

- Kuhn, M. (2015). caret: Classification and Regression Training. Retrieved from <http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caret>

- Oulipo (1973). La Littérature potentielle (Créations Ré-créations Recréations). Paris: Gallimard.

- Queneau, R. (1964). L’Analyse matricielle du langage. Etudes de linguistique appliquée, 3: 37–50.

- Queneau, R. (1965). Bâtons, chiffres et lettres. Paris: Gallimard.

- Rybicki, J. and Eder, M. (2011). Deeper Delta across genres and languages: do we really need the most frequent words? Literary and Linguistic Computing, 26/3: 315–21. DOI: 10.1093/llc/fqr031

- Schmid, H. (1995). TreeTagger: a language independent part-of-speech tagger. Retrieved from <http://www.cis.uni-muenchen.de/~schmid/tools/TreeTagger/>

- Wolff, M. (2007). Reading Potential: The Oulipo and the Meaning of Algorithms. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 1/1.