Authors: Armin Hoenen

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: simulation, Stemmatology, force dichotomique, bifurcations

Silva Portentosissima - Computer-Assisted Reflections on Bifurcativity in Stemmas

1. Introduction

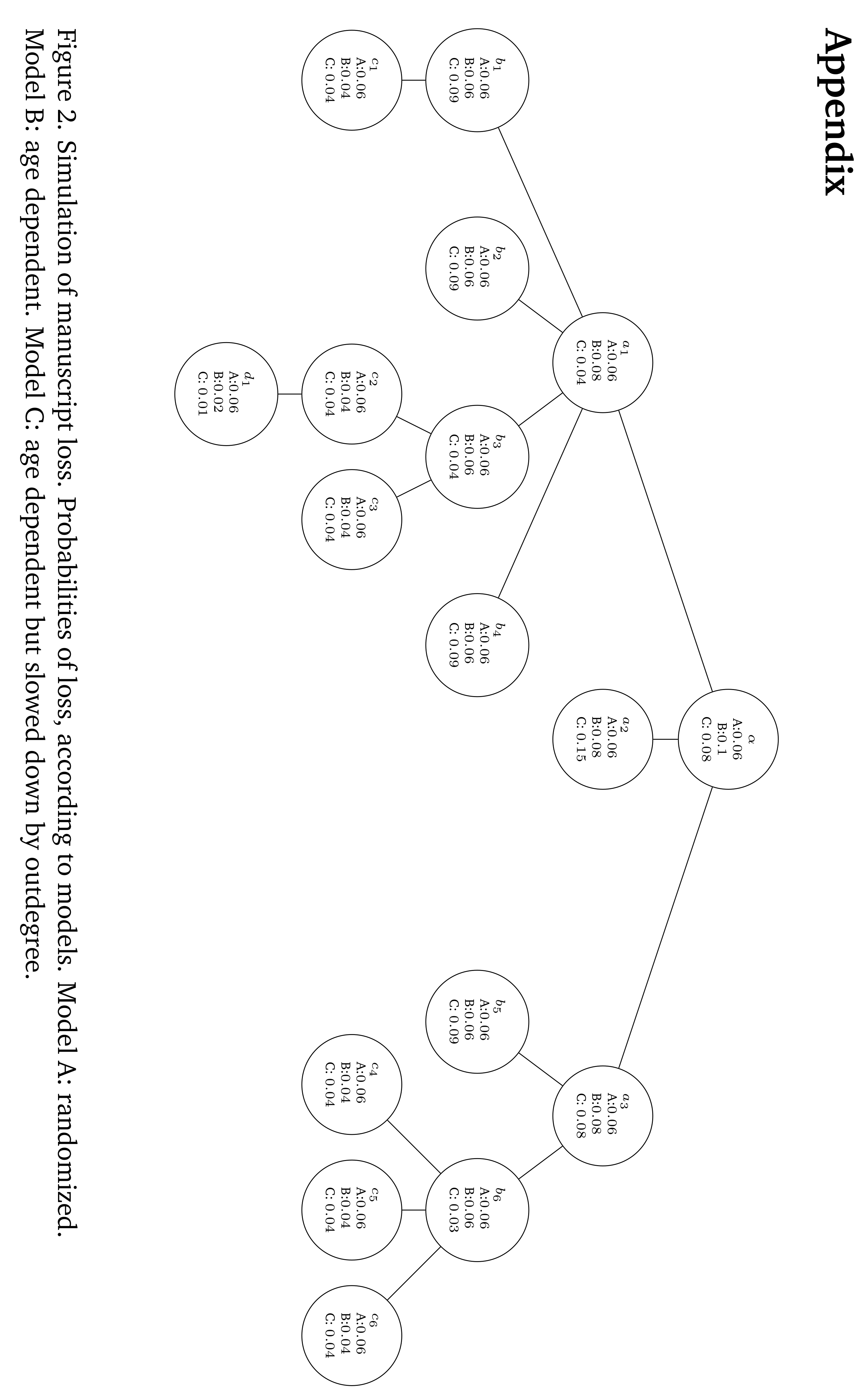

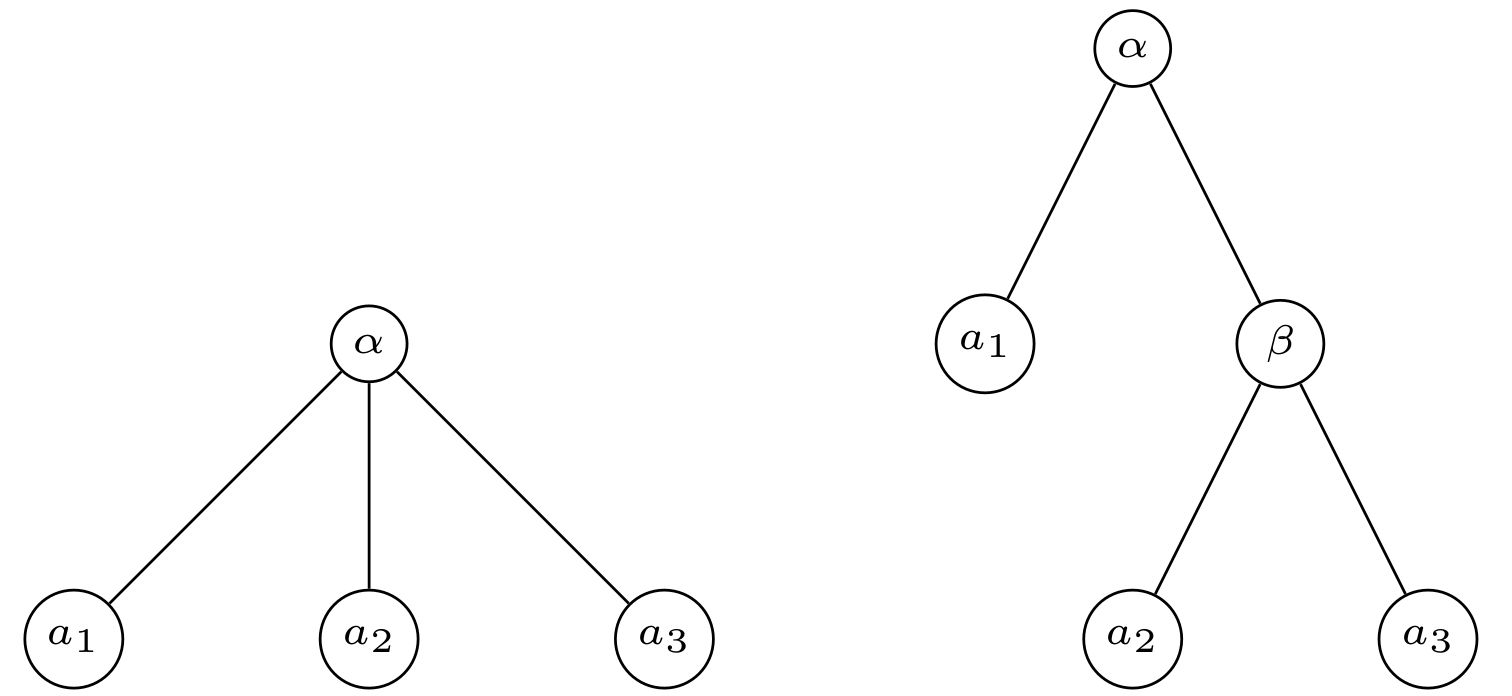

In 1928, the philologue Joseph Bédier explored contemporary stemmas and found them to contain a suspiciously large amount of bifurcations. He gave two potential reasons, one being that the editors constructing a stemma with a bifurcation below the root node, could freely choose the variants for their base text. The second reason termed force dichotomique postulates that constructing a stemma, because editors are always comparing manuscript pairs, they tend to overseparate. This is illustrated in Figure 1. The philologue would postulate a common ancestor for the closer pair and attach the third sibling together with this ancestor to the parent node producing two bifurcations, where there was a multifurcation originally.

(Maas, 1937) acknowledges a large amount of bifurcations in stemmas for recensions of Greek texts, but points out that this is rather unsurprising taking into account the number of possible stemmas and the proportion of bifurcations therein. (Felsenstein, 1978) computes the amounts of entirely bifurcating trees for n labelled leafs, which is certainly correlated with the number of predominantly bifurcating trees (and of root-bifurcating trees). As one can see, the proportion of bifurcating trees steadily declines, weakening Maas’ argument.

(Haugen, 2015) analysed collections of stemmas and found that Bédiers reason number two seems to hold independent of provenience. (Trovato, 2014) found that a realistic estimate of the percentage of lost manuscripts for medieval and earlier traditions ranges realistically above 73%. Related discussions and recent developments are reflected in projects such as Stemmaweb and the Parvum lexicon Stemmatologicum.

In this paper, the argument is introduced and investigated that, with a large amount of lost manuscripts, the amount of bifurcations in the true stemmas could naturally be high because of the transformations stemmas undergo when manuscript loss prunes away whole branches and leafs at a rate higher than 73%.

2. Distributions of outdegrees of manuscripts

Two basic distributions are most obviously historically interpretable, a normal distribution and an exponential distribution. In considering the outdegrees to be normally distributed, we assume, that there is one certain number of copies which is most probable, peaking the others; the more the outdegree diverges negatively or positively, the fewer manuscripts with this outdegree will be found. This could translate into a hypothetical historical projection, where many manuscripts of a tradition were copied and wore off at similar rates. Assuming an exponential distribution, things become more hierarchical. For instance, a powerful organization declares some of the manuscripts authoritative which would lead to certain manuscripts being copied many times more than others.

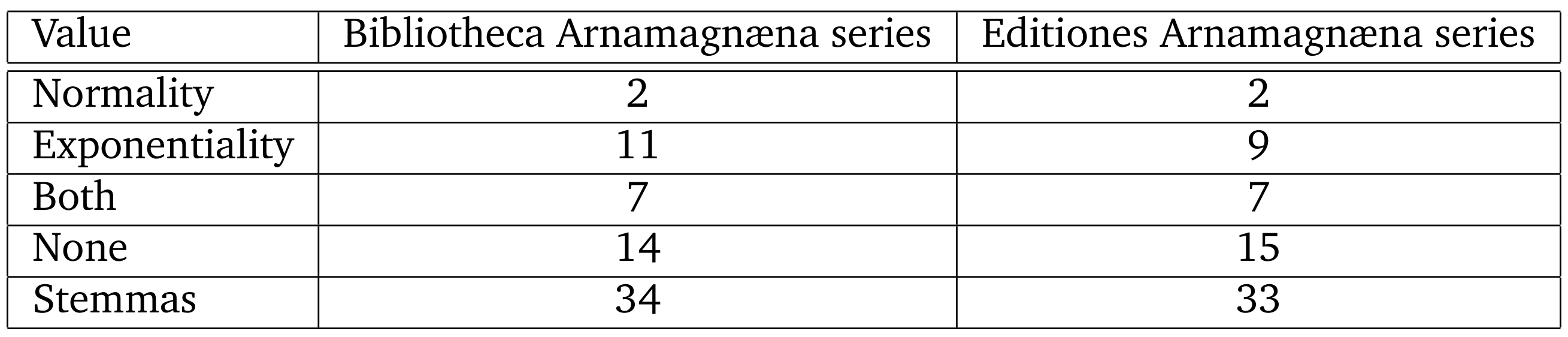

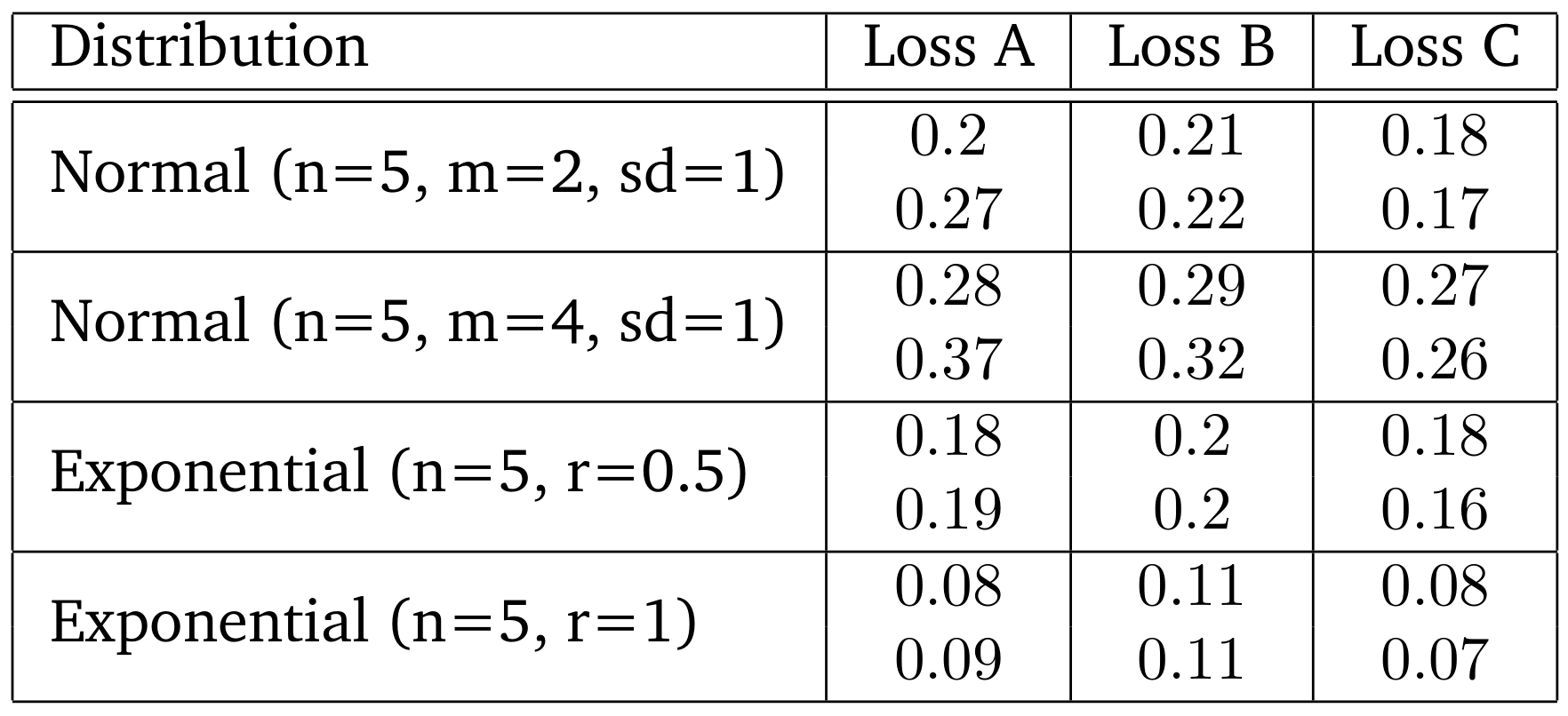

(Haugen, 2015) lists a table with the numbers of furcations (though not leafs) in two collections of stemmas for editions of Old Norse texts. Transforming these furcations into vectors, we conduct the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965), and the exponentiality test by Kolmogorov-Smirnov (which are both robust even for smaller sample sizes) using the software R. 1 This results in an estimate on which distribution these stemmas entail for manuscript copying. However, stemmas with only identical values or only 2 furcations are skipped due to not being testable with the above chosen tests. Table 1 reveals a tendency towards exponentiality. Applying other tests for additional distributions, the weibull and log-normal distributions fitted the data best in terms of likelihood, suggesting a similar scenario. 2

3. Experiment

In order to assess the above mentioned hypothesis, we need large numbers of underlying stemmas from which loss can be simulated and an appropriate model of manuscript loss. Then, we can simulate a large number of stemmas and manuscript loss, whereafter we count the number of bifurcations. Using simulations especially in large scale scenarios is sometimes the only possibility of assessing historical data, especially considering limits imposed onto empirical studies through data sparsity and other hindances.

3.1. Manuscript loss

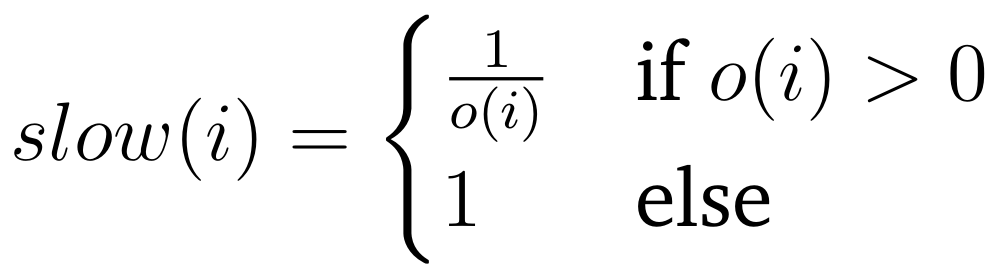

Historical loss does not affect all manuscipts evenly. (Canfora, 2002) found private exemplars to be less affected whereas since libraries tend to be burnt in wars, public exemplars suffer loss more easily. Many other factors (climate, authoritativity, etc.) excert influence on manuscript loss most of which have never been made subject to generalizable quantifications and it is questionable if this can ever be done. Herein, we elaborate a simple model of loss using only two basic assumptions. We simulate loss of 73-100% where each node gets a probability related to its age (the older the more probably lost) and its outdegree (the more copied, the more probably kept in good conditions, the less probably lost). Since aging is considered to be stronger than preservational effort, we square the age dependent parameter. The probability of loss for each node is thus determined by

where l is the height of the current node i incremented by 1 and slow(i) is the outdegree slowdown function:

where o(i) is the outdegree of node i. Note, that there is no distinction for nodes with an outdegree of one and leafs. This model of loss produced rather desirable loss probability distributions as is exemplified in the Appendix. However, we also use pure randomization of loss with equal probabilities among all nodes and randomization for probabilities as described but without squaring.

3.2. Simulation

For the simulation, we use R and Java. 3 First, for simulating normally distributed copying, we generate distributions randmonly drawn from a normal distribution using the R function rnorm. Since rnorm produces real numbers and negative numbers, we round all values and leave negative values and zeros aside. Since this may lead to a distortion of the so-sampled distribution deviating from a normal distribution, we test for the desired shape and only keep distributions which have a p-value above 0.05. This distribution is now our distribution of outdegrees in the to be simulated stemma, each value represents one outdegree. Starting with root, we randomly choose an outdegree (or make the node (not root) a leaf with a probability of 0.2) and add as many children to the actual node as this outdegree. For each of the so-generated children, we draw another outdegree and add as many children, recording them in the next generation. We iterate the process until all outdegrees are applied exactly once.This results in a differing number of leafs and a differing size of the tradition for each simulation. Since medieval traditions were probably not equal in size, the effect of this sampling is not controlled for further. 4

With each tradition, loss is simulated in the three above described ways. We keep all nodes, which are on the path from root to any survivor but delete all other lost nodes. What remains is the true reconstructible stemma (TRS). Since philologues do not have sufficient information (and probably time) for the reconstruction of entirely lost branches, which would be too spurious an endeavour anyway, the stemma we simulated is the maximally faithful reconstruction given our simulated ground truth.

4. Results and discussion

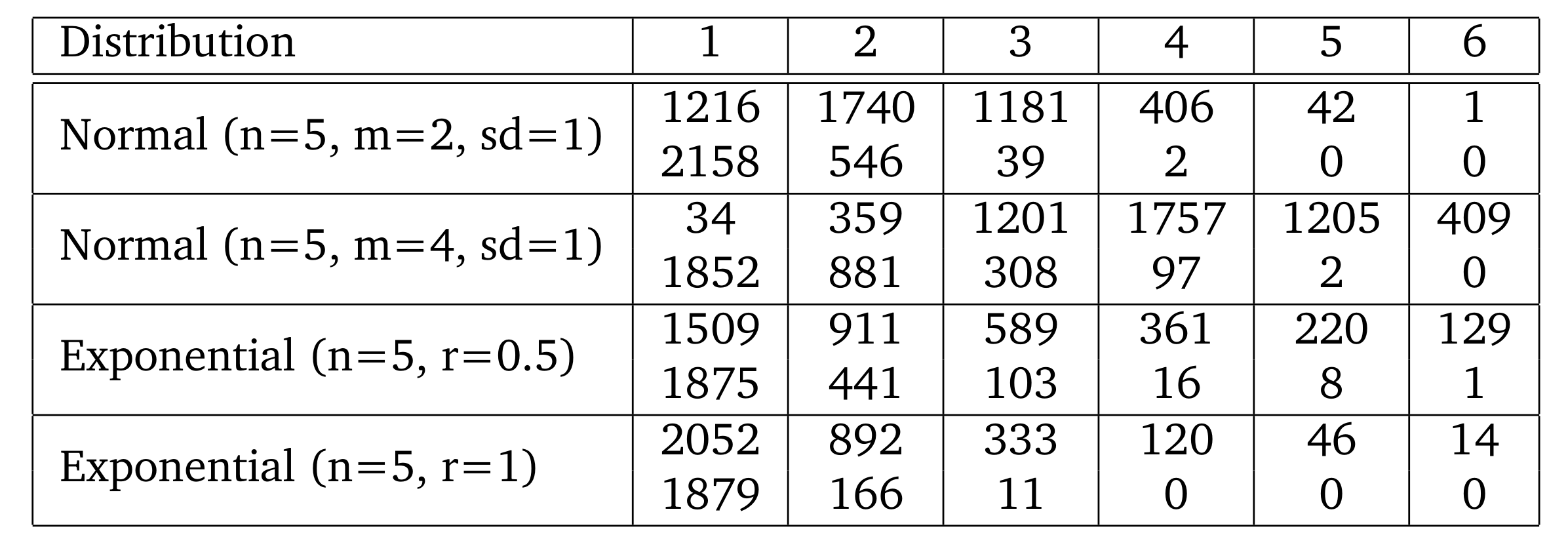

Results can be seen in Tables 2 and 3. The simulated traditions ranged in size from 4 to more than 60 and after loss from 1 to around 20 manuscripts. Percentages of bifurations (even excluding leafs, as in Haugen (2015)) are below the observed values for the collections examined in the previous literature. Under more keeping nodes, which are on the path to root for any survivor as reconstructibles results in a much larger incidence of unifurcations, not bifurcations in the stemmas after loss has applied. Therefore, some model of contraction shall be applied in subsequent research. With a mean of 2 producing large numbers of bifurcations, after loss, their number is reduced sharply in contrast with unifurcations and leafs. Thus, loss at high rates generally affects furcations of higher orders much more, leading to a naturally higher incidence of bi- and unifurcations and most of all obscuring an underlying distribution of original copies. Aditionally, probably there are too few reconstructions of nodes with indegree and outdegree 1. In other words, philologues could tend to view a copy rather as sloppy than as a copies copy, which would contribute to making bifurcations more common in actual stemmas.

5. Conclusion

Although the simulation is an approximation, the values suggest, that indeed the proportion of bifurcations is suspiciously large in the collections in the literature. On the other hand, Maas was probably right in expecting a larger amount of lower order furcations. However, not their proportion among all possible stemmas, but the effect of massive loss of manuscripts leads to a large probable proportion of those in a pruned TRS.

- Bédier, J. (1928). La tradition manuscrite du 'Lai de l'Ombre': Réflexions sur l'Art d' Éditer les Anciens Textes. Romania, 394: 161-96, 321-56.

- Canfora, L. (2002). Il copista come autore. Palermo: Sellerio.

- Felsenstein, J. (1978). The number of evolutionary trees. Systematic Zoology, 27(1): 27–33.

- Haugen, O. E. (2015). The silva portentosa of stemmatology bifurcation in the recension of old norse manuscripts. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30(2).

- Maas, P. (1937). Leitfehler und Stemmatische Typen. Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 37(2): 289–94.

- Satman, M. H. (2014). Rcaller: A software library for calling r from java. British Journal of Mathematics & Computer Science, 4(15): 2188–96.

- Shapiro, S. S. and Wilk, M. B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52: 591–611.

- Trovato, P. (2014).Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Lachmann’s Method, A Non-Standard Handbook of Genealogical Textual Criticism in the Age of Post-Structuralism, Cladistics, and Copy-Text. libreriauniversitaria.it.