Authors: Adrien Barbaresi, Hanno Biber

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: Toponym Resolution, Visualization, Digital Literary Studies, German Literary History, Methodology

Extraction and Visualization of Toponyms in Diachronic Text Corpora

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on the extraction of German and Austrian place names in historical texts. It is part of a cooperation between the Berlin-Brandenburg and the Austrian Academies of Sciences. The latter is the holder of the text basis for this investigation, the digitized version of the satirical literary magazine "Die Fackel" ("The Torch"). It has been originally published and almost entirely written by the satirist and language critic Karl Kraus in Vienna from 1899 until 1936, and contains a considerable variety of toponyms (Biber, 2001).

2. Gazetteers and lists

Toponym resolution often relies on named-entity recognition and artificial intelligence (Leidner and Lieberman, 2011). However, knowledge-based methods using fine-grained data – for example from Wikipedia – have already been used with encouraging results (Hu et al., 2014).During the 20th century there have been significant political changes in Central Europe that have severely affected toponyms, so that geographical databases lack coverage and detail. Consequently, the database we develop follows from a combination of approaches: gazetteers are curated in a supervised way to account for historical differences,and current geographical information is used as a fallback.

First, a cascade of filtersis used: (1) current and historical states (e.g. Austria-Hungary); (2) regions, important subparts of states, and regional landscapes (e.g. Swabia); (3) populated places; (4) geographical features (e.g. valleys). Wikipedia's API is used to navigate in categories and to retrieve coordinates, which are completed by hand for states and regions.Second, current information is also compiled from the Geonames database 1: data for European countries are retrieved and preprocessed(variants and place types).

In order to exclude common and proper nouns, the German version of the Wiktionary serves as a reference 2, and registers of frequent surnamesand family names, as well as well-known persons (especially writers) are built using Wikipedia and Wikidata.

3. Extraction

The texts were digitized, manually corrected as well as manually annotated with respect to the names of persons and institutions, so that most proper nouns which are not place names can be excluded from the study.

The tokenized files of works to be analyzed (Jurish and Würzner, 2013) are filtered and matched with the databaseby finite-state automatons: toponyms are extracted using a sliding window (for multi-word names up to three components). Disambiguation being a critical component (Leetaru, 2012), an algorithm similar to Pouliquen et al. (2006), who demonstrated that an acceptable precision can be reached that way,guesses the most probable entry based on distanceto Vienna (Sinnott, 1984), contextual information(closest-country, last names resolved), and importance (place type, population count).

4. Visualization

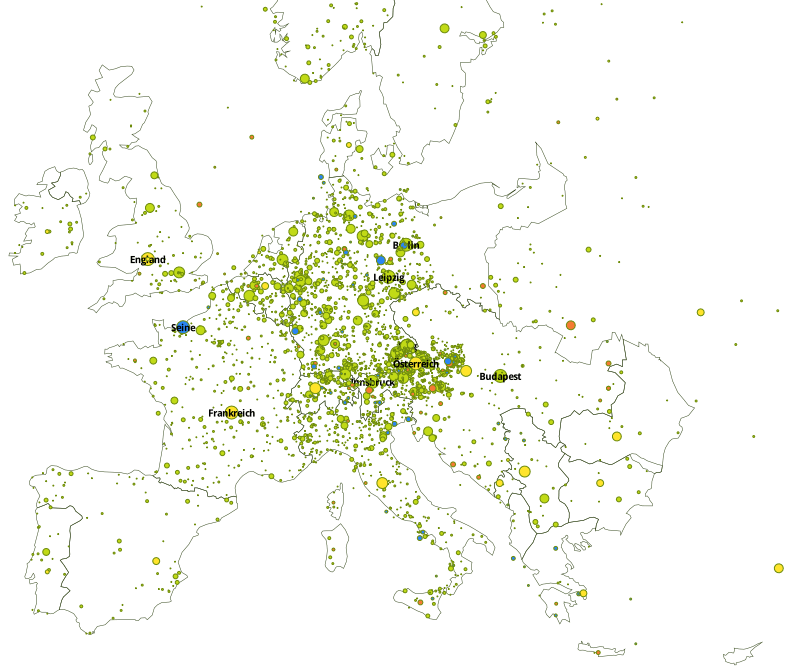

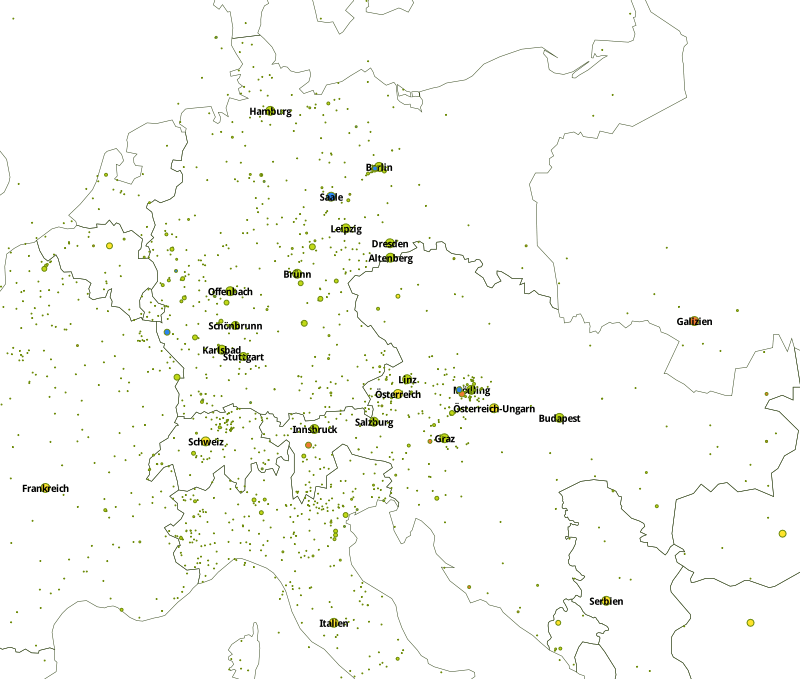

The results are projected on a map of Europe with boundaries of 1914 3 using TileMill 4. They are customized with CartoCSS: multiple trial-and-error iterations are performed concerning both data quality and graphical output. The two experimental maps belowground on the same data, they result from different settings.

Map 1– Experiment on European scale with boundaries of 1914 (yellow: sovereign territories; orange: regions; green: populated places; blue: geographical features)

Map 2– Central Europe, experiment with a restrictive filtering

5. Discussion

Potential conceptual caveats include previous times as well as fictitious places, especially names which can refer to mythological and actual places of Ancient Greece or Rome. Practical caveats are for instance false localizations due to disambiguation errors (e.g. Brünn/Brno on map 2). We plan to bypass the disambiguation for a hand-picked list of places. As big datais an entanglement of implicit theoretical assumptions (Crawford et al., 2014), the difference between a mere data collection project and a digital humanities study resides precisely in the number and diversity of filters used. The code and listings produced for this study are available online. 5 We plan to integrate corpora of greater variety and scope and to include more specific metadata in order to design versatile visualizations.

6. Conclusion

A map is a discrimination, a marking of difference (Wulfman, 2014): our maps highlight the linguistic and cultural ties of Kraus and his contemporaries with Bohemia and Northern Italy, where there are more numerous toponyms to be found than in Hungary.Beyond that, "Die Fackel" is (at least) a European phenomenon; Kraus' vision of Europe is more inclined towards cultural centers (Prague, Munich, Paris, Berlin).

It is our hope that visualization studies based upon mixed methods contribute to a greater awareness of the potential of digital heritage as well as literary studies in the digital age. Although the maps seem immediately interpretable, they are not an objective result but a construct (Juvan, 2015), the result of a filtering. The "human" interventions on the map as well as the technical competence to do so replace this study in the hermeneutic circle of the philological tradition.

- AAC-FACKEL. Die Fackel. Herausgeber: Karl Kraus, Wien 1899-1936. In Biber, H., Breiteneder, E., Kabas, H., Mörth, K.; Graphic Design: Burdick, A.(eds), AAC Digital Edition 1, http://www.aac.ac.at/fackel.

- Biber, H. (2001). In Wien, in Prag und infolgedessen in Berlin - Ortskonstellationen in der "Fackel". In Marten-Finnis, S., Uecker, M. (ed.) Berlin-Wien-Prag. Moderne, Minderheiten und Migration in der Zwischenkriegszeit, Peter Lang, pp. 15-26.

- Crawford, K., Gray, M. and Miltner, K. (2014). Big Data | Critiquing Big Data: Politics, Ethics, Epistemology | Special Section Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 8: 1663–72.

- Hu, Y., Janowicz, K. and Prasad, S. (2014). Improving Wikipedia-Based Place Name Disambiguation in Short Texts Using Structured Data from Dbpedia. Proceedings of the 8th Workshop on Geographic Information Retrieval, ACM, pp. 8-16.

- Juvan, M. (2015). From Spatial Turn to GIS-Mapping of Literary Cultures. European Review 23(1): 81-96.

- Jurish, B. and Würzner, K.-M. (2013). Word and Sentence Tokenization with Hidden Markov Models. JLCL, 28(2): 61–83.

- Leidner, J. L. and Lieberman, M. D. (2011). Detecting Geographical References in the Form of Place Names and Associated Spatial Natural Language. SIGSPATIAL Special, 3(2): 5-11.

- Pouliquen, B., Kimler, M., Steinberger, R., Ignat, C., Oellinger, T., Blackler, K., Fluart, F., Zaghouani, W., Widiger, A., Forslund, A.-C. and Best, C. (2006). Geocoding multilingual texts: Recognition, disambiguation and visualisation. Proceedings of The Fifth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC), pp. 53-58.

- Sinnott, R. W. (1984). Virtues of the Haversine. Sky and Telescope 68(2): 159.

- Wulfman, C. E. (2014). The Plot of the Plot: Graphs and Visualizations. The Journal of Modern Periodical Studies, 5(1): 94-109.