Authors: Paul Atkinson, Ian Gregory, Catherine Porter

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: corpus linguistics, GIS, newspapers, infant mortality

Combining Corpora and Statistics using Geographical Technologies: New Evidence on Nineteenth Century Infant Mortality Decline in England and Wales

The division between quantitative and qualitative approaches is fundamental to the study of the past. Quantitative approaches are predominantly used to study statistical sources in fields such as historical demography and economic history where large numerical databases are available. These approaches are well suited to situations where large volumes of digital statistics are available and are very good at finding relationships between variables. They can be criticised on two levels: firstly, while good at identifying relationships they are poor at establishing the causal mechanisms that cause them. Secondly, and more fundamentally, most information about the past is not in numerical form and thus cannot form part of a traditional quantitative analysis, thus many relevant factors cannot be included within the analysis. Qualitative sources, particularly texts, are richer in both the range of material available and in the amount of detail it provides about the conditions in which people lived. They are however much more complex to work with and traditionally required close reading which is slow and selective. Digital technologies offer the potential to overcome this divide and make use of the combined advantages of both types of source, making use of statistical sources to identify patterns and relationships, and textual sources to help explain the patterns found. This paper presents an example of this based on infant mortality in Victorian and Edwardian England and Wales.

Infant mortality refers to deaths before the age of one, usually expressed as an infant mortality rate (IMR) of infant deaths per thousand births. An orthodox story is that infant mortality decline was brought about by government action on sanitation (Szreter, 1991; Woods et al., 1988; Woods and Shelton, 1997). More recently Gregory (2008) used a GIS database and demonstrated that infant mortality decline actually started before the Public Health Acts, that decline was earlier and steeper in rural areas of the south and east of England than anywhere else, and that rural parts of the north, Wales and the West Country had among the lowest rates of improvement. He was, however, unable to explain this variation with the data available. This paper uses a combination of statistical and textual sources to attempt to provide explanations for infant mortality decline with an emphasis on rural areas.

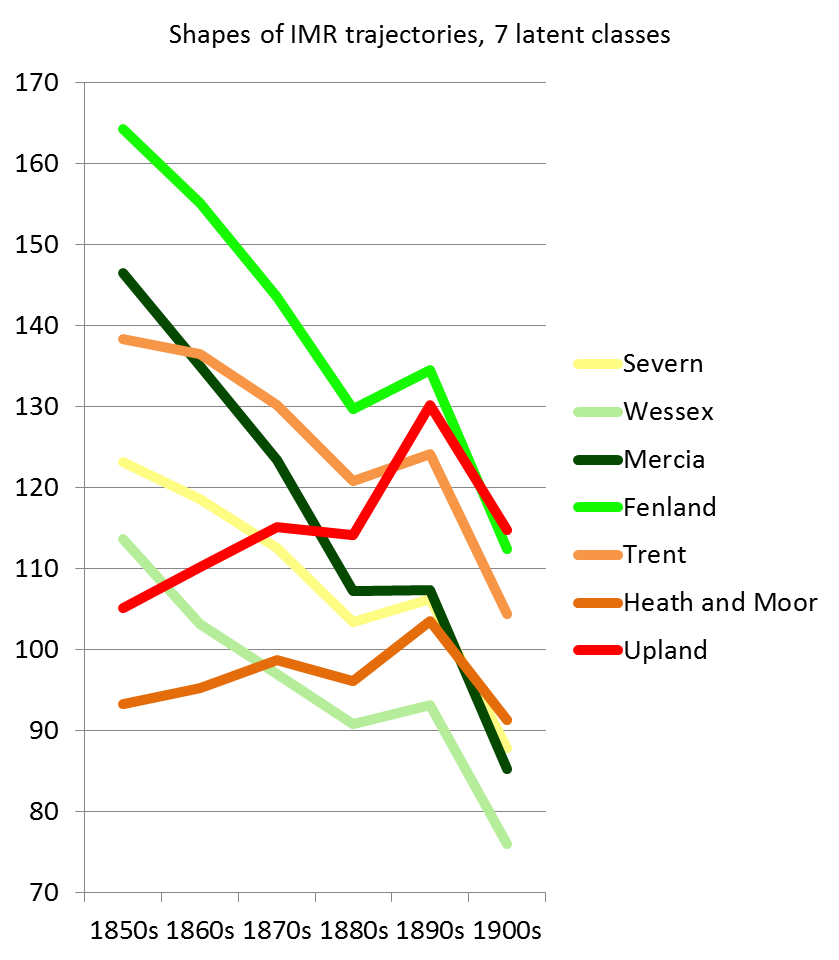

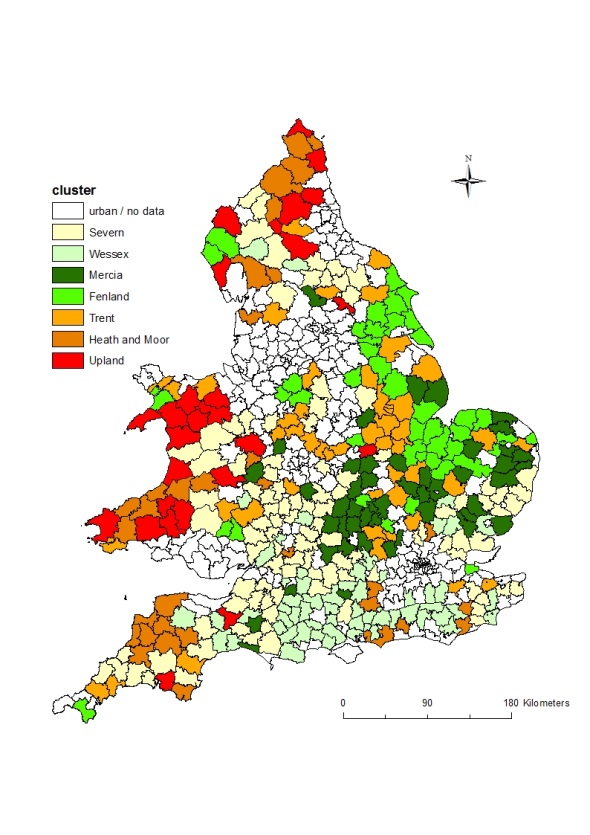

In the quantitative stage, as many geographically disaggregate independent variables as possible were assembled to explore what other factors seemed to be associated with infant mortality decline. Analysing change over time and space for multiple variables is difficult. A technique called Latent Trajectory Analysis to do this but combine it with the use of GIS (Nagin, 1999). Figure 1 shows how this techniques was used to group districts into seven clusters based on their temporal characteristics, and then map where rural districts with similar trajectories are found. This confirms that there was a clear geography to infant mortality decline. The biggest improvements occurred in rural areas in the south and east in the clusters described as ‘Fenland’ and ‘Mercia.’ Areas showing the lowest declines, which in some cases actually got worse, were in the north and west in the clusters described as ‘Upland’ and ‘Heath and Moor.’

Further analysis reveals statistically significant relationships between infant mortality change and rates of female TB and a less strong relationship with female literacy. These relationships have been shown elsewhere in the literature, however our findings show that these factors were important in rural areas as well as in urban ones. Interestingly convincing relationships could not be found with population density or fertility, these would be expected from the literature. The other striking finding was that the most important independent variable in every model was ‘decade’, in other words, change over time that none of our other variables could account for. Fundamentally this tells us three things: first that there are some very interesting geographical patterns to infant mortality decline, second that this is related to some other factors, particularly female health and education, and third that even though we have assembled what we believe to be as many quantitative independent variables as it is practical to use, these are unable to account for much of the change in infant mortality over this period.

The relative lack of explanatory ability by the quantitative analysis is hardly surprising given the lack of variables on a whole range of topics that may be associated with improving infant health, including: sanitary conditions, access to midwives and healthcare, attitudes towards breast-feeding, access to safe cows’ milk, and so on which have never been captured in statistical form. Thus, if we are going to improve our understanding we need to explore non-quantitative sources. Of particular interest here is the British Library’s Nineteenth Century Newspapers collection, a corpus of over 50 newspapers, most of which are available for series that cover most of the century. The corpus is at least 30 billion words although, to date we have been working with individual newspaper series which are usually hundreds of millions of words.

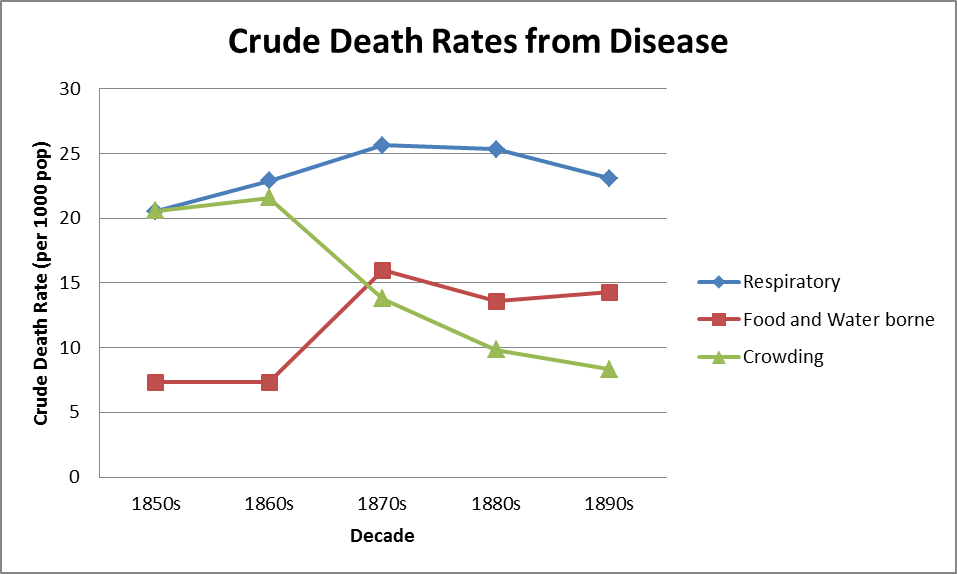

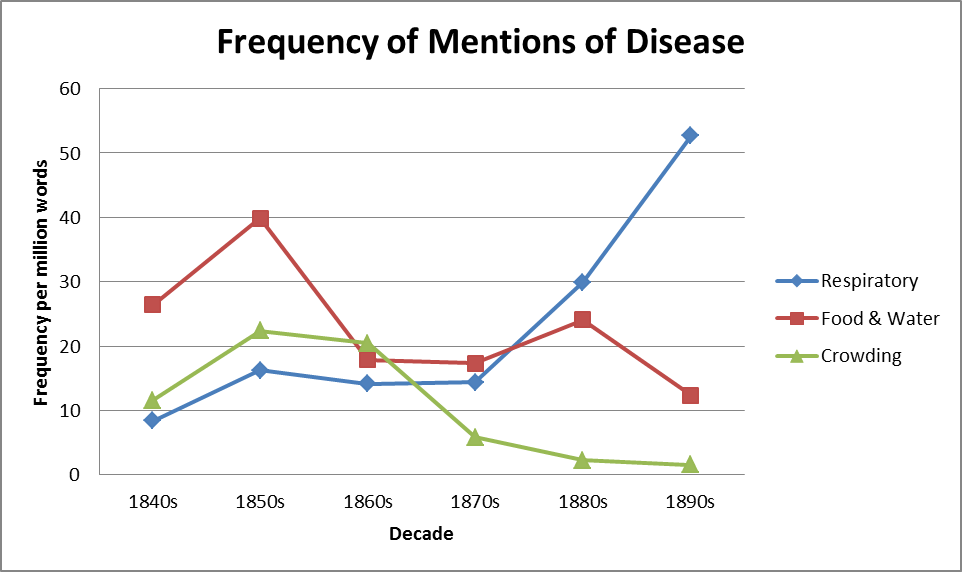

Figure 2 shows the use of one newspaper, the Era, to explore the relationship between interest in a variety of diseases associated with the young, classed according to whether they are respiratory diseases, food and water-bourn diseases, and diseases associated with crowding (Woods, 2000). The frequency with which these diseases are mentioned in the corpus is compared with the death rates from the diseases. Different disease types show quite different results. Interest in diseases of crowding follows the decline in these diseases, particularly associated with the decline of scarlet fever and typhus. Food and water death rates rise overall while interest in them seems to fall, while deaths from respiratory diseases are broadly flat but there is a major increase in interest in them in the 1880s and 1890s. We can then explore the collocates to these terms, the words that are found close to them. This shows four major classes of collocates: first, other words associated with disease, included other disease names, and words such as ‘died’, ‘attack’ and ‘epidemic.’ Second there are symptoms of disease, third are brand names of medicines typically found in advertisements, and fourth there are military terms which are found in the 1850s and are related to the Crimean War.

To allow us to explore the geographies within themes within the newspapers we have developed a technique we call concordance geoparsing (Rupp et. al., 2014). This involves firstly extracting concordance lines around the search-term. These concordance lines are then geo-parsed using the Edinburgh Geoparser (Grover et. al., 2010) which identifies place-names and matches them to a gazetteer to allocate them to a grid reference. The results are then explored to check for errors which are corrected with the corrections added to an updates file. In this way we can cumulatively remove geoparsing errors and have confidence in its results.

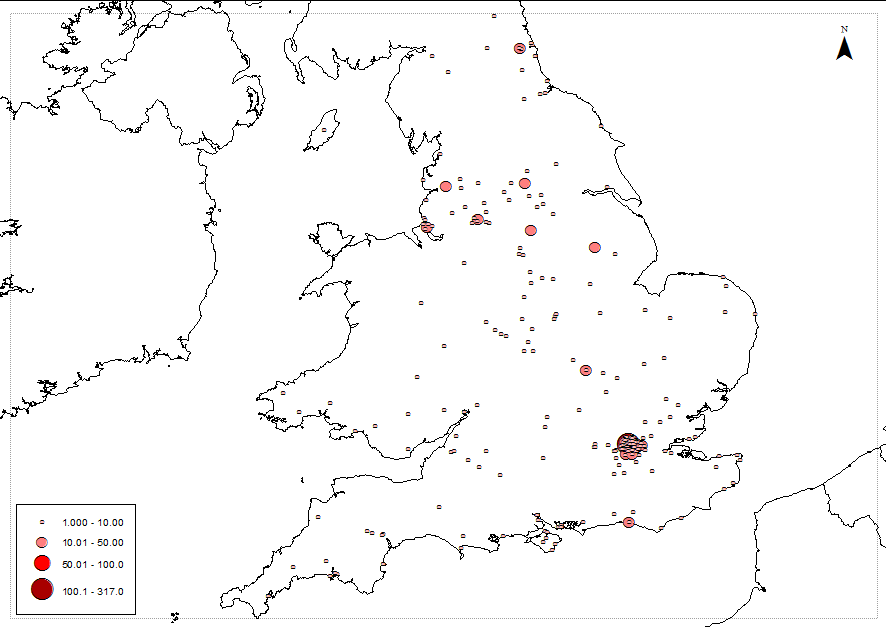

Figure 3 shows the place-names associated with the diseases in the Era. It is noticeable that these are concentrated in urban areas but there are exceptions to this. We will present comparisons between the number of references to a disease and the number of deaths from it in a district, showing how media interest was not related to disease severity.

Taking this work further, we will take regional newspapers from rural areas that experienced the highest and lowest declines and explore these for collocates and places that are associated with diseases themselves and a wide range of potential causal factors that may be related to them. In this way we will be combining the descriptive strengths of statistical data with the explanatory power of textual sources, using text to work around insufficiencies of data and making use of the temporal and geographical detail in both.

Acknowledgement: The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC grant “Spatial Humanities: Texts, GIS, places” (agreement number 283850).

- Gregory, I. N. (2008). Different places, different stories: Infant mortality decline in England and Wales. 1851-1911 Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98: 773-94.

- Grover, C., Tobin, R., Woollard, M., et al. (2010). Use of the Edinburgh geoparser for georeferencing digitized historical collections. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 368, pp. 3875-889.

- Nagin, D. S. (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semi-parametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods, 4: 139-57.

- Rupp C. J., Rayson P., Gregory I., et al. (2014). Dealing with heterogeneous big data when geoparsing historical corpora. Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Big Data, pp. 80-83.

- Szreter, S. (1991). The GRO and the Public-Health Movement in Britain, 1837-1914. Social History of Medicine, 4: 435-63.

- Woods, R. I. (2000). The demography of Victorian England and Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Woods, R. I., Watterson, P. A. and Woodward, J. H. (1988). The causes of rapid infant mortality decline in England and Wales, 1861-1921. Part I. Population Studies, 42: 343-66.

- Woods, R. I. and Shelton, N. (1997). Atlas of Victorian Mortality. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.