Authors: Silvia Piccini, Matteo Abrate, Clara Bacciu, Andrea Bellandi, Emiliano Giovannetti, Lorenzo Mancini, Andrea Marchetti

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: Ontologies, Information Visualization, Ontologies Visualization, Dynamic Knowledge, Literary Computing

When Traditional Ontologies are not Enough: Modelling and Visualizing Dynamic Ontologies in Semantic-Based Access to Texts

1. Introduction

The work described in this paper came about as a result of reflections made within the “Clavius on the web” Project1, which studied the correspondence between the Jesuit mathematician and also astronomer and some important scientists of his century, such as Galileo and Brahe2. One of the main aims of the project is to make it possible for students and scholars to access the texts on a semantic basis, in order to allow a deeper understanding of the often complex content, they convey.

Texts are often the unique source that scholars have at their disposal in order to be able to reconstruct and more completely understand the past author’s thought.

In order for technology to come to the aid of scholars in this effort, the concepts evoked within the text, as well as the terms representing these concepts need to 1) have a structured organization 2) be explicitly and univocally represented and 3) be defined through the relationships that unite them. In order to achieve this, we chose to adopt an ontologybased model, as ontologies are a de facto standard for knowledge representation.

Interestingly, the choice to use ontologies raised some issues, also with regard to theoretical aspects: indeed, standard ontological formalisms usually static and crisp proved to be inadequate in modelling the complexity of the knowledge conveyed by the analysed texts. As a result, more refined models as well as appropriate graphical representations needed to be introduced so that computers would be able to process these ontologies and visualize them in a way that students and scholars could understand and work with them.

2. The ontological model

Here we list and briefly describe the main aspects of the knowledge conveyed by the Clavius’ corpus that our ontological model should capture.

- Explicit versus implicit knowledge : our ontology is designed to structure both the entities explicitly evoked in the text (typically denoted by terms) and the entities implicitly entailed as belonging to the background knowledge that the writer implies (which can be possessed by the reader themselves only in part).

- Shared versus individual knowledge : different authors can share, and in fact do share, some aspects of conceptualising the domain, as clearly they have certain theories and beliefs in common. However, our ontology must formally structure the author’s own conceptualisation of the world, as it emerges from specific textual passages of the analysed corpus.

- Certain versus uncertain knowledge : in the case where the authors express confidence in some theories or reject and advance doubts towards others. It is therefore essential for each entity which populates the ontology (a class, an instance, a property) to be associated with a degree of certainty.

- S tatic versus dynamic knowledge : correspondence implies sharing information and knowledge, which can lead to changes in the way the correspondents view the world, sometimes significant. This is particularly the case with scholars. As a result, the ontology needs to be dynamic and temporal, so that it is possible to illustrate the evolution of the author’s conceptualization over a period of time. The specific time is either explicitly indicated by the author in his/her work or reconstructed from other sources.

Other parameters could be considered, such as vagueness, ambiguity and sincerity. The validity of these aspects is not limited to these kinds of texts (i.e. scientific letters), but it applies to any text such as essays, scientific journals, diaries, which expresses an author’s firmly-held or evolving opinion. Consequently, as a case study (see Section 4), we chose Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius(Galilei, 2001), to prove the applicability of the model outside the epistolary corpus. In the present paper, we will mainly focus on dynamic knowledge and its representation.

3. Models for representing dynamic knowledge

In literature, the problem of representing dynamically evolving information in ontologies has been addressed by adopting several different approaches (Flouris et al., 2008). A very simple solution is to create a version of the ontology for each temporal event that has to be represented (ontology versioning). However, a versioning algorithm is necessary in order to access the different temporal variants of the ontology. Other proposals aim to extend OWL ontologies in order to provide binary relation instances with a time reference. Related approaches are: (Welty et al., 2006) encoding a perdurantist/4D view in OWL, (Krieger, 2008) interpreting original entities as time slices, and (Manola et al., 2004) reifying original relations. For an exhaustive list of works, see (Krieger and Declerck, 2015). However, all of these approaches typically invalidate standard OWL reasoning, and they do not allow the representation of the change in subsumption and instantiation. In (Rizzolo et al., 2009) time semantics is added also to resources by providing temporalvarying classes and individuals, but only for RDF(S) ontologies, by extending the model presented in (Gutierrez et al., 2005). However, domain expertoriented tools for manipulating RDF(S) do not currently exist.

Against this background, we chose to conduct our first experiments with a reification-based approach and SKOS3 , the latter providing the best compromise between temporal aspects representation, availability of tools, querying and reasoning capabilities.

4. A case study

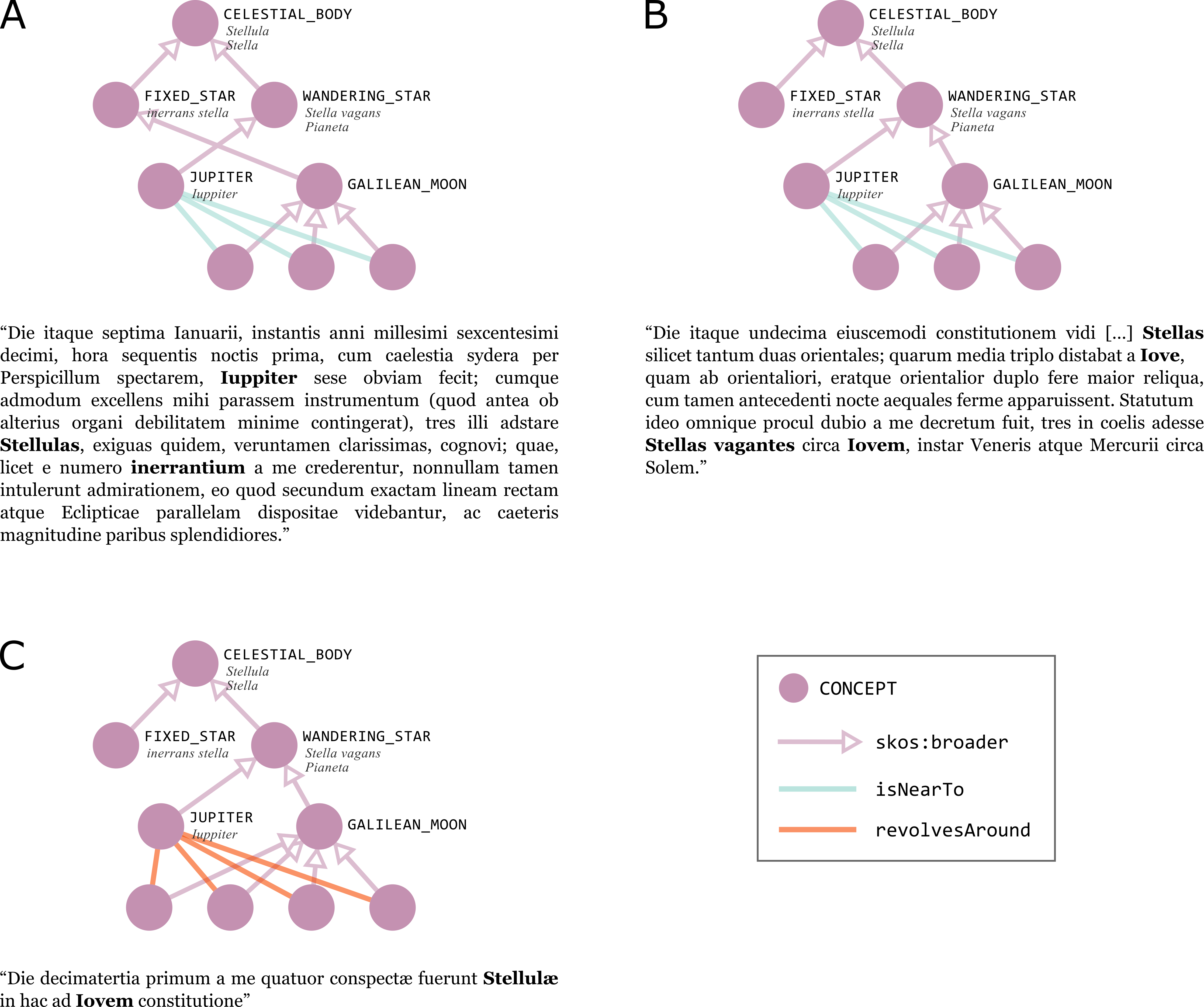

We propose here a possible representation of the evolution of Galileo’s conceptualization of Jupiter’s moons over a specific week in 1610, reconstructed on the basis of the Sidereus Nuncius.

The first observation of the planets dates back to 7th January 1610, when Galileo first saw what he thought were three fixed stars near Jupiter. After several observations on 11 th January, he noticed that their position relative to Jupiter changed in the same way as wandering stars. Two days later, he observed that there existed four satellites orbiting around Jupiter and not three.

Here we present the preliminary version of the ontology which structures the content of portions of the Sidereus Nuncius where Galileo describes his observation of Jupiter’s moons.

We first identified the key terms of the text as the terminology (in bold in Fig. 2) upon which we defined the explicit entities of the ontology. In addition we specified the necessary implicit entities to add to it (eg. Galilean moon). The ontology was built using Protégé 5.0.0 (Musen et al., 2000) and the plugins Skos Editor4 and Chronos (Preventis et al., 2014), the former to implement an SKOS ontology and the latter to add the diachronic component. The process is described in the following steps:

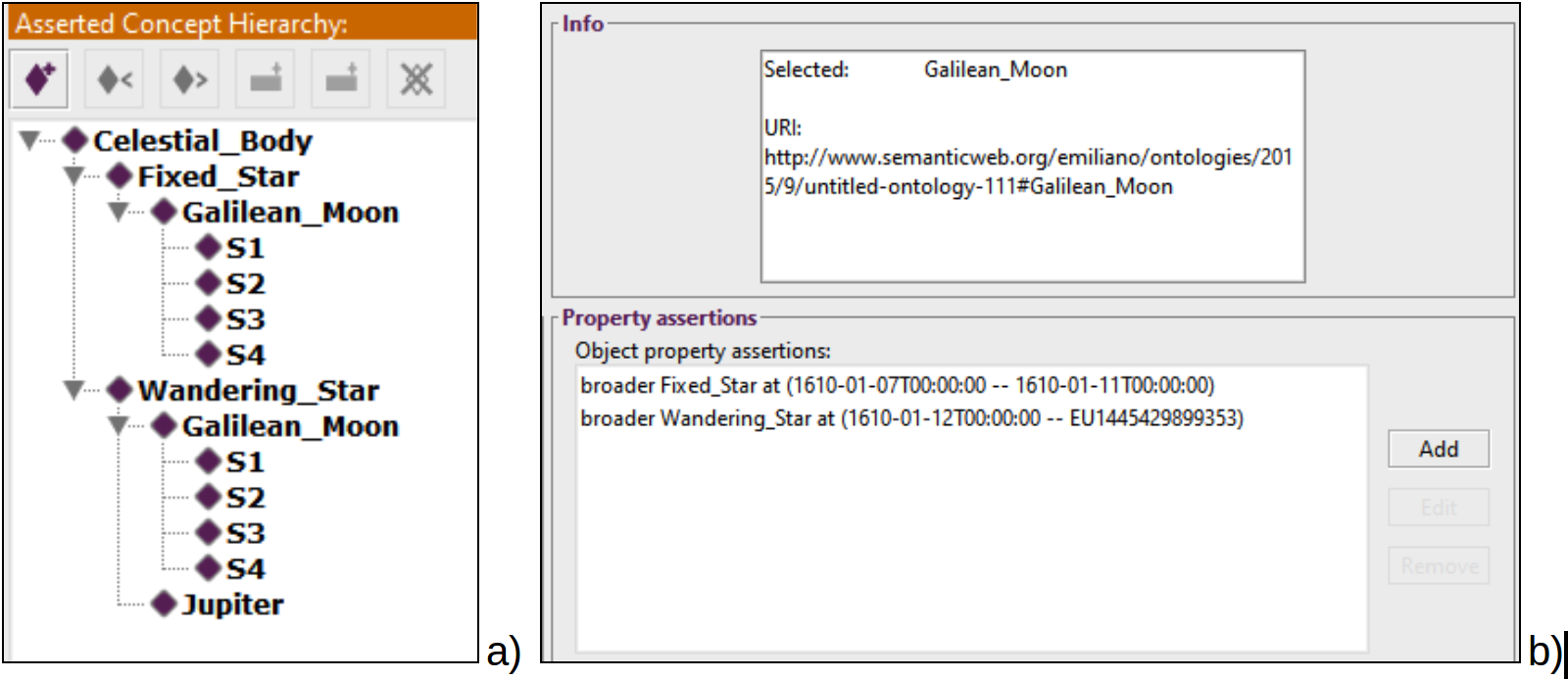

- Structuring of the concepts via the skos: broader relation; the concept Galilean_Moon has been set as a subconcept of both Fixed_Star and Wandering_Star (Fig. 1.a);

- Definition of the properties isNearTo and revolvesAround ;

- Instantiation of these two properties between the four moons (S1, S2, S3, and S4) and Jupiter;

- Conversion of the properties broader, isNearTo and revolvesAround into temporal;

- Attribution of the correct time interval to each property instantiation.

As a result of this representation, the concept Galilean_Moon became narrower than Fixed_Star during the time interval between 7th and 11th January 1610, then it changed to narrower than Wandering_Star (Fig. 1.b). Analogously, each of the three moons progressed from being simply “nearTo” Jupiter to “revolvesAround” Jupiter. Finally, starting from 13th January, the relation broader also links S4 and Galilean_Moon (i.e. Galileo spots a fourth object).

Browsing the constructed dynamic ontology allows to answer to complex queries such as: “how did Galileo’s vision of Jupiter’s moons evolve in time?” or “which had been Galileo’s main changes of perspective about Jupiter in January of 1610?”.

5. Visualization of the ontology

A visualization can be described as an artefact that helps humans to make decisions, learn and communicate, acting as a visual cognitive support (Card et al., 1999). A visual representation of ontologies can therefore be developed to ease their comprehension by both scholars and non-expert users. In our case, a suitable graphical display allows to make visual comparisons between the different time frames of a dynamic ontology, capturing the evolution of the author’s ideas. Among the available visualization techniques, we adopted the node-link diagram, which is particularly well suited for exploring the topology of a network and for locating paths (Munzner, 2014).

We wanted to automatically produce visualizations with a quality resembling that of hand-made diagrams (Dwyer et al., 2006; Kieffer et al., 2013). To do so, we observed the work of experts sketching some ontologies on paper, and derived a series of geometric constraints for an automatic placement algorithm. Since the skos:broader relationship defines a quasi-hierarchy, i.e., a tree with a reasonably small amount of nodes having multiple parents, the constraints we implemented were intended to produce a familiar, tree-like representation.

The input for the layout algorithm is the entire SKOS graph, and the output is a single layout for all the time frames. Comparison is then made possible by displaying a series of juxtaposed views, each showing only the items of a specific time frame (Fig. 2). This technique ensures that the same item is given the same position in each view, while differences create easy-to-spot “holes”', thus leveraging the user's spatial memory to carry out the comparison task (Munzner, 2014).

- Card, S. K., Mackinlay, J. D. and Shneiderman, B. (1999). Readings in Information Visualization: Using Vision to Think, Morgan Kaufmann.

- Dwyer, T., Koren, Y. and Marriott, K. (2006). IPSep-CoLa: An incremental procedure for separation constraint layout of graphs, Visualization and Computer Graphics, IEEE Transactions on, 12 (5):821–28.

- Flouris, G. et al. (2008). Ontology change: Classification and survey, The Knowledge Engineering Review, 23(2): 117–52.

- Galilei, G. (2001). Sidereus nuncius, Andra Battistini., Marsilio, Venezia.

- Gutierrez, C., Hurtado, C. and Vaisman, A. (2005), Temporal rdf The Semantic Web: Research and Applications, Springer, pp. 93–107.

- Kieffer, S. et al. (2013), Incremental grid-like layout using soft and hard constraints, Graph Drawing, Springer, pp. 448–59.

- Krieger, H.U. (2008). Where temporal description logics fail: Representing temporally-changing relationships, KI 2008: Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Springer, pp. 249–57.

- Krieger, H.-U. and Declerck, T. (2015). An OWL Ontology for Biographical Knowledge. Representing Time-Dependent Factual Knowledge, Proceedings of the First Conference on Biographical Data in a Digital World 2015, CEURS-WS.org.

- Manola, F., Miller, E. and McBride, B. (2004). RDF primer, W3C Recommendation, 10(1-107): 6.

- Munzner, T. (2014). Visualization Analysis and Design, CRC Press.

- Musen, M.A. et al. (2000). Component-based support for building knowledge-acquisition systems, Conference on Intelligent Information Processing (IIP 2000) of the International Federation for Information Processing World Computer Congress (WCC 2000), 194.

- Preventis, A., Petrakis, E.G. and Batsakis, S. (2014), CHRONOS Ed: a tool for handling temporal ontologies in protégé, International Journal on Artificial Intelligence Tools, 23(4): 1460018.

- Rizzolo, F. et al. (2009). Modeling concept evolution: a historical perspective, Conceptual Modeling-ER 2009, Springer, pp. 331–45.

- Welty, C., Fikes, R. and Makarios, S. (2006). A reusable ontology for fluents in OWL, FOIS, 150: 226–36.