Authors: Kevin Page, Terhi Nurmikko-Fuller, Carolin Rindfleisch, David Weigl

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: musicology, annotation, multimedia, performance studies

Digital Annotation Tooling for Opera Performance Studies

1. Background

In opera and music theatre, the realisation of a work in performance differs significantly from the abstract concept that is captured in the score. The scenic interpretation, with its own characteristics and specific perspective on the work, is created afresh in every new staging – thus a performance and its experience cannot be determined from the score alone (Cook, 2013).

Comparing a mere three stagings of Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen illustrates this point: the Bayreuth premiere in 1876, Boulez'/Cherau's "centennial Ring" in Bayreuth 1976, and the Ring Cycle in Birmingham in 2014 (which is the subject of our digital annotation capture in this paper). Not only are costumes and decorations entirely different, but also the setting and staging of the action, interpretation and presentation of the characters, visual and scenic aesthetics, and the perspective on and attitude towards the work.

For studies of the reception and perception of an operatic work, keeping a record of a particular performance – the characteristics of individual stagings – is an important requirement. This poses the question of how best to document the ephemeral phenomenon of an opera. Audio-visual recordings appear to provide an answer, but they are neither neither objective nor exhaustive; live annotation by a musicologist in the audience can thereby provide an additional or alternative resource.

2. Musical Score Annotation Kit

We developed the Musical Score Annotation Kit (MuSAK) to capture these musicological annotations, designing it to meet the requirements – and technical compromises – of operating in the environment and timescales of a live production in a working theatre, and providing an interface of sufficient responsiveness and adaptability to meet the needs of a working musicologist. The kit comprises:

- A touchscreen tablet device, running a bespoke web-based client through which each individual page of a score can be annotated and pages can be turned;

- A server based on the Union platform which gathers annotation keystrokes from the tablet client;

- A second "score following" page-turn annotation interface, capturing timings of the realisation (performance) of the material on a particular score page;

- A Livescribe Echo digital smart pen, used to take notes beyond those described in the annotation key (see below);

- Capture of audio and video, potentially recording both the staged performance and the musicologist using MuSAK.

Technical details of the MuSAK infrastructure are fully described elsewhere (Page et al., 2015). In this paper we report upon the utility of the toolkit: both in relation to the needs of the musicologist during the annotation event; and in relating the quantitative temporal data captured to the qualitative consideration of its potential musicological interpretation. Particularly with regard to the latter data-derived investigations, a key functionality of the kit for post-performance analysis is the temporal reconciling of the constituent digital media and annotations into a coherent metadata hyperstructure, enabling navigation of the information-dense digital captures (Nurmikko-Fuller et al., 2015).

3. Annotation workflow and enactment

The first full deployment of MuSAK captured annotations during a complete staging of Richard Wagner's Ring, performed on four nights over five days by the Mariinsky Opera at the Birmingham Hippodrome in November 2014 (Figure 1).

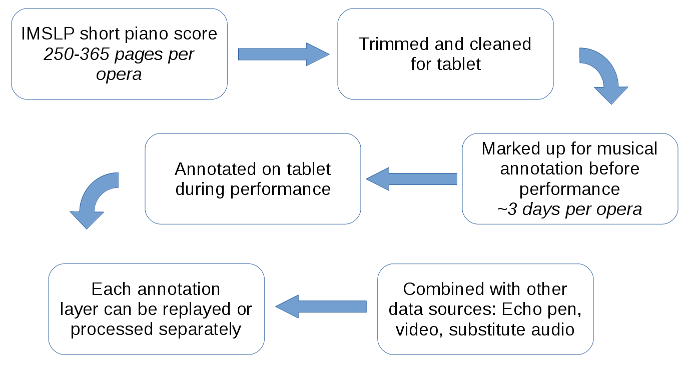

This multi-stage process is summarised in Figure 2. Digital images were generated from short piano scores of the operas obtained from IMSLP 1, then formatted and cleaned for viewing on the MuSAK tablet. The musicologist spent considerable time before the performance annotating printed copies of these scores which were subsequently re-digitised. These pre-performance notes highlighted musical elements determined directly from the score; these also served as "signposts" for potential points of interest which would be revisited during the live performance.

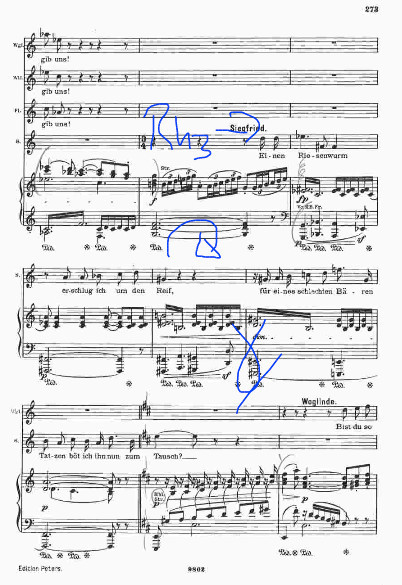

This necessitated the development of a symbolic key (Figure 3) which allowed annotations to be made at sufficient speed during the live performance, and which was trialled before deployment during co-development of the technical system. During the Birmingham staging the musicologist annotated the tablet-based score image directly using a stylus to draw symbols from the key (Figure 4), allowing for adaptation of the key between the nightly performances, based on experience during fieldwork.

A significant volume of annotation and related data was gathered: 15 hours of video footage; over 100,000 tablet strokes encoding 8,216 annotations; 1,300 performance based page turns; 1,316 digital score images; and 104 pages of writing producing 13 hours of digital pen replay.

4. Toolkit Assessment

The usability attributes of MuSAK were assessed in interviews with the musicologist after the Birmingham performances according to learnability, efficiency, memorability, and satisfaction, as defined by Ferre (Ferre et al., 2001).

Learnability was evaluated through the musicologist’s experience of acquiring the skills necessary to complete the annotation process. She found the system comparable to existing musicological annotation pragmatics, minimising the need for training:

Using MuSAK [is] very similar to the process that I as a musicologist used to do regularly...I think it worked very well because [it repeated existing] processes [...and] fitted in with actions I was very well adapted to...the tools were very non-invasive.

On satisfactory functionality and performance, the musicologist felt “quite” able to keep up with the pace of the opera, although believed that the time necessary to make additional freehand annotations and cognitively process observations made the page turn annotations inaccurate:

I was quite well able to keep up with the pace... I have been able to capture...a pretty good picture of...the profile of the performance... an important realisation is that making these scenic [and musical] annotations … which are particular about this performance... requires a lot of time to think and... process even if it is only [around] 10 seconds or 5 seconds...if we want to also capture a detailed and accurate time profile of the performance it would be necessary to have two people…

However, an analysis of the page turn data (below) indicates an ability to at least turn pages at a pace highly correlated with the performance. (MuSAK can also be configured to support multiple annotation devices and annotators simultaneously, although this was not done during the Ring capture.)

The musicologist reported an ability to capture the idiosyncratic profile of each specific performance, including deviations from the score or expectations based on it, as well as staging, lighting, and the behaviour of the actors:

...the performance details: are the musical details particular in any places, is something particular loud ...[or]... fast, are any mistakes made ... scenic specifics of the performance, what happens on stage... are people moving a lot, are they using a lot of gestures, are there significant lighting changes, are there changes of scenes...

MuSAK was described as supportive of traditional annotation paradigms, because new skills were not necessary for effective and efficient annotation using the touchpad screen and stylus:

...intuitive to use because it was mainly very similar to just using pen and paper which everyone who is concerned with analysing music is very used to... so it's very similar to the process that I as a musicologist used to do regularly anyway and ... it worked very well because it took up processes that were there anyway and tried to fit in with actions I was very well adapted to [...] very similar to [...] if you eventually get used to the touch screen which didn’t take such a long time...

The additional affordances of a digital system were noted, including the automatic capture of the temporal profile of the performance and the benefit of being able to easily make corrections:

...they actually help because with using a pen and paper you wouldn’t be able to undo things if you make mistakes, ...[nor]... be able to afterwards see the timings [...] with pen and paper doesn’t give such an accurate profile of this particular performance [...] you’re capturing the timings [of] not only the music but also the timings of the annotations because afterwards you can look at how dense are the annotations.

5. Data Interpretation

In addition to recording the musicologist’s (subjective) annotations, MuSAK can be used to produce statistics about the acts of annotation to supplement our understanding of the technical system and our interpretation of the musicological context.

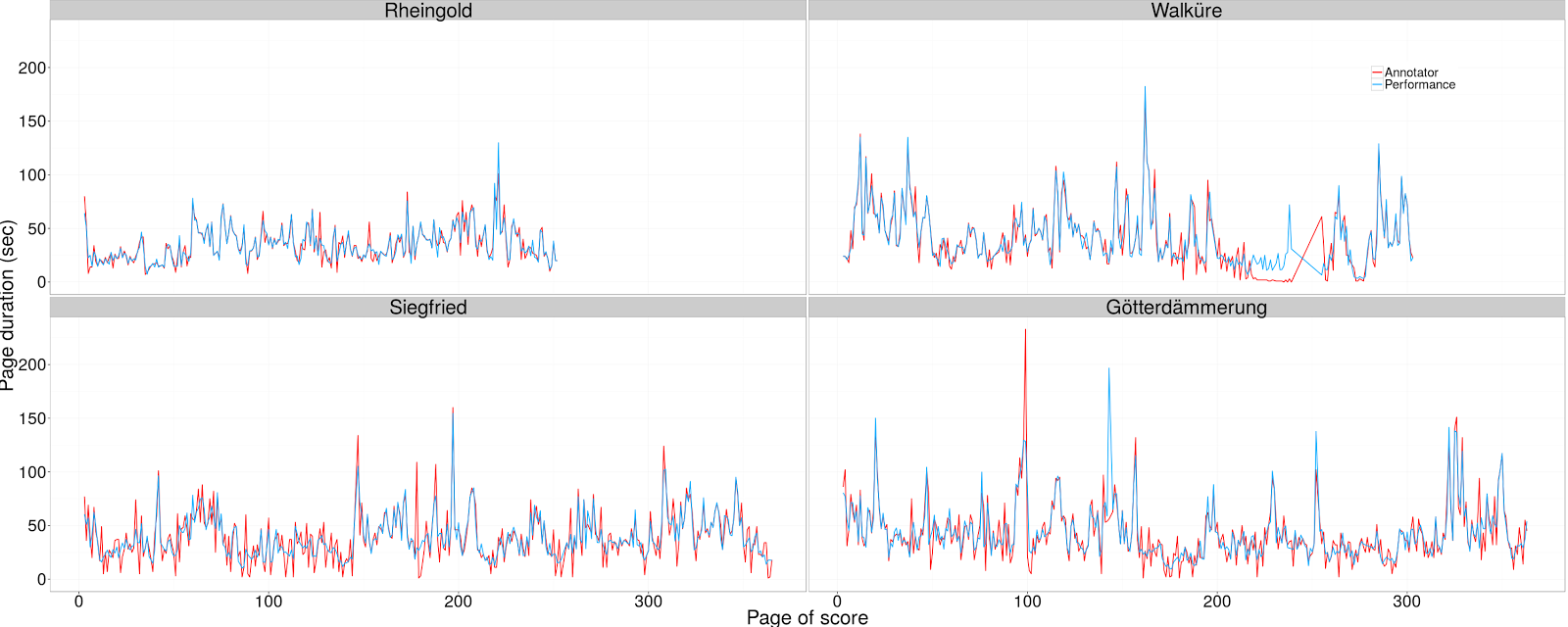

For example, Figure 5 shows comparative plots of what is, effectively, the rate of performance of each page (from the score-following annotations) compared to the musicologist, indicating an overall ability to "keep up" with the pace of the staging.

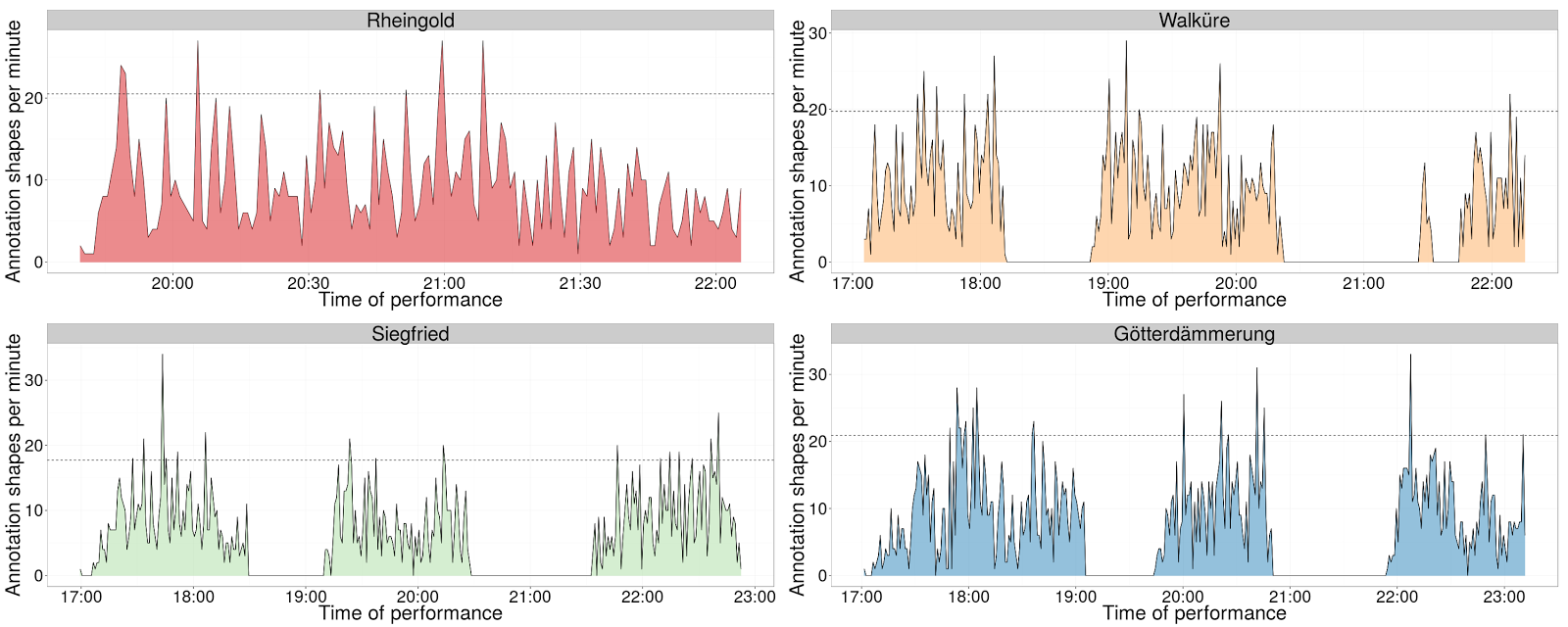

Figure 6 shows the rate of annotations over the course of the four operas, indicating what might be considered as a crude measure of "music information density".

Moments which pass a higher threshold of annotation rate have been identified to relate to significant music-dramatic instances in several places, which involve highly concentrated activity on stage (e.g. Hagen killing Gunther in Götterdämmerung).

- Cook, N. (2013). Beyond the Score: Music as Performance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ferre, X., Juristo, N., Windl, H. and L. Constantine, L. (2001). Usability basics for software developers, IEEE Software, 18(1): 22–29.

- Nurmikko-Fuller, T., Weigl, D. M. and Page, K. R. On organising multimedia performance corpora for musicological study using Linked Data. Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Digital Libraries for Musicology.Knoxville: ACM, pp. 25-28.

- Page, K., Nurmikko-Fuller, T., Rindfleisch, C., Weigl, D. M., Lewis, R., Dreyfus, L. and De Roure, D. (2015). A Toolkit for Live Annotation of Opera Performance: Experiences Capturing Wagner's Ring Cycle. Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval 2015. Malaga: ISMIR, pp. 211-17.