Authors: Simon Musgrave, Nick Thieberger

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: language documentation, digital infrastructrure, archiving, scholarly practice

If You Build It Will They Come? Digital Infrastructure And Disciplinary Practice In Language Documentation

Digital scholarship depends on the availability of data in forms which are tractable to computational techniques, implying storage of data in sustainable archives. This is perhaps even more true of research in the humanities than in science. As the ESF observed in their 2011 report on research infrastructure: “in the hard sciences, datasets tend to be generated rather than collected and tend to be homogeneous in nature …. In Humanities, data tends to be collected and to be heterogeneous in content and format” (European Science Foundation, 2011:5). It is both the possibility of storing the data and the stored data itself which makes up critical infrastructure in many disciplines and innovative scholarly practices may not develop in the absence of such infrastructure. Here, we discuss the development of digital infrastructure in the field of language documentation (within the discipline of linguistics) and try to assess the extent to which the provision of well-funded (by the standards of the discipline) infrastructure is changing scholarly practice.

Language documentation as a field in linguistics dates from the publication of the seminal paper ‘Documentary and descriptive linguistics’ (Himmelmann, 1998). It is in large part a reaction by linguists to the challenge of language endangerment (see Hale et al., 1992; and Musgrave, 2015 for a recent survey) and it emphasises the collection of large bodies of data of languages in use. Language documentation began at the same time that it was becoming feasible to make high quality digital recordings, both audio and video, on reasonably priced equipment. Archiving of documentary material was a core component of the program as conceived by Himmelmann, and this was immediately seen to mean digital archiving. Indeed, it can be argued that the whole enterprise of documentary linguistics falls comfortably within the digital humanities (Thieberger, 2014).

Two projects began in the first decade of the century to fund researchers to make collections of documentary materials. One was based at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) and funded by the Volkswagen Stiftung; 1 the other was based at the School of Oriental and African Studies (London, UK), funded by Arcadia. 2 MPI Nijmegen had a well-resourced technical department which took responsibility for developing the archiving stream of the DoBeS project. HRELP had to build their archive from scratch; no existing resources at SOAS were available to support their work. For both projects, it was a requirement of funded research that data were deposited in the relevant archive. Both archives, however, are open to deposits from non-funded researchers.

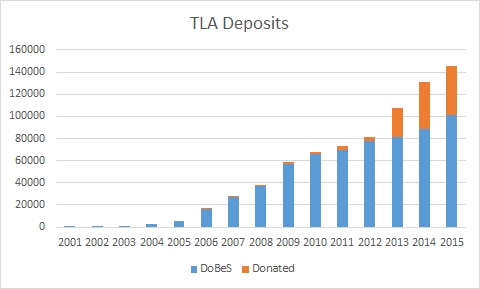

The DoBeS archive is subsumed under a larger archive called The Language Archive 3 which also holds language data from other MPI activities and from other institutions and projects. Figure 1 shows the cumulative deposits in TLA for DoBeS material and for material classified as donated. The figures here represent the number of files retrieved from the catalogue based on their ’Last modified’ field. This does not reflect the accession date of the file in all cases, but it is a reasonable proxy. 4

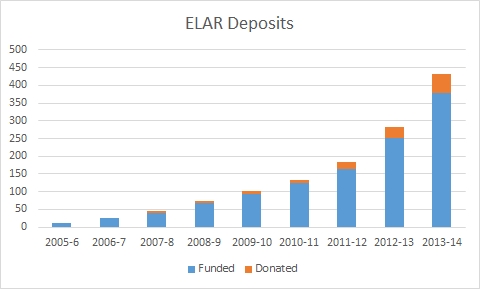

The archive at SOAS is known as ELAR. Figure 2 shows cumulative deposits in that archive; figures are drawn from information provided by ELAR in the annual reports of HRELP and represent bundles of data deposited rather than individual data files.

Although both archives have grown over the periods shown, the patterns are different, with a flattening out in the DoBeS deposits starting around 2011. There was no funding round in 2010. Projects were funded in 2011 and 2012 but 2012 was the final round and while the archive still expects to receive deposits from the last two funding rounds, such deposits will continue to decrease.

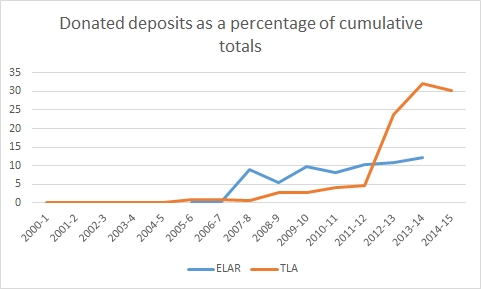

Figure 3 shows the percentage of donated deposits based on the cumulative figures for each archive.

For both archives, once the infrastructure was established, non-funded deposits make up an increasing proportion of the archive. TLA has added large amounts of donated material in recent years, in part a conscious effort by the archive to expand its activities beyond the DoBeS project by taking responsibility for existing data sets. One barrier to archiving data is meeting an archive’s requirements particularly in the area of metadata. ELAR uses a more flexible metadata system than TLA (which uses the IMDI scheme, https://tla.mpi.nl/imdi-metadata/). We might therefore expect more voluntary deposits in ELAR than in TLA, but this is not the case in these data. The different proxies we are using to assess these trends here make it difficult to compare the two exactly, but we can see a clear trend over the last decade which suggests that archiving data is increasingly a part of scholarly practice in this area of linguistics and that there has been progress since the rather gloomy summary provided by Thieberger (2011).

One question raised by this data is the extent to which the donated data is coming from researchers who have also been funded by the relevant program. Both projects provide training to funded researchers and it is possible that the practices learned there are continued when researchers collect data in other projects. In the case of TLA, 36 data sets have been deposited which were not the result of DoBeS funding and in six cases the researcher(s) had been funded by DoBeS for other work. ELAR has material not associated with funded projects deposited by 37 researchers of whom eight had been funded by ELDP for other work. These figures suggest that acquiring experience of the archiving process is a factor in future work practices, and that this factor has had very similar levels of effect in both archives.

The data which we have used in this paper are limited and important questions remain unanswered. The most obvious is how and to what extent are these resources being used. ELAR provide some usage statistics; based on logs for the month of November 2013, estimated traffic on the catalogue and the archive portal is around 680 users per day with an estimated 1.66 million pages served per year. These numbers suggest that the archive is being used a lot, but it is not possible to tell who the users are or what they are doing on the site. More fine-grained data are needed to tell us whether the availability of resources such as ELAR and TLA is changing scholarly practice in accessing language data.

The data we present here indicates that, in the field of documentary linguistics, the availability of good infrastructure for digital archiving has had an impact on scholarship. Data is being deposited in the archives beyond the requirements of the relevant funding bodies, and in the case of the archive for which usage statistics are available, it seems that the level of activity is substantial. These changes may in part be due to the level of training provided to funded researchers; but such training should, we suggest, be considered an essential part of the research infrastructure of digital scholarship. Another reason for the changes may be that linguistic scholarship is moving towards recognising primary data as scholarly output (Thieberger et al., 2016). This process is only possible when primary data can be cited using persistent identifiers provided by a repository (cf. NSF (Task Force on Data Policies), 2011:9 (Recommendation 2)). There is therefore the possibility of a virtuous circle here: adoption of best practice in data management will lead to more robust research methods in the field as well as career benefits for researchers.

- European Science Foundation (2011). Research Infrastructures in the Digital Humanities. (Science Policy Briefing). Strasbourg: European Sceince Foundation http://www.esf.org/fileadmin/Public_documents/Publications/spb42_RI_DigitalHumanities.pdf (accessed 2 March 2015).

- Hale, K., Krauss, M., Watahomigie, L. J., Yamamoto, A. Y., Craig, C., Jeanne, L. M. and England, N. C. (1992). Endangered languages. Language, pp. 1–42.

- Himmelmann, N. (1998). Documentary and descriptive linguistics. Linguistics, 36(1): 161–96.

- Musgrave, S. (2015). Endangered languages. In Allan, K. (ed), The Routledge Handbook of Linguistics. (Routledge Handbooks in Linguistics). Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 385–400.

- NSF (Task Force on Data Policies) (2011). Digital Research Data Sharing and Management. Washington DC: National Science Foundation.

- Thieberger, N. (2011). Where are the records? Endangered Languages and Cultures. http://www.paradisec.org.au/blog/2011/06/5649/ (accessed 1 November 2015).

- Thieberger, N. (2014). Digital humanities and language documentation. In Gawne, L. and Vaughan, J. (eds), Selected Papers from the 44th Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society, 2013. Melbourne: University of Melbourne, pp. 144–59. http://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/40961 (accessed 30 October 2015).

- Thieberger, N., Margetts, A., Morey, S. and Musgrave, S. (2016). Assessing Annotated Corpora as Research Output. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 36(1): 1–21. doi:10.1080/07268602.2016.1109428.