Authors: Michael Gregory Falk

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: Amelia Opie, Adeline Mowbray, Topic Modelling, Close Reading, Novels

Faraway, So Close!: Reading Adeline Mowbray Closely Using Topic Modelling

1. 1. Introduction: The “reading” debate

Digital humanists disagree fervently about the nature of reading, and how computers can change the way we do it. Some advocate “distant reading” as a radically new form of inquiry (Burdick et al., 2012, Jockers, 2013, Moretti, 2013). Others argue that computers can improve and enrich traditional modes of reading (Burrows, 1987, McGann, 2001, Ramsay, 2005, Ramsay, 2011). McCarty subsumes this debate in his third way of “interactive modelling” (2005). Pasanek, meanwhile, offers a whimsical alternative with his “desultory reading” (2015).

The hot polemic of this debate obscures a fundamental point: all these kinds of reading are deeply intertwined, and none should be treated as an exclusive option.

To demonstrate this, I apply a classic distant reading technique, topic modelling, to a corpus of texts, in order to assist in my close reading of a single novel, Amelia Opie’s Adeline Mowbray (1804). This is a good novel to test new methods on, because it poses stark interpretive problems. Its heroine is a radical who dies repenting her earlier beliefs: are we supposed to admire or condemn her? For two centuries, readers have disagreed, some finding the novel conservative (Tomalin, 1974; Butler, 1987), others radical (Kelly, 1981; King, 2009)—its original readers were mostly just confused (Cooper, 2001). If digital reading can help us answer this question, then we will learn more about the nature and use of digital reading itself.

2. 2. Methods

2.1. Software. I used the popular mallet package to perform Latent Dirichlet Allocation on Adeline Mowbray and 55 other realist novels from the period 1776-1822 (Mccallum, 2002). Blei and Jockers describe the method comprehensively (Blei, 2012, Jockers, 2014).

2.2. Corpus construction. A comprehensive selection of similar contemporary novels was taken from high-quality online archives.

2.3. Data preparation. Scholars disagree about how texts should be prepared for modelling: should they be chunked by paragraph (Algee-Hewitt et al., 2015), or by x-length chunk (Jockers, 2013, Jockers and Mimno, 2013, Jockers, 2014)? X-length chunks make it easier to include dialogue in the analysis, so these were preferred. The length was set at 125 words, any longer made close reading of the chunks harder; any shorter made the “topics” incoherent.

2.4. Parameters. I used hyperparameter optimization and Jockers’ stopword list; excluded characters’ names from the analysis; and set the number of topics at 150, avoiding the problems of incoherent and “chimera” topics identified by Schmidt (2012).

3. 3. Discussion and Results

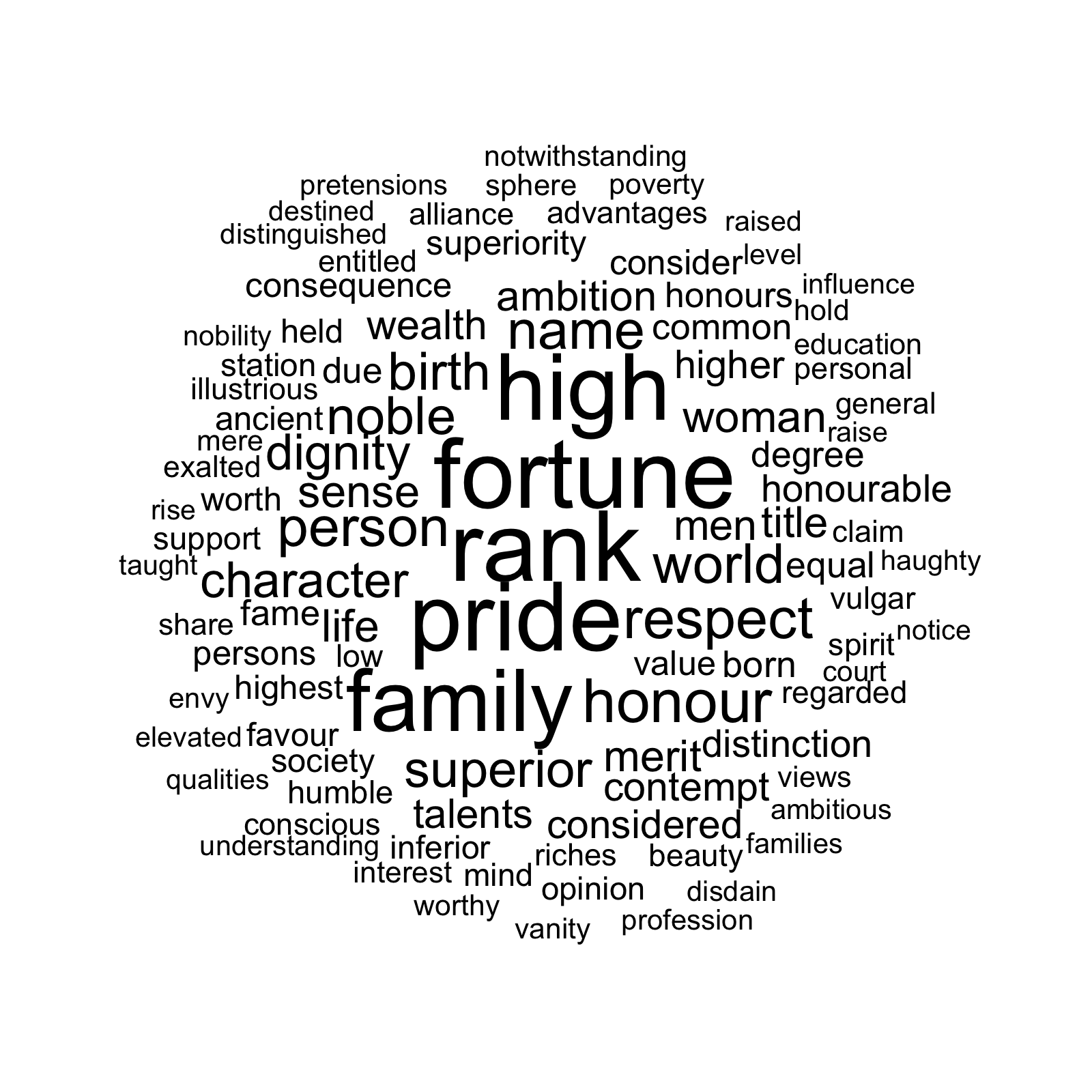

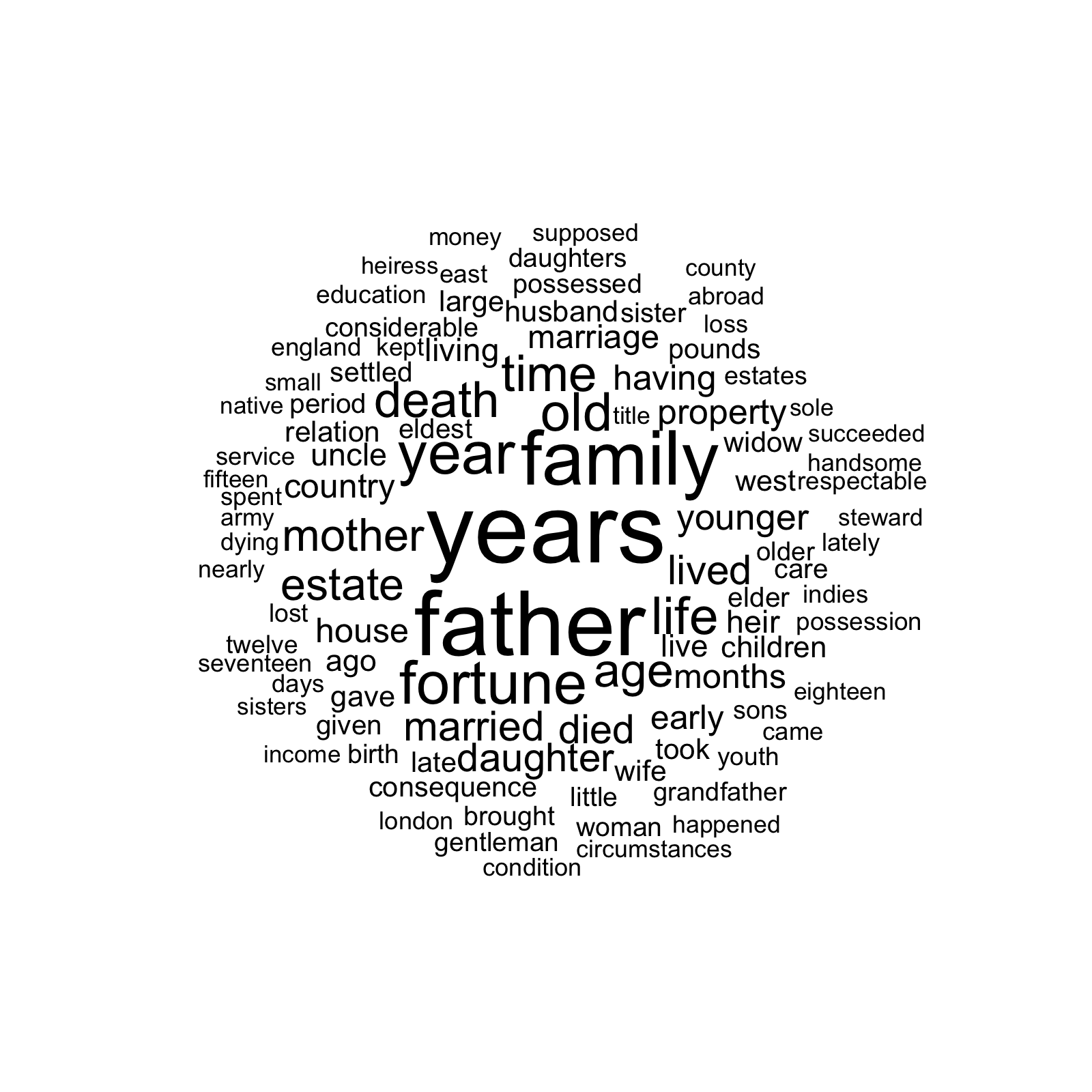

Applying this technique to the novels in my corpus produced two main kinds of results. First, the model identifies key “topics” in the corpus:

Such topics uncover hidden patterns between words in the corpus: for instance, the prominence of the words “year” and “years” in the discussion of a family’s marital history in novels of this period.

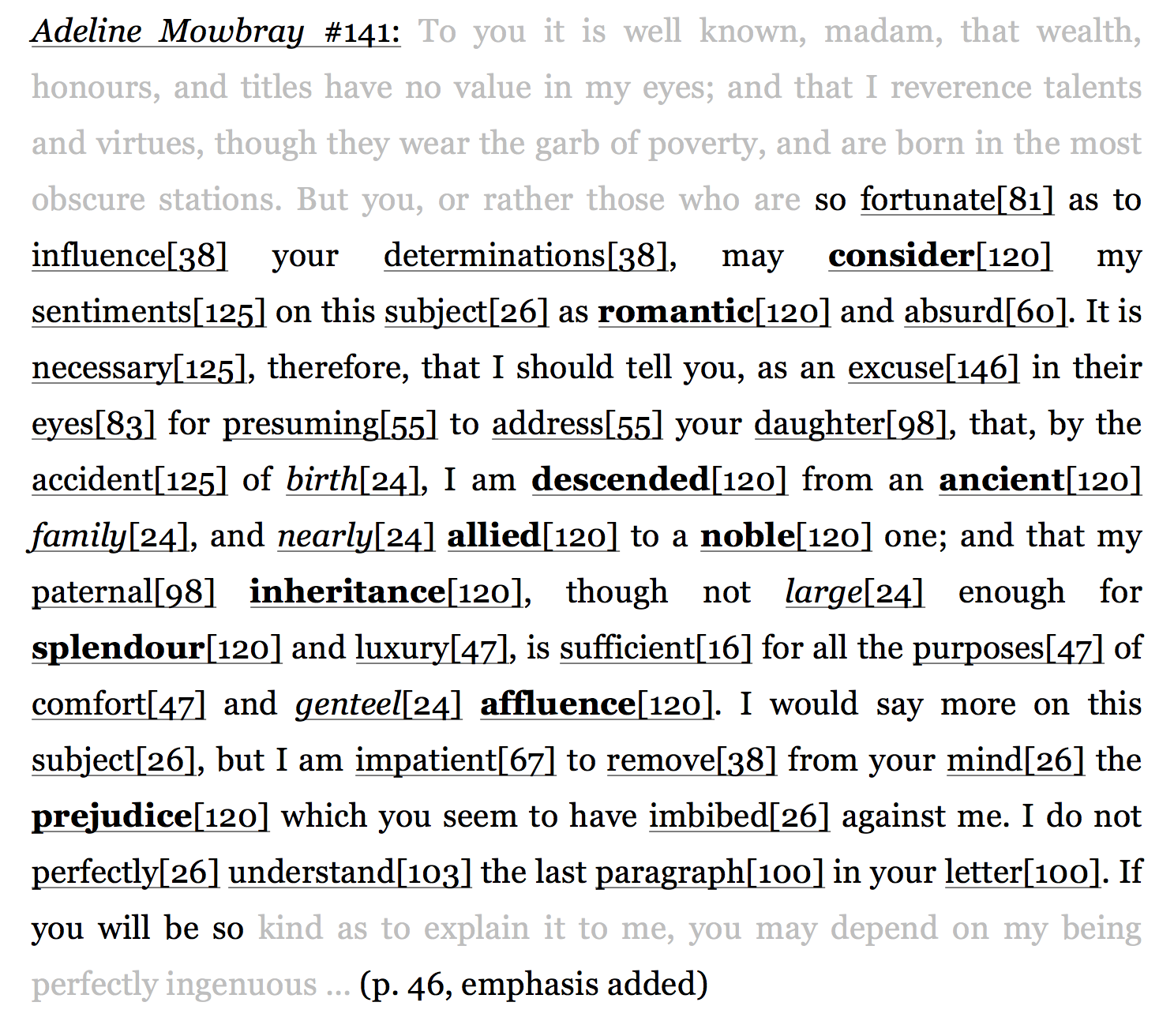

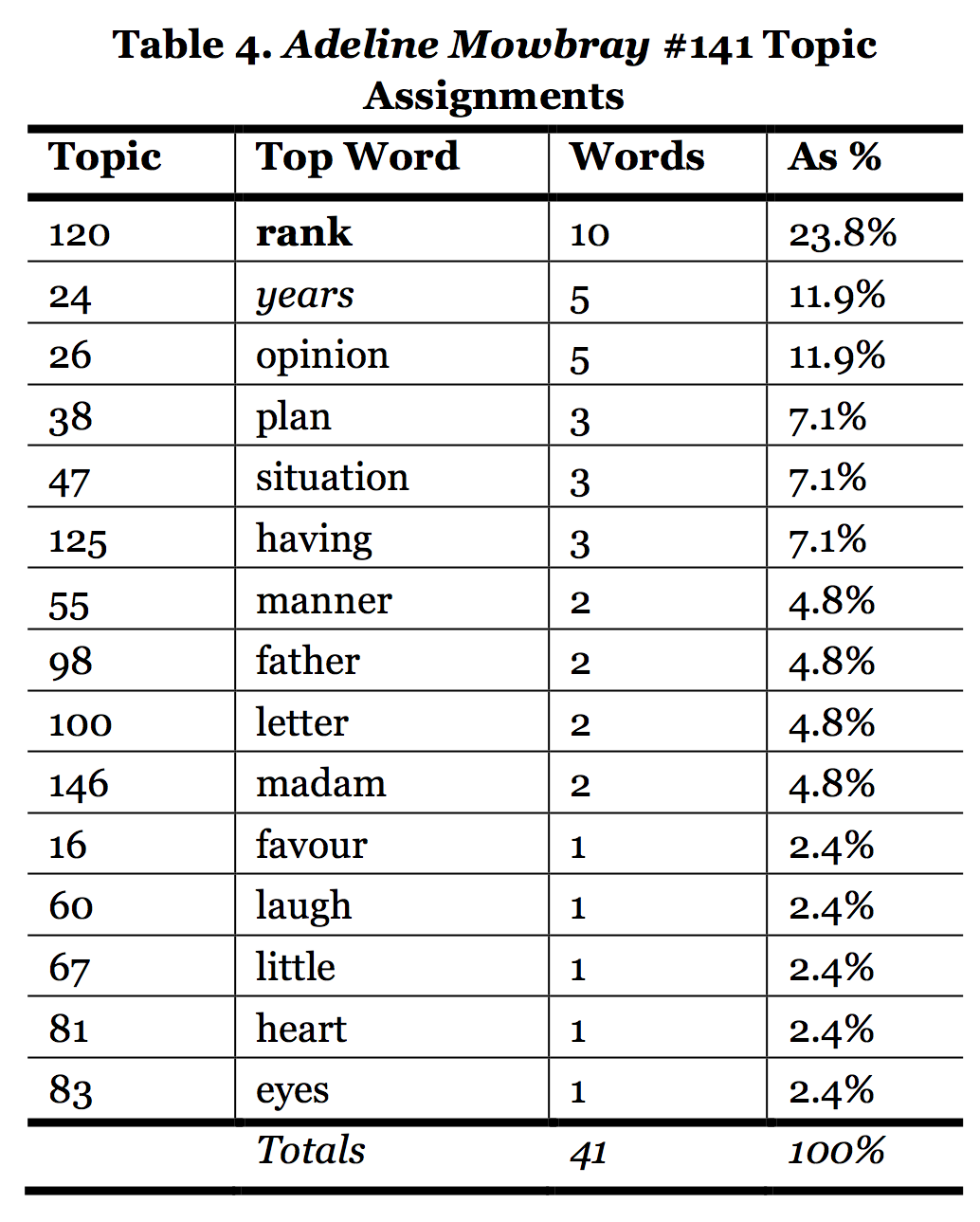

Secondly, as Rhody (2012) has shown, topic modelling enables us to visualise the linguistic composition of a passage:

Such visualisation is an invaluable tool of discovery, directing the scholar’s eye to significant patterns in a text’s language. In this case, the prominence of topics 120 and 24 in the passage turned out to be crucial.

In this passage, Glenmurray uses these topics to persuade Adeline’s mother that he is a good suitor. He is a radical who has published philosophical tracts against marriage. If the novel presents him as the ideal suitor for Adeline’s hand, we may assume that the novel itself has radical sympathies. As close reading reveals, topics 120 and 24 are often used to describe past or potential suitors, in both this and other novels from the corpus. In Adeline Mowbray, the language of these topics is used to describe many characters negatively, and only one positively—Glenmurray. This is compelling new evidence that he is the ideal suitor, and that the novel therefore portrays him and his radicalism sympathetically.

This reading was both “close” and “distant.” The reading was “distant” because it involved statistical analysis of 65,000 125-word chunks. But these patterns observed from a distance were used to unravel the complexities of a closely-read text. Close reading reveals strengths and flaws of the distant reading tool: it turns out that LDA assigns words to topics differently each time it is run, and is scuppered by novelists who write idiomatically. Close and distant reading, it seems, are so closely bound together that they are part of a single process. Their messy, unpredictable connections suggest a new kind of readerly ideal for the Digital Humanities: anarchic reading.

- Algee-Hewitt, M., Heuser, R. and Moretti, F. (2015). Paragraphs: The Forgotten Middle. Micromégas: The Very Small, the Very Large, and The Object of Digital Humanities. Stanford, CA.

- Blei, D. M. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM, 55: 77-84.

- Burdick, A., Drucker, J., Lunenfeld, P., Presner, T. S. and Schnapp, J. (2012). Digital_Humanities. Cambridge, MA and London, MIT Press.

- Burrows, J. F. (1987). Computation into Criticism: A Study of Jane Austen's Novels and an Experiment in Criticism. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Butler, M. (1987). Jane Austen and the War of Ideas. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Cooper, C. M. (2001). Reading otherwise: The abortive politics of Adeline Mowbray, or the mother and daughter. European Romantic Review, 12: 1-42.

- Jockers, M. (2013). Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. Urbana, Chicago and Springfield, University of Illinois Press.

- Jockers, M. (2014). Text Analysis with R for Students of Literature. Cham, Springer.

- Jockers, M. L. and Mimno, D. (2013). Significant themes in 19th-century literature. Poetics, 41: 750-769.

- Kelly, G. (1981). Amelia Opie, Lady Caroline Lamb, and Maria Edgeworth: Official and Unofficial Ideology. Ariel. A Review of International English Literature Calgary, 12: 3-24.

- King, S. (2009). The 'Double Sense' of Honor: Revising Gendered Social Codes in Amelia Opie's Adeline Mowbray. In: Wallace, M. L. (ed.), Enlightening Romanticism, Romancing the Enlightenment: British Novels from 1750 to 1832. Surrey, England: Ashgate.

- McCallum, A. (2002). MALLET: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit.

- McCarty, W. (2005). Humanities Computing. Houndmills, Palgrave.

- McGann, J. J. (2001). Radiant Textuality: Literature After the World Wide Web. Houndmills, Palgrave.

- Moretti, F. (2013). Distant Reading. London and New York, Verso.

- Pasanek, B. (2015). Metaphors of Mind: An Eighteenth-Century Dictionary. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Ramsay, S. (2005). In Praise of Pattern. TEXT Technology, 2: 177-90.

- Ramsay, S. (2011). Reading Machines: Towards and Algorithmic Criticism. Urbana, Chicago and Springfield, University of Illinois Press.

- Rhody, L. M. (2012). Topic Modelling and Figurative Language. Journal of Digital Humanities [Online], 2. Available: http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-1/topic-modeling-and-figurative-language-by-lisa-m-rhody/.

- Schmidt, B. M. (2012). Words Alone: Dismantling Topic Models in the Humanities. Journal of Digital Humanities [Online], 2. Available: http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-1/words-alone-by-benjamin-m-schmidt/.

- Tomalin, C. (1974). The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson.