Authors: Arianna Ciula

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: digital palaeograohy; intermedia studies; modelling

Digital Palaeography: What is digital about it?

Compared to the tradition of analytical palaeography it builds on, how is digital palaeography transformative? In this paper 1 I will reflect on the emergent meanings and possible research directions of digital palaeography by analysing the last twelve years of approaches and conceptualisations in the field. Moving between a formal and an historically situated analysis, I will show how digital approaches relate to the scholarly tradition of the study of handwriting and writing systems as a whole. Digital palaeography will emerge well positioned to represent the complexity of handwritten objects from an unfamiliar perspective by departing from the structure of the expression of handwriting (text as shape).

1. Words in context

The adoption and development of digital tools and resources for palaeography and manuscript studies are intertwined with fluctuating cultural attitudes (Busa, 1961; Morando, 1961; 2 McCarty, 2014b; Nyhan et al., 2015). The convergence towards the use of digital 3 coupled with humanities — digital humanities 4 — and therefore palaeography — digital palaeography — denotes the methodology of research being enabled rather than the symbolic form of its objects of analysis or of its outcomes. The scope within which I propose to discuss digital palaeography 5 is hence mainly methodological.

| Terms | Semantics | Overall emergent meaning |

| Computational (e.g. Computational Palaeography) | Process-ability of data | Digital Palaeography ⊃ Computational Palaeography |

| Digital (e.g. digital vs. analogue) | Representational form of data | |

| Digital + (e.g. Digital Humanities; Digital Palaeography) | Research methodology |

A formal knowledge of handwriting — e.g. about scripts morphology or terminology used to describe it — 6 Not only palaeography as a discipline — from the 1930s with Bischoff at least, onwards — has subscribed to analytical methods, but more in general the perception of text as divisible entity in opposition to the notion of the ungraspable composition of images has prevailed in humanistic enquiries with few exceptions (e.g. semiotics of art). 7 Computer sciences and image processing techniques offer an addendum, a perspective that suits nicely methodological traditions and inclinations of the classificatory minds of palaeographers. Yet, my aim in this paper is to identify any transformative aspects (table 1). So, even if digital palaeography follows a long tradition of analytical approaches to handwriting and an even longer human wish to control writing systems, does it actually affect our conceptualisation of handwriting? How is digital palaeography transformative (in the sense of digital +)? or is there a digital + palaeography?

2. Projects rationales and self-narratives

I will summarise some 2004-onwards projects and activities (Ciula, 2004a, 2004b, 2005a, 2005b, 2005c, 2009;DigiPal, 2011-14; Exploratory Workshops, 2011) 8 which witness a critical engagement with digital technology, informed by diverse modelling processes and a constructive discussion of the limitations of computational tools. These approaches challenge the notion of palaeography as an auxiliary discipline towards a renewed return to an “integral” (Boyle, 1984) perspective which places palaeography within a wider multi and interdisciplinary framework, linking it with philology, linguistics and even cognitive sciences. 9 The analysis on terminology as well as an overview of practices put the emphasis on a self-reflective approach around the analysis of handwriting beyond strictly computational concerns.

3. Creating and deflating models

In addition, I will reflect on the potentially productive dilemma digital palaeography approaches suffer from; a dilemma that is made more acute in recent practices compared to the already vivid debates in the 1970s between the historical and “Cartesian” approach (Gumbert, 1976) and in the 90s (Costamagna et al., 1995, 1996). On one hand, palaeographers engaged with the digital are busy building things, what Godfrey-Smith (2009: 108) would call a specific type of models or “imaginary concreta” (creatures in between reality and fiction, between the schematic and the concrete); on the other hand, they are engaged in reflecting about their own practice and in so doing deflate the same models they build. 10

In a paper questioning the connections between a scriptorium and its products, Ganz states: “searching for the distinctive details of letter forms shared by scribes may risk the application of an over rigid positivism to the study of manuscripts.” (Ganz, 2015)

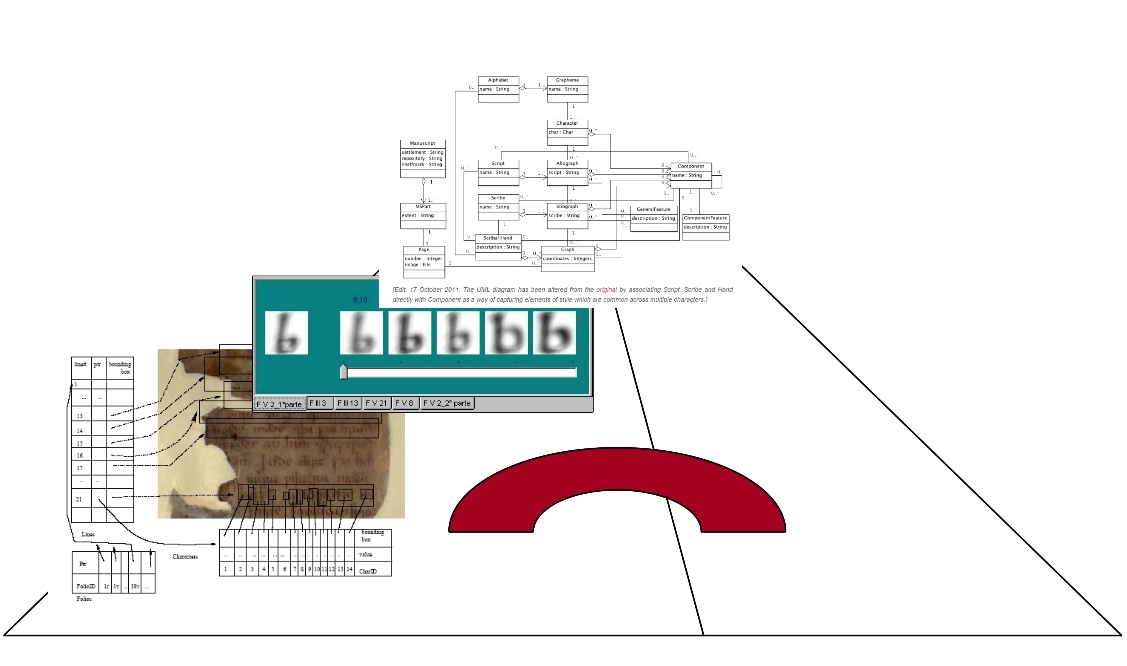

Not to dismiss this warning against positivism in digital humanities, 11 I will claim that what a digital palaeography approach as contextualised earlier on brings to the fore is precisely this awareness and hence the questioning of the 'mechanics' of a topographical or taxonomical analysis. By asking “what is the unit of handwriting? what we considered it to be?,” a digital palaeographer is aware that even by getting closer to the supposed materiality of the artefact — e.g. through high resolution images and microscopically segmented image features — she does not lose the lenses palaeographers have being using for interpreting such artefacts in the past, but can consciously decide to put them to test. In this lies one of the paradoxes of the digital and of modelling more in general: it brings perceptual materiality to our scrutiny while taking us away from it. The digital models are used to analyse the objects they are models of, but are also self-reflective tools to question those same models. 12

4. Semantics and materiality

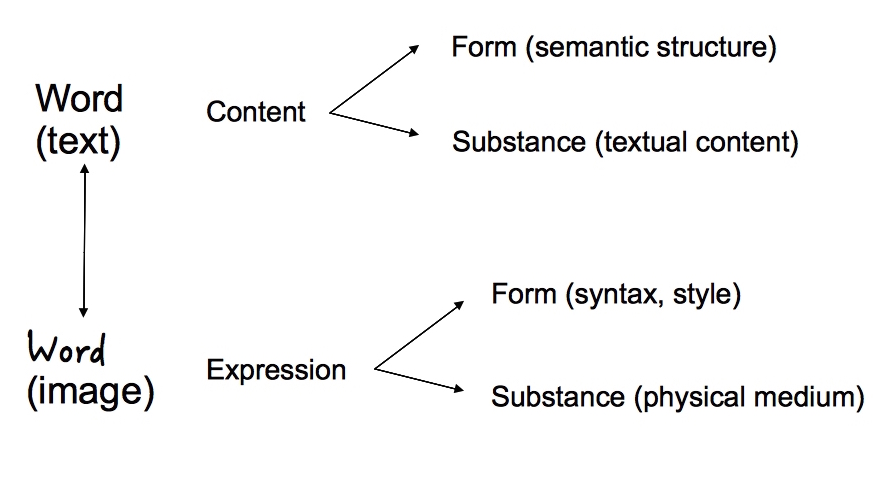

Palaeographic research with its focus on the perception of handwriting in morphological terms is a reminder that the handwriting manifests itself as an artefact that is rationalised and divided (hence constructed) only after it is given. By bringing to the fore the picture of writing or the writing as picture (cf. “text as shape” vs. “texts as meaning” in Hassner et al., 2012: 193), palaeographical studies live on the intermedia dimension of handwriting. By this I intend the crossing of the analytical media border between the sensorial and the conceptual qualities of handwriting, form and meaning, visible and invisible, between token and type, langue and parole. An adapted Hjelmslevian semiotic model of language exemplifies this intermedia dimension of writing. 13

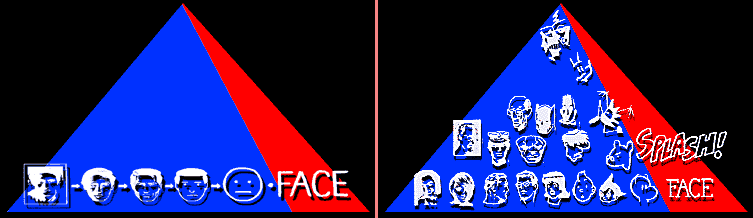

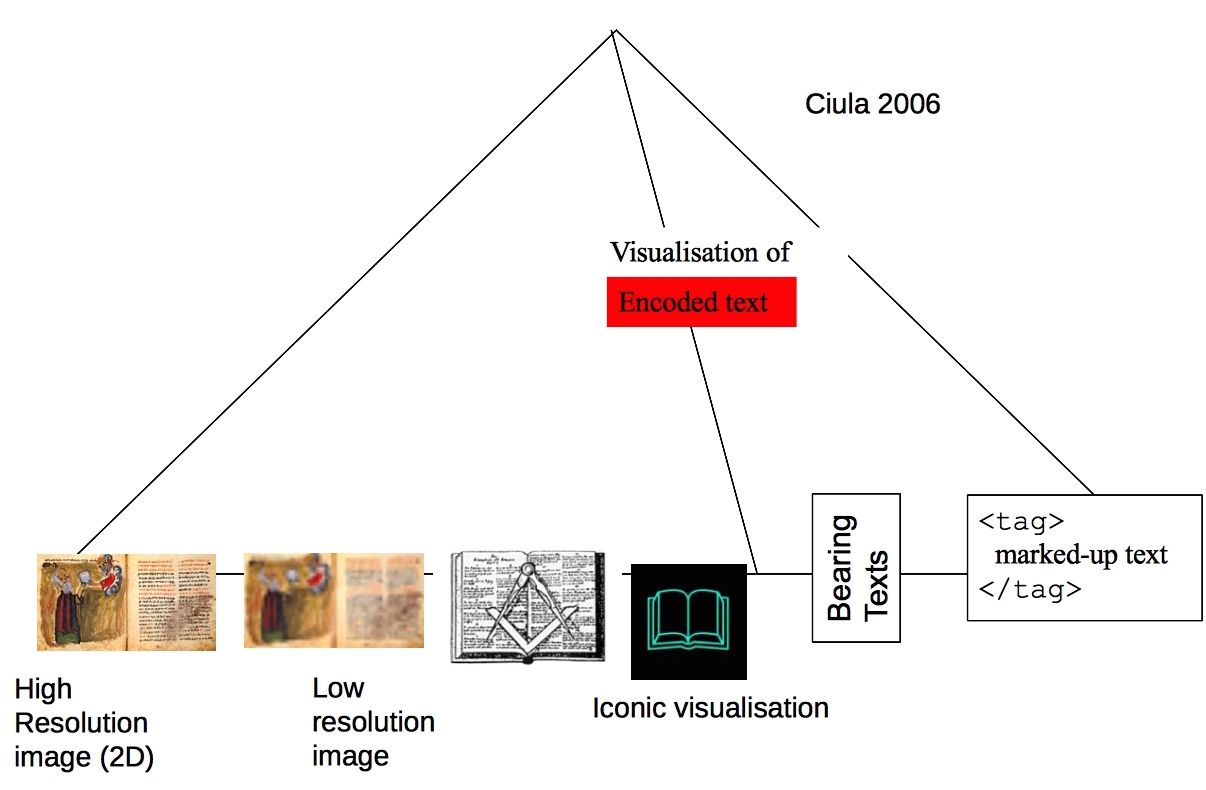

These reflections will allow me to sketch the intermedia borders where I think digital palaeography sits. I will build on an unpublished paper (Ciula, 2006) where I used McCloud's (1994) triangular map of visual iconography to represent the relationships between cultural textual objects and their digital (visual) representations both in graphical and in textual forms. 14

The visualisation of encoding is an example of structure-oriented visualisation which shows how a graphic rendering of the text does not have to relate unequivocally to features of the textual object as expression (whether form or substance of the expression) but can rather represent one or more supposed structures of the textual content. When made explicit and visible, the structure of the content on the textual-symbolic side can play a fundamental role in the implementation of a thoughtful connection between the image-iconic representation/s of the text and the textual-symbolic content representation/s of a cultural object. 15

Following this analysis, digital paleographic methods (inclusive of image processing, image annotation and conceptual models blending morphology and semantics) will be theorised as enhancers of iconic representations of textual artefacts. They can bridge the sensorial/perceptive and structural/conceptual interpretations of handwriting, material and mental knowledge of text, visual and textual, spatial and temporal.

In my 2006 paper, I concluded that for a digital resource to be inspired by and to promote research based on the material/perceptual aspects of a cultural object, a high quality graphical representation of the cultural object is essential but not sufficient. In specular terms to what Buzzetti (2006) 16 says about the symbolic components of textual objects, this paper will argue that the scope of digital palaeography lies in anchoring the structure of the expression of image-texts to the structure of their content, in other words in bridging the “semantic model” of a handwritten source to at least some of the material aspects of the artefact.

5. Conclusions

Digital palaeography builds on the tradition of analytical palaeography. How is it then transformative or is there a digital + palaeography? Some digital palaeography projects and initiatives, including my own doctoral research, claim to be transformative by advocating for “integral” palaeography and by distancing themselves from a purely computational approach. Some also adopt a self-reflective perspective on the modelling of handwriting in a digital environment, for instance, by testing ontological commitments, categories, classifications of handwriting; in so doing they deflate the models they build. Further, when contextualised within an analysis of the border between form and meaning of handwritten sources, digital palaeography approaches can can be used to connect the structure of expression of handwriting with structures of meaning. A digital model which embeds both structure of expression and structure of content of the handwriting is then theorised as a unique contribution to reconstruct material textuality of cultural artefacts by bridging visual and symbolic elements of texts, spatial and temporal, perception and interpretation. Ultimately, digital palaeography can be transformative by bridging the semantics of written artefacts with their materiality.

- Boyle, L. E. (1984). Medieval Latin Palaeography: A Bibliographical Introduction. University of Toronto Press.

- Busa, R. (1961). L’analisi linguistica nell’evoluzione mondiale dei mezzi d’informazione. Almanacco Letterario 1962. Milano: Bompiani, pp. 103–17.

- Buzzetti, D. (2006). Biblioteche digitali e oggetti digitali complessi: Esaustività e funzionalità nella conservazione. Archivi Informatici per Il Patrimonio Culturale, vol. 114. (Contributi Del Centro Linceo Interdisciplinare «Beniamino Segre»). Roma: Bardi Editore, pp. 41–75 http://web.dfc.unibo.it/buzzetti/dbuzzetti/pubblicazioni/lincei2003.pdf.

- Buzzetti, D. and Rehbein, M. (2008). Towards a model for dynamic text editions. In Opas-Hänninen, L. L., Jokelainen, M., Juuso, I. and Seppänen, T. (eds), Digital Humanities 2008. Oulu: University of Oulu, pp. 78–81 http://www.ekl.oulu.fi/dh2008/Digital%20Humanities%202008%20Book%20of%20Abstracts.pdf.

- Cecire, N. (2011). When Digital Humanities Was in Vogue. Journal of Digital Humanities, 1(1) http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-1/when-digital-humanities-was-in-vogue-by-natalia-cecire/.

- Ciula, A. (2004a). Digital palaeography. Digital Resources for the Humanities. Newcastle.

- Ciula, A. (2004b). Modelli di scrittura carolina. Gazette Du Livre Médiéval, 45: 27–38.

- Ciula, A. (2005a). Digital palaeography: using the digital representation of medieval script to support palaeographic analysis. Digital Medievalist, 1(Spring) http://www.digitalmedievalist.org/journal/1.1/ciula/.

- Ciula, A. (2005b). Paleografia e informatica. L’applicazione del software SPI al corpus di manoscritti senesi University of Siena Ph.D.

- Ciula, A. (2005c). Un progetto di ricerca. L’applicazione del software SPI ai codici senesi. In Pérez González, C. and Valcárcel Martínez, V. (eds), Estudios de poesia medieval. Vitoria: Findación Instituto Castellano y Leonés de la Lengua, pp. 305–22.

- Ciula, A. (2006). Cultural Objects in Digital Resources: Imagining the Text. CLiP 2006: Conference Abstracts: Literatures, Languages and Cultural Heritage in a Digital Worldly. London: Office for Humanities Communication http://legacy.cch.kcl.ac.uk/clip2006/redist/abstracts_pdfold/paper34.pdf (accessed 28 February 2016).

- Ciula, A. (2009). The Palaeographical Method under the Light of a Digital Approach. In Rehbein, M., Schaßan, T. and Sahle, P. (eds), Kodikologie Und Paläographie Im Digitalen Zeitalter - Codicology and Palaeography in the Digital Age. (Schriften Des Instituts Für Dokumentologie Und Editorik 2). Norderstedt: Books on Demand (BoD), pp. 219–35 http://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/2971/.

- Ciula, A. and Marras, C. (in press). Circling around texts and language: towards ‘pragmatic modelling’ in Digital Humanities. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 10(3).

- Costamagna, G., Gilissen, L., Gasparri, F. and Pratesi, A. (1995). Commentare Bischoff. Scrittura e civiltà, 19: 321–52.

- Costamagna, G., Gilissen, L., Gasparri, F. and Pratesi, A. (1996). Commentare Bischoff. Scrittura e civiltà, 20: 401–07.

- Dworkin, C., Morris, S. and Thurston, N. (2012). Information as material http://www.informationasmaterial.org/.

- Eyers, T. (2013). The perils of the ‘digital humanities’: New positivisms and the fate of literary theory. Postmodern Culture, 23(2).

- Faulhaber, C. (2015). 28.814 ‘digital humanities’: first occurrence? Humanist Discussion Group http://lists.digitalhumanities.org/pipermail/humanist/2015-March/012769.html (accessed 27 February 2016).

- Fischer, F., Fritze, C. and Vogeler, G. (eds). (2011). Kodikologie Und Paläographie Im Digitalen Zeitalter 2 - Codicology and Palaeography in the Digital Age 2. (Schriften Des Instituts Für Dokumentologie Und Editorik 3). Norderstedt: Books on Demand (BoD) http://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/4337/.

- Ganz, D. (2015). Can a Scriptorium Always be Identified by its Products?. In Nievergelt, A., Gamper, R., Bernasconi Reusser, M., Ebersperger, B. and Tremp, E. (eds), Scriptorium. Wesen - Funktion - Eigenheiten. (Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für die Herausgabe der mittelalterlichen Bibliothekskataloge Deutschlands und der Schweiz). München: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 51–62.

- Godfrey-Smith, P. (2009). Models and fictions in science. Philosophical Studies, 143(1): 101–16.

- Gumbert, J. P. (1976). A proposal for a Cartesian nomenclature. In Gumbert, J. P. and Haan, M. J. M. de (eds), Essays Presented to G. I. Lieftinck, vol. IV. (Miniatures, Scripts, Collections). Amsterdam: A. L. Van Gendt and Co.

- Hassner, T., Rehbein, M., Stokes, P. A. and Wolf, L. (2012). Computation and Palaeography: Potentials and Limits. Dagstuhl Perspectives Workshop 12382 (Dagstuhl Reports). Dagstuhl: Schloss Dagstuhl - Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik http://drops.dagstuhl.de/opus/volltexte/2013/3890/pdf/dagrep_v002_i009_p184_s12382.pdf (accessed 28 February 2016).

- Hassner, T., Rehbein, M., Stokes, P. A. and Wolf, L. (2013). Computation and Palaeography: Potentials and Limits. Dagstuhl Perspectives Workshop 12382 (Dagstuhl Manifestos). Dagstuhl: Schloss Dagstuhl - Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik http://drops.dagstuhl.de/opus/volltexte/2013/4167/ (accessed 28 February 2016).

- Hirtle, P. (2000). Editorial. D-Lib Magazine, 6(4) http://www.dlib.org/dlib/april00/04editorial.html.

- McCarty, W. (2014a). 27.745 digital knowledge Humanist Discussion Group http://lists.digitalhumanities.org/pipermail/humanist/2014-January/011672.html (accessed 28 February 2016).

- McCarty, W. (2014b). Getting there from here. Remembering the future of digital humanities Roberto Busa Award lecture 2013. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 29(3): 283–306.

- McCloud, S. (1994). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. First HarperPerennial edition. HarperCollins Publishers.

- Montecchi, G. (1998). Gli atlanti dei caratteri tipografici: considerazioni preliminari e propeduetiche dagli scritti di Sigismondo Fanti. In Leonardi, C., Morelli, M. and Santi, F. (eds), Modi di scrivere: tecnologie e pratiche della scrittura dal manoscritto al CD-ROM. Atti del convegno di studio della Fondazione Ezio Franceschini e della Fondazione IBM Italia. Certosa del Galluzzo, 11-12 ottobre 1996. (Quaderni di cultura mediolatina 15). Spoleto: Centro italiano di studi sull’Alto Medioevo, pp. 107–30.

- Morando, S. (ed). (1961). Le due culture - inchiesta. Almanacco Letterario 1962. Milano: Bompiani, pp. 143–44; 314–17.

- Nyhan, J., Flinn, A. and Welsh, A. (2015). Oral History and the Hidden Histories project: towards histories of computing in the humanities. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30(1): 71–85.

- Pierazzo, E. (2013). A conceptual model of Text, Documents and Work - Part 1 Elena Pierazzo’s Blog http://epierazzo.blogspot.co.uk/ (accessed 28 February 2016).

- Pierazzo, E. (2015). Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories, Models and Methods. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Piper, A. (2015). Novel devotions: Conversional reading, computational modeling, and the modern novel. New Literary History, 46(1): 63–98.

- Rehbein, M., Schaßan, T. and Sahle, P. (eds). (2009). Kodikologie Und Paläographie Im Digitalen Zeitalter - Codicology and Palaeography in the Digital Age. (Schriften Des Instituts Für Dokumentologie Und Editorik 2). Norderstedt: Books on Demand (BoD) http://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/2939/.

- Sahle, P. (5-9 July). What is text? A Pluralistic Approach. Digital Humanities 2006 Conference Abstracts. Université Paris-Sorbonne: CATI, pp. 188–90 http://www.allc-ach2006.colloques.paris-sorbonne.fr/DHs.pdf.

- Sahle, P. (2013). Digitale Editionsformen. Zum Umgang mit der Überlieferung unter den Bedingungen des Medienwandels. Teil 3: Textbegriffe und Recodierung. [Preprint-Fassung] Universität zu Köln Ph.D. http://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/5013/ (accessed 18 February 2016).

- Stokes, P. A. (forthcoming). Computing and Palaeography in Theory: Some Historical Context for the Future. In Brookes, S., Rehbein, M. and Stokes, P. A. (eds), Digital Palaeography. (Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities). Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Stutzmann, D. Écriture médiévale & numérique http://oriflamms.hypotheses.org/ (accessed 28 February 2016).

- DigiPal: Digital Resource and Database of Manuscripts, Palaeography and Diplomatic http://www.digipal.eu/ (accessed 27 February 2016a).

- Exploratory Workshops: European Science Foundation http://www.esf.org/coordinating-research/exploratory-workshops.html (accessed 27 February 2016b).

- Models of Authority: Scottish Charters and the Emergence of Government, 1100–1250 http://www.modelsofauthority.ac.uk/ (accessed 28 February 2016c).