Authors: Dirk van Hulle, Mike Kestemont

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: Stylometry, Stylochronometry, diachronic models, Samuel Beckett, oeuvre

Stylochronometry and the Periodization of Samuel Beckett’s Prose

1. Introduction

Probably best known as the author of En attendant Godot / Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett was not only a bilingual playwright, but also a poet, translator, essayist and novelist. Notably his prose fiction is the focus of this contribution, in which we use quantitative methods to delineate a periodization of Beckett’s œuvre. In art studies in general, there is a tradition of distinguishing an ‘early’ and ‘late’ period in an artist’s work, sometimes with a distinct ‘middle’ period in between. The late Beethoven sonatas are a good example, or the early Rembrandt’s ‘smooth’ style versus the rough paint surfaces of the late Rembrandt. Nevertheless, it is often difficult to determine exactly when an author’s work moves from, say, the ‘early’ to the ‘middle’ stage.

In Beckett studies, we find a similar pattern of periodization, ending with the ‘late style’ (Gontarski, 1997). Peter Boxall (2015: 34) problematizes the idea of periodizing Beckett’s œuvre, but admits that it is hard not to parcel it into a beginning, a middle and an end: an early period up to and including the novel Watt, written during WOII; a rich middle period up to and including The Unnamable; and the later, ‘halting’ prose after the latter text. Numerous critics have proposed alternative periodizations, resulting in almost as many different periodizations as the number of critics that devised them. We therefore investigated what a non-human ‘interpreter’ would come up with as a periodization by means of stylometry.

In this paper, we apply methods from stylometry to the problem of periodizing Samuel Beckett’s prose. A novelty is that we restrict it to function word frequencies, which are a common object of research in stylometry, but which have hardly been considered in Beckett studies. An exception is Banfield, who suggested a four-phase evolution in Beckett’s oeuvre, partially on the basis of linguistic arguments. Our approach is related to ‘stylochronometry’ (Stamou, 2008), in which a text’s writing style is studied as a function of its date of composition, in accordance with recent research into the stylistic development of individual authors, such as Henry James (Hoover, 2014), W. B. Yeats (Forsyth, 1999) or Jack London (Juola, 2007).

2. Preprocessing

Here, we analyze Beckett’s prose fiction, in both French and English. We removed all non-authorial paratexts and only considered lower-case, alphabetical character strings. In the software repository accompanying this contribution ( https://github.com/mikekestemont/beckett), we present a tabular overview of the materials we collected, including the publication dates of the editions we used, the text’s length, etc. (Note that this repository also holds high-resolution versions of our plots, which will be much more readable on screen.) In terms of chronology, we focus on the moment when Beckett started working on a text in either language (Van Hulle et al., 2015).

We defined a relevant list of function words by extracting an initial list of the 300 most frequent words (MFW) from each corpus. From this list, we have manually removed non-grammatical words, which might correlate too strongly with the topic of particular texts. We refrained from removing common auxiliary verbs or personal pronouns, because they are interestingly tied to a text’s narrative perspective, as will become clear below. After this procedure, we were left with 162 function words for the English corpus and 169 for the French, the frequencies of which were scaled using z-scores.

3. Preliminary Analyses

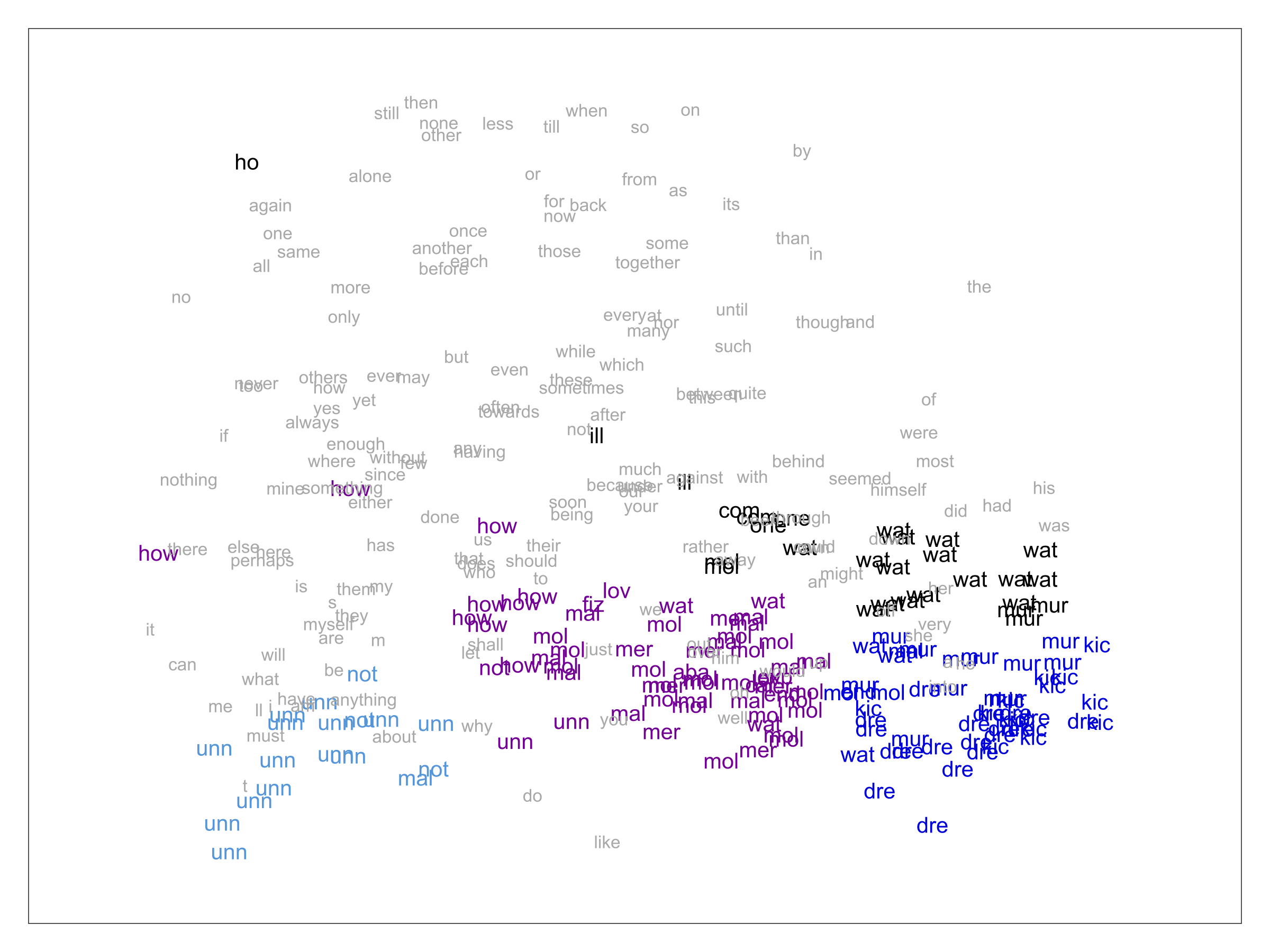

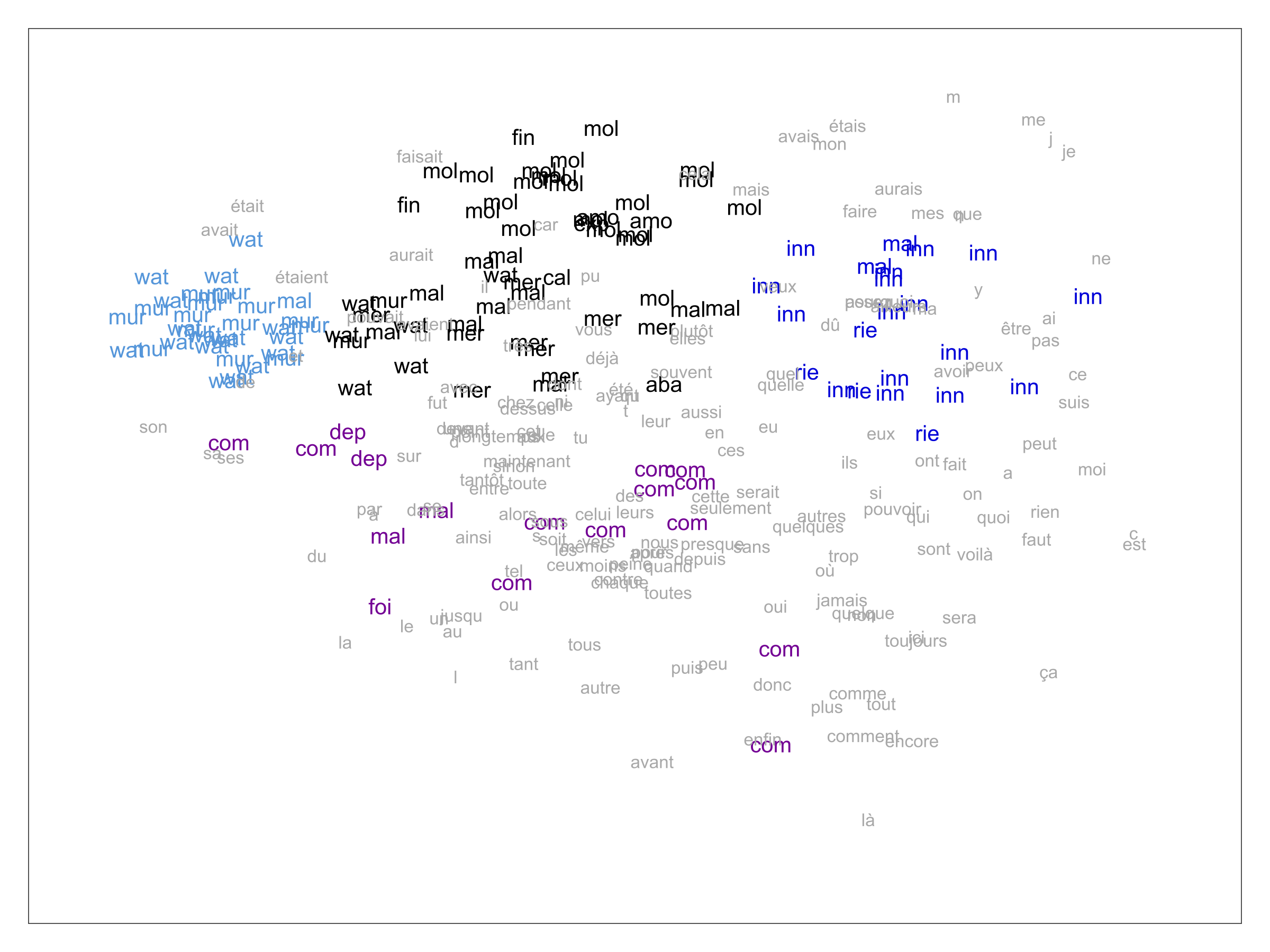

We carried out an exploratory analysis of the material, using principal components analysis (PCA, first two dimensions plotted in Figs. 1-2 for 3,761-word slices). This unsupervised procedure does not yet integrate any chronological information in the analyses, which will help establish whether Beckett’s œuvre might have a ‘natural’ chronological structure with respect to writing style. In Figs. 1-2, the horizontal spread is dominated by a threefold clustering, with some of Beckett’s earlier works clustering in the far left. The loadings reveal that these works are characterized by a high frequency of words related to a third-person narrative perspective ( he, she, his, has, etc.). To the far right, we find a tight sample cloud corresponding to some of Beckett’s post-war works, such as The Unnamable and Texts for Nothing. These texts can be characterized by the use of first-person pronouns ( I, me) in combination with impersonal pronouns such as it and there, which suggests that these texts focus on the relation between an ‘I’ and his non-personal surroundings.

Texts from the in-between period (such as Molloy and Watt) also hold the middle in the horizontal distribution of samples. In both languages, samples from later works jump out with respect to the vertical dimension – e.g. Worstward Ho in English, which is characterized by a rich mix of fairly abstract words, with an indeterminate semantics. Both scatterplots horizontally create an opposition between earlier and later writings in Beckett’s oeuvre, focusing on an opposition between a first-person and a third-person perspective. In the vertical dimension, both analyses reveal on a vocabulary shift, in Beckett’s late writings, towards a more abstract and indeterminate vocabulary.

4. Chronological Analyses

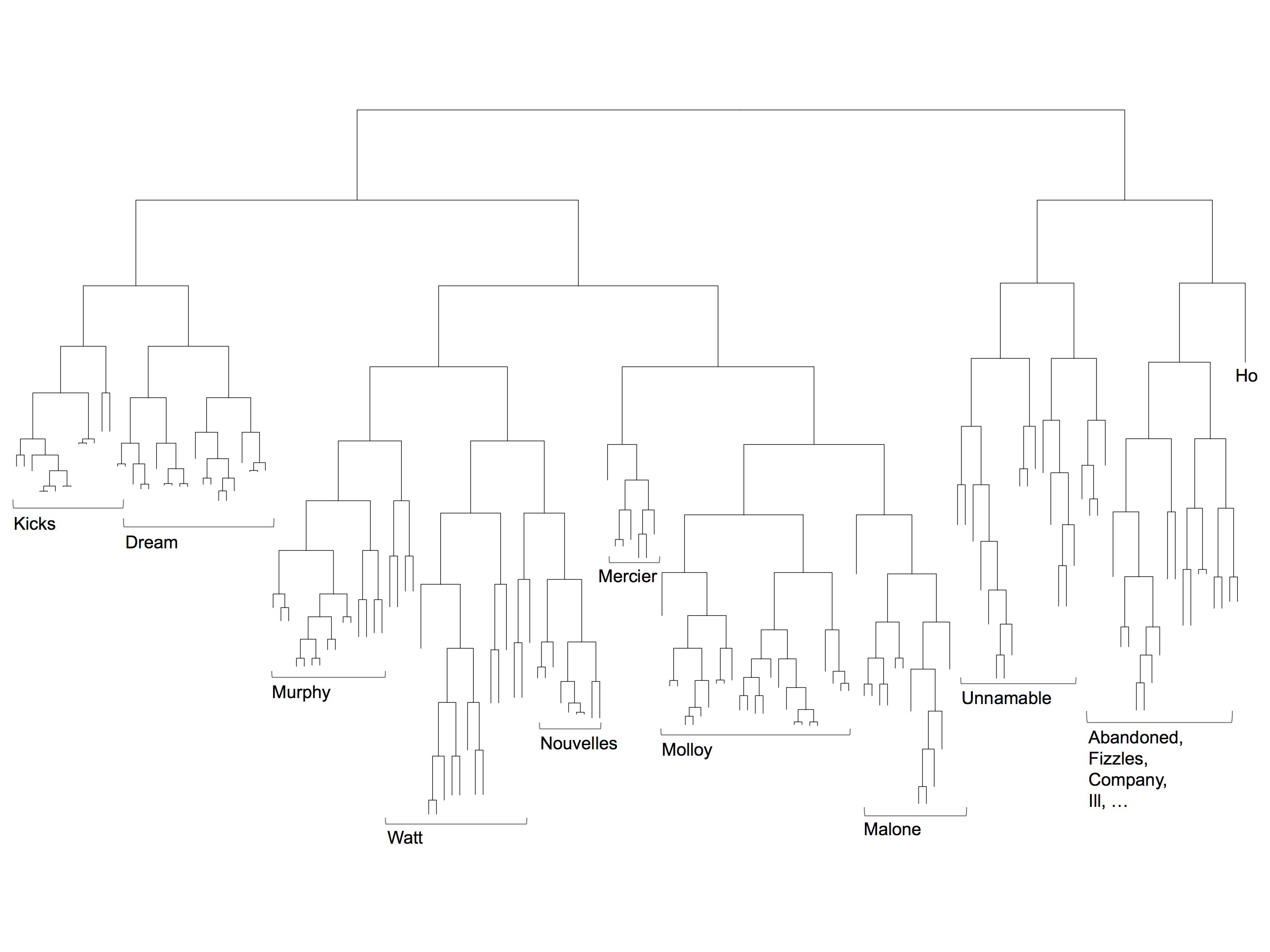

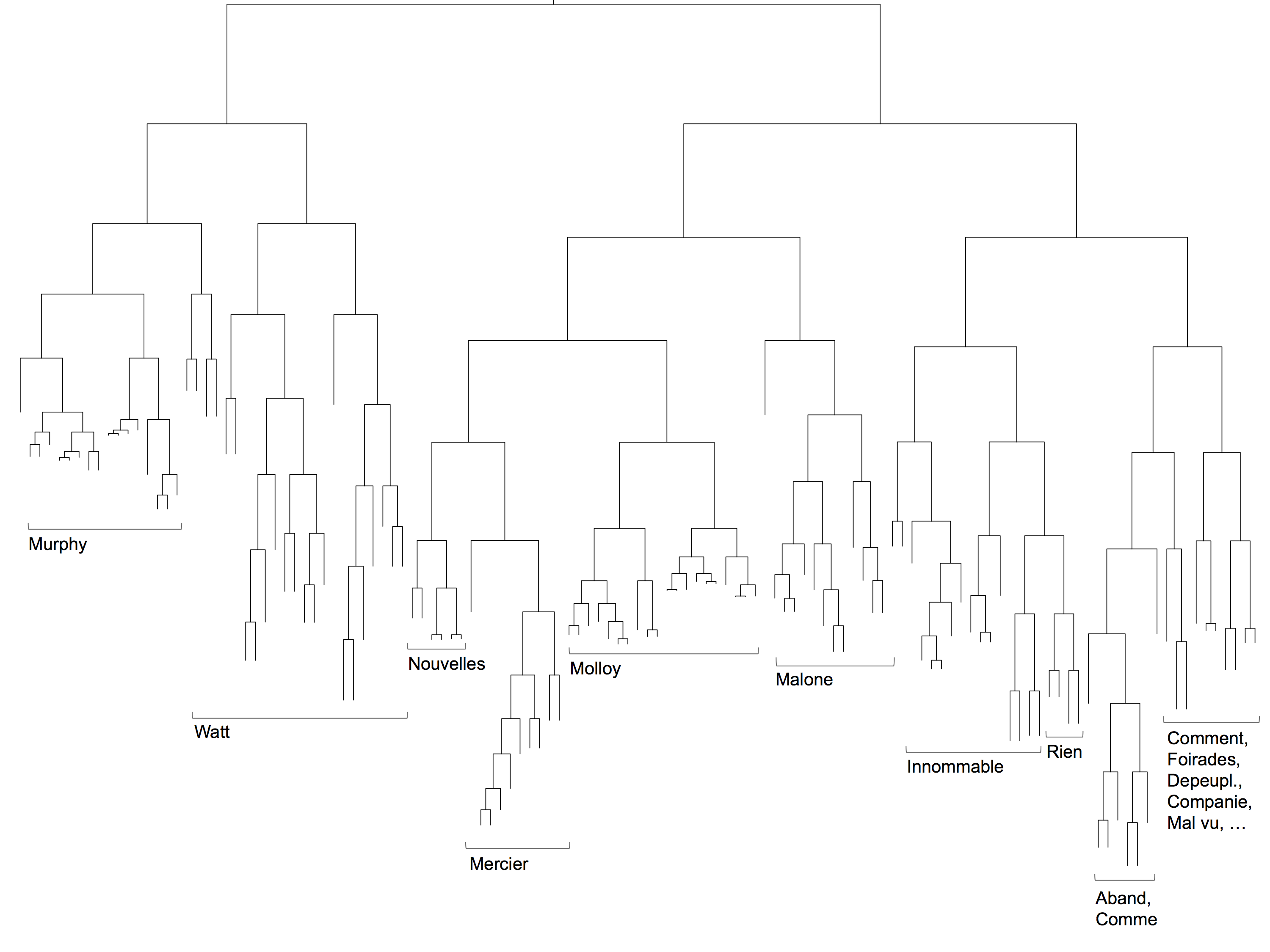

The previous analyses were ignorant of the diachronic structure of the data: samples from Beckett’s early works could just as easily cluster with later writings. This prevented us so far from identifying clear turning points in Beckett’s career. Variability-based Nearest Neighbour Clustering or VNC (Gries et al., 2012) is a method for the diachronic analysis of corpus linguistic data. VNC aims to identify distinct temporal stages, by pinpointing the main turning points. In traditional cluster analyses, each node can be freely combined with any other node in the tree, thus potentially scrambling the original chronological order of the data. VNC adds the constraint that only consecutive nodes, immediately adjacent in time, can form new clusters. This restriction enables analyses in which the chronological structure of the data is reflected in the top branches of trees, representing the main diachronic stages in the data.

We have run VNC on our data (Figures 3-4, Euclidean distances, Ward’s linkage), which resulted in clearer insight into the chronological structure of Beckett’s œuvre. The English prose, displays a clear initial cluster of Beckett’s earliest two novels, More Pricks than Kicks and Dream of Fair to Middling Women, which lack a French translation. Otherwise, the structures of Figs. 3-4 run remarkably parallel. Murphy and Watt constitute the second chronological cluster of works, together with the Nouvelles. Only at a higher level is the former group paired with the cluster consisting of Mercier and Camier, Molloy and Malone Dies. Interestingly, the original French versions of the Nouvelles are joined with the next cluster, whereas the English versions are joined with the previous cluster, which indicates a different status of this collection in both languages. The last major branch for both languages holds the tight clade representing The Unnamable, Texts for Nothing, How It Is and the series of shorter late works. In the English tree, Worstward Ho occupies a fairly pronounced position, emphasizing its special status.

The VNC analysis (supplemented by a more complex, bootstrapped analysis, which we do not describe in this abstract) generally supports the periodization of Beckett’s oeuvre into an early, middle and late ‘cluster’. In English these periods would cover, firstly, Beckett’s early works, More Pricks than Kicks and Dream of Fair to Middling Women; secondly the mid-career works, ranging from Murphy to Malone dies; and thirdly, a series of later works starting with The Unnamable. From the French prose, a similar periodization arises – although it clearly reflects the absence of any translated counterparts for More Pricks than Kicks and Dream of Fair to Middling Women.

Interestingly, our analyses invariably point to the beginning, rather than the end, of L’Innommable / The Unnamable as a major stylistic turning point, thus breaking up the unity of the so-called post-war ‘trilogy’. Additionally, From an Abandoned Work / D’un ouvrage abandonné – notwithstanding its short length – also often emerged as a major watershed. The question, however, is whether this result is to be interpreted as a turning point leading the way for Beckett’s later, experimental works, or as a sort of ‘re-turning point’, marking a temporary relapse into the idiom of the Nouvelles after L’Innommable. This might be a valuable pointer for further research, since this particular text does not seem to have played a significant role in the periodization debate so far. Additionally, it turns out to be more difficult in English than in French to model the transition from a young to a middle Beckett (also in the bootstrapped experiments). This result possibly reflects the fact that the original, English version of Watt was written relatively early (during the war), whereas its translation was made much later. In any case, this particular result offers grounds for a re-examination of the difference in evolution between Beckett’s French and English prose production, and in particular the role of Watt as a transitional novel.

- Banfield, A. (2003). Beckett’s Tattered Syntax, Representations,84: 6-29.

- Boxall, P. (2015). Still Stirrings: Beckett’s Prose from Texts for Nothing to Stirrings Still. In Van Hulle, D. (ed), The New Cambridge Companion to Samuel Beckett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 33-47.

- Gontarski, S. E. (1997). Staging Himself, or Beckett’s Late Style in the Theatre. Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd’hui, 6: 87-97.

- Forsyth, R. S. (1999). Stylochronometry with substrings, or: a poet yound and old. Literary and Linguistic Computing,14: 467-78.

- Gries, S. T. and Hilpert, M. (2012). Variability-based neighbor clustering: A bottom-up approach to periodization in historical linguistics. In Nevalainen, T. and Traugott, E. C. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the History of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 134-44.

- Hoover, D. L. (2014). A Conversation Among Himselves. Change and the Styles of Henry James. In Hoover, D. L., Culpeper, J. and O’Halloran, K. (eds), Digital Literary Studies: Corpus Approaches to Poetry, Prose, and Drama. New York: Routledge, pp. 90-119.

- Juola, P. (2007). Becoming Jack London. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 14: 145-47.

- Stamou, C. (2008). Stylochronometry: stylistic development, sequence of composition, and relative dating. Literary and Linguistic Computing,23: 181-99.

- Van Hulle, D. and Verhulst, P. (2015). Introduction: A Beckett Continuum and a Chronology of Beckett’s Writings. In Van Hulle, D. (ed), The New Cambridge Companion to Samuel Beckett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. XVII-XXXII.

- Van Hulle, D. and Kestemont, M. (2016). Periodizing Samuel Beckett's works: a Stylochronometric Approach. Style 50: forthcoming.