Authors: Peter Anthony Stokes, Stewart J. Brookes, Geoffroy Noël, John Reuben Davies, Tessa Webber, Dauvit Broun, Alice Taylor, Joanna Tucker

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: digital palaeography, digital diplomatics

The Models of Authority Project: Extending the DigiPal Framework for Script and Decoration

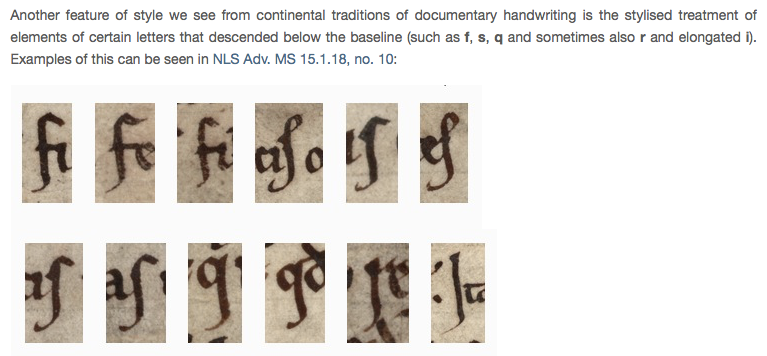

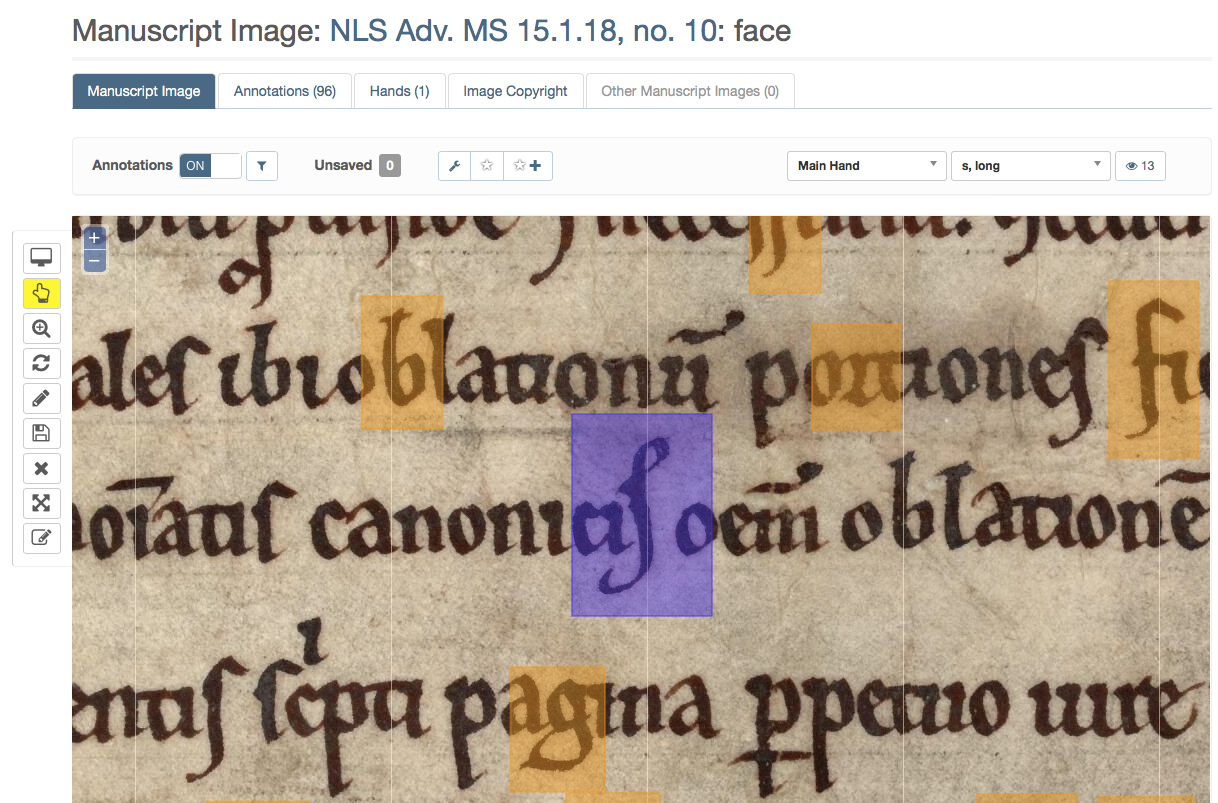

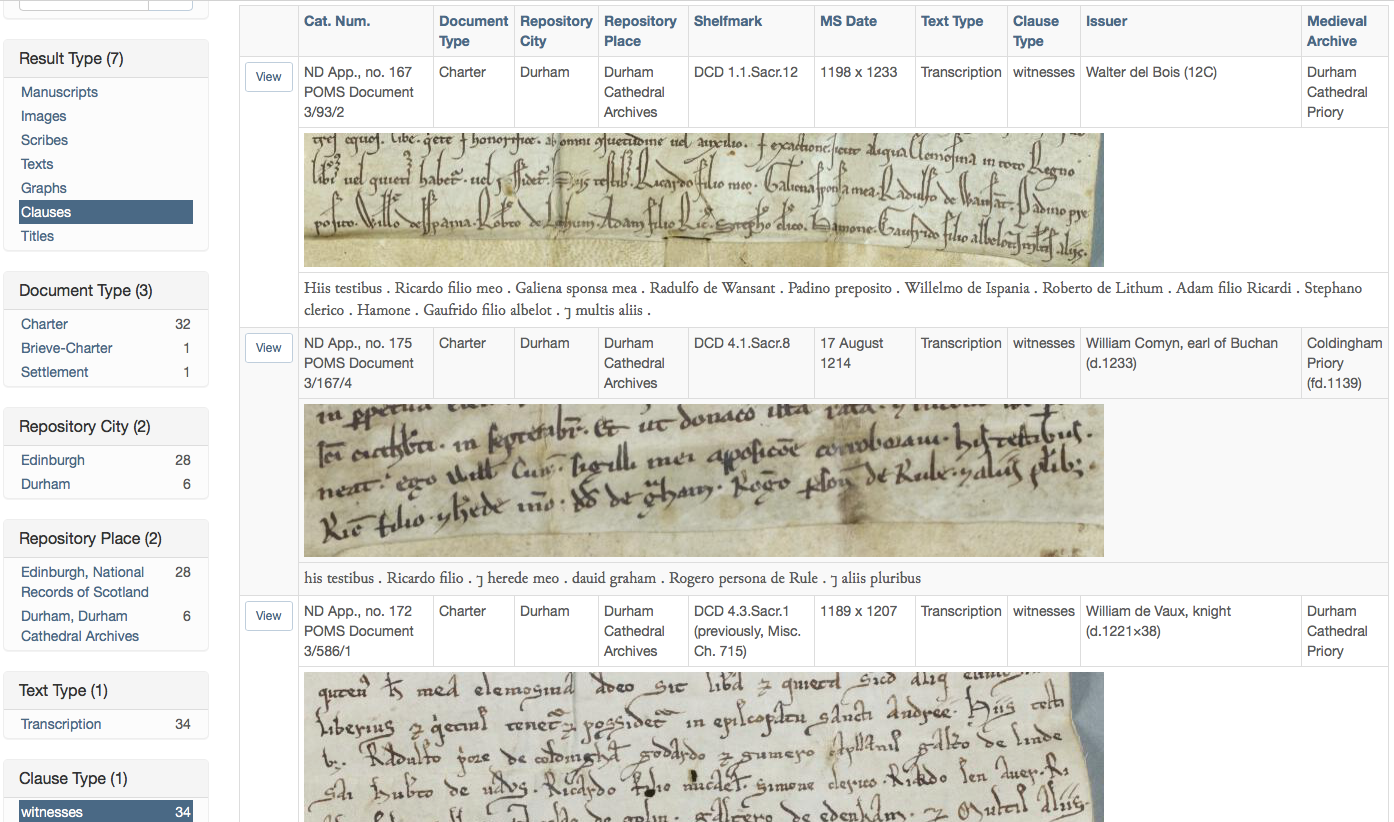

The DigiPal project for palaeography has featured in previous DH conferences (Stokes 2012; Stokes et al. 2014; Stokes 2015). It includes a generalised framework for the description and analysis of handwriting, initially applied to Old English of the eleventh century but subsequently extended to Latin, Hebrew, and decoration (Stokes et al. 2014); it incorporates a novel model for describing handwriting (Stokes 2012); and a recent addition allows the embedding of linked palaeographical images into prose description (Figures 1 and 2; see also Figure 3). The purpose of this poster is to present new developments which form part of two further major grants, one of which is the Models of Authority project (see also Exon 2015). Specifically, the focus here is on the incorporation of textual content into the model for handwriting.

Figure 1: Sample of Embedded Annotations in Palaeographical Description (Webber 2015). All images are linked by the framework to their full context in the manuscript page.

Figure 2: The Graph of s (fourth across in Fig. 1 above) in its page context.

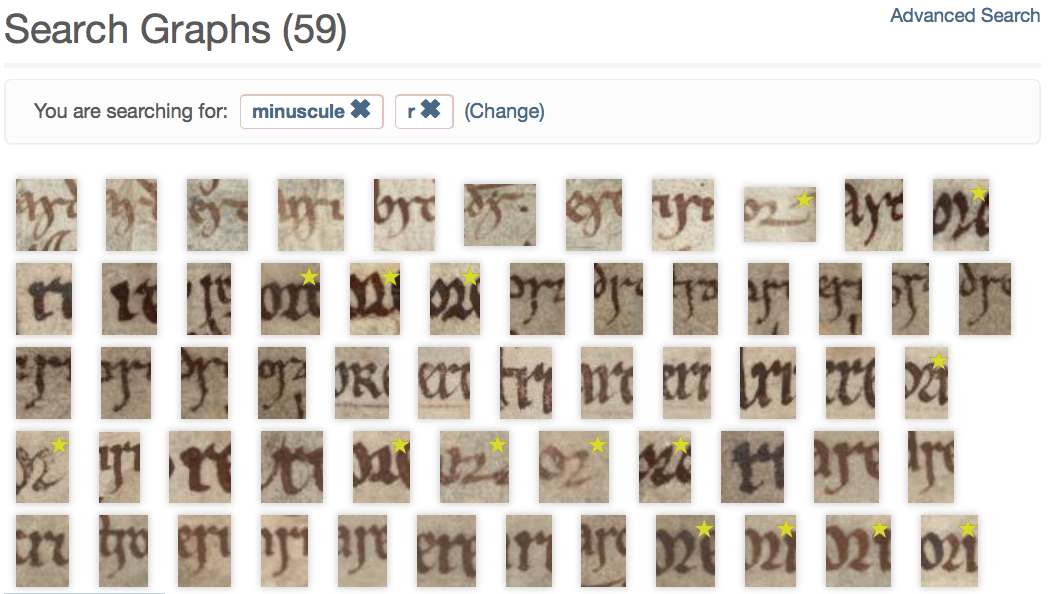

Figure 3: Sample forms (graphs) of r in the Models of Authority database. Examples of 2-shaped r are starred.

It is well known that features of handwriting depend not only on the type of manuscript and the social context of production, but also on the text itself, and the absence of this has always been a weakness of DigiPal (Stutzmann 2012; Stutzmann 2013). For Models of Authority, in contrast, a key premise is that the development of government in medieval Scotland is reflected in the choice of visual models behind the layout and handwriting of royal and local documents: this choice probably drew primarily on English counterparts, but elements from papal bulls, among others, are also visible (Broun 2015). It is helpful to note further that the text of these documents is relatively formulaic: this is common of charters in general, as noted in particular by the Charters Encoding Initiative (CEI) and utilised effectively by the Anglo-Saxon Charters project (ASChart), among others. However, connections between diplomatic formulae and script remain largely unexamined, at least in a digital context; certainly digital projects are underway that analyse the relationship between script and document (two examples are PUhMA and MoM-CA), but freely-available online frameworks are still lacking that allow queries like ‘show me images of d that appear in witness-lists of episcopal charters, and let me compare them with those of dispositive clauses’. Hence a key question of Models of Authority is whether matching the palaeography to the diplomatic formulae in this way might reveal new information about how the documents were put together, what models may lie behind them, and therefore how the nascent Scottish government may have seen itself particularly in relation to the English and Papal chanceries.

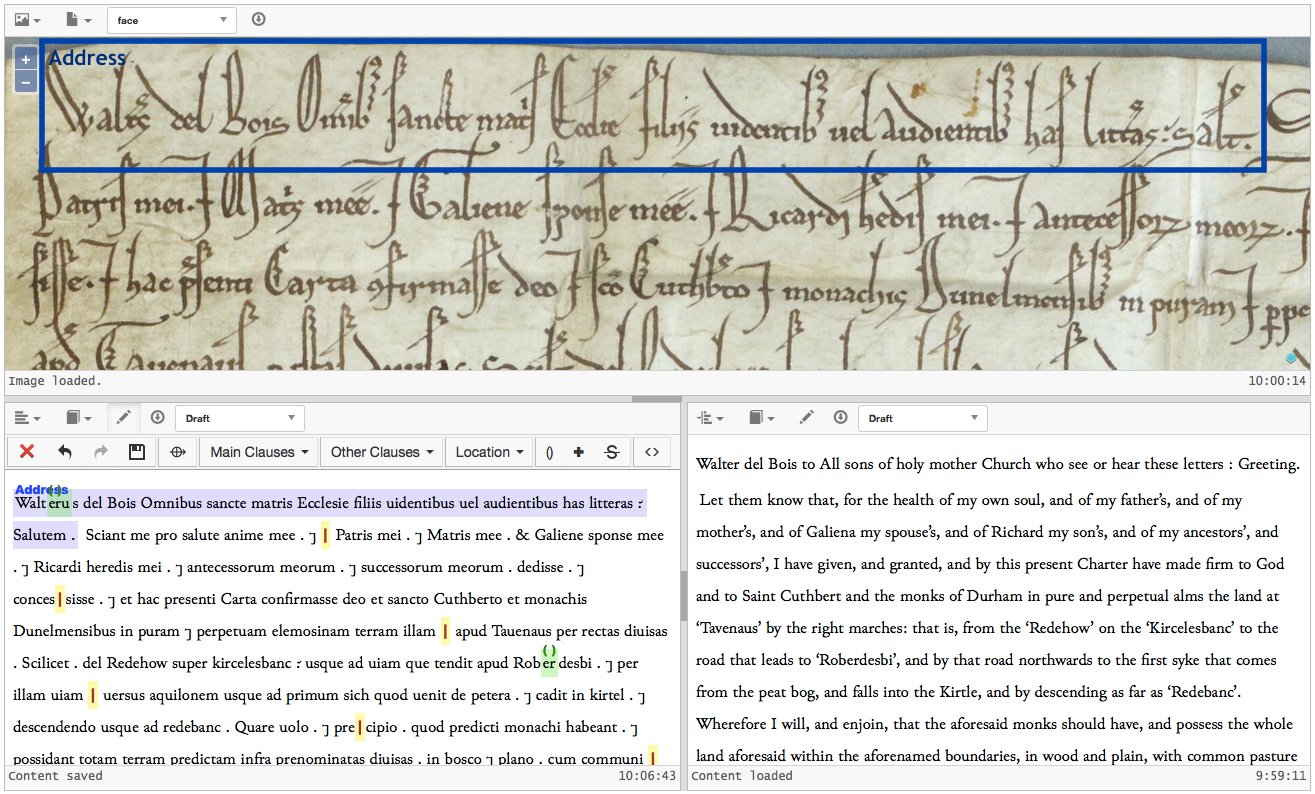

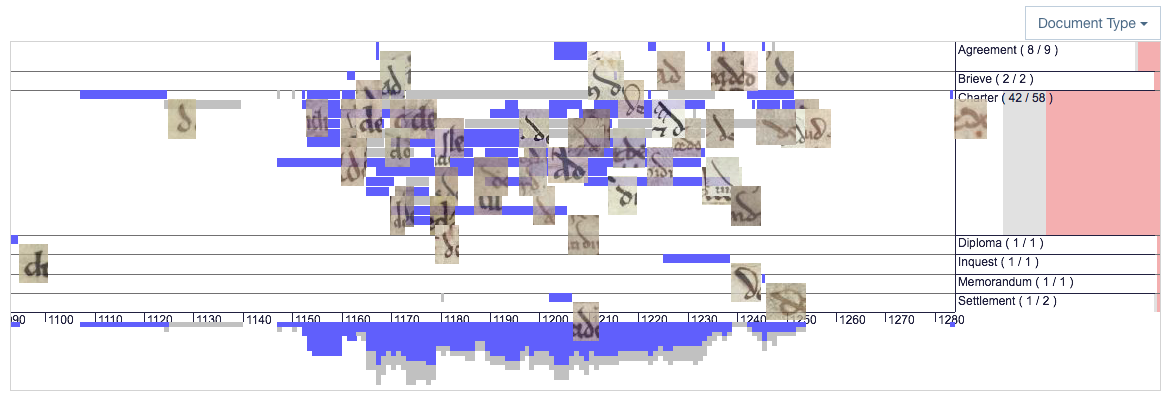

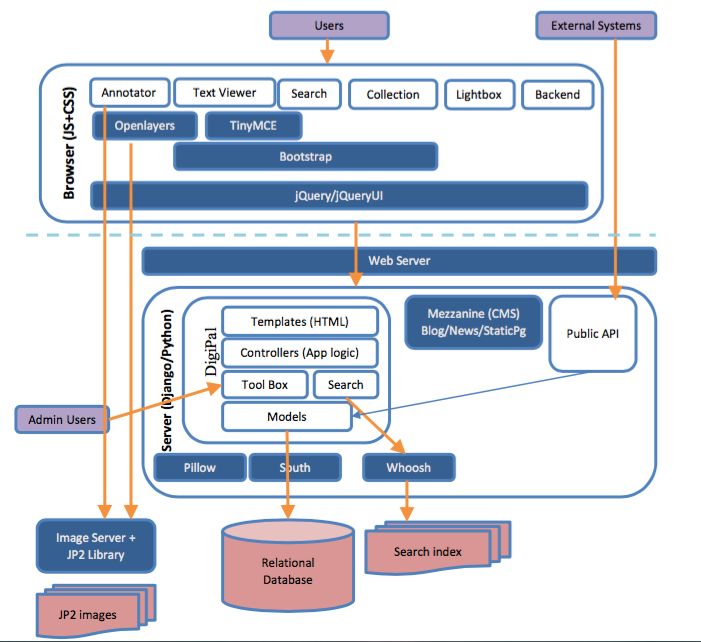

The DigiPal framework has therefore been extended by adding a generalised textual component, such that arbitrary marked-up texts (transcription, translation, codicological description, and so on) may be associated with palaeographical annotations and images and displayed in parallel with them (Figures 4–6). This allows the exploration of correlations between palaeographical forms and the corresponding text, comparing in this case the different clauses in the documents not just in terms of the text (as done in ASChart and others) but also as images of the corresponding clause in different documents. The integration of this into the DigiPal model for handwriting (described by Stokes 2012) therefore allows detailed palaeographical querying, such as filtering for images of all the letters with ascenders that appear in the address clause of the charter, or looking for variation in letter-forms in the witness lists. The former is of considerable interest because chancery scribes often add decorative elements to ascenders of letters, particularly in the first line of the text (visible in Figure 4), a practice which derives from Papal and ultimately Merovingian diplomatic practice; for the latter query, names of witnesses are normally written by the main scribe at the same time as the rest of the text but in some cases may also have been added later (Broun 2011, 258–65 and 280–7), so identifying differences in writing here can also be very significant. Beyond charters, the digital model generalises to other forms of linking from structured text to structured annotation, for instance at the glyph-by-glyph level advocated by Stutzmann (2013), and is also being applied elsewhere (Exon 2015).

Figure 4: Diplomatic Markup of Text and Image

Figure 5: Example query showing text and image of witness lists in private charters.

Figure 6: Prototype overview/timeline indicating shapes of d in documents of different type.

This addition of text introduces considerable complexity to the system, since it seeks to connect very different views of the original document: as transcription, translation, image and annotation; as scribal product (a set of interconnected and interacting letters) and diplomatic product (a set of textual formulae); an overview of the current architecture is shown in Figure 7. This integration of different views goes to the heart of an ongoing challenge in Digital Humanities, as perhaps best represented by the competing ‘textual’ and ‘documentary’ views in the TEI (2015; Pierazzo and Stokes 2011; see also Stokes and Noël 2010).

Figure 7: Overview of the current architecture

The proposed poster will therefore present the existing framework and integrated model, addressing the complexities described above. Live demonstrations will be available of Models of Authority, and of other instances of the framework such as DigiPal, Exon, and some that are not yet publicly available.

1. Acknowledgements

The Models of Authority project is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) under Grant Reference n° AH/L008041/1.

- ASChart. Anglo-Saxon Charters. London: King’s College. Available at http://aschart.kcl.ac.uk/. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Broun, D. (2015). Introducing the ‘Models of Authority’ project: Scottish charters c. 1100–c.1250. Models of Authority: Scottish Charters and the Emergence of Government. London: King’s College. Available at http://www.modelsofauthority.ac.uk/blog/intro/. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Broun, D. (2011). The presence of witnesses and the writing of charters. In Broun, D. (ed.), The Reality behind Charter Diplomatic in Anglo-Norman Britain. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, pp. 235–90. Available at http://paradox.poms.ac.uk/redist/pdf/chapter4.pdf. [Accessed 3 March 2016].

- CEI. Charters Encoding Initiative. Munich: Ludwig-Maximilians Universität. Available at http://www.cei.uni-muenchen.de/. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- DigiPal. (2010–14). Digital Resource and Database of Palaeography, Manuscript Studies and Diplomatic. London: King's College. Available at http://www.digipal.eu. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Exon. (2015–). The Conqueror’s Commissioners: Unlocking the Domesday Survey of SW England. London: King’s College. Available at http://www.exondomesday.ac.uk. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- PUhMA. Papsturkunden des hohen Mittelalters. Erlangen: University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. https://www5.cs.fau.de/de/papsturkunden-des-hohen-mittelalters/startseite/. [Accessed 3 March 2016].

- MoA (2015–). Models of Authority: Scottish Charters, c.1100–c.1250. London: King’s College. Available at http://www.modelsofauthority.ac.uk. [Accessed 3 March 2016].

- MoM-CA. Source Code of the Monasterium Collaborative Archive. https://github.com/icaruseu/mom-ca. [Accessed 3 March 2016].

- Pierazzo, E. and Stokes, P.A. (2011). Putting the text back into context: A codicological approach to manuscript transcription. In Fischer, F., Fritze, C. and Vogeler, G. (eds), Kodikologie und Paläographie im Digitalen Zeitalter 2 - Codicology and Palaeography in the Digital Age 2. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, pp. 397–430. Available at http://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/4360/. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Stokes, P. A., and Noël, G. (2010). Modelling and system design. Anglo-Saxon Cluster Project Report. London: King’s College. Available at http://www.ascluster.org/techinfo/analysis/system_design.html. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Stokes, P.A. (2012). Modeling medieval handwriting: A new approach to digital palaeography. In Meister, J.C. et al. (eds), DH2012 Book of Abstracts. Hamburg: University of Hamburg, pp. 382–5. Available at http://www.dh2012.uni-hamburg.de/conference/programme/abstracts/modeling-medieval-handwriting-a-new-approach-to-digital-palaeography. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Stokes, P.A., Brookes, S., Noël, G., Buomprisco, G., Marques de Matos, D., and Watson, M. (2014) The DigiPal framework for script and image. In Digital Humanities 2014 Book of Abstracts. Lausanne: 512–14. Available at http://dharchive.org/paper/DH2014/Poster-193.xml. Poster available at http://www.digipal.eu/media/uploads/uploads/images/blog_posts/2014/DH2014%20Poster.pdf. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Stokes, P. A. (2015). The problem of digital dating: A model for uncertainty in medieval documents. In Digital Humanities 2015 Book of Abstracts. Sydney: University of Western Sydney. Available at http://dh2015.org/abstracts/. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Stutzmann, D. (2012). Modélisation des signes graphiques (1). Écriture médiévale et numérique. Available at http://oriflamms.hypotheses.org/921. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Stutzmann, D. (2013). Ontologie des formes et encodage des textes manuscrits médiévaux: Le projet ORIFLAMMS. Document númerique 16(3): 81–95.

- TEI: Text Encoding Initiative (2015). Representation of primary sources. P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Version 2.9.1 revision 46ac023. Available at http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/PH.html. [Accessed 1 November 2015].

- Webber, T. (2015). The handwriting of Scottish charters 1100–1250 in the National Library of Scotland. Models of Authority: Scottish Charters and the Emergence of Government 1100–1250. King’s College London. http://www.modelsofauthority.ac.uk/blog/handwriting/. [Accessed 3 March 2016].