Authors: Mike Kestemont, Justin Stover, Moshe Koppel, Folgert Karsdorp, Walter Daelemans

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: stylometry, authorship verification, classical antiquity, julius caesar

Authorship Verification with the Ruzicka Metric

1. Introduction

Authorship studies have long played a central role in stylometry, the popular subfield of DH in which the writing style of a text is studied as a function of its author’s identity. While authorship studies come in many flavors, a remarkable aspect is that the field continues to be dominated by so-called ‘lazy’ approaches, where the authorship of an anonymous document is determined by extrapolating the authorship of a document’s nearest neighbor. For this, researchers use metrics to calculate the distances between vector representations of documents in a higher-dimensional space, such as the well-known Manhattan city block distance. In this paper, we apply the minmax metric – originally proposed in the field of geobotanics – to the problem of authorship attribution and verification. Comparative evaluations across a variety of benchmark corpora show that this metric yields better, as well as more consistent results than previously used metrics. While intuitively simply, this metric generally displays a regularising effect across different hyperparametrizations, and allows the more effective use of larger vocabularies and sparser document vectors. In particular the metric seems much less sensitive than its main competitors to (the dimensionality of) the vector space model under which the metric is applied.

Most authorship studies in computer science are restricted to present-day document collections. In this paper, we illustrate the broader applicability of the minmax metric by applying it to a high-profile case study from Classical Antiquity. The ‘War Commentaries’ by Julius Caesar ( Corpus Caesarianum) refers to a group of Latin prose commentaries, describing the military campaigns of the world-renowned Roman statesman Julius Caesar (100-44 BC). While Caesar must have authored a significant portion of these commentaries himself, the exact delineation of his contribution to this important corpus remains a controversial matter. Most notably, Aulus Hirtius – one of Caesar’s most trusted generals – is sometimes believed to have contributed significantly to the corpus. Thus, the authenticity and authorship of the Caesarian corpus is a philological puzzle that has persisted for nineteen centuries. In our paper, we shed new light on this matter.

2. Benchmarking

To properly evaluate the performance of the novel Ruzicka minmax metric, we turn to a publicly available benchmark corpora: the multilingual datasets (Dutch, English, Greek, and Spanish) used by the 2014 track on authorship verification in the PAN competition on uncovering plagiarism, authorship, and social software misuse. This track focused on the “open” task of authorship verification (as opposed to the closed set-up of authorship verification). Each dataset holds a number of “problems”, where given (a) at least one training text by a particular target author, (b) a set of similar mini-oeuvres by other authors, and (c) a new anonymous text, the task is to determine whether or not the anonymous text was written by the target author. A system must output for each of the problems a real-valued confidence score between 0.0 (“definitely not the same author”) and 1.0 (“definitely the same author”). By outputting the value of 0.5, a system can specify that it was not able to solve a problem. For each dataset, a fully independent training and test corpus are available (i.e. the problems, nor authors and texts in both sets do not overlap). Systems are eventually evaluated using two scoring metrics which were also used at the PAN: the established AUC-score, as well as the so-called c@1, a variation of the traditional accuracy-score, which gives more credit to systems that decide to leave some difficult verification problems unanswered. In the full paper, we offer a complete evaluation of all datasets: for the sake of brevity, this paper is restricted to a representative selection of results.

As common in text classification research, we vectorize the datasets into a tabular model, under a ‘bag-of-words’ assumption, which is largely ignorant of the original word order in document. Unless reported otherwise, we use character tetragrams below (Koppel et al., 2014), which yield generally acceptable results across corpora. We experiment with a number of different vector space models, the results of which can be summarized as follows:

- plain tf (where simple relative frequencies are used);

- tf-std, where the tf-model is scaled using a feature’s standard deviation in the corpus (cf. Burrows’s Delta: Burrows, 2002);

- tf-idf, where the tf-model is scaled using a feature’s inverse document-frequency (to increase the weight of rare terms).

- …

In our experiments, we focus on the Ruzicka ‘minmax’ distance metric, a still fairly novel algorithm in the field of stylometry. Just as the Euclidean or Manhattan distance, this metric will calculate a real-valued distance score between two document vector A and B as follows:

While the formula below uses the tf-model, the Ruzicka distance can of course be easily applied to other vector space models too. In our paper, we will offer a intuitive assessment of the desirable properties of this metric (e.g. in comparison to Burrows’s Delta).

3. General Imposters Framework (GI)

In our experiments, we make amongst others use of the General Imposters Method, a bootstrapped approach to authorship verification which has recently yielded excellent results. Fitting the verifier on the train data involves two steps. First, we calculate a distance score for the anonymous document in each problem, using Algorithm 1, in order to determine whether the anonymous text was written by the target author specified in the problem:

Thus, during k iterations (default 100), we randomly select a sample (e.g. 50%) of all the available features in the data set. Likewise, we randomly select m ‘imposter’ documents (default 30), which were not written by the target author. Next, we use a dist() function to assess whether the anonymous text is closer to any text by the target author than to any text written by the imposters. Here, dist() represents a regular, geometric distance metric, such as the Manhattan or Ruzicka metric. The score returned by Algorithm 1 has been characterized as a ‘second-order’ metric, because it does not rely on the rather comparison of document vectors. The general intuition here, is that we do not just calculate how different two documents are; rather we test whether the stylistic differences between them are consistent (a) across many different feature sets, and (b) in comparison to other randomly, sampled documents.

In the second stage, we attempt to optimize the distance scores returned by Algorithm 1, in the light of the specific evaluation measures used. We apply a score shifter (Algorithm 2), which attempts to define a ‘grey zone’ where the results seem too unreliable to output a score (cf. c@1):

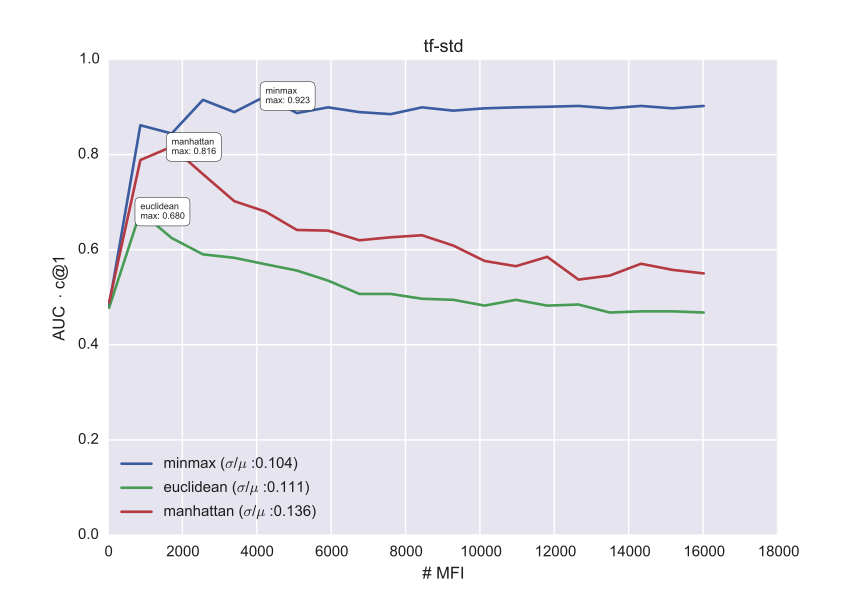

Through a grid search of different values between 0 and 1 for p1 and p2, we determine the settings which yield the optimal AUC x c@1 on the train data. In Fig. 1, we plot the optimal results which could be obtained on the train problems in the data set of Dutch Essays, for a specific combination of a metric and a vector space model. We ran the experiment 20 times, with increasing vocabulary truncations (e.g. the 1000 most frequent tetragrams). The results demonstrate how the Ruzicka minmax metric returns the most stable results across the experiments and clearly has a regularizing effect across different hyperparametrizations. In the full paper, we will present a complete evaluation of this system on all the PAN datasets, which in most cases yields surprisingly competitive scores on the test data, even without much corpus-specific parameter tuning. In the table below, we show the test results for Dutch essays corpus in terms of the AUC x c@1. The best combination reaches a AUC x c@1 of 0.886 on the test data (combination of minmax and std), whereas the best individual system submitted to PAN 2014 only reached 0.823 on that test dataset. Using randomized significance tests, we will additionally demonstrate the regularizing effect of the Ruzicka distance across vector spaces; its strong performance is also evident from Table 1.

|

Table 1: Final test results (AUC x C@1)

4. Corpus Caesarianum

To further illustrate the applicability of the Ruzicka metric for authorship problems in traditional philology, we also report a stylometric case study concerning the Corpus Caesarianum. This Corpus is a group of five commentaries Caesar’s military campaigns:

- Bellum Gallicum, the conquest of Gaul, 58 to 50 BC;

- Bellum civile, the civil war with Pompey, 49 to 48 BC;

- Bellum Alexandrinum, the campaigns in Egypt etc., 48 to 47 BC;

- Bellum Africum, the war in North Africa, 47 to 46 BC

- Bellum Hispaniense, a rebellion in Spain, 46 to 45 BC.

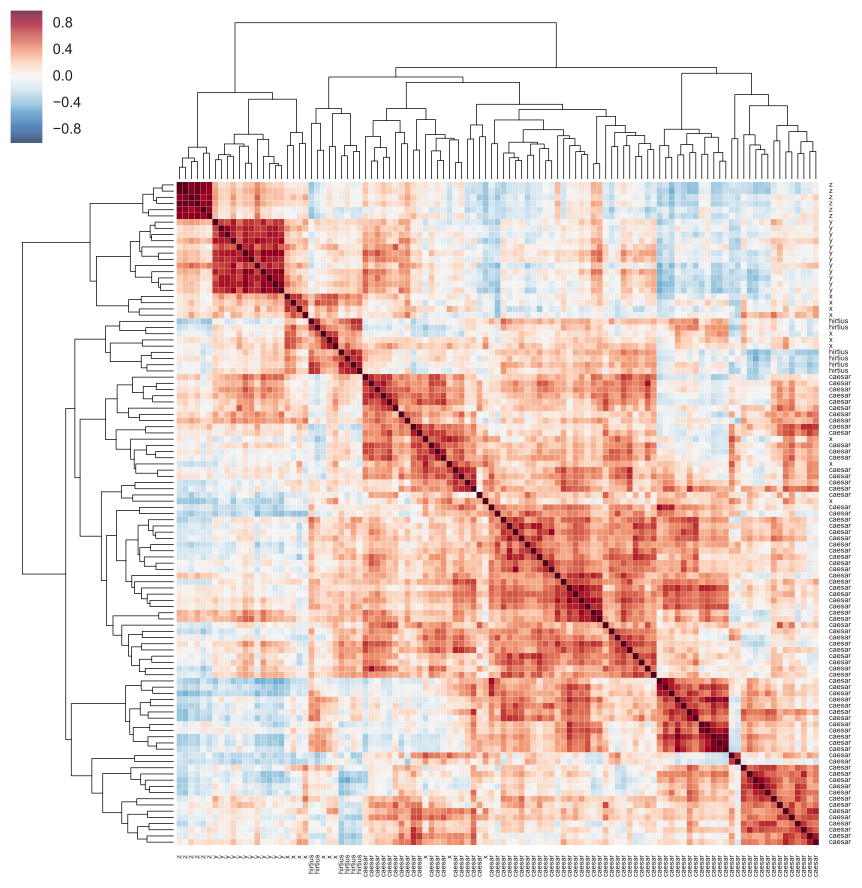

The first two commentaries are mainly by Caesar himself, the only exception being the final part of the Gallic War (Book 8), which is by Caesar’s general Aulus Hirtius. Suetonius, writing a century and a half later, suggests that either Hirtius or another general, named Oppius, authored the remaining works. We will report experiments which broadly supports the Hirtius’s own claim that he himself compiled and edited the corpus of the non-Caesarian commentaries. Figure 2, for instance, shows a heatmap-like visualisation, in which Hirtius’s Book 8 of the Gallic War clearly clusters with the bulk of the Alexandrian War (labeled x).

- Argamon, S. (2008). Interpreting Burrows’s Delta: Geometric and probabilistic foundations. Literary and Linguistic Computing,23: 131-47.

- Burrows. J. F. (2002). ‘Delta’: A measure of stylistic difference and a guide to likely authorship. Literary and Linguistic Computing,17: 267-87.

- Gaertner, J. and Hausburg, B. (2013). Caesar and the Bellum Alexandrinum: An Analysis of Style, Narrative Technique, and the Reception of Greek Historiography. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen.

- Koppel, M. and Winter, Y. (2014). Determining if two documents are written by the same author. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65: 178–87.

- Mayer, M. (2011). Caesar and the corpus caesarianum. In Marasco, G. (ed), Political auto-biographies and memoirs in antiquity: A Brill companion. Brill, Leiden, pp. 189-232.

- Stamatatos, E. et al. (2014). Overview of the author identification task at PAN 2014. In Working Notes for CLEF 2014 Conference, pp. 877-97.

- Stover, J., Winter, Y., Koppel, M. and Kestemont, M. (2016). Computational authorship verification method attributes a new work to a major 2nd century African author. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology,66: 239-42.