Authors: Kiyonori Nagasaki, Toru Tomabechi, Charles Muller, Masahiro Shimoda

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: word segmentation

Digital Humanities in Cultural Areas Using Texts That Lack Word Spacing

1.

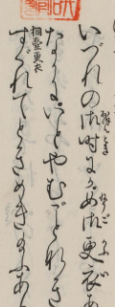

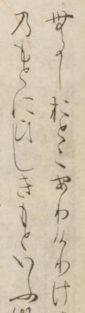

As most of modern and pre-modern western writing systems explicitly represent division of the words in a sentence by spaces or breaks, it has been easy to use computers to analyze texts based on each word and its meanings. However, there are several modern and pre-modern writing systems that do not explicitly indicate word separation in texts; that is, all words in a sentence are contiguous. A major contemporary representative of this kind of writing is seen in the language system of East Asia. Moreover, a popular Japanese pre-modern writing system called kuzushi-ji (cursive style characters) had often been presented with undivided characters even in typesetting until the late nineteenth century (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). As the lack of word-separation has been evoking not only ambiguity but also multiple interpretations, it has formed an aspect of cultural richness in Japanese culture. However, as a result, Japanese texts have intrinsically presented difficulties: not only in the case of textual analysis but also in both manual and automatic transcription in the digital era. This presentation will discuss problems in these writing systems and the current situation of attempts to resolve them through the methods of digital humanities.

1.1. Difficulties of transcription

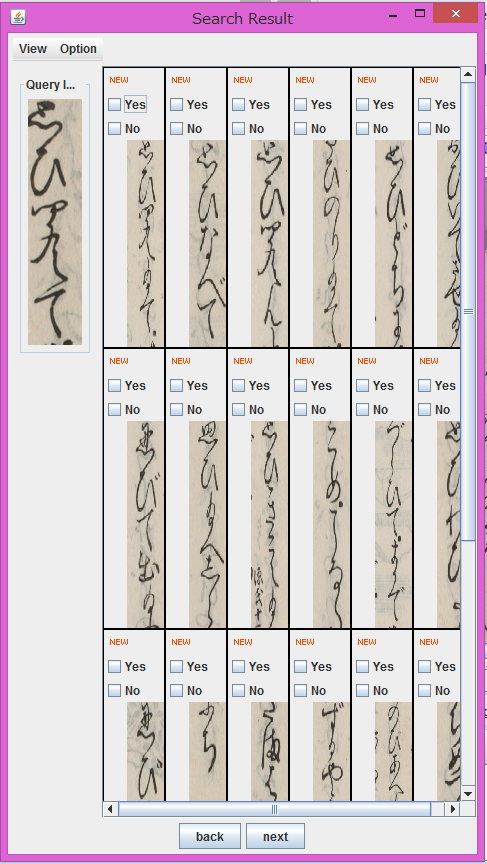

Recent Japanese texts do not have serious problem in case of OCR due not only to the separation of each character but also accuracy and clarify of its printing. However, it is difficult to OCR books printed even ten decades ago because of two points: most of them uses relatively complicated characters for OCR and parallel embedded small-font size texts (called ruby in HTML5) which explain pronunciation of a word, and are too close to the explained word to OCR (Fig. 3), even though they were printed by metal typesetting. More three decades ago characters were sometimes connected, and the writing style of characters were partially cursive (Fig. 4). Recently, some researchers are attempting to develop tools for recognition of kuzushi-ji not based on the shape of individual characters but by continuous shapes of characters. They have not yet reached the stage where they are able to transcribe all characters accurately, for both technical and intrinsic reasons, but the technology can nonetheless assist in reading such texts by showing candidates of characters (Fig. 5) 1. One of reasons why such kind of image recognition of a series of characters by machine is available in many cases is that many resources written by kuzushi-ji are woodcut printing, in which case the continuous cursive characters are more or less normalized within a single book.

However, there are special difficulties presented when a needed character is not encoded in Unicode. It seems to be similar with the case of Medieval Unicode Font Initiative 2, but the number of unencoded characters would be much more in the Japanese case included in East Asia culture. Especially, as Japanese culture has been involved with foreign cultures and developing them in its contexts, several writing systems are preserved in its cultural resources, including Kanji, Hiragana, Katakana, Hentaigana, and Siddham scripts. Siddham scripts were encoded in Unicode 8.0 with its variant characters by efforts of Script Encoding Initiative, international experts, and SAT project 3. There are already 80,000 Kanji (CJK unified characters) registered, but thus number will continue to increase. Hentaigana (including over 200 glyph shapes) was proposed to the ISO committee on October 2015 4. In order to make easy-use digital scholarly edition for Japanese texts, especially classics, this process will be continued.

While efforts of transcription, due to commoditization of digitizing textual materials in hi-resolution, digital image databases have also been grown in Japan. Especially, the National Diet Library in Japan has been addressing the publication of digitized collection including over 300,000 books--since over decades ago and recently stated that most of them are to be released in the public domain 5. And some institutes such as Kyoto Prefectural Library and Archives 6 and the University of Tokyo Library 7 are publishing their digitized collections under open license. The Art Research Center in Ritsumeikan University and the National Institute of Japanese Literature 8 have released many digitized textual resources under academic license. The latter institute plans to distribute parts of their contents under open license in this year in its new comprehensive digitization project 9. Needless to say, these are useful to enhance the convenience of humanities research. Especially, in Japanese contexts, many humanities researchers mention that validation of research results has been made much more efficient by the increased use of the digitized images.

Crowd sourcing transcription has recently emerged also in Japan. Transcribe JP project has been conducted as a SIG of the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities. It provides a Web service 10 for transcription with Omeka and Scripto plugin. Moreover, it started a micro task crowd sourcing project on 11 October 2015 in cooperation with Crowd4U project 12. Contributors can determine whether a character is exactly OCRed or not, comparing a candidate character with a piece of an image only by one click. The first experiment was finished in a much shorter time than we expected. Further results will be reported at the DH2016.

1.2. Difficulties in Word Separation

In spite of the difficulties of transcription, there are many digitized texts in Japanese. Aozora-Bunko 13, a public domain Japanese texts repository similar to the Gutenberg Project, provides over 10,000 texts on its Web site and GitHub. The National Institute of Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL) 14 publishes several encoded historical Japanese texts with POS tags on Web and Web services of textual analysis on modern Japanese texts including 100 million words with POS tags each word in its original format. The SAT project 15 also provides digital texts of Buddhist scriptures consists of 100 million characters mainly in Chinese and Japanese with some philological tags on Web.

The texts of NINJAL consists of separated words with POS tags, but most of the others do not use this method. Then, methods for textual analysis are common in Japan: The one is n-gram analysis regarded a character as one “n”. The other is developing tools for automatic separation of words sometimes with POS tagger, such as Mecab 16, Chasen 17, and Kuromoji 18. These tools realize a high degree of precision, but sometimes produce erros. In this case, one has to manually correct the result of the tools if sharing exactly-processed texts is necessary. Moreover, even if a separation is not mistaken, it might support an interpretation in some cases. Such kinds of cases can also be occurred in word-separated corpora. This type of writing system includes such kinds of issues.

1.3. Rendering of texts

In XML-formatted texts, suc has those maintained in TEI, JATS 19, and so on representation of breaks in source XML files seems to be regarded a space as a separation between words in popular stylesheets. But in the case of non-separated texts, it causes problems such as unnecessary separation. The XSLT-processed Japanese text in fig.7 must exclude spaces between characters in spite of line-breaks in the XML source (fig.6). Conversely, as a Japanese semi-governmental open access journal system adopting JATS ignores line breaks even in English, the words are connected in the case of Fig. 6 and Fig.7. This problem seems to be recognized in ePub with solution in CSS according to the target language 20. While it must already be discussed even in contexts of DH because non-spacing texts have been generated in various time and place, the differences of treatment of the line-breaks in XML source files should be carefully treated regarding not only representation but also analysis of texts.

In contexts of current DH, huge humanities resources have still been dormant. According to their awakening, these kind of issues should be gradually revealed and needed to be solved from both practical and abstract viewpoints. Through solving them earnestly under global communication, DH will come to better fruition.

Hashimoto, Yuta, et al. The SMART-GS Project: An Approach to Image-based Digital Humanities. Digital Humanities 2014:476-477. 2014.

http://folk.uib.no/hnooh/mufi/

Pandey, Anshuman. Proposal to Encode the Siddham Script in ISO/IEC 10646. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4294. 2012. http://www.unicode.org/L2/L2012/12234r-n4294-siddham.pdf .

KAWABATA , Taichi, Toshiya SUZUKI, Kiyonori NAGASAKI and Masahiro SHIMODA. Proposal to Encode Variants for Siddham Script. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4407. 2013. http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/n4407.pdf .

Anderson, Deborah, et al. 2013-11-22 Siddham Script (梵字) Meeting @ Tokyo, JAPAN, Earth. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4523. 2013. http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/n4523.pdf .

ITSCJ SC2 Committee, IPSJ, JAPAN. Proposal of Japanese HENTAIGANA. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4674. 2015. http://unicode.org/wg2/docs/n4674-Japan_Hentaigana_Proposal-a.zip .

http://dl.ndl.go.jp/

http://hyakugo.kyoto.jp/

http://dzkimgs.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/utlib_kakouzou.php

http://www.nijl.ac.jp/

http://www.nijl.ac.jp/pages/cijproject/index_e.html

Hondigi2014. http://lab.ndl.go.jp/dhii/omk2/

翻デジ@JADH×Crowd4U. http://www.jadh.org/transcribejp

Crowd4U. http://crowd4u.org/en/

http://www.aozora.gr.jp/

http://www.ninjal.ac.jp/

http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/

http://taku910.github.io/mecab/

http://chasen.naist.jp/hiki/ChaSen/

http://www.atilika.com/ja/products/kuromoji.html

http://jats.nlm.nih.gov/