Authors: Angelo Mario Del Grosso, Davide Albanesi, Emiliano Giovannetti, Simone Marchi

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: Literary Computing, Textual Processing, Object-Oriented Analysis and Design, Analysis Architectural and Design Patterns, Web infrastructure

Defining the Core Entities of an Environment for Textual Processing in Literary Computing

1. Introduction

The development of applications in the field of Digital Humanities (DH) does not adequately take into account domain modelling, software design principles and software engineering methodologies (Bozzi, 2013; D'Iorio, 2015; McCarty, 2008; Terras and Crane, 2010). In fact, many systems developed in the context of DH-related projects have not been conceived to be modular, extensible, and scalable: they only tend to solve specific problems such as data-driven and project-oriented tools (Boschetti and Del Grosso, 2015). In addition, most projects focus on the requirements of humanists (as end users), but leave out the needs of software developers.

This research was motivated by a number of issues emerged from the projects we worked on (Abrate et al., 2014a; Albanesi et al., 2015; Bellandi et al., 2014; Bozzi, 2015; Del Grosso, 2013; Ruimy et al., 2012) and it fits into an ongoing discussion about textual modelling and research infrastructures (Moulin et al., 2011; Pierazzo, 2015; Schmidt, 2014). In particular, this work aims at providing methodological guidelines for the definition of the core entities of a digital scholarly environment. We chose to adopt an object-oriented approach since it can bring benefits in the definition of efficient and effective digital tools (Boschetti et al., 2014; Del Grosso and Nahli, 2014). To give an analogy, the environment we propose can help developers and scholars as CMS (e.g. Wordpress) can help Web designers and publishers.

The development of the environment follows three criteria: i) adopting an agile process (Ashmore and Runyan, 2014) to define the nature and behavior of the environment through both functional (e.g. user stories) and non-functional requirements (e.g. data model, system architecture) (Cohn, 2004; Collins-Cope et al., 2005); ii) providing well-defined Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) among components (Grill et al., 2012; Tulach, 2008); iii) applying analysis, architectural and design patterns for the sake of abstraction, generalization and flexibility (Ackerman and Gonzalez, 2011; Buschmann et al., 2007; Gamma et al., 1995).

Following the agile methodology, we are developing a modular environment by starting from the design and implementation of a microkernel (Buschmann et al., 1996) as the manager of the different components. In addition, the microkernel provides all the operations needed to manipulate the domain basic entities which are described in the section “Domain entities and design patterns”.

1.1. Related works

Digital humanists have access to several tools for literary studies. TextGrid, for example, provides integrated tools for analyzing texts and gives computer support for digital editing purposes (Hedges et al., 2013). The NINES project offers an environment to support scholars in the creation of long-term digital research materials. It includes three main tools: Collex (Nowviskie, 2007), Juxta, and Ivanhoe. Annotation Studio is a collaborative system to annotate texts and add links to multimedia objects (Paradis et al., 2013). The CULTURA project aims at developing a “corpus agnostic research environment” providing customizable services for a wide range of users (Steiner et al., 2014). The development of an online workspace which helps scholars in the production of critical editions is the main objective of the Workspace for Collaborative Editing framework (Houghton et al., 2014). It uses existing standards and open-source solutions to create an architecture of reusable components. Other platforms worth mentioning are TUSTEP/TXSTEP (Ott, 2000; Ott and Ott, 2014), WebLicht (Hinrichs et al., 2010), Perseids (Almas and Beaulieu, 2013), Muruca/Pundit (Grassi et al., 2013), Textual Communities (Bordalejo and Robinson, 2015), SAWS (Jordanous et al., 2012), Voyant Tools (Sinclair and Rockwell, 2012), Transcribe Bentham (Causer and Terras, 2014) and Alcide (Moretti et al., 2014). However, the aforementioned initiatives allow digital scholars to meet specific needs, but none of them seems to provide, simultaneously, all the following characteristics: i) reusability and extensibility, ii) ease of use and configuration, iii) continuous availability of the services and development over time, iv) a well-grounded software data model.

2. Domain entities and design patterns

One of the main challenges of the DH community is to provide suitable software models and tools (Ciotti, 2014). To model the literary domain and the relative user requirements, we chose to follow the engineering principles of object-oriented analysis and design (Ackerman and Gonzalez, 2011). The digital representation of a textual resource is a challenge as it involves several theoretical and epistemological issues in semiotics, paleography, philology, linguistics, engineering, and computer science (McCarty, 2005; Meister, 2012; Moretti, 2013; Robinson, 2013; Sahle, 2013).

In this work, we define each textual element by means of four properties: i) the version allows to select a specific textual element among those available in its history of changes; ii) the granularity represents a level of a hierarchical structure (e.g. a page composed of lines); iii) the position provides the location of a textual element within the hierarchical representation (e.g. the second page of a book); iv) the layer indicates the set of homogeneous information the textual element belongs to (e.g. morphological layer). As pointed outby (Buzzetti, 2002; McGann, 2004; Pierazzo, 2015), the information conveyed by a textual resource is logically organized through multiple layers (also called dimensions) of information.

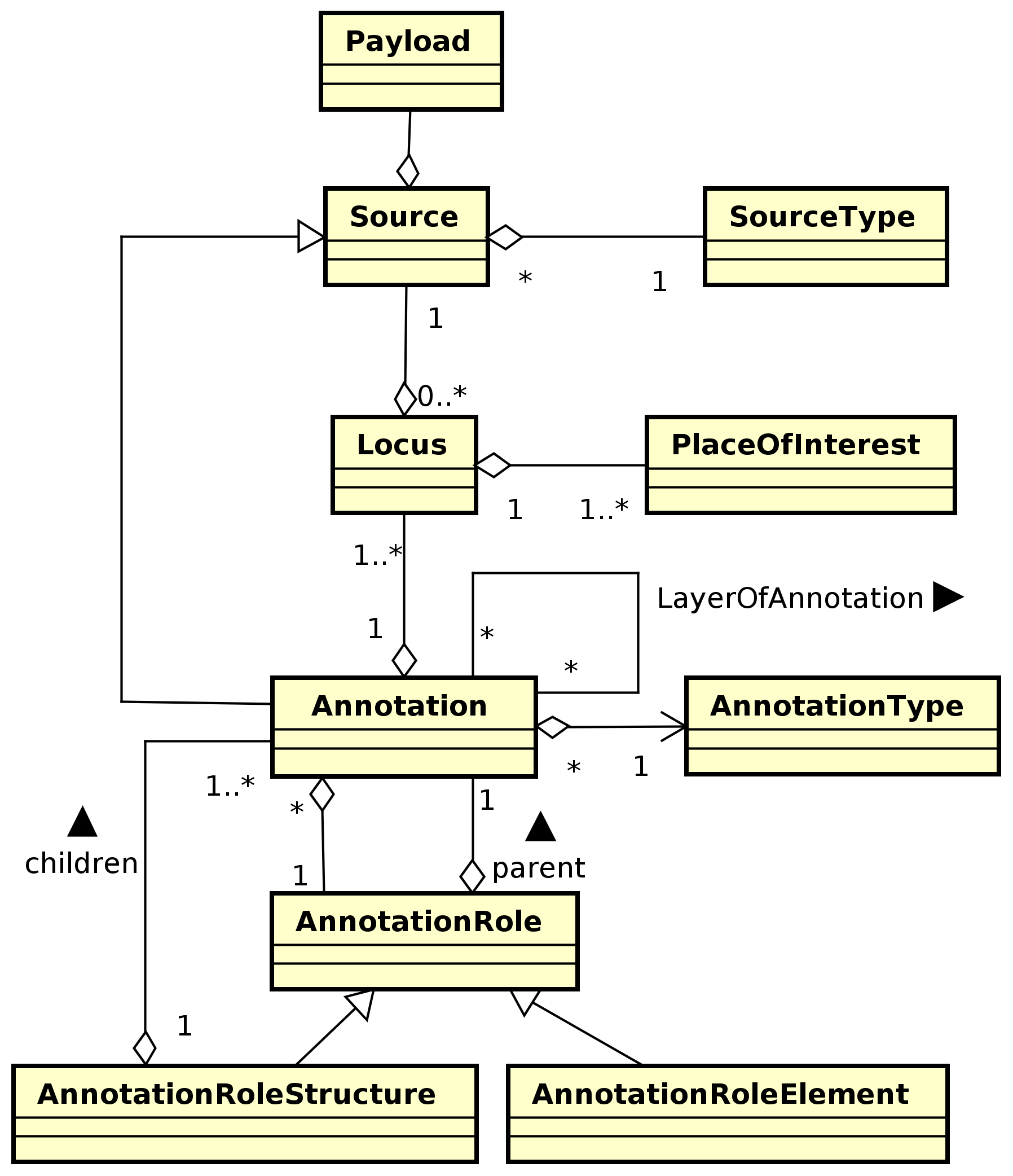

On these four properties we have designed and implemented a set of core entities as the fundamental data types shared among all the components of the environment (Fig. 1) 1. The Source class is in charge of managing the low-level data: it is composed of a Payload representing the information conveyed by the textual resource and a SourceType which indicates the nature of the Source (e.g. text, image, audio, etc.). Payload objects (as used in networking) have the only purpose of encapsulating the information. The Locus and the P lace OfInterest (POI) classes identify, through a composition pattern, specific data fragments of the source content, and they are used to establish the boundaries of an Annotation. A chunk of text, for example, can be addressed to by a locus having a POI (of type Sequence of Interest) representing its start and end coordinates. Similarly, a region of an image can be identified by a locus having a POI (of type Region of Interest) composed of a sequence of coordinates. The Locus and POI provide a stand-off text annotation technique able to tackle, for example, the overlapping hierarchies problem, which cannot be handled easily with inline markup techniques (Schmidt, 2010). As a matter of fact, it is possible, simultaneously, to manipulate a resource on the basis of its documental and textual structure (Renear et al., 1996; Robinson, 2013) (see the example in the following section). However, since stand-off models are affected by the issue of the indexing updating, a dedicated component must be in charge of automatically maintaining the coherence of the annotations each time the underlying text is edited.

An Annotation represents an information associated to a locus and is defined by an AnnotationType (e.g. a token, a lemma, a named entity, etc.). Since the hierarchical structure of the source may evolve over time, the changes to the relative tree must be managed. For example, a tree structure having tokens as leaves could need to be updated with a finer-grained layer of characters (e.g. to assign annotations to specific letters). In this case, the tokens should become intermediate nodes and the characters would become the leaf nodes. Typically, this kind of editing is unpredictable and it often implies heavy adaptations if the software is not flexible enough to manage changes in the underlying text representation schema. Consequently, we decided to exploit the flexibility of the Object Oriented model by adopting the Role Design Pattern (Fowler, 1997) to switch between leaf and intermediate nodes dynamically. This pattern has been implemented by the AnnotationRole, AnnotationRoleElement and AnnotationRoleStructure classes. Moreover, an annotation is a source in itself (see the inheritance relationship between the Annotation and the Source classes in Fig. 1) and, thus, it can be annotated recursively.

3. An Example

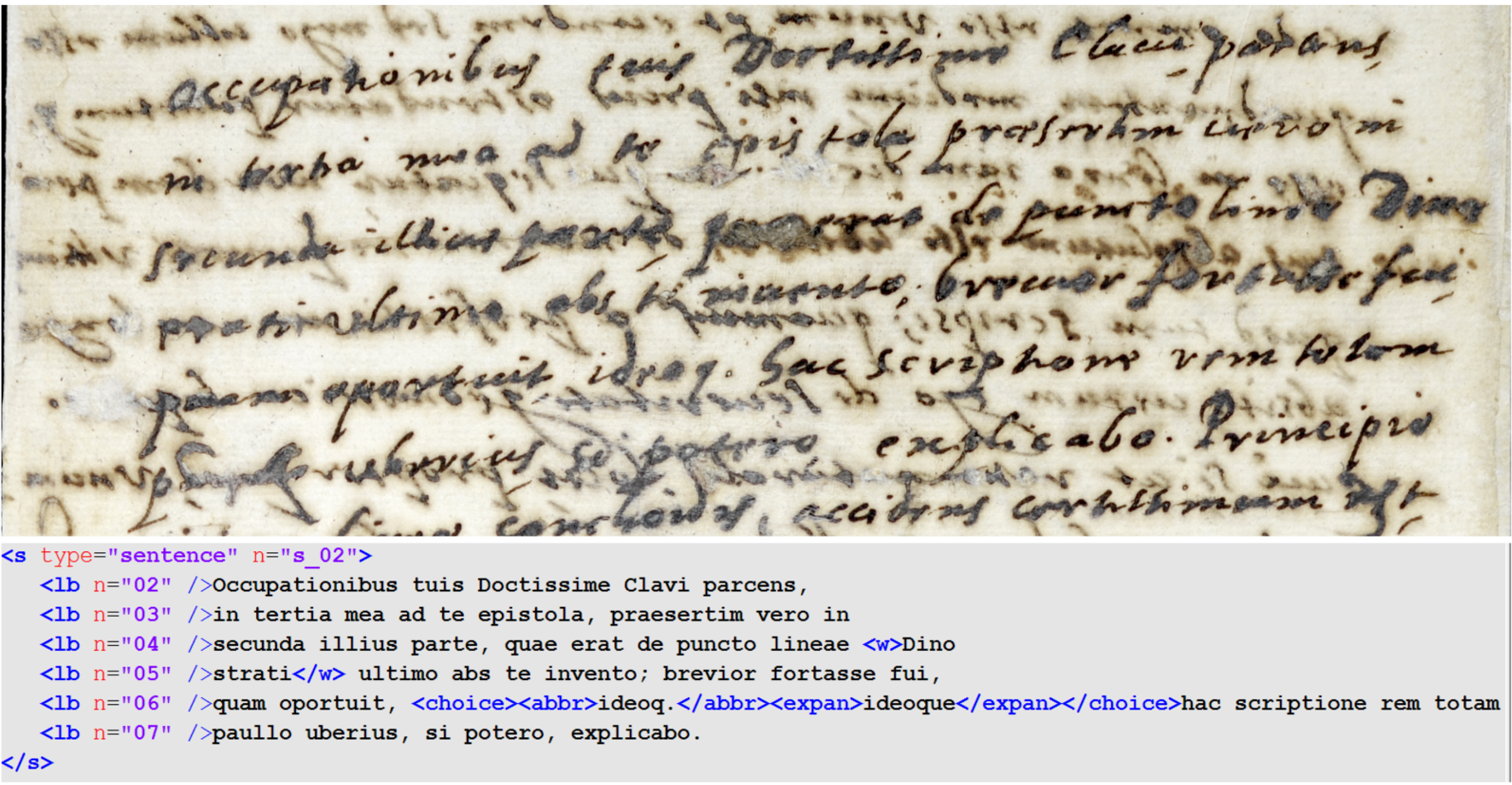

We here introduce an example showing a representation of a snippet of text with annotations. The chosen text is an excerpt of a letter, written in Latin, belonging to the epistolary corpus of the Clavius on the Web project 2 (Abrate et al., 2014b). Fig. 2 shows a typical way of encoding sentences and lines with a markup language as TEI (Burnard, 2014): the resulting XML hierarchical structure has been broken by the addition of the line anchors (<lb />) mixing up the textual and documental structure of the text. Indeed, to preserve the integrity of the word “Dinostrati” (spanning across lines 4 and 5), it is necessary to encapsulate it with the element <w />.

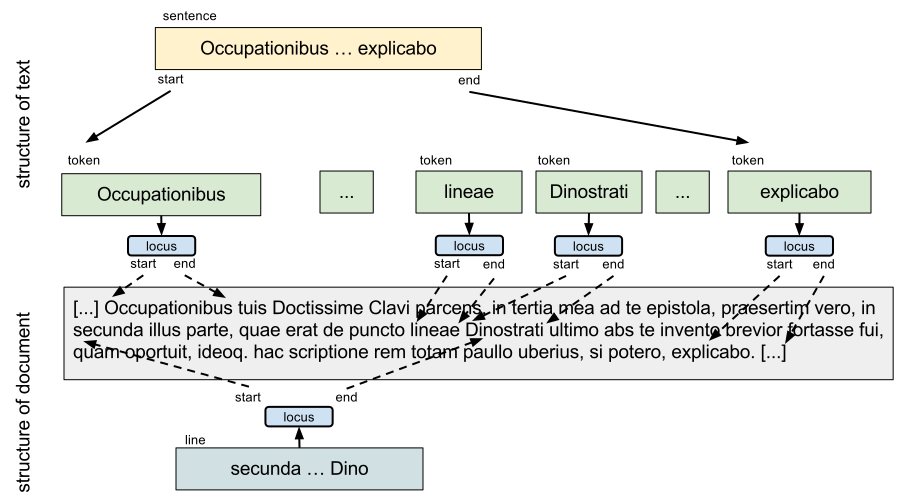

The model we propose solves this problem with the stand-off annotations: as shown in Fig. 3 the document (made of lines) and the textual structure (made of sentences and words) are logically separated. Lines, sentences and words do not overlap and they are structured in separate hierarchies.

4. Next Steps

We plan, in future works, to release a first version of a web environment, called Omega, built around the core entities that we here described. The environment will allow to load, index, annotate, and query a textual collection. Furthermore, we’ll carry on the development of modules for text analysis and textual scholarship with the related APIs.

- Abrate, M., Del Grosso, A. M., Giovannetti, E., Lo Duca, A., Luzzi, D., Mancini, L., Marchetti, A., Pedretti, I. and Piccini, S. (2014a). Sharing Cultural Heritage: the Clavius on the Web Project. In Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Loftsson, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Moreno, A., Odijk, J. and Piperidis, S. (eds), Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC), Reykjavik. European Language Resources Association (ELRA), pp. 627–34.

- Abrate, M., Del Grosso, A. M., Giovannetti, E., Lo Duca, A., Marchetti, A., Mancini, L., Pedretti, I. and Piccini, S. (2014b). Il Progetto Clavius on the Web: tecnologie linguistico-semantiche al servizio del patrimonio documentale e degli archivi storici. In Rossi, F. and Tomasi, F. (eds), Book of Abstracts of 3 o AIUCD Conference, Bologna.

- Ackerman, L. and Gonzalez, C. (2011). Patterns-Based Engineering: Successfully Delivering Solutions Via Patterns. Addison-Wesley.

- Albanesi, D., Bellandi, A., Benotto, G., Di Segni, G. and Giovannetti, E. (2015). When Translation Requires Interpretation: Collaborative Computer–Assisted Translation of Ancient Texts. LaTeCH 2015: 84–88.

- Almas, B. and Beaulieu, M.-C. (2013). Developing a New Integrated Editing Platform for Source Documents in Classics. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 28(4): 493–503 doi:10.1093/llc/fqt046.

- Ashmore, S. and Runyan, K. (2014). Introduction to Agile Methods. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley Professional, Pearson Education.

- Bellandi, A., Albanesi, D., Bellusci, A., Bozzi, A. and Giovannetti, E. (2014). The Talmud System: a Collaborative web Application for the Translation of the Babylonian Talmud Into Italian. The First Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics CLiC-It 2014, pp. 53–57.

- Bordalejo, B. and Robinson, P. (2015). A new system for collaborative online creation of Scholarly Editions in digital form. 1st Dixit Convension on Technology, Software, Standards for the Digital Scholarly Edition Workshop. The Hague.

- Boschetti, F. and Del Grosso, A. M. (2015). TeiCoPhiLib: A Library of Components for the Domain of Collaborative Philology. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative(8). doi:10.4000/jtei.1285. http://jtei.revues.org/1285 (accessed 3 March 2016).

- Boschetti, F., Del Grosso, A. M., Khan, A. F., Lamé, M. and Nahli, O. (2014). A top-down approach to the design of components for the philological domain. Book of Abstract of Digital Humanities Conference (DH), Lausanne, Switzerland. Alliance of Digital Humanities Organisations, pp. 109–11.

- Bozzi, A. (2013). G2A: A Web application to study, annotate and scholarly edit ancient texts and their aligned translations. (Ed.) ERC Ideas 249431 Studia Graeco-Arabica, 3: 159–71.

- Bozzi, A. (2015). Greek into Arabic, a research Infrascructure based on computational modules to annotate and query historical and philosophical digital texts. Part I: Methodological aspects. In Bozzi, A. (ed), Digital Texts, Translations, Lexicons in a Multi-Modular Web Application: Methods and Samples. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki editore, pp. 27–42.

- Burnard, L. (2014). TEI P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Version 2.9.1. http://www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/P5/index.xml (accessed 3 March 2016).

- Buschmann, F., Henney, K. and Schmidt, D. C. (2007). Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture, On Patterns and Pattern Languages. (Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Buschmann, F., Meunier, R., Rohnert, H., Sommerlad, P. and Stal, M. (1996). Pattern-oriented Software Architecture - A System of Patterns. J. Wiley and Sons Ltd., pp. 171–92.

- Buzzetti, D. (2002). Digital Representation and the Text Model. New Literary History, 33(1): 61–88.

- Causer, T. and Terras, M. (2014). “Many hands make light work. Many hands together make merry work”: Transcribe Bentham and crowdsourcing manuscript collections.

- Ciotti, F. (2014). Digital Literary and Cultural Studies: State of the Art and Perspectives. Between, 4(8). doi:10.13125/2039-6597/1392. http://dx.doi.org/10.13125/2039-6597/1392 (accessed 3 March 2016).

- Cohn, M. (2004). User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development. Redwood City, CA, USA: Addison Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.

- Collins-Cope, M., Rosenberg, D. and Stephens, M. (2005). Agile Development with ICONIX Process: People, Process, and Pragmatism. Berkely, CA, USA: Apress.

- Fowler, M. (1997). Dealing with roles. Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs, vol. 97, pp. 13–37.

- Gamma, E., Helm, R., Johnson, R. and Vlissides, J. (1995). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Boston, MA, USA: Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.

- Grassi, M., Morbidoni, C., Nucci, M., Fonda, S. and Piazza, F. (2013). Pundit: augmenting web contents with semantics. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 28(4): 640–59.

- Grill, T., Polacek, O. and Tscheligi, M. (October 29-312012). Methods Towards API Usability: A Structural Analysis of Usability Problem Categories. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Human-Centered Software Engineering, Toulouse, France. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, pp. 164–80. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-34347-6_10.

- Del Grosso, A. M. (2013). Indexing techniques and variant readings management. (Ed.) D'Ancona, C. Studia Graeco-Arabica, 3: 209–30.

- Del Grosso, A. M. and Nahli, O. (2014). Towards a flexible open-source software library for multi-layered scholarly textual studies: An Arabic case study dealing with semi-automatic language processing. Proceedings of 3rd IEEE International Colloquium, Information Science and Technology (CIST), Tetouan, Marocco. Washington, DC, USA: IEEE, pp. 285–90. doi:10.1109/CIST.2014.7016633.

- Hedges, M., Neuroth, H., Smith, K. M., Blanke, T., Romary, L., Küster, M. and Illingworth, M. (2013). TextGrid, TEXTvre, and DARIAH: Sustainability of Infrastructures for Textual Scholarship. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative(5). doi:10.4000/jtei.774 (accessed 3 March 2016).

- Hinrichs, E., Hinrichs, M. and Zastrow, T. (2010). WebLicht: Web-based LRT services for German. Proceedings of the ACL 2010 System Demonstrations. Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 25–29.

- Houghton, H., Sievers, M. and Smith, Catherine (2014). The Workspace for Collaborative Editing. Digital Humanities 2014. Laussanne: Alliance of Digital Humanities Organisations, pp. 204–05.

- D' Iorio, P. (2015). On the scholarly use of the Internet, a conceptual model. In Bozzi, A. (ed), Digital Texts, Translations, Lexicons in a Multi-Modular Web Application: Methods and Samples. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki editore, pp. 1–25.

- Jordanous, A., Lawrence, K. F., Hedges, M. and Tupman, C. (June 13-152012). Exploring Manuscripts: Sharing Ancient Wisdoms Across the Semantic Web. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Web Intelligence, Mining and Semantics (WIMS), Craiova, Romania. New York, NY, USA: ACM, pp. 44:1–44:12. doi:10.1145/2254129.2254184.

- McCarty, W. (2005). Humanities Computing. Palgrave Macmillan.

- McCarty, W. (2008). Signs of times present and future. Human Discussion Group, 22(218).

- McGann, J. (2004). Marking Texts of Many Dimensions. In Schreibman, S., Siemens, R. and Unsworth, J. (eds), A Companion to Digital Humanities. (Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture). Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 198–217.

- Meister, J. C. (2012). DH is us or on the unbearable lightness of a shared methodology. Historical Social Research, 37(3): 77–85.

- Moretti, F. (2013). Distant Reading. Verso Books.

- Moretti, G., Tonelli, S., Menini, S. and Sprugnoli, R. (2014). ALCIDE: An online platform for the Analysis of Language and Content In a Digital Environment. Proceedings of the First Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics (CLIC-2014). Pisa, Italy.

- Moulin, C., Nyhan, J., Ciula, A., Kelleher, M., Mittler, E., Tadić, M., Ågren, M., Bozzi, A. and Kuutma, K. (2011). Research Infrastructures in the Digital Humanities. http://www.esf.org/hosting-experts/scientific-review-groups/humanities-hum/strategic-activities/research-infrastructures-in-the-humanities.html.

- Nowviskie, B. (2007). Collex: Facets, Folksonomy, and Fashioning the Remixable web. Book of Abstract of Digital Humanities Conference (DH), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Alliance of Digital Humanities Organisations.

- Ott, W. (2000). Strategies and tools for textual scholarship: the Tübingen system of text processing programs (TUSTEP). Literary and Linguistic Computing, 15(1): 93–108. doi:10.1093/llc/15.1.93. http://llc.oxfordjournals.org/content/15/1/93.abstract.

- Ott, W. and Ott, T. (2014). Critical Editing with TXSTEP. In Terras, M. (ed), Book of Abstracts of the Digital Humanities Conference, Lausanne, Switzerland. Alliance of Digital Humanities Organisations, pp. 509–13.

- Paradis, J., Fendt, K., Kelley, W., Folsom, J., Pankow, J., Graham, E. and Subbaraj, L. (2013). Annotation Studio: Bringing a Time-Honored Learning Practice into the Digital Age. Whitepaper. http://cmsw.mit.edu/annotation-studio-whitepaper/ (accessed 3 March 2016).

- Pierazzo, E. (2015). Digital Scholarly Editing : Theories, Models and Methods. Farnham Surrey: Ashgate.

- Renear, A. H., Mylonas, E. and Durand, D. (1996). Refining our notion of what text really is: The problem of overlapping hierarchies. (Ed.) Hockey, S. M. Research in Humanities Computing, 4: 263–80.

- Robinson, P. (2013). Towards a theory of digital editions. (Ed.) Mierlo, W. V. and Fachard, A. Variants, (10): 105–31.

- Ruimy, N., Piccini, S. and Giovannetti, E. (2012). Defining and Structuring Saussure’s Terminology. In Fjeld, R. V. and Torjusen, J. M. (eds), Proceedings of 15th EURALEX International Congress. Oslo, Norway, Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies, University of Oslo, Reprosentralen: UiO press, pp. 828–33.

- Sahle, P. (2013). Digitale Editionsformen: Teil 3: Textbegriffe Und Recodierung; Zum Umgang Mit Der Überlieferung Unter Den Bedingungen Des Medienwandels. Vol. 3. BoD–Books on Demand.

- Schmidt, D. (2010). The inadequacy of embedded markup for cultural heritage texts. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 25(3): 337–56. doi:10.1093/llc/fqq007.

- Schmidt, D. (2014). Towards an Interoperable Digital Scholarly Edition. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative(7). doi:10.4000/jtei.979.

- Sinclair, S. and Rockwell, G. (2012). the Voyant Tools Team (web application) Voyant Tools. http://voyant-tools.org (accessed 3 March 2016).

- Steiner, C., Agosti, M., Sweetnam, M., Hillemann, E.-C., Orio, N., Ponchia, C., Hampson, C., et al. (2014). Evaluating a digital humanities research environment: the CULTURA approach. International Journal on Digital Libraries, 15(1): 53–70. doi:10.1007/s00799-014-0127-x.

- Terras, M. and Crane, G. (eds). (2010). Changing the Center of Gravity: Transforming Classical Studies through Cyberinfrastructure. Piscataway: Gorgias Press.

- Tulach, J. (2008). Practical API Design: Confessions of a Java Framework Architect. 1st ed. Berkely, CA, USA: Apress.