Authors: David L. Hoover

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: character dialogue, computational stylistics, text-analysis

Microanalyzing Parts of Texts

Some broad questions require the analysis of huge collections of texts. Other broad questions and many narrower ones require microanalyzing parts of texts. Some microanalyses are unproblematic: narrative structure and its relationship to chapter divisions can be studied simply by dividing texts into chapters. Analyzing narrative or dialogue only, or the relationships between these and chapter divisions, may be much more problematic, as may analyzing a novel that also contains letters, diaries, legends, and poetry. Some or all of these may be more appropriately analyzed separately or ignored. Difficulties multiply for multiple narrators whose narratives contain dialogue and subdivisions.

One of the most difficult tasks is analyzing the character dialogue in a novel. Burrows showed that the frequencies of the most frequent words in their dialogue can distinguish Jane Austen’s characters from each other (1987), but few scholars have followed his lead, at least partly because of the tedium and difficulty of separating character parts. McKenna and Antonia (1996) were an early exception, but most related work involves epistolary novels or multiple narrators, where the separation of parts is simpler (Stewart 2003; Rybicki 2006; Ramsay 2011; Balossi 2014; Hoover, Culpeper, and O’Halloran 2014; Hoover 2010, and forthcoming).) Consider the case of Sherlock Holmes. Perhaps, as Moretti argues, “Doyle owes his phenomenal success to his greater skill in the handling of clues” (2004, 48), but Holmes and Watson are also extraordinarily fascinating characters. Analyzing their voices for distinctiveness requires comparing them with his other characters. Because reliable results require substantial amounts of text, I focus here on the longest Holmes novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles ( Hound, below).

Extracting the dialogue computationally still requires the tedious and error-prone manual separation of the character parts and identification of the speakers. Typically characters are too numerous to open separate dialogue files for all of them, and multiple files increase copying and pasting errors. Initial decisions about the handling of dialogue may also change, requiring painstaking re-editing. Instead, I introduce very simple markup that is then processed in “Analyze Textual Divisions,” an Excel spreadsheet with macros. The markup, powerful enough for texts with quite complex structures, is also simple, flexible, and customizable:

<1> text division 1

<2> text division 2

<3> text division 3

<4> text division 4

[ ] Letter writer

{ } Letter addressee

/ speaker

\ speech marker

> copy without processing

^ special character follows

For Wilkie Collins’s complex novel No Name, with scenes containing chapters, which contain letters and other documents, the four divisions are “Scene”, “Chapter”, “Letter”, and “Document.” (The spreadsheet includes brief excerpts from this novel with mark-up.) Epistolary novels might use “Letter,” and others might use “Volume” and “Book.” For texts with multiple narrators and for plays “Narrator” and “Act” and “Scene” are obvious divisions. The top-level division, like the rest of the markup, can be modified. For No Name, division one is defined as follows: div1name = “Scene”. Novels divided into books could use “div1name = “Book.” Alternatively, after the macro operates, the labels can be changed as desired.

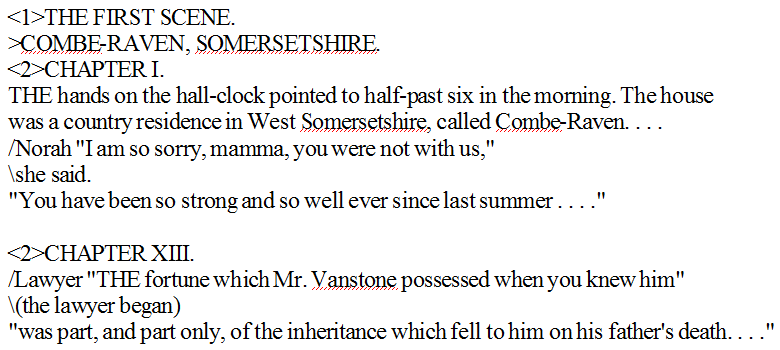

Here is a truncated version of No Name:

A “<1>” has been inserted to mark “THE FIRST SCENE.” as division one, and all lines in the first scene will be so labeled. In line two, “>” indicates that “COMBE-RAVEN, SOMERSETSHIRE.,” which seems like a scene-setting label, not narrative, should not be processed (epigraphs or poems might be treated similarly). In line three, “CHAPTER I.” marks division two. In line six, “/Norah” labels lines 6-8 as hers (the person addressed could, like a letter addressee, be marked with {}). In line seven, “\she said” is a speech marker, categorized separately because they sometimes vary interestingly and because “she said” seems to me neither dialogue nor narration. In line eight, the quotation mark indicates dialogue. The blank ninth line changes the label from dialogue to narrative until marked otherwise. The beginning of chapter thirteen is marked similarly. Later in the novel, embedded letters are marked with “Letter writer” and “Letter addressee.” Finally, “^” must begin any line that would otherwise begin with “+”, “-”, or “=” (reserved characters in Excel). (Line-division can be changed instead, except where required line breaks force special characters to the beginning.)

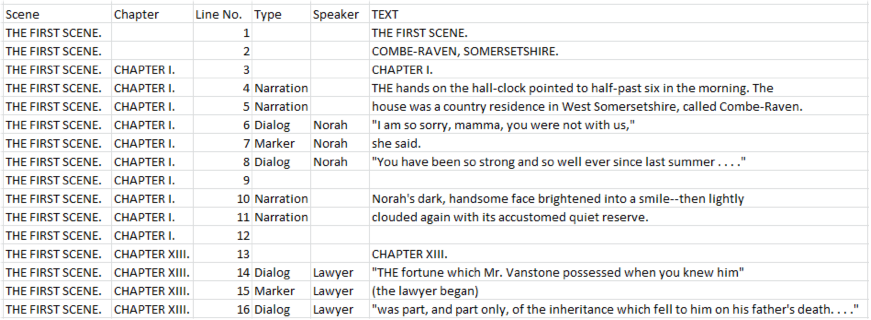

With the Analyze Textual Divisions spreadsheet and the marked-up text open in Excel, the macro processes the text line by line, producing the results below (the marked-up text and empty columns have been deleted). Each line gets a scene label, and, beginning in line three, a chapter label, and all the lines are numbered. Lines 4-5 are marked as narration, lines 6 and 8 as Dialogue, and line 7 as Marker, and the speaker is entered for lines 6-8 and 14-16. The processed text appears on the right with all markup removed.

The text could be marked up in TEI and the character parts extracted with XSLT, but the markup here is much simpler and easier to learn, and the spreadsheet has advantages over XSLT. Excel’s built-in sorting function can handle several levels of sorting, for example, so that the dialogue can be sorted by type, scene, chapter, speaker, and line number, all at once. The unmarked processed text, after sorting, can be divided and analyzed however the analyst desires with plain-text tools. Sorting on the line number restores the original order for further analysis, and errors can be corrected in the original text, and the analysis re-run. (See my Excel Text-Analysis Pages at http://wp.nyu.edu/exceltextanalysis/ for detailed instructions.) This method works especially well for short, simple texts like Hound, with character parts too short to be analyzed by chapter; the dialogue can be marked with just speaker and speech marker characters, and > and ^.

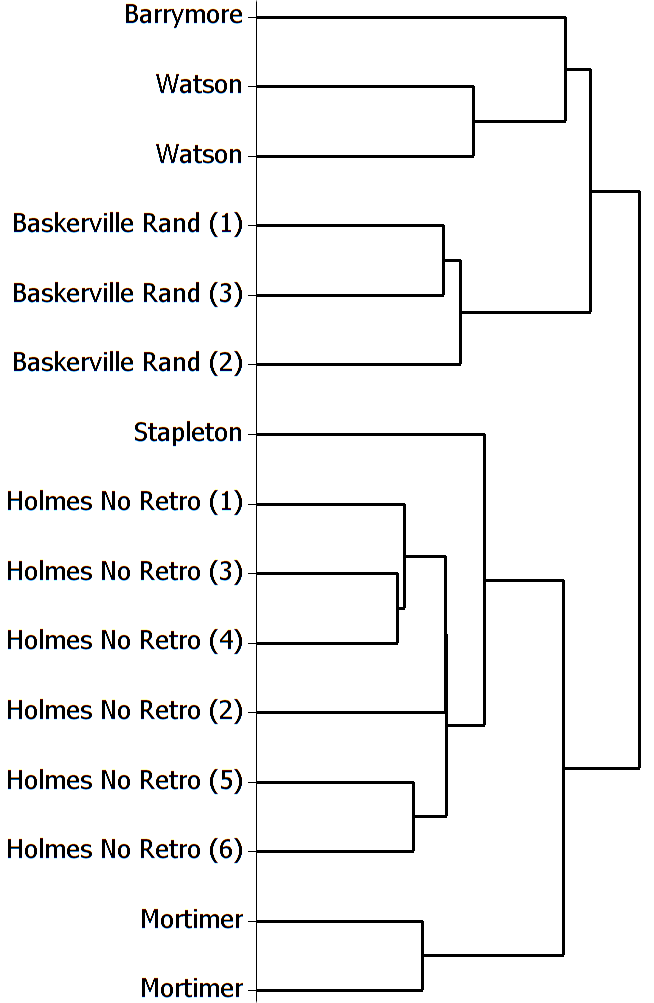

To test the distinctiveness of the character voices in Hound, I selected all character parts at least 1,500 words long, and divided longer parts into 1,500-word sections. Initial testing was disappointing. Although the sections of dialogue by Stapleton, Mortimer, and Watson grouped correctly, those by Baskerville, Barrymore, and Holmes did not, casting doubt on the distinctiveness of their voices. The section of Baskerville’s dialogue that groups with Barrymore’s, however, consists almost entirely of a conversation between the two, so that similarity of topic may skew the results. More significantly, the first six sections of Holmes’s dialogue consistently group correctly. The final two, which consist almost entirely of the final chapter, and which tend to group separately from all others, are Holmes’s explanation of the case to Watson. Nominally dialogue, this chapter is more like narration, a genre difference that is almost certainly responsible for the anomalous clustering. Removing the final chapter and sorting the lines of Baskerville’s dialogue in random order to blunt any topical or thematic effects produces the cluster analysis shown in Fig. 1, based on the 225mfw (most frequent words).

Cluster analysis is an exploratory statistical method that compares the frequencies of a set of words across a set of texts to determine which texts use those words at the most similar frequencies. The nearer to the left that sections join together into a single cluster, the more similarly they use the words. All sections in Fig. 1 group correctly by speaker, and several sections of Holmes’s dialogue are the most similar, and the results are correct across analyses based on the 125-325mfw. Doyle’s use of clues may have helped the Sherlock Holmes stories succeed, but the distinct character voices also seem likely to be a factor. (The analysis here uses Ward Linkage and squared Euclidean distance; the often-used complete linkage gives weaker results.)

Separating character dialogue can never be easy, but my spreadsheet makes it much easier. It also provides a versatility in comparing multiple kinds of textual divisions that may encourage more in-depth analysis of dialogue and characterization and enhance our understanding of how texts work.

- Balossi, G. (2014). A Corpus Linguistic Approach to Literary Language and Characterization: Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. Amsterdam: Johns Benjamins.

- Burrows, J. (1987). Computation into Criticism. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hoover D. (forthcoming). Argument, evidence, and the limits of digital literary studies. In Gold, M. (ed), Debates in the Digital Humanities, University of Minnesota Press.

- Hoover D. (2010). Some approaches to corpus stylistics. In Yu Dongmin (ed), Stylistics: Past, Present and Future. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, pp. 40-63.

- Hoover, D., Culpeper, J., and O’Halloran, K. (2014). Digital Literary Studies: Corpus Approaches to Poetry, Prose, and Drama. London: Routledge.

- McKenna, C. W. F., and Antonia, A. (1996). ‘A few simple words’ of interior monologue in “Ulysses”: reconfiguring the evidence. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 11(2): 55-66.

- Moretti, F. (2004). Graphs, maps, trees: abstract models for literary history — 3, New Left Review, 28: 43-63.

- Ramsay, S. (2011). Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Rybicki, J. (2006). Burrowing into translation: character idiolects in Henryk Sienkiewicz’s trilogy and its two English translations. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 21(1): 91-103.

- Stewart, L. (2003). Charles Brockden Brown: quantitative analysis and literary interpretation. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 18(2): 129-38.