Authors: Mihnea Tufis

Category: Paper:Short Paper

Keywords: crowdsourcing, comics, annotation, data quality

Adding Semantics To Comics Using A Crowdsourcing Approach

1. Introduction

With over 85 million print units sold in 2014 for the top 300 comic book titles only, the comics industry is reaching a new high for the first time since 2007 (before the economical crisis). And this doesn’t include the increasingly popular graphic novels or the increasingly more accessible digital comics. The resurgence of comics and the establishment of the graphic novel as a literary genre prompted Humanities scholars to turn their attention on comics as a medium. In this paper, we address the difficulty of creating a digitized corpus by using a crowdsourced approach for annotating comic books. The resulting XML-based encodings could assist not only researchers, but publishers and collection curators equally.

2. Motivation

Our approach should provide Digital Humanities (DH) scholars with a (currently missing) structured, annotated corpus; this should enable or speed up research related to the comics and sequential art theory: identifying the rhythm of the narration based on the shape, size or number of panels and its relation to the depicted action, investigations about the style of comics authors, historical periods, cultural movements etc.

Curators and collectors (professional or amateur) of physical or online comics collections would be provided with a structured content which could be more easily integrated within their collections or databases. This may assist them into enlarging public or private databases of characters or comics series and enable the creation of artefacts such as comic books dictionaries, search indices and dictionaries of onomatopoeia. A certain number of projects are already in place and could greatly benefit from the creation of comic books annotations. We mention here the Grand Comics Database 1 (an online database of printed comics), Comic Book Database 2, Digital Comics Museum 3 (a collection of scanned public domain comics from the Golden Age) or the Catalogue of the Cité Internationale de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image 4 from Angoulême.

From a publishing perspective, current standard specifications related to digital comics, such as EPUB’s Region Based Navigation (Conboy et al., 2014) and Metadata Structural Vocabulary for Comics (Ichikawa et al., 2014) are taking care exclusively of the presentation layer (i.e. rendering a publication on a screen device). But the artistic nature of comics and the great potential digital comics have already showcased allow us to go beyond simple content presentation. We believe that the data we are collecting will allow publishers and digital comics authors to create better, enhanced content and in the end a superior reading experience.

3. Crowdsourcing Annotations for Comics

Participants to our crowdsourcing experiment (Azavea, 2014; Sharma, 2010) are digital comics readers. Previous research has identified expertise sharing, belonging to a community and helping with a research project as strong motivating factors for crowdsourcing participants (Dunn et al., 2012). In addition, our industrial partner will incentivize participants with product vouchers for their platform 5.

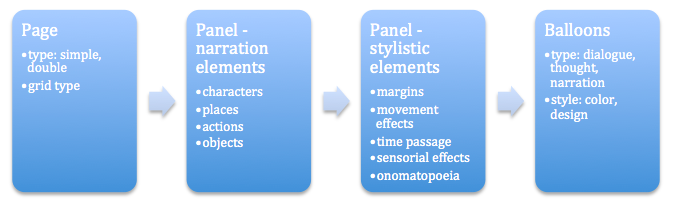

The tasks we propose are organized around a set of questions regarding a series of comics-related topics (Eisner, 1985; Ichikawa et al., 2014) on which computer algorithms are not performing well enough: complex page layouts, identification of narration elements (characters, places, events, objects), stylistic elements (balloon shapes, onomatopoeia, movement lines).

We aggregate the answers (Feng et al., 2014; Snow et al., 2008) taking into account the reliability of an annotator in a given context (task difficulty, user experience with the task, type of question) and the agreement between the annotators (Nowak et al., 2010). A quality score is thus generated for each annotation, with the best of them being selected as solutions.

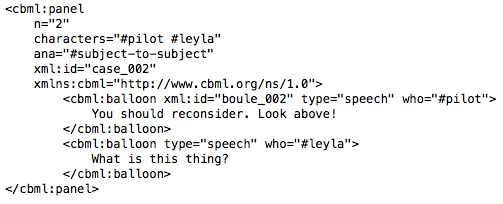

We subsequently are able to generate the ComicsML encodings (Walsh, 2012). This XML derived format is particularly useful since it’s based on the already widespread Text Encoding Initiative (TEI), allowing for declarations of page structure and composition, panels, characters, text (in all the varieties hosted by the comics medium: different types of balloons, diegetic text, onomatopoeia), events and even panel-to-panel transitions.

3.1. Page structure

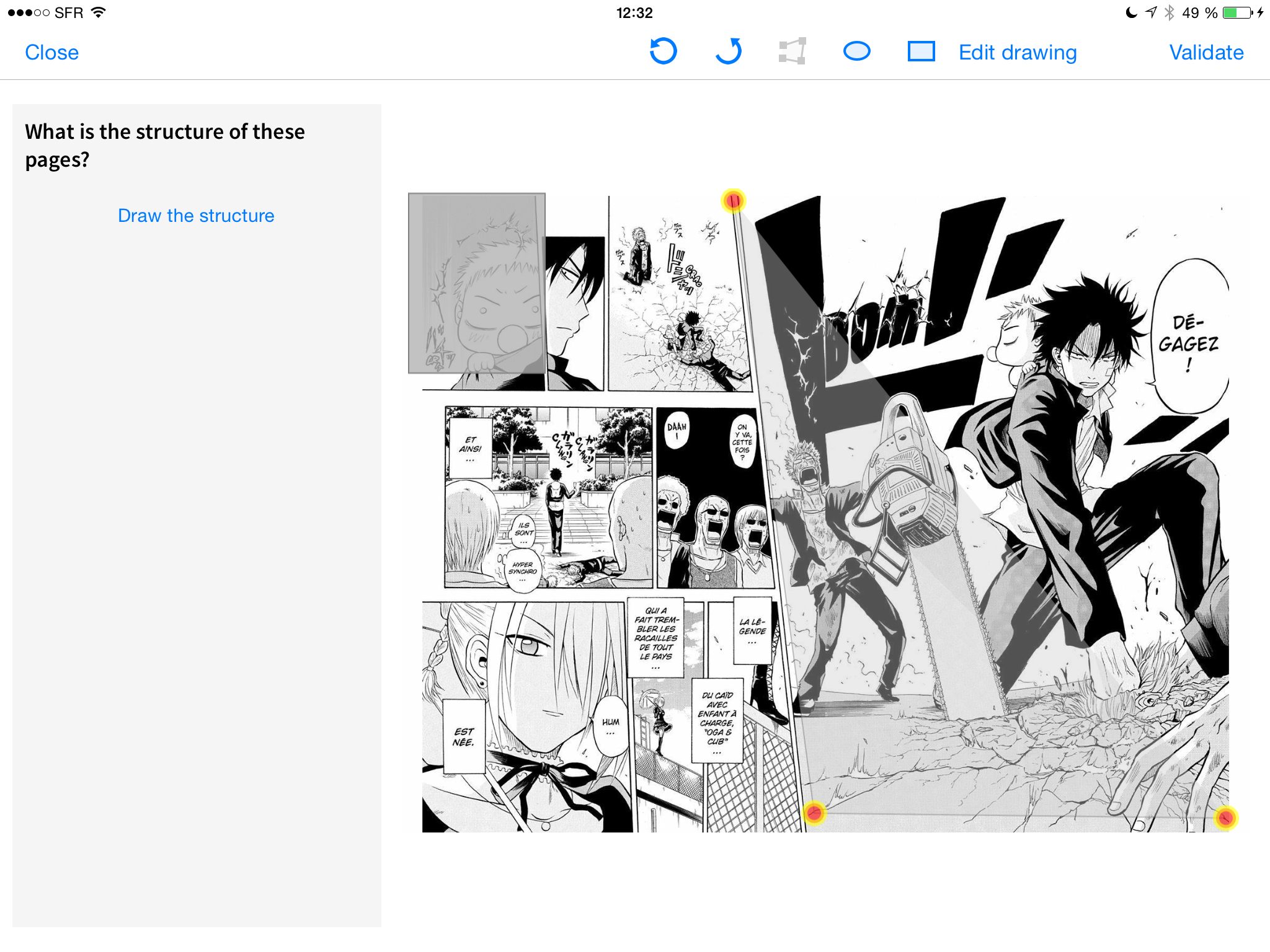

The annotators are presented with a simple interface (Fig. 2) in which they will have to make a choice between a set of suggested grid layouts. These layouts are the output of applying the automatic frame extraction algorithm developed by (Rigaud et al., 2011). Alternatively, for complex page layouts, they will be asked to draw the page layout themselves.

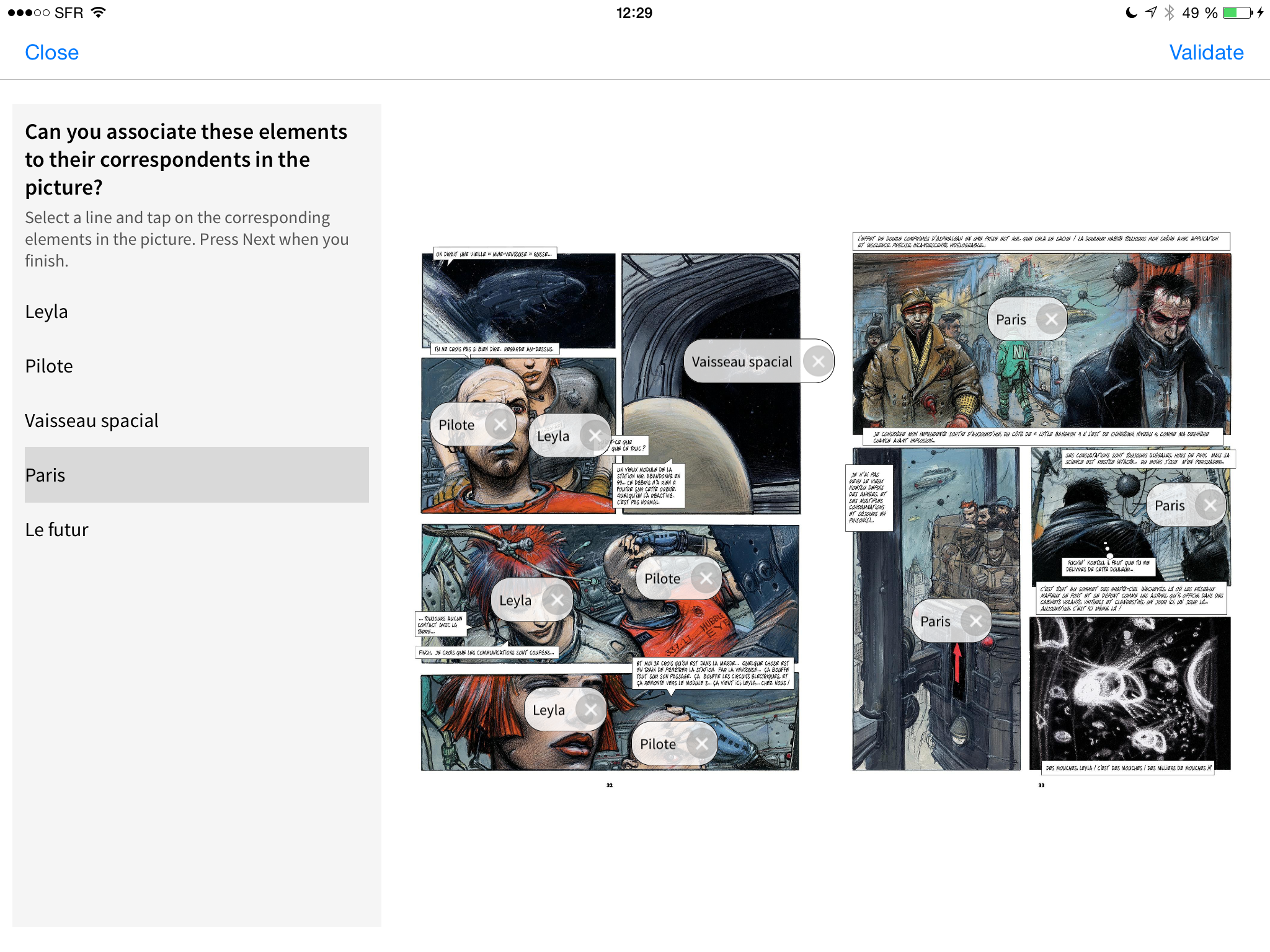

3.2. Character identification

At this step, we ask the “crowd” to simply enumerate all the characters they can identify in the current page. Characters are identified by reading their names in the text, recognising them from experience or simply giving a general statement about the character (e.g., “ masked man” may be referring to Batman). Using state of the art symbolic learning algorithms we fusion generic and specific information (e.g. if Batman and “masked man” both have high quality scores in the same context, they will both denote the same concept and will be considered as valid annotations).

3.3. Places identification

We ask the annotators to simply enumerate all the places they can recognise on the current page. We are particularly looking for named places (e.g., Gotham City, NY, planet Mars), but will also ask the annotator to mark any generic place that he might consider important for the scenes in the page (e.g., “ the interior of a bank“ [in case of a robbery], “inside a space ship” [in case of a battle in space]). These are exactly the kind of very specific annotation tasks for which state of the art image recognition algorithms are expected to fail.

3.4. Events identification

This is yet another highly specific recognition task. Annotators are asked to describe the most important events occurring in the page. The solutions generated at this step, together with the annotations obtained in the previous steps will be used to further build the ComicsML encoding of the page.

Comics scholar Scott McCloud stresses the role of ellipsis (“the blood in the gutters“ – the space between two panels) as an artistic mean for authors to engage their readers, and describes a typology of these transition spaces (McCloud, 1993). ComicsML allows us to declare such transitions through the #ana attribute of the cbml:panel element, giving us the possibility to investigate their use and their distribution across different cultural spaces (France/Belgium, Japan/Korea, USA).

3.5. Non-visual cues

Comics are a special medium, making use of the visual to depict all other non-visual senses, with the help of different drawing “tricks”, such as:

- Smoke coming out of a cigarette may engage the reader’s smelling sense

- Onomatopoeia form a particular language of their own; comics and especially manga authors have proven great creativity when it comes to expressing different sounds via stylised text (e.g., “ POW!” – punch, “ BAM!” – gunshot)

- Horizontal lines around a car suggest the car is moving at high speed, while around a ball, they express the ball’s movement

Researchers could study, for instance, the drawing style of an author and his use of non-visual cues, and go as far as creating onomatopoeia dictionaries for comics (to our knowledge, such dictionaries already exist for manga, but not for American nor European comics).

At the end of this stage, we should be able to generate a reasonably complete ComicsML encoding of the current page (see Fig. 3).

4. Conclusions

We have presented the outline of our crowdsourced annotation system for comics, as well as details of how we have designed our tasks, having in mind three main aspects: the limits of current digital comic book formats, the specifications behind the ComicsML metadata schema and theoretical principles of comics as a medium (Eisner, 1985). Last, we have presented the way in which the collected results are merged into the final ComicsML encoding and have briefly discussed some potential applications.

- Azavea, SciStarter. (2014). Citizen Science Data Factory, Part 1: Data Collection Platform Evaluation.

- Dunn, S. and Hedges, M. (2012). Engaging the Crowd with Humanities Research. Crowd-Sourcing Scoping Study. Centre for e-Research, Dept. of Digital Humanities – King’s College, London.

- Conboy, G., Duga, B., Gardeur, H., Kanai, T., Kopp, M., Kroupa, B., Lester, J., Garrish, M., Murata, M. and O’Connor E. (2014). EPUB Region Based Navigation 1.0. http://www.idpf.org/epub/renditions/region-nav/ (accessed 5 March 2016).

- Eisner, W. (1985). Comics and Sequential Art: Principles and Practices From the Legendary Cartoonist. Norton&Company, USA&U.K.

- Feng, D., Sveva, B. and Zajac, R. (2009). Acquiring High Quality Non-Expert Knowledge from On-demand Workforce. People’s Web Meets NLP-2009, ACL (2009), 51-56.

- Ichikawa, D., Kasdorf, B, Kopp, M. and Kroupa, B. (2014). EPUB Region Based Navigation Markup Guide 1.0. http://www.idpf.org/epub/guides/region-nav-markup/ (accessed 5 March 2016).

- McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding Comics – The Invisible Art, Harper Collins, USA.

- Nowak, S. and Ruger, S. (2010) How reliable are annotations via crowdsourcing? A study about inter-annotator agreement for multi-label image annotation. In Proc. MIR-2010, ACM, 557-566.

- Rigaud, C., Tsopze, N., Burie, J.-C. and Ogier, J.-M. (2011). Robust text and frame extraction from comic books. GREC-2011, Springer, 129-138.

- Sharma, A. (2010). Crowdsourcing Critical Success Factor Model: Strategies to harness the collective intelligence of the crowd. Working paper.

- Snow, R., O’Connor, B., Jurafsky, D. and Ng, A.Y. (2008). Cheap and Fast – But is it Good? Evaluating Non-Expert Annotations for Natural Language Tasks. EMNLP-2008, ACM, 254-263.

- Walsh, J.A. (2012). Comic Book Markup Language: an Introduction and Rationale. DHQ-6, 1. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/6/1/000117/000117.html (accessed 5 March 2016).

http://www.comics.org/

http://comicbookdb.com/

http://digitalcomicmuseum.com/

http://www.citebd.org/

Actialuna – Sequencity: https://www.sequencity.com